Back “Home”: Three Essays on Mexican Return Migrants And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Responsability and Sustainability Report 2020 SA Social Responsability and Sustainability Report 2020

Social Responsability and Sustainability Report 2020 SA Social Responsability and Sustainability Report 2020 Our current circumstances, the extraordinarily complex and uncertain turn of events, leave little room for retrospective analy- sis. Our priority now must be to address both the serious health crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and, at the same time, the resulting profound social and economic crisis that has struck us all so suddenly. All without losing sight of the future. These are times for decisive, rigorous action, for acting with a sense of responsibility and with a long-term view. From the very outset, PRISA, aside from immediately implementing the required sanitary measures, saw its priority as maintain- ing its operations in the areas of quality education, news, culture and entertainment. We are convinced that this was a priority shared by all our target audiences. We have given equal priority to our financial liquidity and the adaptation of our structures, resources and processes to the rapidly changing new environment. Over the past year, the Board of Directors has devoted particular attention to reviewing strategy and to defining the optimum roadmap to ensure that our range of different operations can successfully develop future projects. These must necessarily be transformative – and, by extension, ambitious and exciting – and they must be in a position to generate value on a sustainable basis for all our publics and stakeholders. We also envisage profitability levels that will allow us to offer adequate returns to those who provide us with the necessary re- sources to develop our projects. This unprecedented crisis will have a negative effect on our already high level of indebtedness, which we must reduce and bring within parameters that are appropriate to our businesses. -

Exploring the Relationship Between Militarization in the United States

Exploring the Relationship Between Militarization in the United States and Crime Syndicates in Mexico: A Look at the Legislative Impact on the Pace of Cartel Militarization by Tracy Lynn Maish A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Criminology and Criminal Justice) in the University of Michigan-Dearborn 2021 Master Thesis Committee: Assistant Professor Maya P. Barak, Chair Associate Professor Kevin E. Early Associate Professor Donald E. Shelton Tracy Maish [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8834-4323 © Tracy L. Maish 2021 Acknowledgments The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of their committee and the impact that their guidance had on the process. Without the valuable feedback and enormous patience, this project would not the where it is today. Thank you to Dr. Maya Barak, Dr. Kevin Early, and Dr. Donald Shelton. Your academic mentorship will not be forgotten. ii Table of Contents 1. Acknowledgments ii 2. List of Tables iv 3. List of Figures v 4. Abstract vi 5. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 6. Chapter 2 The Militarization of Law Enforcement Within the United States 8 7. Chapter 3 Cartel Militarization 54 8. Chapter 4 The Look into a Mindset 73 9. Chapter 5 Research Findings 93 10. Chapter 6 Conclusion 108 11. References 112 iii List of Tables Table 1 .......................................................................................................................................... 80 Table 2 ......................................................................................................................................... -

TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO Universidad De Sevilla

TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO Universidad de Sevilla LA SUPERVIVENCIA DEL REALITY GAME COMO FORMATO DE ÉXITO EN ESPAÑA. ESTUDIO DE CASO: OPERACIÓN TRIUNFO Alumno: Ángeles Ceballos Benavides Tutor: Sergio Cobo Durán Curso Académico 2017-2018 Convocatoria de Junio Facultad de Comunicación Grado en Comunicación Audiovisual Indice 1. Justificación…………………………………………………………………………………….3 2. Metodología…………………………………………………………………………………….4 3. Marco teórico y Antecedentes. 3.1. De la televisión tradicional a la televisión social……………………………………………5 3.2. Clasificación de los formatos televisivos…………………………………………………..12 3.3. El origen de los reality game y su desarrollo en América: American Idol como punto de partida……………………………………………………………………………………………20 3.4. La llegada del reality game a España……………………………………………………….23 3.5. Popstar como antecedente del formato de Operación Triunfo……………………………..27 4. Análisis y resultados. 4.1 Recorrido histórico de Operación Triunfo: cambio de cadena y análisis de audiencia……..28 4.2 Comparativa OT1 y OT 2017: concursantes, jurado, academia, galas y chat………………34 4.3 Estrategia transmedia………………………………………………………………………..50 4.4 OT 2017 como revolución televisiva………………………………………………………..54 5. El declive de los programas musicales frente a los reality game………………………………57 6. Conclusiones……………………………………………………………………………………61 7. Bibliografía……………………………………………………………………………………..63 !2 2. Justificación La razón por la que se ha llevado a cabo este trabajo de investigación parte de la premisa de que la televisión es un medio que cada vez se consume menos, sobre todo entre el público joven. Internet está ganando claramente la batalla por el entretenimiento y es por ello que los medios tradicionales buscan desesperadamente la manera de volver a conectar con la audiencia a través de las redes sociales. Sin embargo a veces no es suficiente porque no solo ha cambiado la manera de consumir, sino que los jóvenes pierden cada vez más el interés por los contenidos que se emiten en televisión, especialmente por los que no son de carácter ficcional. -

Federal Register/Vol. 74, No. 249/Wednesday, December 30

Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 249 / Wednesday, December 30, 2009 / Notices 69111 TABLE 1.—DATA ELEMENTS FOR VOLUNTARY PET FOOD REPORTS OF PRODUCT PROBLEMS AND/OR ADVERSE EVENTS SUBMITTED THROUGH THE MEDWATCHPLUS RATIONAL QUESTIONNAIRE SAFETY REPORTING PORTAL—Continued Data Element Description Country This is the country of the veterinary practice where the animal was examined. Street Address Line 1 This is the street address of the veterinary practice where the animal was examined. Street Address Line 2 This is additional street address information for the veterinary prac- tice where the animal was examined (if additional lines are needed to report that information). City/Town This is the city or town of the veterinary practice where the animal was examined. State This is the State of the veterinary practice where the animal was ex- amined. ZIP/Postal Code This is the zip code of the veterinary practice where the animal was examined. E-mail This is the e-mail address of the veterinary practice where the animal was examined. *Primary Phone This is the primary phone number of the veterinary practice where the animal was examined. Attachments Page Attach File *Description of Attachment This requests the reporter provide a brief description of the file being attached, e.g., scanned label or medical records. *Type of Attachment This requests the reporter indicate the specific contents of the attach- ment. * Indicates the information or a response is necessary for FDA to fully process a report. IV. Request for Comments DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND Ahpeahtone, Edwin Paul, University of HUMAN SERVICES Oklahoma, Delaware Nation, FDA invites comments on all aspects Oklahoma. -

Organised Crime and State Sovereignty

Organised Crime and State Sovereignty The conflict between the Mexican state and drug cartels 2006-2011 Jelena Damnjanovic Honours IV 2011 Department of Government and International Relations The University of Sydney Word Count: 19,373 Student ID: 308171594 This work is substantially my own, and where any part of this work is not my own, I have indicated this by acknowledging the source of that part or those parts of the work. Abstract Since December 2006, the government of Mexico has been embroiled in a battle against numerous criminal organisations seeking to control territory and assure continued flow of revenue through the production and trafficking of drugs. Although this struggle has been well documented in Mexican and international media, it has not received as much scholarly attention due to the difficulties involved with assessing current phenomena. This thesis seeks to play a small part in filling that gap by exploring how and why the drug cartels in Mexico have proved a challenge to Mexico’s domestic sovereignty and the state’s capacity to have monopoly over the use of force, maintain effective and legitimate law enforcement, and to exercise control over its territory. The thesis will explain how the violence, corruption and subversion of the state’s authority have resulted in a shift of the dynamics of power from state agents to criminal organizations in Mexico. It also suggests implications for domestic sovereignty in regions experiencing similar problems with organized crime, perhaps pointing to a wider trend in international -

Sonora, Mexico

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development SONORA, MEXICO, Sonora is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico and has made great strides in Sonora, building its human capital and skills. How can Sonora turn the potential of its universities and technological institutions into an active asset for economic and Mexico social development? How can it improve the equity, quality and relevance of education at all levels? Jaana Puukka, Susan Christopherson, This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional Patrick Dubarle, Jocelyne Gacel-Ávila, reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. Sonora, Mexico CONTENTS Chapter 1. Human capital development, labour market and skills Chapter 2. Research, development and innovation Chapter 3. Social, cultural and environmental development Chapter 4. Globalisation and internationalisation Chapter 5. Capacity building for regional development ISBN 978- 92-64-19333-8 89 2013 01 1E1 Higher Education in Regional and City Development: Sonora, Mexico 2013 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

Curso Escolar 2021 / 2022 Lista Provisional De Reserva a Ciclos

Lista provisional de Reserva a Ciclos Formativos de Grado Superior por Título de Técnico de Formación Profesional Curso escolar 2021 / 2022 Centro : CIFP LOS GLADIOLOS (38016519) Estudio: 1º CFGS Dist. Servicios Socioculturales y a la Comunidad - Educación Infantil (LOE) El nº de plazas reservadas para alumnado repetidor o que promociona de un curso inferior es 9 Orden Alumno NIF CIAL Pet. Pre. D.Trab. D.Edad Puntos Cal. 1 Martín González, Inmaculada Concepción ***6625** A81T*****E 1 No 0 14573 0,00 7,90 2 Tafur Baena, Jésica Tatiana ***5212** A92B*****T 2 No 0 10747 0,00 7,83 3 Palmer Fernández, Johanna ***5395** *02B****0F 3 No 0 7094 0,00 7,80 4 Díaz Barrios, Laura Patricia ***2209** **3P**1*3W 3 No 0 13889 0,00 7,64 5 Dannerbauer-Hiyo Geb Hiyo Mendívil, Alexandra ****4276* ***A6**09T 1 No 0 17394 0,00 7,60 6 Díaz García, José Gregorio ***2567** *88L*5***T 4 No 0 11984 0,00 7,54 7 Izquierdo Ríos, Javier ***8136** *97C2****Z 3 No 0 8593 0,00 7,40 8 Angulo Díaz, Yolanda ***6499** *89X6****Z 1 No 0 11790 0,00 7,40 9 Barroso Hernández, Carmen Dolores ***6721** A9*T*7***D 1 No 0 9467 0,00 7,40 10 Díaz Soto, Yaiza Dolores ***7025** ***X67**2B 2 No 0 14710 0,00 7,30 11 Tejera Martín, Tamara ***6568** **9T7*0**X 4 No 0 11635 0,00 7,16 12 Toledo González, María Carolina ***1665** **5G6*1**A 1 No 0 16878 0,00 7,08 13 Rodríguez Yunes, Asier Cristóbal ***7370** A**B1***6D 3 No 0 12200 0,00 7,00 14 Perdomo Romero, Ainara ***1248** B**L6**0*N 2 No 0 7229 0,00 6,69 15 De Salas Tenoury, Verónica ***4629** *9*C**10*G 5 No 0 9344 0,00 6,60 16 Martín -

Regional Arts Council Grants FY 2014

Regional Arts Council grants page 1 FY 2014 - 2015 Individual | Organization FY Funding Grant program ACHF grant City Plan summary source dollars Ada Chamber of Commerce 2014 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $1,000 Ada Fun in the Flatlands artists for 2014 Ada Chamber of Commerce 2015 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $1,300 Ada Fun in the Flatlands Entertainment Argyle American Legion Post 353 2014 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $9,900 Argyle Design and commission two outdoor bronze veterans memorial sculptures Badger Public Schools 2015 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $1,700 Badger Badger Art Club Encampment at North House Folk School City of Kennedy 2014 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $4,200 Kennedy Public art mural painting by Beau Bakken City of Kennedy 2014 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $930 Kennedy Frame and display artistically captured photography throughout time taken in Kennedy, Minnesota City of Kennedy 2015 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $4,100 Kennedy Kennedy Trompe L'Oeil City of Newfolden 2014 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $10,000 Newfolden Commission a bronze sculpture City of Red Lake Falls 2015 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $10,000 Red Lake Falls Red Lake Falls Public Art Awareness Project 2015 City of Roseau 2014 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $2,250 Roseau Artists for Scandinavian Festival East Grand Forks Campbell Library 2014 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $10,000 East Grand Forks Arts presenters in 2014 East Grand Forks Campbell Library 2015 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $10,000 East Grand Forks Engage East Grand Forks 2015 Fosston Community Library and Arts 2014 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $3,000 Fosston Production of The Money in Uncle George's Suitcase Association Fosston Community Library and Arts 2015 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $3,000 Fosston Summer Musical-Swingtime Canteen Association Fosston High School 2015 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $10,000 Fosston Residency with The Copper Street Brass Quintet Friends of Godel Memorial Library 2015 RAC 01 Arts Legacy Grant $9,450 Warren Donor Tree. -

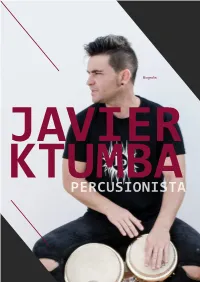

2019 Javier Ktumba

Biografía PERCUSIONISTA Cádiz, España Francisco Javier Mera Rodríguez “Ktumba”, nace en el año 1979 en el castizo barrio del Mentidero, Cádiz, España. A muy temprana edad, comienza a interesarse por el flamenco tocando en grupos de amigos por peñas, fiestas de la ciudad con buenos aficionados, hoy artistas de gran prestigio. 1997-2000 En 1997, se matricula en el Conservatorio Manuel de Falla y estudia hasta el tercer curso de grado elemental. Domina la guitarra, bajo y percusión. En esta última, se ha especializado y ejerce actualmente. Se formó en la escuela de percusión de Londres, la London Samba. Hoy en día sigue formándose en relación a todas las modalidades de percusión que existen para crecer en su profesión. Con 17 años, graba su primer disco con el grupo de Cádiz, “Levantito”, con el que alcanzó varios éxitos en listas, ejerciendo de bajista y haciendo giras por España. Con 19 años graba con “Maíta Vende Cá” y hacen giras por España, consiguiendo su primer disco de platino. En el año 2000, con 21 años de edad, comienza a tocar con el grupo “El Barrio” haciendo giras por España hasta el año 2008, obteniendo varios discos de platino y oro. 3 2001-2010 Mientras estaba de gira con “El Barrio” también acompañó al pianista Manolo Carrasco en su gira por Tokio (Japón) y por China durante 4 meses (2002 y 2004) tocando en teatros de gran prestigio. También cabe destacar la gira realizada con la gran cantaora Montse Cortés por los mejores teatros de España. En el año 2007 realiza una gira por España con el cantaor Jose Mercé, como percusionista actuando en teatros como: Lope de Vega, Gran Teatro Falla, Palau de la Música, Teatro Cervantes entre otros. -

Solicitantes Plaza Escolar

Consejería de Gestión Educativa Educación, Cultura, Deporte y Juventud LISTADO DE SOLICITANTES DE PLAZA ESCOLAR 2021/2022 Nombre Nº Sorteo Proceso 1 Aarab El Moussaoui, Yasmina 1090 Primaria-ESO 2 Abad De la Cruz, Laura 9524 Primaria-ESO 3 Abad Hernández, Wael 2193 Infantil 4 Abad Iglesias, Ana 1106 Primaria-ESO 5 Abad Kultayeva, Darján Javier 4789 Infantil 6 Abadías González, Elisa 3052 Infantil 7 Abadlia , Donia 1309 Infantil 8 Ábalos Alonso, Imanol 6055 Primaria-ESO LisSolEsc.rdf 9 Abaoub Berrouane, Meriem 5509 Infantil 10 Abbas , Haider 8882 Infantil RefDoc. : 11 Abbas , Minahil Fátima 165 Infantil 12 Abdellaoui Bouazzi, Razane 7774 Infantil 13 Abdellaoui Mokrane, Mohammed Amine 613 Primaria-ESO 14 Abdessamie , Marwa 810 Infantil 15 Abed , Tasnim 4794 Infantil 16 Abel García, Diana 5965 Infantil 17 Abellán Jiménez, Mishell 5646 Infantil 18 Abeme Owono, Marcelo 8419 Infantil 19 Abidi , Sohail 7289 Infantil 20 Aboulqlaa Ennafissi, Lamiaa 251 Infantil 21 Ábrego Tofé, Jesús 1589 Primaria-ESO 22 Ábrego Tofé, Marcos 2127 Primaria-ESO 23 Acedo Arnedo, Irene 8485 Primaria-ESO 24 Acevedo Hernández, Christofer Abraham 4504 Infantil 25 Acevedo Mouras, Dara Lucía 1809 Infantil 26 Achancy Troya, Diana Rosalía 250 Infantil 27 Adán Luezas, Andrés 8102 Infantil 28 Adán Martínez, Laura 3221 Primaria-ESO 29 Adán Pérez, Vega 4024 Infantil 30 Adán Ponce de León, Roberto 4593 Primaria-ESO 31 Adán Reinares, Bárbara 3728 Primaria-ESO 32 Adán Sáenz, Jorge 5794 Infantil 33 Adán Sáenz, Juan 9769 Infantil 34 Addahbi , Yusef 8240 Infantil Fecha : 07/05/2021 -

26Barça Operación Triunfo En Palma

Miércoles 22 de octubre de 2003 Mundo Deportivo 26 BARÇA OPERACIÓN TRIUNFO EN PALMA El domingo se “Me gustan enfrentan en Son mucho los dos. Chenoa: ”Son Moix Mallorca y Que gane el Barça, sus dos mejor”, asegura equipos favoritos la cantante Oriol Domènech BARCELONA dad”, explica la cantante, que al entrar en nuestra redacción no du- sentimientos ació en Argentina hace 28 dó en posar ante una imagen del Naños, pero a los ocho se fue 'Pibito'. Precisamente en uno de con su familia a Palma y estos encuentros Chenoa le pidió se siente mallorquina. Y desde ha- un autógrafo al delantero azulgra- ce uno, tras su participación en la na y aún lo tiene pegado en la pa- primera edición del concurso Ope- red de su habitación. ración Triunfo, reside en la Ciu- Aunque ahora también le gusta encontrados” dad Condal. El domingo, en Son el nuevo crack mediático del Ba- Moix, se enfrentarán los dos equi- rça, el brasileño Ronaldinho. Con pos preferidos, el Mallorca y el Ba- quien también coincide es con el rça, de María Laura holandés Michael Rei- Corradini, conocida ziger, ya que son veci- artísticamente como Se declara fan nos. Aunque de todas Chenoa. “No sigo mu- de Javier Saviola, las figuras que han pa- cho el mundo del fút- y del 'Dream sado por el Camp Nou bol pero sí lo suficien- Team' de Johan no tiene ninguna duda te para saber que el en elegir a una: “Hris- domingo hay este par- Cruyff admiró a to Stoichkov”. tido, especial para Hristo Stoichkov mí. -

The Battles for Memory Around The

¡VIVXS LXS QUEREMOS! THE BATTLES FOR MEMORY AROUND THE DISAPPEARED IN MEXICO By María De Vecchi Gerli THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute of the Americas Faculty of Social & Historical Sciences University College London 2018 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I, María De Vecchi Gerli, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis.’ Signed: Date: 10 July 2018 2 DEDICATION To my parents, Milagros Gerli and Bruno De Vecchi, for being an endless source of inspiration, love and support To all those looking for their disappeared loved ones, with my utmost admiration 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my parents Milagros and Bruno. Without their love and support, this thesis would not exist. You are an inspiration. To Mateo, Sarai and Uma, for all the love and happiness they bring. To all the relatives of the disappeared and to the members of human rights organisations who shared their stories with me. More generally, to all those looking for a disappeared loved one and to all those accompanying them in their search for teaching me the most important lessons on love, strength, commitment, and congruence. I want to thank my supervisors, Dr Paulo Drinot and Professor Kevin Middlebrook for their guidance, careful reading and support throughout this project. Thank you both for taking me to the limits and for making this thesis better. Dr Par Engstrom has also been a permanent source of inspiration and support.