Elaeagnus Pungens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SALT TOLERANT PLANTS Recommended for Pender County Landscapes

North Carolina Cooperative Extension NC STATE UNIVERSITY SALT TOLERANT PLANTS Recommended for Pender County Landscapes Pender County Cooperative Extension Urban Horticulture Leaflet 14 Coastal Challenges Plants growing at the beach are subjected to environmental conditions much different than those planted further inland. Factors such as blowing sand, poor soils, high temperatures, and excessive drainage all influence how well plants perform in coastal landscapes, though the most significant effect on growth is salt spray. Most plants will not tolerate salt accumulating on their foliage, making plant selection for beachfront land- scapes particularly challenging. Salt Spray Salt spray is created when waves break on the beach, throwing tiny droplets of salty water into the air. On-shore breezes blow this salt laden air landward where it comes in contact with plant foliage. The amount of salt spray plants receive varies depending on their proximity to the beachfront, creating different vegetation zones as one gets further away from the beachfront. The most salt-tolerant species surviving in the frontal dune area. As distance away from the ocean increases, the level of salt spray decreases, allowing plants with less salt tolerance to survive. Natural Protection The impact of salt spray on plants can be lessened by physically blocking salt laden winds. This occurs naturally in the maritime forest, where beachfront plants protect landward species by creating a layer of foliage that blocks salt spray. It is easy to see this effect on the ocean side of maritime forest plants, which are “sheared” by salt spray, causing them to grow at a slant away from the oceanfront. -

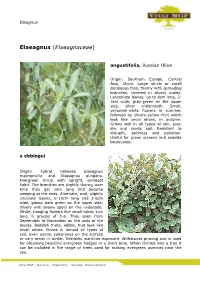

Elaeagnus (Elaeagnaceae)

Eleagnus Elaeagnus (Elaeagnaceae) angustifolia, Russian Olive Origin: Southern Europe, Central Asia, China. Large shrub or small deciduous tree, thorny with spreading branches, covered in silvery scales. Lanceolate leaves, up to 8cm long, 2- 3cm wide, grey-green on the upper side, silver underneath. Small, yellowish-white flowers in summer, followed by silvery-yellow fruit which look like small olives, in autumn. Grows well in all types of soil, even dry and sandy soil. Resistant to drought, saltiness and pollution. Useful for green screens and seaside boulevards. x ebbingei Origin: hybrid between Elaeagnus macrophylla and Elaeagnus pungens. Evergreen shrub with upright, compact habit. The branches are slightly thorny, over time they get very long and become weeping at the ends. Alternate, oval, slightly undulate leaves, 5-10cm long and 3-6cm wide, glossy dark green on the upper side, silvery with brown spots on the underside. White, hanging flowers like small tubes 1cm long in groups of 3-6. They open from September to November on the axils of the leaves. Reddish fruits, edible, that look like small olives. Grows in almost all types of soil, even sandy, calcareous on the surface or very moist in winter. Tolerates maritime exposure. Withstands pruning and is used for obtaining beautiful evergreen hedges in a short time. When formed into a tree it can be included in the range of trees used for making evergreen avenues near the sea. Vivai MGF – Nursery – Pépinières – Viveros - Baumschulen Eleagnus x ebbingei “Eleador”® Origin: France. Selection of Elaeagnus x ebbingei “Limelight”, from which it differs in the following ways: • in the first years it grows more in width and less in height; • the leaves are larger (7-12cm long, 4-6cm wide), and the central golden yellow mark is wider and reaches the margins; • it does not produce branches with all green leaves, but only an occasional branch which bears both variegated leaves and green leaves. -

Non-Native Invasive Plants of the City of Alexandria, Virginia

March 1, 2019 Non-Native Invasive Plants of the City of Alexandria, Virginia Non-native invasive plants have increasingly become a major threat to natural areas, parks, forests, and wetlands by displacing native species and wildlife and significantly degrading habitats. Today, they are considered the greatest threat to natural areas and global biodiversity, second only to habitat loss resulting from development and urbanization (Vitousek et al. 1996, Pimentel et al. 2005). The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation has identified 90 non-native invasive plants that threaten natural areas and lands in Virginia (Heffernan et al. 2014) and Swearingen et al. (2010) include 80 plants from a list of nearly 280 non-native invasive plant species documented within the mid- Atlantic region. Largely overlapping with these and other regional lists are 116 species that were documented in the City of Alexandria, Virginia during vegetation surveys and natural resource assessments by the City of Alexandria Dept. of Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities (RPCA), Natural Lands Management Section. This list is not regulatory but serves as an educational reference informing those with concerns about non-native invasive plants in the City of Alexandria and vicinity, including taking action to prevent the further spread of these species by not planting them. Exotic species are those that are not native to a particular place or habitat as a result of human intervention. A non-native invasive plant is here defined as one that exhibits some degree of invasiveness, whether dominant and widespread in a particular habitat or landscape or much less common but long-lived and extremely persistent in places where it occurs. -

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 ON THE COVER Duck potato (Sagittaria latifolia) at Ocmulgee National Monument. Photograph by: Sarah C. Heath, SECN Botanist. Vegetation Community Monitoring at Ocmulgee National Monument, 2011 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2014/702 Sarah Corbett Heath1 Michael W. Byrne2 1USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Cumberland Island National Seashore 101 Wheeler Street Saint Marys, Georgia 31558 2USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network 135 Phoenix Road Athens, Georgia 30605 September 2014 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

Broadleaf Evergreen

SHRUBS Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia • Size: medium shrub (5’ tall by 5’ wide); often wild sprays of stems • Flowers: May to fall; white/pink tubular flowers • Fruit: not significant • Fall Color: broadleaf evergreen; sometimes winter foliage is a deep maroon • Culture: full sun; adaptable to most soils; tough • Disease/Insect: none significant • Use: foundations, masses • Cultivars: many including ‘Sherwood’, Confetti™, Sunrise™ (‘Edward Goucher’ is a hybrid) flowers Aucuba japonica ‘Variegata’ Gold-dust Plant Acuba japonica ‘Variegata’ Gold-dust Plant • Size: medium shrub (5’ tall by 5’ wide) • Flowers: not showy; small, purple, terminal panicles; spring • Fruit: dioecious (plant either male or female); lipstick red clusters midwinter on female plants • Fall Color: none/broadleaf evergreen • Culture: partial sun to shade; cold hardy in zones 7 and 8; locate near protection in zone 6 • Disease/Insect: none significant • Use: tropical looking broadleaf evergreen; purchase female clone • Cultivars: species has green foliage; several outstanding variegated (yellow/green) foliage cultivars; some with gold spots Berberis thunbergii var. atropurpurea Red-leaf Japanese Barberry Berberis thunbergii var. atropurpurea Redleaf Japanese Barberry • Size: small deciduous shrub (3’ tall by 3’ wide) • Flowers: small, yellow, insignificant • Fruit: red; can be attractive in winter • Fall Color: variable; can be red-orange • Culture: full sun; drought tolerant • Disease/Insect: none significant • Use: median strips, -

The Plant List

the list A Companion to the Choosing the Right Plants Natural Lawn & Garden Guide a better way to beautiful www.savingwater.org Waterwise garden by Stacie Crooks Discover a better way to beautiful! his plant list is a new companion to Choosing the The list on the following pages contains just some of the Right Plants, one of the Natural Lawn & Garden many plants that can be happy here in the temperate Pacific T Guides produced by the Saving Water Partnership Northwest, organized by several key themes. A number of (see the back panel to request your free copy). These guides these plants are Great Plant Picks ( ) selections, chosen will help you garden in balance with nature, so you can enjoy because they are vigorous and easy to grow in Northwest a beautiful yard that’s healthy, easy to maintain and good for gardens, while offering reasonable resistance to pests and the environment. diseases, as well as other attributes. (For details about the GPP program and to find additional reference materials, When choosing plants, we often think about factors refer to Resources & Credits on page 12.) like size, shape, foliage and flower color. But the most important consideration should be whether a site provides Remember, this plant list is just a starting point. The more the conditions a specific plant needs to thrive. Soil type, information you have about your garden’s conditions and drainage, sun and shade—all affect a plant’s health and, as a particular plant’s needs before you purchase a plant, the a result, its appearance and maintenance needs. -

Bioinvasion and Global Environmental Governance: the Transnational Policy Network on Invasive Alien Species China's Actions O

1 Bioinvasion and Global Environmental Governance: The Transnational Policy Network on Invasive Alien Species China’s Actions on IAS Description1 The People’s Republic of China is a communist state in East Asia, bordering the East China Sea, Korea Bay, Yellow Sea, and South China Sea, between North Korea and Vietnam. For centuries China stood as a leading civilization, outpacing the rest of the world in the arts and sciences, but in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the country was beset by civil unrest, major famines, military defeats, and foreign occupation. The claimed area of the ROC includes Mainland China and several off-shore islands (Taiwan, Outer Mongolia, Northern Burma, and Tuva, which is now Russian territory). The current President Ma Ying-jeou reinstated the ROC's claim to be the sole legitimate government of China and the claim that mainland China is part of ROC's territory. The extremely diverse climate; tropical in south to subarctic in north, varies over the diverse terrain, mostly mountains, high plateaus, deserts in west; plains, deltas, and hills in east. After 1978, Deng Xiaoping and other leaders focused on market-oriented economic development and by 2000 output had quadrupled. Economic development has been more rapid in coastal provinces than in the interior, and approximately 200 million rural laborers and their dependents have relocated to urban areas to find work. One demographic consequence of the "one child" policy is that China is now one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world. For much of the population (1.3 billion), living standards have improved dramatically and the room for personal choice has expanded, yet political controls remain tight. -

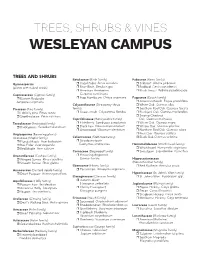

Trees, Shrubs & Vines

TREES, SHRUBS & VINES WESLEYAN CAMPUS TREES AND SHRUBS Betulaceae (Birch family) Fabaceae (Bean family) Gymnosperms r Hazel Alder Alnus serrulata r Silktree† Albizia julibrissin (plants with naked seeds) r River Birch Betula nigra r Redbud Cercis canadensis r American Hornbeam r Black Locust Robinia pseudoacacia Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Carpinus caroliniana r Eastern Redcedar r Hop-Hornbeam Ostrya virginiana Fagaceae (Beech family) Juniperus virginiana r American Beech Fagus grandifolia Calycanthaceae (Strawberry-shrub r White Oak Quercus alba Pinaceae (Pine family) family) r Southern Red Oak Quercus falcata r Loblolly pine Pinus taeda r Sweet-shrub Calycanthus floridus r Blackjack Oak Quercus marilandica r Shortleaf pine Pinus echinata r Swamp Chestnut Caprifoliaceae (Honeysuckle family) Oak Quercus michauxii Taxodiaceae (Redwood family) r Elderberry Sambucus canadensis r Water Oak Quercus nigra r Baldcypress Taxodium distichum r Black haw Viburnum prunifolium r Willow Oak Quercus phellos r Arrowwood Viburnum dentatum r Northern Red Oak Quercus rubra Angiosperms (flowering plants) r Post Oak Quercus stellata Aceraceae (Maple family) Celastraceae (Staff-tree family) r Black Oak Quercus velutina r Florida Maple Acer barbatum r Strawberry bush r Box Elder Acer negundo Euonymus americanus Hamamelidaceae (Witch hazel family) r Red Maple Acer rubrum r Witch hazel Hamamelis virginiana Cornaceae (Dogwood family) r Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Anacardiaceae (Cashew family) r Flowering dogwood r Winged Sumac Rhus copallina Cornus florida Hippocastanaceae r Smooth Sumac Rhus glabra (Horsechestnut family) Ebenaceae (Ebony family) r Red Buckeye Aesculus pavia Annonaceae (Custard Apple family) r Persimmon Diospyros virginiana r Dwarf Pawpaw Asimina parviflora Hypericaceae (St. John’s-Wort family) Elaeagnaceae (Oleaster family) r St. -

1980-04R.Pdf

COMING IN THE NEXT ISSUE Victoria Padilla is recognized as an expert on bromeliads. She will share her knowledge with readers in the OctoberlNovember issue when she writes about their history and development as popular house plants. In addition, look for George Taloumis' article on a charming Savannah townhouse garden and an article on new poinsettia varieties by another expert, Paul Ecke. Roger D. Way will write about new apple varieties and Mrs. Ralph Cannon will offer her G: hoices for hardy plants for damp soils. And last but not least, look for a staff article on money-saving ideas for the garden. We've canvassed over 100 gardeners for their best tips. All this and more in the next issue of American Horticulturist. Illustration by Vi rgini a Daley .- VOLUME 59 NUMBER 4 Judy Powell EDITO R Rebecca McClimans ART DIRECTOR Pam Geick PRODUCTION ASS ISTANT Steven H . Davis Jane Steffey ED ITO RI AL ASS ISTANTS H . Marc Cath ey Gi lbert S. Da ni els Donald Wyman H ORTICULTURAL CONSULTANTS Gil bert S. Daniels BOOK EDITOR Page 28 Page 24 May Lin Roscoe BUSINESS MA AGER Dorothy Sowerby EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS FEATURES COORDINATOR Broad-leaved Evergreens 16 Judy Canady MEMBERSH IP/SUBSCRIPTI O N Text and Photograph y by Donald Wyman SERVICE Padua 18 Ci nd y Weakland Text and Photography by David W. Lee ASS IST ANT TO THE EDITOR John Si mm ons Bulbs That Last and Last 23 PRODUCTION C OORDINATIO N Isabel Zucker Chro magraphics In c. Plant Propagation-The Future is Here 24 COLOR SEPARATI ONS Chiko Haramaki and Charles Heuser C. -

Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden, 2002. Report of a Rapid Biodiversity Assessment at Mulun National Nature Reserve, North Guangxi, China, 18 to 23 July 1998

Report of a Rapid Biodiversity Assessment at Mulun National Nature Reserve, North Guangxi, China, 18 to 23 July 1998 Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden in collaboration with Guangxi Forestry Department Guangxi Institute of Botany Guangxi Normal University South China Normal University Xinyang Teachers' College June 2002 South China Forest Biodiversity Survey Report Series: No. 13 (Online Simplified Version) Report of a Rapid Biodiversity Assessment at Mulun National Nature Reserve, North Guangxi, China, 18 to 23 July 1998 Editors John R. Fellowes, Michael W.N. Lau, Billy C.H. Hau, Ng Sai-Chit, Bosco P.L. Chan and Gloria L.P. Siu Contributors Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden: Billy C.H. Hau (BH) John R. Fellowes (JRF) Michael W.N. Lau (ML) Lee Kwok Shing (LKS) Graham T. Reels (GTR) Gloria L.P. Siu (GS) Bosco P.L. Chan (BC) Ng Sai-Chit (NSC) Guangxi Forestry Department: Qin Wengang (QWG) Tan Weining (TWN) Xu Zhihong (XZH) Guangxi Institute of Botany: Wei Fanan (WFN) Wang Yuguo (WYG) Wen Hequn (WHQ) Guangxi Normal University: Lu Liren (LLR) Xinyang Teachers’College: Li Hongjing (LHJ) South China Normal University: Lu Pingke (LPK) Voluntary consultant: Keith D.P. Wilson (KW) Background The present report details the findings of a trip to the north of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region by members of Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden (KFBG) in Hong Kong and their colleagues, as part of KFBG's South China Biodiversity Conservation Programme. The overall aim of the programme is to minimise the loss of forest biodiversity in the region, and the emphasis in the first phase is on gathering up-to-date information on the distribution and status of fauna and flora. -

A Comparison of Native Versus Old-Field Vegetation in Upland Pinelands Managed with Frequent Fire, South Georgia, Usa

A COMPARISON OF NATIVE VERSUS OLD-FIELD VEGETATION IN UPLAND PINELANDS MANAGED WITH FREQUENT FIRE, SOUTH GEORGIA, USA Thomas E. Ostertag1 and Kevin M. Robertson2 Tall Timbers Research Station, 13093 Henry Beadel Drive, Tallahassee, FL 32312, USA ABSTRACT Fire-maintained, herb-dominated upland pinelands of the southeastern U.S. Coastal Plain may be broadly divided into those that have arisen through secondary succession following abandonment of agriculture (old-field pinelands) and those that have never been plowed (native pinelands). The ability to distinguish these habitat types is important for setting conservation priorities by identifying natural areas for conservation and appropriate management and for assessing the ecological value and restoration potential for old-field pine forests managed with frequent fire. However, differences in species composition have rarely been quantified. The goals of this study were to characterize the species composition of native and old-field pineland ground cover, test the ability to distinguish communities of previously unknown disturbance history, and suggest indicator species for native versus old-field pinelands. Plant composition was surveyed in areas known to be native ground cover, those known to be old fields, and those with an uncertain disturbance history. Twelve permanent plots were established in each cover type and sampled in spring (April–May) and fall (October–November) in 2004 and 2005. Of the 232 species identified in the plots, 56 species were present only in native ground-cover plots, of which 17 species occurred in a sufficient number of plots to have a statistically significant binomial probability of occurring in native ground cover and might be considered indicator species. -

Cold Injury in the Landscape: Georgia, 1983-841

Michael A. Dirr ORNAMENTALS Sept.-Oct. 1988 Horticulture Dept., University of Georgia, NORTHWEST Vol. 2, Issue 5 and ARCHIVES Pages 5-9 Gerald Smith Ext. Horticulturist, University of Georgia COLD INJURY IN THE LANDSCAPE: GEORGIA, 1983-841 This past winter (1983-1984) proved extremely harsh on landscape plants, especially broadleaf evergreens. Temperatures in Athens were mild in November with only one day below 32°F (30°F). In December, only five days of below zero temperatures (31, 27, 31, 30, 30) preceded the records lows of 7, 3, and 9°F on December 24, 25, and 26, respectively. A few hours of exposure to low temperatures are not as severe as prolonged exposure. Plants did not fully acclimate this fall because of the mild temperatures preceding the "freeze." Cold acclimation occurs in two stages. The first is triggered by short days; the second by repeated exposure to low temperatures. Maximum plant hardiness is usually attained by January and obviously many plants were simply not "ready" in December for the cold. The low temperatures coupled with the drying winds produced ideal conditions for injury. Succulent growth, especially that resulting from high fertilization, is more susceptible to cold damage. The tissue simply never hardens. Container-grown nursery stock heavily fertilized in the fall was noted to be more severely injured. This coupled with the fact that the root systems are not protected makes container stock prone to tremendous injury. Considerable research has shown that roots are much more cold sensitive than above ground plant parts. For example, boxwood or Japanese holly roots (white root tips) are killed at about 20 to 25°F while the tops are hardy to -5 to -10°F.