Learning from Akihabara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 5 Day Tokyo Itinerary

What To Do In Tokyo - A 5 Day Tokyo Itinerary by NERD NOMADS NerdNomads.com Tokyo has been on our bucket list for many years, and when we nally booked tickets to Japan we planned to stay ve days in Tokyo thinking this would be more than enough. But we fell head over heels in love with this metropolitan city, and ended up spending weeks exploring this strange and fascinating place! Tokyo has it all – all sorts of excellent and corky museums, grand temples, atmospheric shrines and lovely zen gardens. It is a city lled with Japanese history, but also modern, futuristic neo sci- streetscapes that make you feel like you’re a part of the Blade Runner movie. Tokyo’s 38 million inhabitants are equally proud of its ancient history and culture, as they are of its ultra-modern technology and architecture. Tokyo has a neighborhood for everyone, and it sure has something for you. Here we have put together a ve-day Tokyo itinerary with all the best things to do in Tokyo. If you don’t have ve days, then feel free to cherry pick your favorite days and things to see and do, and create your own two or three day Tokyo itinerary. Here is our five day Tokyo Itinerary! We hope you like it! Maria & Espen Nerdnomads.com Day 1 – Meiji-jingu Shrine, shopping and Japanese pop culture Areas: Harajuku – Omotesando – Shibuya The public train, subway, and metro systems in Tokyo are superb! They take you all over Tokyo in a blink, with a net of connected stations all over the city. -

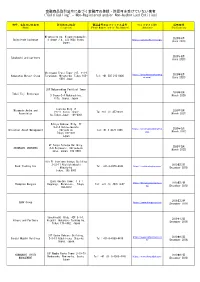

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) Miyakojima-ku, Higashinodamachi, 2020年6月 SwissTrade Exchange 4-chōme−7−4, 534-0024 Osaka, https://swisstrade.exchange/ (June 2020) Japan 2020年6月 Takahashi and partners (June 2020) Shiroyama Trust Tower 21F, 4-3-1 https://www.hamamatsumerg 2020年6月 Hamamatsu Merger Group Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105- Tel: +81 505 213 0406 er.com/ (June 2020) 0001 Japan 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. -

TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP JR Yamanote

JR Yamanote Hibiya line TOKYO TRAIN & SUBWAY MAP Ginza line Chiyoda line © Tokyo Pocket Guide Tozai line JR Takasaka Kana JR Saikyo Line Koma line Marunouchi line mecho Otsuka Sugamo gome Hanzomon line Tabata Namboku line Ikebukuro Yurakucho line Shin- Hon- Mita Line line A Otsuka Koma Nishi-Nippori Oedo line Meijiro Sengoku gome Higashi Shinjuku line Takada Zoshigaya Ikebukuro Fukutoshin line nobaba Todai Hakusan Mae JR Joban Asakusa Nippori Line Waseda Sendagi Gokokuji Nishi Myogadani Iriya Tawara Shin Waseda Nezu machi Okubo Uguisu Seibu Kagurazaka dani Inaricho JR Shinjuku Edo- Hongo Chuo gawa San- Ueno bashi Kasuga chome Naka- Line Higashi Wakamatsu Okachimachi Shinjuku Kawada Ushigome Yushima Yanagicho Korakuen Shin-Okachi Ushigome machi Kagurazaka B Shinjuku Shinjuku Ueno Hirokoji Okachimachi San-chome Akebono- Keio bashi Line Iidabashi Suehirocho Suido- Shin Gyoen- Ocha Odakyu mae Bashi Ocha nomizu JR Line Yotsuya Ichigaya no AkihabaraSobu Sanchome mizu Line Sendagaya Kodemmacho Yoyogi Yotsuya Kojimachi Kudanshita Shinano- Ogawa machi Ogawa Kanda Hanzomon Jinbucho machi Kokuritsu Ningyo Kita Awajicho -cho Sando Kyogijo Naga Takebashi tacho Mitsu koshi Harajuku Mae Aoyama Imperial Otemachi C Meiji- Itchome Kokkai Jingumae Akasaka Gijido Palace Nihonbashi mae Inoka- Mitsuke Sakura Kaya Niju- bacho shira Gaien damon bashi bacho Tameike mae Tokyo Line mae Sanno Akasaka Kasumi Shibuya Hibiya gaseki Kyobashi Roppongi Yurakucho Omotesando Nogizaka Ichome Daikan Toranomon Takaracho yama Uchi- saiwai- Hachi Ebisu Hiroo Roppongi Kamiyacho -

Tokyo Sightseeing Route

Mitsubishi UUenoeno ZZoooo Naationaltional Muuseumseum ooff B1B1 R1R1 Marunouchiarunouchi Bldg. Weesternstern Arrtt Mitsubishiitsubishi Buildinguilding B1B1 R1R1 Marunouchi Assakusaakusa Bldg. Gyoko St. Gyoko R4R4 Haanakawadonakawado Tokyo station, a 6-minute walk from the bus Weekends and holidays only Sky Hop Bus stop, is a terminal station with a rich history KITTE of more than 100 years. The “Marunouchi R2R2 Uenoeno Stationtation Seenso-jinso-ji Ekisha” has been designated an Important ● Marunouchi South Exit Cultural Property, and was restored to its UenoUeno Sta.Sta. JR Tokyo Sta. Tokyo Sightseeing original grandeur in 2012. Kaaminarimonminarimon NakamiseSt. AASAHISAHI BBEEREER R3R3 TTOKYOOKYO SSKYTREEKYTREE Sttationation Ueenono Ammeyokoeyoko R2R2 Uenoeno Stationtation JR R2R2 Heeadad Ofccee Weekends and holidays only Ueno Sta. Route Map Showa St. R5R5 Ueenono MMatsuzakayaatsuzakaya There are many attractions at Ueno Park, ● Exit 8 *It is not a HOP BUS (Open deck Bus). including the Tokyo National Museum, as Yuushimashima Teenmangunmangu The shuttle bus services are available for the Sky Hop Bus ticket. well as the National Museum of Western Art. OkachimachiOkachimachi SSta.ta. Nearby is also the popular Yanesen area. It’s Akkihabaraihabara a great spot to walk around old streets while trying out various snacks. Marui Sooccerccer Muuseumseum Exit 4 ● R6R6 (Suuehirochoehirocho) Sumida River Ouurr Shhuttleuttle Buuss Seervicervice HibiyaLine Sta. Ueno Weekday 10:00-20:00 A Marunouchiarunouchi Shuttlehuttle Weekend/Holiday 8:00-20:00 ↑Mukojima R3R3 TOKYOTOKYO SSKYTREEKYTREE TOKYO SKYTREE Sta. Edo St. 4 Front Exit ● Metropolitan Expressway Stationtation TOKYO SKYTREE Kaandanda Shhrinerine 5 Akkihabaraihabara At Solamachi, which also serves as TOKYO Town Asakusa/TOKYO SKYTREE Course 1010 9 8 7 6 SKYTREE’s entrance, you can go shopping R3R3 1111 on the first floor’s Japanese-style “Station RedRed (1 trip 90 min./every 35 min.) Imperial coursecourse Theater Street.” Also don’t miss the fourth floor Weekday Asakusa St. -

Keeping up with the Kimono Time(PDF:234KB)

CULTURE such as kabuki, shamisen (a traditional The casual styling of a kimono from the tailor where Hiramatsu works, with undershirt and hat. Japanese stringed instrument) and rakugo Keeping Up with the (a traditional Japanese art of storytelling). Around that time, she explains, there was a boom in vintage shops and she found Kimono Time herself quickly collecting a variety of dif- Meet two innovative people inspiring fresh ways to ferent kimono of various colors, patterns, accessorize and wear the traditional garment of Japan as and fabrics. Using her skill as an illustra- part of a modern wardrobe. tor and combining her love of manga and pop culture, she began creating drawings by Anne Lucas that show how to wear and accessorize kimono in a more edgy or kawaii (cute) veryone says, “Tokyo has changed.” In many ways, it has. But in an equal fashion. She gathered the illustrations and E number of ways, it has retained its intrinsic traditions and culture. This knowledge into a book called Kimono Bancho, and people started calling her feeling of old meets new is evident in all aspects of life here, including in the kimono bancho. realms of cuisine, architecture, business, and fashion. Hiramatsu, by contrast, has been working his way up within a tra- Perhaps one of the most obvious and quintessentially Japanese examples ditional Japanese company that has been tailor-making kimonos for of how the city—and the country, no less—has kept its essence alive is in the over 100 years. While the main clientele of the tailor has historically fact that we still see kimono on the streets, not to mention on the catwalks. -

ACSF-16-01 16Th ACSF Informal Meeting

Informal Document - ACSF-16-01 16th ACSF Informal meeting Informal meeting Date: January 23rd – 25th, 2018 Tuesday 23 January, 2018 starting at 14:00 until Thursday 25 January, 2018 ending at 15:00 Welcome Reception Date: January 23rd, 2018 Venue: AP Ichigaya Address: 1-10 Goban-cho Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo Japan Caution!! This meeting room is different from JASIC office! Registration Please send the following information to; M r. Jochen Schaefer ([email protected]) and Mr. Yoshihisa Tsuburai ([email protected]) no later than 10th January, 2018. ※In the case, we have more than 50 registrations, we have to limit the participation to delegates, which have participated in the previous sessions on a regular basis. 1) your name 2) your title and name of your business 3) your e-mail address 4) your arrival and departure date if you don’t participate in a full schedule. 5) your participation for the Welcome Reception on January 23rd. AP Ichigaya Address: 1-10 Goban-cho Chiyoda-ku, MAP Tokyo Japan Google map; Tel:+81-(0)3-3511-3109 https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=13lqQh_nJ5AhEGCLwA : 6BQGvllnOE&hl=en_US&ll=35.69069912272502%2C139.73579670300 Fax +81-(0)3-3511-7109 637&z=18 Arcadia Ichigaya Ichigaya station (Underground) Ichigaya Mitsuke JR Police station Ichigaya Nihon University station Exit 3 Exit 2 Mizuo bank AP Ichigaya Access from the airports AP Ichigaya From Narita Airport to AP Ichigaya 80-120 mins by Airport Limousine Bus to Shinjuku. Limousine Bus service to Shinjuku is available every hour. https://www.limousinebus.co.jp/en/bus_services/narita/shinjuku.html From Shinjuku, take JR Sobu Line(yellow above) for Ichigaya. -

Best of Tokyo and Beyond 8 Days/7 Nights Best of Tokyo and Beyond

Best of Tokyo and Beyond 8 Days/7 Nights Best of Tokyo and Beyond Tour Overview Experience more of one of world's greatest cities on the Best of Tokyo and Beyond tour. To the uninitiated, Tokyo may seem like a whirlwind of people and traffic. Yet, behind the ordered chaos lie remnants of a very different past. You could easily spend a lifetime exploring Tokyo and never run out of places and things to discover. Destinations Tokyo, Hakone, Kamakura Tour Factors Cultural Immersion Pace Physical Activity Tour Details From “funky” old Ueno and nearby Yanaka with its fine park, museums, and old houses, to the ultra-modern Ginza with its endless department stores … the sheer energy level of Tokyo will sweep you away. And by night, Tokyo really comes into its own. Mazes of blazing neon fill every available nook and cranny of the city’s streets and alleys. Above all, Tokyo is not just a destination, but an experience. You will learn the ancient religious traditions of the Japanese, visit the famous “Daibutsu” in Kamakura, explore Tokyo’s largest Shinto Shrine dedicated to the emperor who began the modernization of Japan and see the icon of Japan, Mt. Fuji (weather-permitting). Combine this tour with the Best of Kyoto and Beyond tour for a more complete Japanese experience. Or, if you only want to spend a few days in Kyoto either before or after the tour, we can arrange this for you. Contact us for details. Akihabara District and Maid Cafe Harajuku District and Takeshita Dori Tour Highlights Meiji Shrine and Omotesando Ginza District Asakusa - Sensoji Temple and Asakusa Shrine Hakone - Hakone Ropeway, Owakudani and Lake Ashi Sightseeing Boats Kamakura - Kotokuin (Great Buddha) and Hokokuji (Bamboo Temple) including Tea and Sweets in the Bamboo Garden Travel Guard Gold Policy (for American tour members only) Tour Inclusions Electronic version of Tour Handbook and Japanese History International airfare is NOT included. -

Tokyo, So Here Are the Top 100 Favourite Places to Visit and Things to Do in Tokyo

Dive into the flickering neon light of Akihabara, practice tree bathing in Harajuku or live the 50s life in Shinjuku and Shibamata. There are plenty of ideas for a first time visit to Tokyo, So here are the top 100 favourite places to visit and things to do in Tokyo. □ Shibuya Crossing □ Sensō-ji □ Takeshita Street □ Chidorigafuchi Boat □ Ueno Park □ Skytree □ Meiji Shrine □ Tokyo Metropolitan Government □ Robot Restaurant □ Capsule hotel □ Shibamata □ Imperial Palace □ Yanaka Ginza □ Cat Street □ Tokyo Tower □ Takarazuka Revue □ Roppongi Hills □ Todoroki Valley Park □ Ninja Restaurant □ Rainbow Bridge www.travelonthebrain.net □ Kabukiza Theatre □ Ghibli Museum □ Sumo Wrestling □ Book And Bed Tokyo Asakusa □ Day trip to Fuji □ Izakayas in Shinjuku □ Tsukiji □ Mario Go Kart □ Dinner Boat Tour □ Samurai Museum □ Tokyo Disneyland / DisneySea □ Japanese Cooking Class □ Sanja Matsuri □ Samuai Training □ Hello Kitty Puroland □ Ooedo Onsen □ Nakano Broadway □ Pokémon Center □ Anime Japan □ Alice in Wonderland Café □ Calligraphy Lesson □ Edo Tokyo Open Air Museum □ Cat Temple □ Sake Brewery Tour □ Rickshaw Tour □ Wear a kimono □ Daiso □ Harajuku Street Style □ Manga & Anime in Akihabara □ Shinjuku Gyoen □ Maid Café □ Baseball Game □ Tea Ceremony □ Tokyo Station □ Yoyogi Park □ Nezu Museum □ 8Bit Café □ Meguro River □ Odaiba Seaside Park □ Anata no Warehouse □ Bike Tour □ The Yagiri no Watashi □ Nihonbashi/Edo Bridge □ Kawaii Monster Café □ Kameida Tenjin Shrine □ Karaoke □ Eat Blue Ramen □ Shibuya 109 □ Moomin House Café □ Nippori Train Watching -

Meiji Shrine 33 Harajuku Southern Tokyo

NORTHERN TOKYO CONTENTS DESTINATIONS EASTERN TOKYO SENSOJI TEMPLE SOUTHERN TOKYO WESTERN TOKYO 北部の東京 NORTHERN TOKYO SENSOJI TEMPLE SENSOJI TEMPLE SENSOJI TEMPLE SENSOJI TEMPLE SENSOJI TEMPLE NORTHERN TOKYO CONTENTS WHEN PEOPLE THINK OF TOKYO THEY THINK OF A MEGALOPOLIS TOKYO, JAPAN OF MODERN SKYSCRAPERS. THAT’S A PRETTY ACCURATE DE- CITY TRAVEL GUIDE SCRIPTION OF MOST OF TOKYO. THE EXCEPTION TO THIS ARE THE NORTHERN NEIGHBORHOODS OF ASAKUSA AND UENO. VOL. 13 JUNE 2017 02 $8.99 DESTINATIONS EASTERN TOKYO 05 SENSOJI TEMPLE EASTERN TOKYO IS LARGELY RESIDENTIAL AND INDUSTRIAL. MOST 07 TOKYO SKYTREE SIGHTS ARE CONCENTRATED IN THE SUMIDA NEIGHBORHOOD 09 EDO-MUSEUM SUCH AS TOKYO’S MAIN SUMO STADIUM RYOGOKU KOKUGIKAN. 13 AKIHABARA 15 TSUKIJI MARKET 17 KOISHIKAWA 21 TOKYO TOWER 23 ODAIBA 25 ROPPONGI HILLS 10 29 SHIBUYA 31 MEIJI SHRINE 33 HARAJUKU SOUTHERN TOKYO WITH ITS NUMEROUS SKYSCRAPERS AND DEPARTMENT STORES, SOUTHERN TOKYO IS ONE OF THE CITY’S HIPPER AREAS. THIS YOUNGER DISTRICT IS HOME TO THE LATEST FASHION, ENTER- 18 TAINMENT, FOOD AND TRENDS IN JAPAN. WESTERN TOKYO WESTERN TOKYO IS THE MOST POPULATED AREA, MOST ACTIVELY CHANGING, AND THE MOST VIBRANT AND STYLISH AREA IN TOKYO. IT IS THE DEFINITION OF THE CITY THAT NEVER SLEEPS. 26 A JOURNEY THROUGH THE FOUR MAJOR REGIONS の 考 超 東 地 例 え 高 京 域 外 て 層 を 北方 で は、い ビ 考 す。浅 ま ル え 草 す。の る と メ 人 上 ガ は、 野 ポ 近 の リ 代 北 ス 的 部 を な WHEN PEOPLE THINK OF TOKYO THEY THINK OF A MEGALOPOLIS OF MODERN SKYSCRAPERS. -

Tours 1, Tokyo Morning 2, Cityrama Tokyo Morning 3, Tokyo Afternoon

TOURS 1, TOKYO MORNING Tokyo Tower Enjoy a panoramic view of Tokyo from its main observatory. Imperial Palace Plaza Short photo stop at the outer garden of the Palace. Akihabara and Ueno(Drive through) Akihabara Electric appliances and computers discount shopping center. Ueno Noted for its park and market area "Ameyoko" for bargain shopping. Asakusa Kannon Temple and Nakamise Shopping Street The oldest and most popular temple in Tokyo. A promenade section called Nakamise-dori is basically both sides of narrow, paved entranceway to the temple crammed with tiny food and souvenir shops. Ginza Shopping District(Drive through) The most celebrated shopping and amusement area. Tasaki Pearl Gallery See the process of pearl cultivation. One lucky participant will be presented with a pearl. Tour disbands on arrival at the Tasaki Pearl Gallery. Sending service to hotels and other designated places are offered by Tasaki Pearl Gallery. 2, CITYRAMA TOKYO MORNING Meiji Shinto Shrine Japan's most famous Shinto shrine dedicated to the Emperor Meiji and his consort. Akasaka Guest House(Drive by) Former Akasaka Palace, now used as a state guest house for visiting dignitaries. National Diet Building (Drive by) The Japanese Capitol (the House of Parliament). Imperial Palace East Garden This is where you'll find what's left of the central keep of old Edo Castle (the stone foundation). Take a stroll in one of the vast inner gardens of the Imperial Palace. (on Mon. and Fri. when the garden is closed ,visit the Imperial Palace Plaza instead) Asakusa Kannon Temple and Nakamise Shopping Street The oldest and most popular temple in Tokyo. -

Past & Present of Japan & Thailand

12 Days/11 Nights Departs Daily from the US Avanti Journeys - Past & Present of Japan & Thailand: Tokyo, Kyoto, Bangkok, & Chiang Mai Time travel into the past to learn the history and ancient customs of these two venerable countries with their countless shrines, revered Buddhist culture, and honored traditions. Conversely, you'll encounter today's Japan; the land of high-tech, bullet trains and Michelin starred restaurants. Then experience the bustling and high-energy of Bangkok, while Chiang Mai presents an alluring alternative; blissfully calm amid beautiful temples and misty mountains. ACCOMMODATIONS • 3 Nights Tokyo • 3 Nights Bangkok • 3 Nights Kyoto • 2 Nights Chiang Mai INCLUSIONS • Private Arrival & Departure • Private Bangkok Tour by Train, • Air LAX to Tokyo, Transfers per City Boat, Foot, & Tuk Tuk Tokyo to Bangkok, • Private Future is Tokyo via • Private Old Chiang Mai Bangkok to Chiang Mai, Public Transportation City Walking Tour Chiang Mai to Bangkok, • Private Pop Culture Afternoon • Private Royal Park Rajapurek Bangkok to LAX* Tour via Public Transportation & Wat Doi Khom Temple Tour • Daily Breakfast • Private Classic Kyoto Tour via • Siam Niramit Show Public Transportation with Private Transfers • Private Kyoto Home Visit with • Roundtrip Green-Class Rail Tea Ceremony with Kimono between Tokyo & Kyoto Wearing Experience via Taxi plus Seat Reservations ARRIVAL: Arriving at Haneda or Narita Airport, meet your English-speaking driver for your private transfer to your hotel. The remainder of the day is at your leisure for relaxation or exploring. Dinner will be on your own this evening. Greetings are important in Japan, where the culture is defined by politeness and formality. -

Welcome to Japan ! Japan Is One of the Most Popular Travel Destinations in the World

Welcome to Japan ! Japan is one of the most popular travel destinations in the world. November is one of the best time to visit Japan, as the weather is relatively dry and mild, and the autumn colors are spectacular in many parts of the country. You can enjoy sightseeing, Japanese culture, shopping and so on. Spot to enjoy within 30 minutes from the symposium venue! Ramen Tsukiji market & Tsukiji Outer market,“SUSHI” “Chukamen” noodles, which Tsukiji market and the Tsukiji outer market is came to Japan from China, have Japan’s leading seafood wholesale market. Food flowered in Japan as a unique You can encounter all of Japan’s traditional Japanese food culture. You can foods such as“SUSHI”. There are also retail enjoy soup, noodles and a variety shops along with numerous restaurants. Japanese of taste stuck to the topping. new culinary trends are born here. Access ▼ 15 minutes subway ride from the Tokyo International Tokyo Ramen Street Forum This is located in the“First Avenue Tokyo Station”, at the Yaesu side of Tokyo Station. This street has eight famous Tokyo ramen shops. ラ ー メ ン 寿 司 築 地 Access ▼ 15 minutes walk from the Tokyo International Forum Ginza & Marunouchi Nakadori Akihabara Ginza & Marunouchi Nakadori Akihabara Electric Town is representative place are one of the top brand-oriented of anime and games, cosplay, idle, etc. This town Shopping streets in Tokyo, which connects has a unique personality. Not only shopping, but Otemachi station and Yurakucho you can enjoy the Japanese pop culture. station. Gathered in the new and Access ▼ 6 minutes JR Line ride from the Yurakucho Station old buildings are various shops and restaurants, from old established shops to new outlets.