Imdb.Com Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday, September 5, 2021, WDHS Family Update

Sunday, September 5, 2021, WDHS Family Update Hello Everyone, Happy Labor Day Weekend! After the rain on Friday and Saturday morning’s drizzly and dreary start, it was nice to see the sun appear in the afternoon and brighten up things a bit. Even with the mix of clouds and sunshine today, conditions are nearly ideal for Labor Day festivities. In a town like ours that caters to those on vacation, we sometimes do not get the chance to partake in the holiday quite the same way as our visitors but hopefully folks are able to enjoy some time in the outdoors and/or with family and friends. Turning our sights ahead to the week, we add another day of school this week as we ramp up the start of the year. Something that was immediately noticed and felt by staff and students last week was the number of people in the building as compared to when we finished school in June. Our population at the end of the school year was about 550 and roughly 25 students were still in the virtual setting. As of Friday, we are officially hovering around 610 students although there is still some expected fluctuation that typically occurs at the start of every school year. As I shared with the staff Friday morning, I expect we will end up with just under 600 students but that is still 25 more than we were predicting. This underlies how fortunate we are to have the space provided by our still very new high school and how grateful we are to be here. -

Shapeshifting Citizenship in Germany: Expansion, Erosion and Extension Faist, Thomas

www.ssoar.info Shapeshifting Citizenship in Germany: Expansion, Erosion and Extension Faist, Thomas Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Arbeitspapier / working paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Faist, T. (2013). Shapeshifting Citizenship in Germany: Expansion, Erosion and Extension. (COMCAD Working Papers, 115). Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld, Fak. für Soziologie, Centre on Migration, Citizenship and Development (COMCAD). https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-51028-5 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

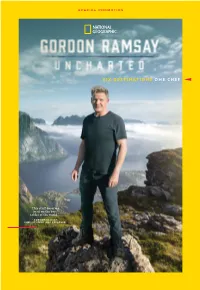

Gordon Ramsay Uncharted

SPECIAL PROMOTION SIX DESTINATIONS ONE CHEF “This stuff deserves to sit on the best tables of the world.” – GORDON RAMSAY; CHEF, STUDENT AND EXPLORER SPECIAL PROMOTION THIS MAGAZINE WAS PRODUCED BY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL IN PROMOTION OF THE SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: CONTENTS UNCHARTED PREMIERES SUNDAY JULY 21 10/9c FEATURE EMBARK EXPLORE WHERE IN 10THE WORLD is Gordon Ramsay cooking tonight? 18 UNCHARTED TRAVEL BITES We’ve collected travel stories and recipes LAOS inspired by Gordon’s (L to R) Yuta, Gordon culinary journey so that and Mr. Ten take you can embark on a spin on Mr. Ten’s your own. Bon appetit! souped-up ride. TRAVEL SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: ALASKA Discover 10 Secrets of UNCHARTED Glacial ice harvester Machu Picchu In his new series, Michelle Costello Gordon Ramsay mixes a Manhattan 10 Reasons to travels to six global with Gordon using ice Visit New Zealand destinations to learn they’ve just harvested from the locals. In from Tracy Arm Fjord 4THE PATH TO Go Inside the Labyrin- New Zealand, Peru, in Alaska. UNCHARTED thine Medina of Fez Morocco, Laos, Hawaii A rare look at Gordon and Alaska, he explores Ramsay as you’ve never Road Trip: Maui the culture, traditions seen him before. and cuisine the way See the Rich Spiritual and only he can — with PHOTOS LEFT TO RIGHT: ERNESTO BENAVIDES, Cultural Traditions of Laos some heart-pumping JON KROLL, MARK JOHNSON, adventure on the side. MARK EDWARD HARRIS Discover the DESIGN BY: Best of Anchorage MARY DUNNINGTON 2 GORDON RAMSAY: UNCHARTED SPECIAL PROMOTION 3 BY JILL K. -

Z-Nation - EP 2XX - FULL PINK (10/10/15) 2

EPISODE 200 "PEACE OF MURPHY" Written by REDACTED Directed by REDACTED PRODUCTION DRAFT 08/01/15 FULL BLUE 08/05/15 The Asylum Los Angeles 45315 FADE IN: 1 EXT. COUNTRY ROAD - DAY 1 We open on a desolate stretch of back-road. The mid-day sun beats down. There’s no noise. No crickets chirping. Like most places in this world: dead and way too quiet. A RUSTED BILLBOARD casts a shadow across the sweltering tarmac. A cartoon bear warning visitors that “ONLY YOU CAN PREVENT FOREST FIRES”. Behind the billboard, in the distance - AN ATOMIC FIRE RAVAGES THE LANDSCAPE. SLOW FOOTSTEPS break the silence. A WOUNDED-MAN drags himself down the road. Blackened and burned: The clothes are literally falling from his back. He’s sick and desperate - A victim of radiation poisoning. The Wounded-Man reaches the shadow of the billboard before stumbling - And collapsing to his knees. He looks towards the sky. Coughs. WOUNDED-MAN Please. Somebody... Anybody? ANGLE ON: A VEHICLE APPROACHING FROM THE DISTANCE The man smiles, his prayers have been answered. WOUNDED-MAN (CONT’D) Oh God, stop. Please stop. He climbs to his feet with what strength he can muster and frantically waves his arms around. The Truck continues its approach - It’s not slowing down. He realizes - and DASHES to the side - just as the vehicle speeds past. SCREECH! - The Truck comes to a complete stop just past the billboard. Brake-lights shine. The truck reverses back towards the bewildered man. The driver side window rolls down, revealing the mans savior - MURPHY sitting at the wheel with ROBERTA riding shotgun. -

Portrait of Rashid Johnson

Rosen, Miss. “View a Series of Portraits of Extraordinary Black Artists,” Dazed, June 6, 2017. “Portrait of Rashid Johnson and Sanford Biggers, The Ambassadors”, 2017 oil on canvas painting: 120 5/16 x 85 5/8 inches (305.6 x 217.5 cm) framed: 131 5/16 x 96 11/16 x 4 1/2 inches (333.5 x 245.6 x 11.4 cm)© Kehinde Wiley, courtesy Sean Kelly, New York The Trickster exists in different cultures around the globe: the wily shapeshifter with the power to transform the way we see the world. As an archetype, The Trickster can be found in any walk of life where people must operate according to more than one set of rules, moving seamlessly between the appearance of things and the underlying truth. Artists know this realm well for they are consigned to delve deep below the surface and manifest what they find. Yet their discoveries are not necessarily in line with the status quo; more often than not, they will upset polite society and upend respectability politics by speaking truth to power – quite literally. In the United States, African Americans know this well. Throughout the course of the nation’s history, they have been forced to deal with systemic oppression and abuse in a culture filled with double speak that began with the words “All men are created equal,” penned in the Declaration of Independence by Thomas Jefferson, a man who kept his own children as slaves until his death. Throughout his career, artist Kehinde Wiley has moved smoothly between spheres of influence, using the canon of Western art as a tool of subversion, celebration, and recognition for those who have long been excluded from the narrative. -

Overexpression of Glut4 Protein in Muscle Increases Basal and Insulin-Stimulated Whole Body Glucose Disposal in Conscious Mice

Overexpression of Glut4 protein in muscle increases basal and insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal in conscious mice. J M Ren, … , J M Amatruda, G I Shulman J Clin Invest. 1995;95(1):429-432. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI117673. Research Article The effect of increased Glut4 protein expression in muscle and fat on the whole body glucose metabolism has been evaluated by the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp technique in conscious mice. Fed and fasting plasma glucose concentrations were 172 +/- 7 and 78 +/- 7 mg/dl, respectively, in transgenic mice, and were significantly lower than that of nontransgenic littermates (208 +/- 5 mg/dl in fed; 102 +/- 5 mg/dl in fasting state). Plasma lactate concentrations were higher in transgenic mice, (6.5 +/- 0.7 mM in the fed and 5.8 +/- 1.0 mM in fasting state) compared with that of non- transgenic littermates (4.7 +/- 0.3 mM in the fed and 4.2 +/- 0.5 mM in fasting state). In the fed state, the rate of whole body glucose disposal was 70% higher in transgenic mice in the basal state, 81 and 54% higher during submaximal and maximal insulin stimulation. In the fasting state, insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal was also higher in the transgenic mice. Hepatic glucose production after an overnight fast was 24.8 +/- 0.7 mg/kg per min in transgenic mice, and 25.4 +/- 2.7 mg/kg per min in nontransgenic mice. Our data demonstrate that overexpression of Glut4 protein in muscle increases basal as well as insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal. -

Seec Form 30 Cover Page

SEEC FORM 30 Electronic Filing Itemized Campaign Finance Disclosure Statement CONNECTICUT STATE ELECTIONS ENFORCEMENT COMMISSION Revised February 2015 Do Not Mark in This Space For Official Use Only Page 1 of 51 COVER PAGE 1.NAME OF COMMITTEE 2. TYPE OF COMMITTEE x Candidate Committee EVA For Newtown _ Exploratory Committee 3. TREASURER NAME First MI Last Suffix Maureen Crick Owen 4. TREASURER ADDRESS Street Address City State Zip Code 16 Tamarack Rd Newtown CT 06470 5. ELECTION DATE 6. OFFICE SOUGHT ( Complete only if Candidate Committee) 7. DISTRICT NUMBER ( if applicable 11/08/2016 State Representative R106 8. CANDIDATE NAME (Complete only if Candidate or Exploratory Committee) First MI Last Suffix Eva Bermudez Zimmerman 9. TYPE OF REPORT Optional Itemized Statement for Pre-Grant Application Review (May) - Amendment 10. PERIOD COVERED Beginning Date Ending Date 04/01/2016 thru 04/30/2016 11. CERTIFICATION I hereby certify and state, under penalties of false statement, that all of the information set forth on this Itemized Campaign Finance Disclosure Statement for the period covered is true, accurate and complete. Electronic Filing Maureen Owen 03/14/2017 1:22:19PM SIGNATURE PRINT NAME OF THE SIGNER DATE CERTIFIED A Person who is found to have knowingly and willfully violated any provisions of the campaign finance statutes faces a civil penalty of up to $25,000, unless a fine of a larger amount is otherwise provided for as a maximum fine in the Connecticut General Statutes. Page 2 of 51 SEEC FORM 30 Itemized Campaign Finance Disclosure Statement CONNECTICUT STATE ELECTIONS ENFORCEMENT COMMISSION Revised February 2015 SUMMARY PAGE TOTALS NAME OF COMMITTEE (Provide Complete Name as Registered with Commission) TYPE OF REPORT EVA For Newtown Optional Itemized Statement for Pre-Grant Application Review (May) - Amendment COLUMN A COLUMN B This Period Aggregate 12. -

"Goodness Without Godness", with Professor Phil Zuckerman

4 The Secular Circular Newsletter of the Humanist Society of Santa Barbara www.SBHumanists.org FEBRUARY 2016 February Program: William Meller, M.D.: Medical Myths Medicine, like every other human endeavor, is rife with mythmaking. We seem to be prone to creating myths; stories about ourselves, our pasts and our world that attempt to explain how we got here and how we should behave. We hear them so often that we come to believe they are true. Sometimes they are helpful and enable us to act more like our heroes, but many times they are not. Often our myths directly contradict our immediate knowledge and experience. Yet we just as often take actions based on those myths despite all evidence to the contrary. Doctors are not only the creators of myths but also the unwitting believers in unchallenged myths that guide our everyday practice of medicine. In the past few years a movement called Evidence-Based Medicine has arisen to try to combat these myths or what is known as standard practice. But believe it or not, not all physicians believe that evidence is the best basis for medicine! This talk will address many of the most common myths in medical practice today. Beliefs regarding aging, diet, weight loss, exercise, disease prevention, healing, depression and other mental states, pregnancy and even the common cold will be examined as to their origin, why we hold onto them so closely, and what the evidence is that either supports or more commonly refutes them. Be prepared, be skeptical and be healthy! William Meller, M.D., is a practicing Internist in Santa Barbara. -

The Lantern, 2019-2020

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College The Lantern Literary Magazines Ursinusiana Collection Spring 2020 The Lantern, 2019-2020 Colleen Murphy Ursinus College Jeremy Moyer Ursinus College Adam Mlodzinski Ursinus College Samuel Ernst Ursinus College Lauren Toscano Ursinus College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/lantern See P nextart of page the forFiction additional Commons authors, Illustr ation Commons, Nonfiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Murphy, Colleen; Moyer, Jeremy; Mlodzinski, Adam; Ernst, Samuel; Toscano, Lauren; Tenaglia, Gabriel; Banks, Griffin; McColgan, Madison; Malones, Ria; Thornton, Rachel; DeMelfi, Gabby; Worcheck, Liam; Savage, Ryan; Worley, Vanessa; Schuh, Aviva; Bradigan, Emily; Addis, Kiley; Kushner, Shayna; Leon, Kevin; Armstrong, Tommy; Schmitz, Matthew; Drury, Millie; Lozzi, Jenna; Buck, Sarah; Ercole, Cyn; Mason, Morgan; Partee, Janice; Rodak, Madison; Walker, Daniel; Gagan, Jordan; Yanaga, Brooke; Foley, Kate I.; Li, Matthew; Brink, Zach; White, Jessica; Dziekan, Anastasia; Perez, Jadidsa; Abrahams, Ian; Reilly, Lindsey; Witkowska, Kalina; Cooney, Kristen; Paiano, Julia; Halko, Kylie; Eckenrod, Tiffini; and Gavin, Kelsey, "The Lantern, 2019-2020" (2020). The Lantern Literary Magazines. 186. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/lantern/186 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ursinusiana Collection at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been -

Amazon and IMDB Sued for Not Respecting Elders | Page 1

Amazon And IMDB Sued FOr Not Respecting Elders | Page 1 Amazon And IMDB Sued FOr Not Respecting Elders By: Jack Greiner on October 19, 2011 on graydon.law Well, sort of. An actress who identifies herself as Jane Doe has sued the Internet Movie Database Web site, and its parent company, Amazon, for revealing her actual age. I’m not making that up. Here’s the actual complaint, which was filed in a federal court in Seattle. In case you haven’t used it, IMDB is a Web site that has detailed information on any movie ever made. I personally love it. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve watched a movie on TV and wondered who the actor was in some small role, and where I’d seen him before. IMDB has all that information. But I digress. According to the complaint, Jane Doe is of Asian descent, and her given name is difficult for Americans to spell and pronounce. She has for that reason used a stage name throughout her career. She is also very careful not to provide personal information, including her true age. According to the complaint, “[i]n the entertainment industry, youth is king. If one is perceived to be “over-the-hill” i.e., approaching 40, it is nearly impossible for an up-and-coming actress, such as plaintiff, to get work.” IMDB also offers a service called IMDbPro, which offers “industry insider” information to paying customers. Ms. Doe signed up for the service and in so doing, provided her name, birth date and other personal information. -

KSD Middle School Athletic Handbook

MIDDLE SCHOOL 2019 – 2020 ATHLETIC HANDBOOK CEDAR HEIGHTS MERIDIAN KENT MILL CREEK MATTSON NORTHWOOD MEEKER SUMMIT TRAIL TAHOMA MAPLE VIEW TABLE OF CONTENTS KENT-TAHOMA LEAGUE SPORT CHAIRPERSONS .............................................................................. i ACTIVITIES, POLICIES, & PRACTICES I. Introductory Statement...........................................................................................................................1 II. Eligibility ...............................................................................................................................................1 III. League Sports.........................................................................................................................................2 IV. Playing Regulations ...............................................................................................................................2 V. Scheduling..............................................................................................................................................2 VI. Trophies and Awards .............................................................................................................................3 VII. School Visitation ....................................................................................................................................3 VIII. Scouting .................................................................................................................................................3 IX. -

LEHIGH NCAA TOURNAMENT QUALIFIERS 2021 Career Career Bonus EIWA SOCIAL MEDIA 125 #14 Jaret Lane (Jr., Catawissa, Pa.) 8-0 33-13 21 1St

WRESTLING MATCH NOTES 2020-21 SCHEDULE LEHIGH MOUNTAIN HAWKS (3-4, 3-1 EIWA)) JJanuaryanuary THE 90TH NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS 2 HHOFSTRA*OFSTRA* CCanceledanceled 9 aatt NNo.o. 1133 PPittsburghittsburgh LL,, 224-94-9 Mar. 18-20, 2021 1166 aatt NNavy*avy* LL,, 221-91-9 Enterprise Center - St. Louis, Mo. Video: ESPN Family of Networks, 2244 DDREXEL*REXEL* CCanceledanceled ESPN3/ESPN App 3300 NNo.o. 2255 BBINGHAMTON*INGHAMTON* WW,, 119-169-16 3311 LLIU*IU* WW,, 446-06-0 FFebruaryebruary 6 AARMYRMY WWESTEST PPOINT*OINT* WW,, 118-168-16 6 NNo.o. 1144 NNORTHORTH CCAROLINAAROLINA LL,, 226-66-6 7 RRIDERIDER LL,, 117-157-15 1133 AAMERICAN*MERICAN* CCanceledanceled 1144 BBUCKNELL*UCKNELL* CCanceledanceled 2266 aatt EEIWAIWA CChampionshipshampionships ((Manheim,Manheim, PPa.)a.) 11st,st, 1158.558.5 ppts.ts. MMarcharch 118-208-20 aatt NNCAACAA CChampionshipshampionships ((St.St. LLouis)ouis) HHomeome ddualsuals iinn BBOLDOLD CCAPSAPS **EIWAEIWA OOpponentpponent AAllll hhomeome ddualsuals fforor 22020-21020-21 sseasoneason wwillill bbee hheldeld iinn LLeeman-Turnereeman-Turner AArenarena aatt GGracerace HHallall TEN LEHIGH WRESTLERS SET FOR NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS After winning its fourth straight EIWA championship on Feb. 26, Lehigh qualified a full squad of 10 wres- tlers for the 90th NCAA Championships at Enterprise Center in St. Louis. Lehigh crowned four individual SPORTS COMMUNICATIONS champions and placed all 10 EIWA entrants in the top five of their respective weight classes. Leading the way for the Lehigh contingent is senior Jordan Wood, the No. 8 seed at 285, who recently won his fourth Director, Communications (Wrestling SID) . Steve Lomangino individual EIWA title. All four individual EIWA champions earned seeds in the top 17.