A Town Like Alice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soalan No : 93 Pemberitahuan Pertanyaan Dewan Rakyat Mesyuarat Ketiga, Penggal Ketiga Parlimen Keempat Belas Pertanyaan : Bukan

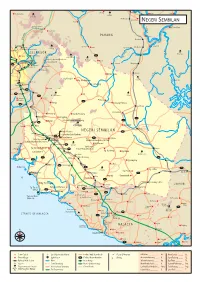

SOALAN NO : 93 PEMBERITAHUAN PERTANYAAN DEWAN RAKYAT MESYUARAT KETIGA, PENGGAL KETIGA PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PERTANYAAN : BUKAN LISAN DARIPADA : TUAN CHA KEE CHIN [RASAH] SOALAN TUAN CHA KEE CHIN [ RASAH ] minta MENTERI KESIHATAN menyatakan senarai jumlah pesakit positif COVID-19 dan kematian akibat jangkitan COVID-19 di Negeri Sembilan mengikut daerah dan mukim. JAWAPAN Tuan Yang di-Pertua, 1. Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia (KKM) ingin memaklumkan sehingga 29 November 2020, kumulatif kes positif COVID-19 yang dilaporkan di Malaysia adalah sebanyak 64,485 kes. Daripada jumlah tersebut, Negeri Sembilan mencatatkan sebanyak 4,774 kes (7.4% daripada keseluruhan kes di Malaysia). Di Negeri Sembilan, kebanyakan kes dilaporkan dari daerah Seremban dan mukim Ampangan. Perincian jumlah kes mengikut daerah dan mukim Negeri Sembilan adalah Seremban (3,973 kes), Rembau (416 kes), Port Dickson (275 kes), Kuala Pilah (34 kes), Tampin (33 kes), Jempol (27 kes) dan Jelebu (16 kes). 2. Pecahan mengikut mukim bagi daerah Seremban adalah seperti berikut: i. Ampangan 1,432 kes; ii. Labu 1,133 kes; iii. Seremban 600 kes; iv. Rantau 358 kes; v. Rasah 277 kes; vi. Setul 151 kes; SOALAN NO : 93 vii. Lenggeng 22 kes; dan viii. Pantai 0 kes. 3. Pecahan mengikut mukim bagi daerah Port Dickson adalah seperti berikut: i. Jimah 110 kes; ii. Si Rusa 135 kes; iii. Port Dickson 19 kes; iv. Linggi 7 kes; dan v. Pasir Panjang 4 kes. 4. Pecahan mengikut mukim bagi daerah Jempol adalah seperti berikut: i. Rompin 8 kes; ii. Kuala jempol 6 kes; iii. Serting Ilir 6 kes; iv. Jelai 5 kes; dan v. Serting ulu 2 kes. -

Negeri Ppd Kod Sekolah Nama Sekolah Alamat Bandar Poskod Telefon Fax Negeri Sembilan Ppd Jempol/Jelebu Nea0025 Smk Dato' Undang

SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH NEGERI SEMBILAN KOD NEGERI PPD NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT BANDAR POSKOD TELEFON FAX SEKOLAH PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA0025 SMK DATO' UNDANG MUSA AL-HAJ KM 2, JALAN PERTANG, KUALA KLAWANG JELEBU 71600 066136225 066138161 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD SMK DATO' UNDANG SYED ALI AL-JUFRI, NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA0026 BT 4 1/2 PERADONG SIMPANG GELAMI KUALA KLAWANG 71600 066136895 066138318 JEMPOL/JELEBU SIMPANG GELAMI PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6001 SMK BAHAU KM 3, JALAN ROMPIN BAHAU 72100 064541232 064542549 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6002 SMK (FELDA) PASOH 2 FELDA PASOH 2 SIMPANG PERTANG 72300 064961185 064962400 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6003 SMK SERI PERPATIH PUSAT BANDAR PALONG 4,5 & 6, GEMAS 73430 064666362 064665711 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6005 SMK (FELDA) PALONG DUA FELDA PALONG 2 GEMAS 73450 064631314 064631173 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6006 SMK (FELDA) LUI BARAT BANDAR SERI JEMPOL 72120 064676300 064676296 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6007 SMK (FELDA) PALONG 7 FELDA PALONG TUJUH GEMAS 73470 064645464 064645588 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6008 SMK (FELDA) BANDAR BARU SERTING BANDAR SERI JEMPOL 72120 064581849 064583115 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6009 SMK SERTING HILIR KOMPLEKS FELDA SERTING HILIR 4 72120 064684504 064683165 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6010 SMK PALONG SEBELAS (FELDA) FELDA PALONG SEBELAS GEMAS 73430 064669751 064669751 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6011 SMK SERI JEMPOL -

MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN NEGERI SEMBILAN D/A Kompleks Jabatan Kebudayaan Dan Kesenian N

MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN NEGERI SEMBILAN d/a Kompleks Jabatan Kebudayaan dan Kesenian N. Sembilan, Taman Budaya Negeri, Jalan Sungai Ujong,70200 Seremban, N.Sembilan Pn. Noridah Nawi MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH TAMPIN D/A Majlis Daerah Tampin, 73009 Tampin, Negeri Pahang, En. Shah Kamruddin b. Hj. Hashim MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH JELEBU D/A Pejabat Daerah dan Tanah Jelebu, 71600 Kuala Klawang, Negeri Sembilan En. Md. Said b. Ahmad MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH PORT DICKSON D/A Majlis Perbandaran Port Dickson, 71009 Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan En. Mohd Hashim b. Md. Taib MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH KUALA PILAH D/A Pejabat Daerah dan Tanah Kuala Pilah, 72000 Kuala Pilah, Negeri Sembilan En. Mohd Nizar b. Abdullah MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH SEREMBAN D/A Pejabat Daerah dan Tanah Seremban, Kompleks Pentadbiran Daerah Persiaran S2 A2, 70300 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan Tn. Hj. Dahlan Hj. Abdullah MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAERAH REMBAU D/A Pejabat Daerah dan tanah Rembau, Kompleks Pentadbiran Daerah Rembau, 71309 rembau, Negeri Sembilan En. Nazri b. Yunus MAJLIS KEBUDAYAAN DAN KESENIAN DAERAH JEMPOL D/A Pejabat daerah dan Tanah jempol, 72120 Bandar Baru Serting, jempol, Negeri Sembilan En. Mazdar b. Abd. Aziz PERSADA STUDIO C-13A, Tingkat 14, Street View, Batu 7, Marina World, Teluk Kemang, 71009 Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan Pn. Sabariah bt. Maarof CITRA BUDAYA, KELAB MELAYU NEGERI SEMBILAN 114,12 ½ Jalan Seremban Kuala Pilah 70400 Seremban Batu 2 ¼, Jalan Kuala Pilah, 70400 Seremban, Negeri Sembilan. En. Mohd Effendi b. Othman D’SETRA JELEBU No.59, Kampung Mengkan, 71600 Kuala Klawang, Negeri Sembilan En. Kamarul b. -

T70 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

T70 bus time schedule & line map T70 Taman Pekan Baru, Titi View In Website Mode The T70 bus line (Taman Pekan Baru, Titi) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Taman Pekan Baru, Titi: 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM (2) Terminal 1 Seremban: 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest T70 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next T70 bus arriving. Direction: Taman Pekan Baru, Titi T70 bus Time Schedule 54 stops Taman Pekan Baru, Titi Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM Monday 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM Terminal 1 Seremban Tuesday 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM Dewan Perbandaran Seremban Wednesday 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM Padang Dewan Perbandaran Seremban Thursday 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM Tasek Mewah Condominium Friday 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM Kompleks Al-Sa'Adah Saturday 6:00 AM - 9:00 PM Pejabat Mara Negeri Seremban Centrepoint Seremban T70 bus Info Mokisq Banana Steakhub Direction: Taman Pekan Baru, Titi Stops: 54 Trip Duration: 90 min Masjid Jamek Dato' Kelana Petra Sendeng Line Summary: Terminal 1 Seremban, Dewan Perbandaran Seremban, Padang Dewan Pak Mok Enterprise Perbandaran Seremban, Tasek Mewah Condominium, Kompleks Al-Sa'Adah, Pejabat Mara Taman Jibol, Seremban Negeri Seremban, Centrepoint Seremban, Mokisq Banana Steakhub, Masjid Jamek Dato' Kelana Petra Kampung Bahagia Ampangan, Seremban Sendeng, Pak Mok Enterprise, Taman Jibol, Seremban, Kampung Bahagia Ampangan, Taman Kayu Manis Fasa Ii, Seremban Seremban, Taman Kayu Manis Fasa Ii, Seremban, Kawasan Perusahaan Pantai, Seremban, Malaysia Kawasan Perusahaan -

Ringer Edwards

Ringer Edwards Ringer Edwards died in 2000-06. 1 person found this useful. How did Edward die? Edward Cullen died from the sickness of the spanish influeza. Share to: How did Edward I die? Edward I . King Edward I of England died in 1307 while travelling to Scotland for a military campaign.. He had been ill for some time and was probably unfit to travel - his â¦cause of death was most likely dysentery. Where did Edward I die? Answer . Ringer Edwards enlisted at Cairns, Queensland on January 21 1941 and was posted to the 2/26th Infantry Battalion. The battalion became part of the 27th Brigade, which was assigned to the 8th Division. Experiences as a POW. Along with many other Allied prisoners, Edwards was sent to work as forced labour on the railway being built by the Japanese army from Thailand to Burma. In 1943, he and two other prisoners killed cattle to provide food for themselves and comrades. Herbert James "Ringer" Edwards was an Australian soldier during World War II. As a prisoner of war , he survived being crucified for 63 hours by Japanese soldiers on the Burma Railway. Edwards was the basis for the character "Joe Harman" in Nevil Shute's novel A Town Like Alice . The book was the basis for a film and a television miniseries . The story behind Edwards's crucifixion began when he and two of his fellow POWs were caught killing cattle for their meat in order to feed themselves and their comrades. The three of them were sentenced to death by crucifixion. -

Negeri Sembilan•State

Lancang Mentakab Ulu Yam Baharu 391 Kg. Ira Cenur 1772 Bt. Woh G. Ulu Kali Ptn. Belengu Temerluh Kg. Tualang Kg. Kertau Karak NEGERI SEMBILAN Genting Highlands g n a Kg. Tebing Tinggi Kg. Bt. Tinggi h a Janda Baik P Bukit Tinggi . g k S a b m P AHANG o Kg. Jelam G . g Mengkarak S ng . Kla Batu Caves Sg Kg. Mengkarak 1493 Sg. Gepoi Gepoi Ptn. Menteri Gombak G. Nuang Kg. Cerang Gombak Orang Asli Centre a r Batu Caves e ng B . 472 ia SELANGOR r g e S Bertangga ga t T Teriang Kuala Ampang an 9 . Setapak . L 1462 g g G. Besar Hantu S S 781 Sungai Chongkak Recreational Forest KUALA LUMPUR Bt. Idung Mancis Jalan Duta Sungai Gabai Waterfalls Mengkuang 111 FEDERAL TERRITORY Kg. Jawi-Jawi Ampang National Zoo Dusun Tua Hulu Langat g Kemayan tin ra Be Be Durian Tipus . g g S S 315 Kg. Kongkoi Senurang S. Besi Kg. Ulu Gelimau Bera Lake Cheras Mines Kg. Temelang Serdang Wonderland Kachau UPM 209 Kajang 210 Kajang 809 Titi 645 1 Bt. Ulu Beranang Palong Tasik Dampar Cyberjaya Semenyih Putrajaya Pertang 86 Beroga Simpang Pertang 212 Bangi Bangi Ayer Hitam Kg. Serting Beranang Kg. Ulu Klawang Batang Benar Lenggeng 10 Forest Reserve Lenggeng 9 Mantin g Nilai 215 n o 1193 l a G. Telapa Buruk P Nilai Batu Kikir . Salak g Bahau S • State Mosque NEGERI SEMBILAN 13 Labu Tiroi • Seremban Lake Gardens Seremban 218 • State Library 51 K. Pilah S State Museum g. SEREMBAN Ulu Bendul Recreational Park M Cultural Handicraft Complex uar Sepang 825 Sri Menanti Port Dickson 219 G. -

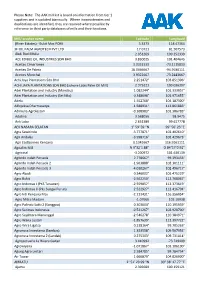

The AAK Mill List Is Based on Information from Tier 1 Suppliers and Is Updated Biannually

Please Note: The AAK mill list is based on information from tier 1 suppliers and is updated biannually. Where inconsistencies and duplications are identified, they are resolved where possible by reference to third party databases of mills and their locations. Mill/ crusher name Latitude Longitude (River Estates) - Bukit Mas POM 5.3373 118.47364 3F OIL PALM AGROTECH PVT LTD 17.0721 81.507573 Abdi Budi Mulia 2.051269 100.252339 ACE EDIBLE OIL INDUSTRIES SDN BHD 3.830025 101.404645 Aceites Cimarrones 3.0352333 -73.1115833 Aceites De Palma 18.0466667 -94.9186111 Aceites Morichal 3.9322667 -73.2443667 Achi Jaya Plantations Sdn Bhd 2.251472° 103.051306° ACHI JAYA PLANTATIONS SDN BHD (Johore Labis Palm Oil Mill) 2.375221 103.036397 Adei Plantation and Industry (Mandau) 1.082244° 101.333057° Adei Plantation and Industry (Sei Nilo) 0.348098° 101.971655° Adela 1.552768° 104.187300° Adhyaksa Dharmasatya -1.588931° 112.861883° Adimulia Agrolestari -0.108983° 101.386783° Adolina 3.568056 98.9475 Aek Loba 2.651389 99.617778 AEK NABARA SELATAN 1° 59' 59 "N 99° 56' 23 "E Agra Sawitindo -3.777871° 102.402610° Agri Andalas -3.998716° 102.429673° Agri Eastborneo Kencana 0.1341667 116.9161111 Agrialim Mill N 9°32´1.88" O 84°17´0.92" Agricinal -3.200972 101.630139 Agrindo Indah Persada 2.778667° 99.393433° Agrindo Indah Persada 2 -1.963888° 102.301111° Agrindo Indah Persada 3 -4.010267° 102.496717° Agro Abadi 0.346002° 101.475229° Agro Bukit -2.562250° 112.768067° Agro Indomas I (PKS Terawan) -2.559857° 112.373619° Agro Indomas II (Pks Sungai Purun) -2.522927° -

NEGERI SEMBILAN P = Parlimen / Parliament N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN)

NEGERI SEMBILAN P = Parlimen / Parliament N = Dewan Undangan Negeri (DUN) KAWASAN / STATE PENYANDANG / INCUMBENT PARTI / PARTY P126 JELEBU ZAINUDIN BIN ISMAIL BN N12601 – CHENNAH LOKE SIEW FOOK DAP N12602 – PERTANG JALALUDDIN BIN ALIAS BN N12603 - SUNGAI LUI MOHD. RAZI BIN MOHD. ALI BN N12604 - KLAWANG YUNUS BIN RAHMAT BN P127 JEMPOL MOHD ISA BIN ABDUL SAMAD BN N12705 – SERTING SHAMSHULKAHAR MOHD DELI BN N12706 – PALONG LILAH BIN YASIN BN N12707 - JERAM PADANG MANICKAM A/L LETCHUMAN BN N12708 - BAHAU CHEW SEH YONG DAP P128 SEREMBAN LOKE SIEW FOOK DAP N12809 – LENGGENG ISHAK BIN ISMAIL BN N12810 – NILAI ARUL KUMAR A/L JAMBUNATHAN DAP N12811 – LOBAK SIOW KIM LEONG DAP N12812 – TEMIANG NG CHIN TSAI DAP N12813 – SIKAMAT AMINUDDIN BIN HARUN PKR N12814 - AMPANGAN ABU UBAIDAH BIN HAJI REDZA BN P129 KUALA PILAH HASAN BIN MALEK BN N12915 - JUASSEH MOHAMMAD RAZI BIN KAIL BN N12916 - SERI MENANTI ABD SAMAD BIN IBRAHIM BN N12917 – SENALING ISMAIL BIN LASIM BN N12918 – PILAH NORHAYATI BINTI OMAR BN N12919 - JOHOL ABU SAMAH BIN MAHAT BN P130 RASAH TEO KOK SEONG DAP N13020 – LABU HASIM BIN RUSDI BN N13021 - BUKIT KEPAYANG CHA KEE CHIN DAP N13022 – RAHANG MARRY JOSEPHINE PRITTAM SINGH DAP N13023 – MAMBAU YAP YEW WENG DAP N13024 - SENAWANG GUNASEKAREN A/L PALASAMY DAP P131 REMBAU KHAIRY JAMALUDDIN ABU BAKAR BN N13125 – PAROI MOHD GHAZALI BIN ABD WAHID BN N13126 – CHEMBONG ZAIFULBAHRI BIN IDRIS BN N13127 – RANTAU MOHAMAD BIN HAJI HASAN BN N13128 - KOTA AWALUDIN BIN SAID BN P132 TELOK KEMAN G KAMARUL BAHARIN BIN ABBAS PKR N13229 – CHUAH CHAI TONG CHAI PKR N13230 – LUKUT EAN YONG TIN SIN DAP N13231 - BAGAN PINANG TUN HAIRUDIN BIN ABU BAKAR BN N13232 – LINGGI ABDUL RAHMAN BIN MOHD REDZA BN N13233 - PORT DICKSON RAVI A/L MUNUSAMY PKR P133 T AMPIN SHAZIMAN BIN ABU MANSOR BN N13334 – GEMAS ABD RAZAK BIN AB SAID BN N13335 – GEMENCHEH MOHD ISAM BIN MOHD ISA BN N13336 - REPAH VEERAPAN A/L SUPERAMANIAM DAP . -

Negeri Sembilan Bil

NEGERI SEMBILAN BIL. NAMA & ALAMAT SYARIKAT NO.TELEFON/FAX JURUSAN ACSAP CORP SDN BHD Tel: 06-6011929 DAGANGAN & 1 NO 58 & 59 JALAN S2 D36,REGENCY AVENUE SEREMBAN 2 CITY Fax: 06-6015936 KHIDMAT CENTRE,70300,SEREMBAN,NEGERI SEMBILAN,DARUL KHUSUS ADVANCE PACT SDN BHD Tel: 06-7652016 DAGANGAN & 2 HOSPITAL TUNKU JAAFAR,JALAN DR MUTHU,70300,SEREMBAN,NEGERI Fax: 06-7652017 KHIDMAT SEMBILAN,DARUL KHUSUS ALIMAN TRAVEL SDN BHD Tel: 06-6013001 3 416 GROUND FLOOR JALAN HARUAN 4,OAKLAND COMMERCIAL TEKNOLOGI Fax: 06-6013001 CENTER,70300,SEREMBAN,NEGERI SEMBILAN,DARUL KHUSUS APEX COMPUTER SERVICES SDN BHD Tel: 03-61877614 4 LOT 2, TINGKAT 2, IT MALL,,TERMINAL 1 SHOPPING CENTRE, JALAN TEKNOLOGI Fax: 03-61877615 LINTANG,70000,SEREMBAN,NEGERI SEMBILAN,DARUL KHUSUS AVILLION ADMIRAL COVE Tel: HOTEL & 5 BATU 5 1/2,JALAN PANTAI,71050,SIRUSA PORT DECKSON,NEGERI Fax: PELANCONGAN SEMBILAN,DARUL KHUSUS AVILLION PORT DICKSON Tel: 06-6476688 HOTEL & 6 BATU 3 JALAN PANTAI,,71000,PORT DICKSON,NEGERI SEMBILAN,DARUL Fax: 06-6464561 PELANCONGAN KHUSUS BABAU TECHNOLOGY SERVICE Tel: 06-4547162 7 NO 20 JALAN MASJID,PUSAT PERNIAGAAN BABAU,72100,BABAU,NEGERI TEKNOLOGI Fax: SEMBILAN,DARUL KHUSUS BAHAGIAN PEMBAHAGIAN TNB Tel: 8 LOT 176, JALAN BESAR,,73000,TAMPIN,NEGERI SEMBILAN,DARUL INFRASTRUKTUR Fax: KHUSUS BAHAGIAN PENJANAAN TNB Tel: 06-6471199 DAGANGAN & 9 SJ TUANKU JA'AFAR,,2600,PORT DICKSON,NEGERI SEMBILAN,DARUL Fax: KHIDMAT KHUSUS BAHAGIAN TEKNOLOGI PENDIDIKAN NEGERI SEMBILAN Tel: 06-6621929 10 KM 14 JALAN PANTAI,TELUK KEMANG,71050,PORT DICKSON,NEGERI TEKNOLOGI Fax: -

Inventory Stations in Negeri Sembilan

INVENTORY STATIONS IN NEGERI SEMBILAN PROJECT STESEN STATION NO STATION NAME FUNCTION STATE DISTRICT RIVER RIVER BASIN YEAR OPEN YEAR CLOSE ISO ACTIVE MANUAL TELEMETRY LOGGER LATITUDE LONGITUDE OWNER ELEV CATCH AREA STN PEDALAMAN 2418034 Politeknik Port Dickson RF Negeri Sembilan Port Dickson Sg. Linggi Linggi 01/12 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE 02 25 40 101 52 15 KG. 82 FALSE 2419054 Ldg. Sengkang RF Negeri Sembilan Port Dickson Sg. Linggi Linggi 01/15 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 02 26 05 101 57 45 Ldg. 83 FALSE 2420052 Ldg. Sg. Bahru RF Negeri Sembilan Rembau Sg. Bahru Linggi 06/33 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 02 28 40 102 05 00 Ldg. 102 FALSE 2420053 Ldg. Bkt. Bertam RF Negeri Sembilan Rembau Sg. Linggi Linggi 06/29 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 02 28 40 102 02 55 Ldg. 93 FALSE 2421001 Titi Bintagor RF Negeri Sembilan Rembau Sg. Rembau Sg. Linggi FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE 02 28 22.9 102 06 0.05 FALSE 2422062 JPS Tampin RF Negeri Sembilan Tampin 01/59 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE 02 28 25 102 13 50 JPS 71 FALSE 2424087 Ldg. Air Tengah RF Negeri Sembilan Tampin Kesang 01/24 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 02 27 55 102 29 00 Ldg. 120 TRUE 2517033 Hospital Port Dickson RF Negeri Sembilan Port Dickson Sg. Lukut Lukut 1891 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE 02 31 50 101 47 50 RS. 64 FALSE 2519046 Ldg. Sua Betong RF Negeri Sembilan Port Dickson Sg. -

Clan Munro Australia

+ Clan Munro Australia Newsletter of the Clan Munro (Association) Australia Volume 5 Issue 3 December 2008 Have you visited our Website at http://clanmunroaustralia.org Chat You may remember me writing about Charles Munroe’s project to transcribe all of RW Munro’s notes into Excel format and to publish them. You will also remember that RW Munro was the Clan Munro historian. That project is now complete and will be included on the CD that Allen Alger produces each year. This is a very exciting addition to Allen’s CD and as I worked on the transcription project, I know that it contains a huge amount of Munro information - I will be very surprised if I do not find some sort of match. Charles assures me that there are a number of Australian & New Zealand references included & has urged us to develop a combined Australia/New Zealand database, so we must get that under This Month way. If you would like your tree to be included in Alan Munro’s data base just let me know and I will tell how to do that. The festive season is on us As in previous years, I will order the CD for all who would like a copy and once again and Bet & I wish distribute them when they arrive. I expect the cost to be about the same as last you all a very merry Christmas year, depending of course on postage, packaging & exchange rate ie about $20.00. & a Happy New Year. Please let me know as soon as possible if you would like to be included on my order list. -

Usp Register

SURUHANJAYA KOMUNIKASI DAN MULTIMEDIA MALAYSIA (MALAYSIAN COMMUNICATIONS AND MULTIMEDIA COMMISSION) USP REGISTER July 2011 NON-CONFIDENTIAL SUMMARIES OF THE APPROVED UNIVERSAL SERVICE PLANS List of Designated Universal Service Providers and Universal Service Targets No. Project Description Remark Detail 1 Telephony To provide collective and individual Total 89 Refer telecommunications access and districts Appendix 1; basic Internet services based on page 5 fixed technology for purpose of widening communications access in rural areas. 2 Community The Community Broadband Centre 251 CBCs Refer Broadband (CBC) programme or “Pusat Jalur operating Appendix 2; Centre (CBC) Lebar Komuniti (PJK)” is an nationwide page 7 initiative to develop and to implement collaborative program that have positive social and economic impact to the communities. CBC serves as a platform for human capital development and capacity building through dissemination of knowledge via means of access to communications services. It also serves the platform for awareness, promotional, marketing and point- of-sales for individual broadband access service. 3 Community Providing Broadband Internet 99 CBLs Refer Broadband access facilities at selected operating Appendix 3; Library (CBL) libraries to support National nationwide page 17 Broadband Plan & human capital development based on Information and Communications Technology (ICT). Page 2 of 98 No. Project Description Remark Detail 4 Mini Community The ultimate goal of Mini CBC is to 121 Mini Refer Broadband ensure that the communities living CBCs Appendix 4; Centre within the Information operating page 21 (Mini CBC) Departments’ surroundings are nationwide connected to the mainstream ICT development that would facilitate the birth of a society knowledgeable in the field of communications, particularly information technology in line with plans and targets identified under the National Broadband Initiatives (NBI).