Ecclesiology Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxfordshire Community Transport Directory 2020/21

Oxfordshire Community Transport Directory 2020/21 This directory brings together information about community transport groups and services in Oxfordshire. More about community transport Community transport is run by the community for the community, meeting needs that are not met in other ways. Some groups offer services just for their members, others are open to the public. Help and advice If you find that your area is not covered, you may wish to consider setting up a group to meet that need. If you are interested in finding out more please contact the Community Transport Team, Oxfordshire County Council at [email protected]. In addition, Community First Oxfordshire offers support and advice for existing and new community transport services and can be contacted by email [email protected] or call 01865 883488. Ability CIC District: Cherwell Area Covered: Banbury (surrounding villages) How to book: 01327 604123 Description: Timetabled routes through to Banbury Website: www.abilitycic.org.uk Abingdon & District Volunteer Centre Car Scheme District: Vale Area Covered: Abingdon How to book: 01235 522428 (10am-12:30pm only) Description: Taking people to health-related appointments. Whoever needs us due to challenged mobility. All Together In Charlbury District: West Area Covered: Charlbury How to book: 01993 776277 Description: All Together In Charlbury (ATIC) aims to provide informal help and support to people in the community who need it by linking them up with a Charlbury resident who has offered some of their time to meet requests. ATIC is here to help Charlbury residents of all ages and circumstances who, for whatever reason, are unable to carry out a task or trip themselves and who have no family or friends available to help. -

Elsfield Village Plan Report

Contents Foreword................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 2 2. Location and population.................................................................................................. 3 3. Social make-up of the village .......................................................................................... 3 4. The Process – how we set about working on the Parish Plan ........................................ 5 4.1 The ORCC briefing meeting and consultation exercise .......................................... 5 4.2 Initial consultation exercise ..................................................................................... 7 4.3 Establishing a formal Steering Group...................................................................... 7 4.4 The work of the steering group................................................................................ 7 5. Understanding current day Elsfield ................................................................................. 7 5.1 A picture of Elsfield residents in 2007 ..................................................................... 8 5.2 Existing committees ................................................................................................ 8 5.2.1 The Parish Meeting ........................................................................................ -

Beckley & Area Community Benefit Society Ltd Chairman's Report To

Beckley & Area Community Benefit Society Ltd Chairman’s Report to the Annual Members Meeting, 28 November 2018 Introduction: The introduction to my first Beckley & Area Community Benefit Society (BACBS) annual report, in November 2017, bears repetition with only minor editing: ‘BACBS was established in September 2016 in order to purchase The Abingdon Arms for the benefit of the community, and to secure its future as a thriving community-owned pub. It is now a welcoming free house which serves a range of local beers, good quality wine and soft drinks, and excellent freshly-cooked food prepared using locally sourced ingredients when possible. Our vision was, and is, for The Abingdon Arms to be at the heart of our community, accessible to all, a place to meet people, exchange ideas, and come together for recreational and cultural activities. In this way, BACBS aims to support a friendly, welcoming and cohesive community’. The Society’s second year of operation has seen both consolidation and exciting progress. BACBS is in good health, as will be evident from the Treasurer’s and Secretary’s reports. Highlights of the year include: The Abingdon Arms – Aimee Bronock, Joe Walton and their excellent front of house and kitchen teams have consolidated, then extended on the promise with which they commenced their tenancy of The Abingdon Arms in June 2017. It is once again a welcoming and vibrant country pub, serving both the local community and increasing numbers of visitors from further afield. The food, drinks and warm welcome they offer are greatly appreciated! In astonishingly short order, our tenants have achieved prestigious awards which affirm the quality of their stewardship of our community pub. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Public Transport in Oxford

to Woodstock to Kidlington, Bicester Nok e A y B C a and Wa ter Eaton P&R Wood W ze Frie 2.2A.2 B.2 C.2 D Public Transpor t in Oxford Pear Tr ee 2.2A.2 B.2 C.2 D S3 Park & Ride O A x 25.25 Ri f v o A er r 59.59 .94 C 300 d D L h e e i KEY n r d R 500.700 w i k e s o s ll e a 18 i d k S5.X88 853 W d e S2 a o L No o A v 4 to Witney rthe d rn s e Oxford Bus Company B t n Cutteslo we y- o Pa u ss c 218 R e . (including Brookes Bus) oad k Dr Templar Rd. 108 ile R M 10 o e 118 1 a Fiv 17 Stagecoach 1 d 108 700 Harefields Park & Ride St ow W ood Sunderland R Avenue Wo lv er cot e o Other operators (including Arriva, s n n Rd Elsfield X39 a r Carlto . H u m Heyfordian, Thames Tr avel & RH Tr ansport) R T o o u m a n t 17 N d s e d r o W 6 i orth Rd. r C F w t ent he y l W . r th n 108 a ad Sunn ymead B m Ro y 11 8 Godstow W -P S o A B C D as t o 2.2 .2 .2 .2 s r Upper e d R a s A B C D o Railway line and statio n t 2.2 .2 .2 .2 a m Lo we r Wo lv er cot e o d 108 c B A to Stanton k a 17.25.25 Wo lv er cot e n Oxford Green Belt Wa y R b A St. -

A Transport Service for Disabled and Mobility- Impaired People

Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride 0845 310 11 11 A transport service for disabled and mobility- impaired people operated by With financial support from What is Dial-a-Ride? Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride is a door-to-door transport service for those who are unable to use or who find it difficult to use conventional public transport, such as elderly or disabled people. The drivers of the vehicles are specially trained in the assistance of wheelchair users and those with mobility problems. Where can I go? Whatever your journey purpose*, Dial-a-Ride is available to take you! *The only exception is for journeys to hospitals for appointments. Please speak to your doctor about travel schemes to enable you to make your appointment . How do I qualify to use Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride? • You must be resident in Oxfordshire. • You can use Dial-a-Ride if you have a mobility or other condition which means that you cannot use, or find it difficult to use, conventional public transport. You don’t have to be registered disabled or be a wheelchair-user. For example, you might be unable to walk to the bus stop. • Age and nature of disability are irrelevant. Advantages of using Oxfordshire Dial-a-Ride When and where can I travel? The service is available between 9:00am and 5:00pm as follows: We want to make sure that the Dial-a-Ride service is available to as many members as possible, as fairly as possible, every day it operates. However, due to high demand, and to make best use of the buses, we serve certain areas on set days, allocating places to customers to travel on the day when the bus is in their area. -

Started to Break Up. Among the Females, the Single High

EVOLUTIONARY STUDIES ON MANIOLA JURTINA: THE ENGLISH MAINLAND, 1958-60 E. R. CREED Genetics Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Oxford W. H. DOWDESWELL Biology Department, Winchester College E. B. FORD and K. G. McWHIRTER Genetics Laboratory, Department of Zoology, Oxford Received5.X.6t 1.INTRODUCTION WEhave already demonstrateddemonstrated thatthat thethe A'IaniolaManiola jurtina populations in Southern England, from West Devon to the North Sea, are char- acterised by relatively low average spot-numbers, having a female frequency-distribution unimodal at o spots. Also that in East Cornwall thethe spottingspotting hashas aa higherhigher averageaverage valuevalue inin bothboth sexessexes andand isis bimodal,bimodal, at o and 2 spots, in the females (Creed et al., 1959). In 1956 we studied the transition between thethe twotwo typestypes inin aa transecttransect runningrunning twotwo milesmiles south of Launceston, approximately midway between the north and south Coastscoasts ofof thethe Devon-CornwallDevon-Cornwall peninsula.peninsula. We found that the one form of spotting changed abruptly to the other in a few yards without any barrier between them and that the distinction between the two increased as they approached each other (the "reversedine " effect). TheseThese features features persistedpersisted thethe followingfollowing year, yet the point of transition had shifted; for the East Cornish type had advanced three miles eastwards, indicating that the two spot-distributions represent alternative types of stabilisation. This situation is so exceptional that it seemed essential to test whether or not it is widespread along the interface between the Southern English and East Cornish forms and if it were maintained in subsequent years. The results of that investigation are described in this article. -

'Income Tax Parish'. Below Is a List of Oxfordshire Income Tax Parishes and the Civil Parishes Or Places They Covered

The basic unit of administration for the DV survey was the 'Income tax parish'. Below is a list of Oxfordshire income tax parishes and the civil parishes or places they covered. ITP name used by The National Archives Income Tax Parish Civil parishes and places (where different) Adderbury Adderbury, Milton Adwell Adwell, Lewknor [including South Weston], Stoke Talmage, Wheatfield Adwell and Lewknor Albury Albury, Attington, Tetsworth, Thame, Tiddington Albury (Thame) Alkerton Alkerton, Shenington Alvescot Alvescot, Broadwell, Broughton Poggs, Filkins, Kencot Ambrosden Ambrosden, Blackthorn Ambrosden and Blackthorn Ardley Ardley, Bucknell, Caversfield, Fritwell, Stoke Lyne, Souldern Arncott Arncott, Piddington Ascott Ascott, Stadhampton Ascott-under-Wychwood Ascott-under-Wychwood Ascot-under-Wychwood Asthall Asthall, Asthall Leigh, Burford, Upton, Signett Aston and Cote Aston and Cote, Bampton, Brize Norton, Chimney, Lew, Shifford, Yelford Aston Rowant Aston Rowant Banbury Banbury Borough Barford St John Barford St John, Bloxham, Milcombe, Wiggington Beckley Beckley, Horton-cum-Studley Begbroke Begbroke, Cutteslowe, Wolvercote, Yarnton Benson Benson Berrick Salome Berrick Salome Bicester Bicester, Goddington, Stratton Audley Ricester Binsey Oxford Binsey, Oxford St Thomas Bix Bix Black Bourton Black Bourton, Clanfield, Grafton, Kelmscott, Radcot Bladon Bladon, Hensington Blenheim Blenheim, Woodstock Bletchingdon Bletchingdon, Kirtlington Bletchington The basic unit of administration for the DV survey was the 'Income tax parish'. Below is -

SODC LP2033 2ND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT FINAL.Indd

South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT Appendix 5 Safeguarding Maps 209 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 210 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 211 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 212 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 213 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 214 216 Local Plan2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONSDOCUMENT South Oxfordshire DistrictCouncil South Oxfordshire South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 216 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 217 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 218 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 219 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 220 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS -

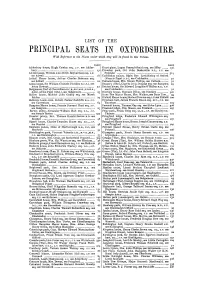

LIST of the Bicester ...••.. I ... I ...I ...I ...I...48

LIST OF THE With Reference to the Places under which they will be found in this Volume. PAGE PAGE Adderbury house, Hugh Cawley esq. J.P. see Adder- Court place, Logan Pearsall-Smith esq. see Iffiey ...... ; 136 bury .....•..........................•...............•.............. 17 Crowsley park, Col. John Baskerville D.L., J.P. see Adwell house, William John Birch Reynardson esq. J.P. Shiplake ···········~···········~································· 31'l see Adwell •..............•..............•...........•............ 18 Cuddesdon palace, Right Rev. Lord Bishop of Oxford Asthall Manor house, Arthur Charles Bateman esq. (Francis Paget D. D. ) , see Cuddesdon . .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 1 see Astball ..................................................... 21 Culham house, Mrs. Shawe Phillips, see Culham......... 91 Aston house, Sir William Chichele Plowden K.c.s.I. see Deanery (The), Charles Irvin Douglas esq. see Bampton 25 As ton Rowant .............••.••..•.......................•.••... 22 Denton house, Sir Edward Loughlin O'Malley M.-'.., J.P. Badgemore, Earl of Clanwilliam G.c. B. ,K.C.M.G. ,F.R.G.s., see Cuddesdon ······································~·········~· 91 Adml. of the Fleet (retd.), see Badgemore ............. .. 23 Ditchley house, Viscount Dill on, see Ditchley ............. 320 Baldon house, Michael John Godby esq. see Marsh Duns Tew Manor House, Mrs. Walker, see Duns Tew... 99 Baldon ..................................... ····~· ...........•...... 24 Elsfield Manor house,HerbertParsons esq.J.P.see Elsfield 100 Balmore, -

Original Proforma with Electorate Projections

South Oxfordshire District - North Didcot Check your data 2011 2018 Number of councillors: 36 36 Overall electorate: 103,017 108,515 Average electorate per cllr: 2,862 3,014 What is the What is the Is there any other description you use current predicted for this area? electorate? electorate? Electorate Electorate Description of area 2012 2018 Example 1 480 502 Example 2 67 68 Example 3 893 897 Example 4 759 780 Example 5 803 824 Didcot All Saints ward 4247 6643 Didcot Ladygrove ward 5843 7599 Didcot Northbourne ward 4105 4009 Didcot Park ward 4435 4675 Henley North ward 4471 4534 Henley South ward 4711 4754 Thame North ward 4449 4355 Thame South ward 4598 4869 Wallingford North ward 4640 4561 Cholsey and Wallingford South 4126 5402 South Oxfordshire District - South Henley Adwell 27 26 Aston Rowant 665 627 Aston Tirrold 300 295 Aston Upthorpe 144 143 Beckley and Stowood 478 469 Benson 3024 2974 Berinsfield 1869 1849 Berrick Salome 261 254 Binfield Heath 547 535 Bix and Assendon 465 454 Brightwell Baldwin 169 165 Brightwell-cum-Sotwell 1264 1243 Britwell Salome 261 254 Chalgrove 2257 2229 Checkendon 402 399 Chinnor 4677 4833 Clifton Hampden 562 547 Crowell 84 79 Crowmarsh Gifford 1151 1518 Cuddesdon and Denton 396 386 Culham 325 317 Cuxham with Easington 96 93 Dorchester 842 833 Drayton St. Leonard 203 198 East Hagbourne 919 918 Elsfield 80 80 Ewelme 784 778 Eye and Dunsden 250 246 Forest Hill with Shotover 668 654 Garsington 1388 1367 Goring 2674 2650 Goring Heath 959 939 Thame Great Haseley 410 401 Great Milton 581 566 Harpsden 424 -

December 2018 / January 2019 the Editor Writes: to Be Honest, It Has Been a Real Struggle Getting the Magazine Done This Month

The Four Parishes News Magazine BECKLEY FOREST HILL HORTON-cum-STUDLEY STANTON St JOHN 90�� birthday celebration in Stanton St John December 2018 / January 2019 The editor writes: To be honest, it has been a real struggle getting the magazine done this month. The double whammy of a big build up to so many different events on Remembrance Sunday after an incredibly busy October, combined with the need to cover two whole months in this edition of the magazine has not made it any easier! I hope the result will help everyone to get a really clear idea of the many wonderful community events coming up in December and that you will all be inspired to join in as many as possible. Meanwhile, I am delighted to be able to say that we have been working hard on the complicated process of preparing to search for a new vicar and, all being well, the post will be advertised in January. It only remains to wish everyone a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Julia Stutfield Our cover photo … is of George and Olive Lees, and was taken at a tea party in November to celebrate George’s 90�� birthday. George and Olive moved to Stanton St John 40 years ago and they ran the Stanton St John Shop and Post Office for 15 years before retiring in 1993. If you have taken a photo which you think might be suitable for the cover of the next magazine, please email it to [email protected] 2 We welcome contributions or notices for future issues.