Arxiv:1807.10227V2 [Quant-Ph] 8 Nov 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avoided Crossings in Photochemistry

AVOIDED CROSSINGS IN PHOTOCHEMISTRY ALAIN DEVAQUET Laboratoire de Chimie Theorique, Centre Scientflque d'Orsay, Université de Paris-Sud, 91405 ORSA Y, France ABSTRACT Two families of avoided crossings exist: (a) geometry-dependent, and (b) model-dependent. They are consequences of one of three possible molecular orbital patterns (allowed crossing, weakly avoided crossing and near-touching situations). All these cases are illustrated here and their mechanistic implications investigated both in terms of static potential energy surfaces and of dynamic Landau—Zener transition probabilities. The non-crossing rule for potential energy curves of diatomic molecules was demonstrated fifty years ago"2. Its extension to the general case of the potential energy surfaces of polyatomic molecules was only published very recently3'4. This long period of time might indicate that this fundamental rule, though invoked very frequently, has not yet received the full attention it deserves. Indeed, in organic photochemistry, its mechanistic implications have only been recognized during the past ten years. This was mainly due to the Woodward and Hoffmann pioneering study of forbidden thermal and allowed photochemical reactions5. On the other hand Van der Lugt and Oosterhoff were the first to emphasize the importance of avoided crossing regions as likely leakage channels from an excited state toward the ground state of reacting systems. Their calculations of the potential energy surfaces for the photochemically allowed closure of butadiene to cyclobutene beauti- fully illustrate this fact6. Our goal in this paper is to review the various aspects of the avoided crossing problem. After a brief outline of its theoretical treatment we shall discuss this phenomenon in terms of electronic states and then, more precisely, at the molecular orbital level. -

Molecular Dynamics Beyond the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Mixed Quantum–Classical Approaches

John von Neumann Institute for Computing Molecular Dynamics Beyond the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Mixed Quantum–Classical Approaches Nikos L. Doltsinis published in Computational Nanoscience: Do It Yourself!, J. Grotendorst, S. Bl¨ugel, D. Marx (Eds.), John von Neumann Institute for Computing, J¨ulich, NIC Series, Vol. 31, ISBN 3-00-017350-1, pp. 389-409, 2006. c 2006 by John von Neumann Institute for Computing Permission to make digital or hard copies of portions of this work for personal or classroom use is granted provided that the copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise requires prior specific permission by the publisher mentioned above. http://www.fz-juelich.de/nic-series/volume31 Molecular Dynamics Beyond the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Mixed Quantum–Classical Approaches Nikos L. Doltsinis Chair of Theoretical Chemistry Ruhr-Universit¨at Bochum 44780 Bochum, Germany E-mail: [email protected] This contribution takes a closer look at the foundations of conventional molecular dynamics simulations such as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation and the treatment of atomic nuclei according to the laws of classical mechanics. Regimes of validity of the adiabatic approximation are defined and models that take into account nonadiabatic effects in situations where the Born- Oppenheimer approximation breaks down are introduced. We focus on two mixed quantum- classical methods that differ only in the way the forces on the — classical — atomic nuclei are determined from the solutions to the time-independent electronic Schr¨odinger equation. In the Ehrenfest approach, the system moves on a single potential energy surface obtained by weighted averaging over all adiabatic states, whereas the ’surface hopping’ method allows transitions between pure adiabatic potential energy surfaces according to their weights. -

Semiclassical Computational Methods for Quantum Dynamics with Band

Semiclassical computational methods for non-adiabatic quantum dynamics with uncertainty Shi Jin University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA collaborators • Nicolas Crouseilles, Rennes • Mohammed Lemou, Rennes • Liu Liu, Austin (UQ part) The prototype PDEs to be solved • Systems of linear transport equations with oscillatory forces or initial data • The system is coupled through the force • Part of the force simulates the (non-adiabatic) phase information; • The interaction term resembles the Berry connection in quantum dynamics • Random uncertainty in band-gap, or initial data • Solutions highly oscillatory in space, time and uncertainty variables Computational difficulty • Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem: need a few grid points per wave length • This is a daunting talk for most high frequency waves, including quantum dynamics, compuations in high dimensions Goal develop schemes that can get the correct (pointwise) solutions without resolving the oscillations and the numerical schemes converge uniformly in \epsilon -- defies the Nyquist-Shannon sampling restriction in certain degree Motivation: Band crossings: non-adiabatic qunatum phenomena Inter-band transition is a general quantum mechanical Phenomenon; it causes difficulties in semi-classical approximations • Born-Oppenheimer approximation: non-adiabatic surface hopping • Bloch decomposition in quantum dynamic with periodic potentials: crossing of Bloch bands or influence of external potentials • elastic and electromagnetic waves with polarization effect • Graphene: coupling of different -

Exact Solution of Multi State Problems in Quantum and Statistical Mechanics

Exact solution of Multi state problems in Quantum and Statistical Mechanics A THESIS submitted by DIWAKER for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF BASIC SCIENCES INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MANDI. MANDI-175005 (H. P.) INDIA AUGUST, 2015 c 2015 - Diwaker All rights reserved. I dedicate this thesis to my parents, my brothers, my sisters and to my teachers. Indian Institute of Technology BArtFy þODOEgkF s\-TAn Mandi, Mandi (H. P.)-175005, m\ÚF, m\ÚF,(Eh. þ.)-175005, India, Govt. of India BArt, BArt srkAr THESIS CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis titled Exact Solution of Curve Crossing Problems in Quantum Mechanics, submitted by Diwaker, to the Indian Institute of Technology, Mandi, for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, is a bonafide record of the research work done by him under my supervision. The contents of this thesis, in full or in parts, have not been submitted to any other Institute or University for the award of any degree or diploma. Dr. Aniruddha Chakraborty Research Guide Associate Professor School of Basic Sciences IIT-Mandi, 175005 Phone-01905-237930 Email-achakraborty @iitmandi.ac.in http://www.aniruddhachakraborty.org/ Place: Mandi (H. P.) Date: 1st august 2015 Phone: 01905-237949/237944/267001, Fax: 01905-267009, www.iitmandi.ac.in Indian Institute of Technology BArtFy þODOEgkF s\-TAn Mandi, Mandi (H. P.)-175005, m\ÚF, m\ÚF,(Eh. þ.)-175005, India, Govt. of India BArt, BArt srkAr DECLARATION BY RESEARCH SCHOLAR I hereby declare that the entire work assimilated in this thesis entitled Exact Solution of Curve Crossing Problems in Quantum Mechanics is the result of investigations carried out by me in the School of Basic Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, under the supervision of Dr. -

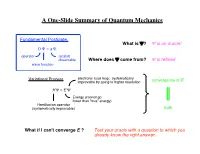

A One-Slide Summary of Quantum Mechanics

A One-Slide Summary of Quantum Mechanics Fundamental Postulate: What is !? ! is an oracle! O ! = a ! operator (scalar) observable Where does ! come from? ! is refined wave function Variational Process electronic road map: systematically improvable by going to higher resolution convergence of E H ! = E ! Energy (cannot go lower than "true" energy) Hamiltonian operator (systematically improvable) truth What if I can't converge E ? Test your oracle with a question to which you already know the right answer... Photoaffinity Labeling 1 N3 h! NH binder binder –N2 singlet nitrene covalently ligand with attached modifies enzyme — active photoaffinity label in site can be identified by enzyme active site sequencing of protein Photoaffinity Labeling 2 Attractive features of aromatic nitrenes as photoaffinity labels: 1) Generated with light outside of protein absorption bands 2) Highly reactive singlets 3) N2 is an innocuous byproduct of activation But: bond insertion k1 N3 N h! kISC ISC to triplet state (H-atom abstraction) –N2 k3 N singlet Practical concern—must minimize didehydroazepine Photoaffinity Labeling 3 bond insertion k1 N3 N h ! kISC ISC to triplet state (H-atom abstraction) –N2 k3 N singlet didehydroazepine N N N F F F F k3 > k1 k1 > k3 k3 > k1 Platz et al. Configuration Cartoons N N 3 1 A2 (T0) A2 (S1) N N 1 1 1 A1 (S2) 2 A1 (S3) Relative E (kcal/mol) for PhN ! . N : . 3 1 1 1 " A2 A2 1 A1 2 A1 MRCISD/DZP 0.0 21.0 39.8 (52) CASPT2N(8,8)/TZP 0.0 19.3 34.8 54.5 CCSD(T)/DZP 0.0 — 35.2 (47.2) BLYP/TZP 0.0 (14.3) 29.5 (41.0) Expt. -

How to Detect Level Crossings Without Looking at the Spectrum

How to detect level crossings without looking at the spectrum M. Bhattacharya Department of Physics, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 (Dated: October 22, 2018) We remind the reader that it is possible to tell if two or more eigenvalues of a matrix are equal, without calculating the eigenvalues. We then use this property to detect (avoided) crossings in the spectra of quantum Hamiltonians representable by matrices. This approach provides a pedagogical introduction to (avoided) crossings, is capable of handling realistic Hamiltonians analytically, and offers a way to visualize crossings which is sometimes superior to that provided by the spectrum. We illustrate the method using the Breit-Rabi Hamiltonian to describe the hyperfine-Zeeman structure of the ground state hydrogen atom in a uniform magnetic field. PACS numbers: 03.75.Be, 03.75.Lm, 84.40.Az, 73.21.Cd I. INTRODUCTION In this article we employ an algebraic method that ad- dresses these basic questions as well as some others. It Crossings and avoided crossings occur in the spectra allows for a simple but systematic approach to (avoided) of many physical systems such as atoms,1 molecules,2 crossings. In describing this approach we reintroduce to semiconductors3 and microwave cavities.4 They can oc- the study of (avoided) crossings a very useful but perhaps 10,11,12,13 cur as a result of tuning an external (e.g. electric) field5 neglected mathematical tool, the discriminant. 14,15,16 or as the consequence of varying an internal (e.g. in- In a series of articles, we have demonstrated in de- ternuclear) coordinate,6 for instance. -

Research 1..5

Letter pubs.acs.org/JPCL Cavity Femtochemistry: Manipulating Nonadiabatic Dynamics at Avoided Crossings Markus Kowalewski,* Kochise Bennett, and Shaul Mukamel* Chemistry Department, University of California, Irvine, California 92697-2025, United States ABSTRACT: Molecular potential energy surfaces can be actively manipulated by light. This is usually done by strong classical laser light but was recently demonstrated for the quantum field in an optical cavity. The photonic vacuum state of a localized cavity mode can be strongly mixed with the molecular degrees of freedom to create hybrid field-matter states known as polaritons. We simulate the avoided crossing of sodium iodide in a cavity by incorporating the quantized cavity field into the nuclear wave packet dynamics calculation. The quantized field is represented on a numerical grid in quadrature space, thus avoiding the limitations set by the rotating wave approximation (RWA) when the field is expanded in Fock space. This approach allows the investigation of cavity couplings in the vicinity of naturally occurring avoided crossings and conical intersections, which is too expensive in the fock space expansion when the RWA does not apply. Numerical results show how the branching ratio between the covalent and ionic dissociation channels can be strongly manipulated by the optical cavity. he photochemistry of molecules can be significantly level system linearly coupled to a quantized radiation field is − T influenced by specially tailored electromagnetic fields.1 7 given by the quantum Rabi model27 While control is usually achieved with classical laser fields, a ̂ strong coupling with the vacuum state of a cavity utilizes the Hec=++HHH e c I quantum nature of the electromagnetic mode. -

Avoided Level Crossings in Open Quantum Systems

Avoided level crossings in open quantum systems Hichem Eleuch and Ingrid Rotter∗ Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems, D-01187 Dresden, Germany (Dated: June 12, 2012) Abstract At high level density, two states avoid usually crossing at the critical value acr of the parameter a by which the system is controlled. The wavefunctions of the two states are mixed in a finite parameter range around acr. This holds true for discrete states as well as for narrow resonance states which are coupled via the environment of scattering wavefunctions. We study the influence of avoided level crossings onto four overlapping complex eigenvalues of a symmetric non-Hermitian operator. The mixing of the two wavefunctions around acr is simulated, in each case, by assuming a Gaussian distribution around acr. At high level density, the Gaussian distributions related to avoided crossings of different levels may overlap. Here, new effects arise, especially from the imaginary part of the coupling term via the environment. The results show, moreover, the influence of symmetries onto the multi-level avoided crossing phenomenon. arXiv:1206.2162v1 [quant-ph] 11 Jun 2012 ∗ [email protected] 1 I. INTRODUCTION Avoided level crossings play an important role in quantum mechanics. They are known for about 80 years [1]. In the case that the Hamilton operator of the system is Hermitian and the real eigenvalues Ei provide the energies of the discrete states of the system, two of its states never will cross. Instead they avoid crossing when controlled by a parameter. This phenomenon is an observable effect: it consists in an exchange of the two states, including their populations, in a many-particle system. -

Molecular Dynamics with Quantum Transitions (MDQT): a Match Made in Phase Space

Molecular Dynamics with Quantum Transitions (MDQT): A Match Made in Phase Space Kristin Benke & Morgan Hammer December 4, 2014 1 Introduction Molecular dynamics (MD) is a field of study in computational chemistry concerned with describing and simulating the motion of atoms and molecules in time. Such simulations give information about time-dependent physical and chemical processes as well as provide statistical information such as diffusion coefficients, heat capacities, or time-correlation functions for a chemical system of interest. To ease computational cost, most of these MD simulations are conducted treating the system classically. However, in systems where quantum effects such as tunneling, quantum interference, zero point energy are significant such as for low temperature systems or systems involving hydrogen atoms, using fully classical MD can give inaccurate results. Molecular dynamics methods can be modified to describe select quantum effects. The methods described by Tully provide a modified molecular dynamics method to incorporate electronic transitions. In quantum mechanics, all the information about nuclei and electrons is contained within a wave function obtained by solution of the Schrodinger¨ equation. Manipulation of such a wave function requires treatment of a number of degrees of freedom that is not reasonably tractable with the computational power currently available for all but the smallest of systems. The nuclear-electronic wave function requires digestion before it can be fed into any algorithm to extract interesting information. First, the nuclear and electronic degrees of freedom can be decoupled in accordance with the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. Because the nuclei move on such a slower time-scale than the electrons and if a molecule remains on only its electronic ground state, the nuclei can be treated as classical particles moving through an effective potential of their electron clouds. -

1 Adiabatic and Diabatic Representations

Advanced kinetics Solution 6 April 8, 2016 1 Adiabatic and diabatic representations 1.1 Born-Oppenheimer approximation The time-independent Schr¨odingerequation for both electronic and nuclear degrees of freedom is H^ Ψ(r; R) = E Ψ(r; R); (1) where the full molecular Hamiltonian reads (in atomic units, whereh ¯ = e = me = 1=(4π0) = 1) H^ = T^e + V^e + T^N + V^N + V^eN (2) X 1 X 1 X 1 X Zi Zj X Zj = − r2 + − r2 + − : (3) 2 e;i jr − r j 2 M N;i jR − R j jr − R j i j>i i j i i j>i i j ij i j We use fr; reg to refer to electron coordinates and momenta and fR; rNg for nuclear co- ordinates and momenta. Zi are the nuclear charges and Mi are the masses of the nuclei i. (both being expressed as multiples of the electron charge and electron mass, respectively). Equation (2) provides a shorthand notation for the five terms in Eq. (3), namely electron ki- netic energy, electron-electron repulsion, nuclear kinetic energy, nuclear-nuclear repulsion and electron-nuclear attraction. By defining the electronic Hamiltonian H^e = T^e + V^e + V^eN; (4) we get the eigen-energies Eel(R) from the electronic Schr¨odingerequation: el H^e Ψ(r; R) = E (R) Ψ(r; R): (5) We now insert the wavefunction described below Ψ(r; R) = (r; R) χ(R); (6) into Eq. (1), we get el H^ (r; R) (r; R) χ(R) = (T^N + E (R) + V^N) (r; R) χ(R) (7) = E (r; R)χ(R): (8) The Laplacian in the nuclear kinetic energy operator of the full wavefunction can be rewritten as: 2 rN;iΨ(r; R) = rN;i [rN;i (r; R) χ(R)] = rN;i [χ(R) rN;i (r; R) + (r; R) rN;i χ(R)] 2 = rN;i χ(R) · rN;i (r; R) + χ(R) rN;i (r; R) 2 +rN;i (r; R) · rN;i χ(R) + (r; R) rN;i χ(R) 2 = (r; R) rN;i χ(R) + 2 rN;i (r; R) · rN;i χ(R) 2 +χ(R) rN;i (r; R): (9) 1 Advanced kinetics Solution 6 April 8, 2016 As a result, Eq. -

Introduction to Quantum & Computational Chemistry For

Introduction to Quantum & Computational Chemistry for Electronically Excited States Lecture 4 Target: Computer simulations are employed to study the structure and reactivity of single molecules and molecular systems (molecule in solution on in a macromolecular cavity). Tools: We need a series of software technologies to describe the electronic and geometrical structure of molecules and their time evolution. (visit http://www.lcpp.bgsu.edu) The (3N-6 Dimensional) Potential Energy Surface of a Chemical Reaction [T (R) + Vnn(R) + Eel(R)] Photochemical Reaction Path Excited State Conical Intersection (CI) or A* “Photochemical Funnel” 1966 Zimmerman, 1972 Michl B hν A* Ground State CI hν B Energy A A Excited State Ground State Minimum Energy Paths Reaction Coordinate Photochemical Reaction Path Stationary Point Singularity Transition Vector (X 1) Branching (or g-h) plane (X1, X2) TS CI A* A X X1 2 X1 B B A One Product One or More Product Benzene Photochemistry (excited state) (primary) (secondary) h ν 254 nm liquid state prefulvene benzvalene under N2 (q.y. 0.02) (e.g. Turro 1986) N of photoproduct molecules N of absorbed photons Ground state diradical intermediate Benzene Conical Intersection: Structure unpaired electrons ground state 1.4 Å allyl radical 2.0 Å half-broken bond 1.4 Å This conical intersection defines the "prefulvene" path Benzene Conical Intersection:Branching Space ΨB ΨA diradical CI Energy Kekule Excited State Ground State Reaction Coordinate The wavefunction (electronic structure) does not change when passing through the -

A Kekulé-Crossing Model for the “Anomalous” Behavior of the B2u

VOLUME 29 NUMBER 5 ® MAY 1996 Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office; Copyright 1996 by the American Chemical Society A Kekule´-Crossing Model for the “Anomalous” Behavior of the b2u Modes of Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Lowest 1 Excited B2u State SASON SHAIK,*,1a SHMUEL ZILBERG,1b AND YEHUDA HAAS*,1b Institute of Chemistry, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91904, Israel Received October 13, 1995 I. Introduction As shall be shown the model is general enough and can form a basis for thinking about delocalized ground This Account presents a model that provides a lucid states and their twin excited states made of the out- physical basis for the apparently unusual behavior of of-phase combination of the same set of Kekule´ 1 Kekule´-type vibrational modes in the 1 B2u excited structures. state of benzene and other aromatic hydrocarbons. The The frequency up-shift of the Kekule´-type b2u modes 1 model, called the Kekule´-crossing model, is based on in the 1 B2u electronically excited state of several 1 the idea that the electronic ground state (1 A1g) and aromatic hydrocarbons (benzene, naphthalene, an- 1 the first B2u excited state may be considered to a thracene, and some of their derivatives2-4) is well reasonable approximation as twin states, arising from documented and appears to be a general phenomenon. in- and out-of-phase combinations of the same Kekule´ For instance, the frequency of the skeletal mode 1 in 1 -1 Publication Date (Web): May 14, 1996 | doi: 10.1021/ar950206i structures. The Kekule´-crossing model is used to the 1 B2u state of benzene (the ν14 mode, 1570 cm ) account for other properties of these systems, and the is 261 cm-1 higher than that of the same mode in the 1 2 observed spectroscopic “anomaly” in fact provides the ground 1 A1g state.