DISTRIBUTED BY: National Technical Information Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Valley & Highlands

© Lonely Planet Publications 124 lonelyplanet.com ALAJUELA & THE NORTH OF THE VALLEY 125 History exhibit, trout lake and the world’s largest butterfly Central Valley & Of the 20 or so tribes that inhabited pre- enclosure. Hispanic Costa Rica, it is thought that the Monumento National Arqueológico Guayabo Central Valley Huetar Indians were the most ( p160 ) The country’s only significant archaeological site Highlands dominant. But there is very little historical isn’t quite as impressive as anything found in Mexico or evidence from this period, save for the ar- Guatemala, but the rickety outline of forest-encompassed cheological site at Guayabo. Tropical rains villages will still spark your inner Indiana Jones. Parque Nacional Tapantí-Macizo Cerro de la The rolling verdant valleys of Costa Rica’s midlands have traditionally only been witnessed and ruthless colonization have erased most of pre-Columbian Costa Rica from the pages Muerte ( p155 ) This park receives more rainfall than during travelers’ pit stops on their way to the country’s more established destinations. The of history. any other part of the country, so it is full of life. Jaguars, area has always been famous for being one of the globe’s major coffee-growing regions, In 1561 the Spanish pitched their first ocelots and tapirs are some of the more exciting species. CENTRAL VALLEY & and every journey involves twisting and turning through lush swooping terrain with infinite permanent settlement at Garcimuñoz, in Parque Nacional Volcán Irazú ( p151 ) One of the few lookouts on earth that affords views of both the Caribbean HIGHLANDS coffee fields on either side. -

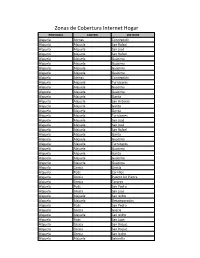

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Horario Y Mapa De La Ruta CARTAGO

Horario y mapa de la línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, CARTAGO - TOBOSI Cartago →Terminal Cartago, Ver En Modo Sitio Web Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias La línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús (Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias) tiene 7 rutas. Sus horas de operación los días laborables regulares son: (1) a Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias: 5:00 - 7:00 (2) a Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias →Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago: 18:20 (3) a Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias →Terminal Quebradilla, Frente A Parque Quebradilla: 8:25 - 21:00 (4) a Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias →Terminal Tobosi, Contiguo A Pollos Charlie: 7:10 (5) a Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias →Terminal Tobosi, Frente A Pollos Charlie: 5:30 - 17:50 (6) a Terminal Tobosi, Contiguo A Pollos Charlie →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias: 5:50 - 20:15 (7) a Terminal Tobosi, Frente A Pollos Charlie →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias: 4:30 - 17:10 Usa la aplicación Moovit para encontrar la parada de la línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús más cercana y descubre cuándo llega la próxima línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús Sentido: Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Horario de la línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús Cartago →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago →Terminal Yglesias Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias Horario de ruta: 35 paradas lunes 5:00 - 7:00 VER HORARIO DE LA LÍNEA martes 5:00 - 7:00 Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago miércoles 5:00 - 7:00 Frente A Escuela Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago jueves 5:00 - 7:00 viernes 5:00 - 7:00 Provisional sábado Sin servicio Frente A Bar & Rest. -

1 074-Drpp-2015

074-DRPP-2015.- DEPARTAMENTO DE REGISTRO DE PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS. San José, a las quince horas cinco minutos del veintiséis de junio de dos mil quince. Acreditación de los nombramientos realizados por el partido Acción Ciudadana en los distritos Paraíso y Llanos de Santa Lucía del cantón Paraíso, Tres Ríos y San Rafael del cantón de La Unión, La Suiza y Tayutic del cantón Turrialba, Pacayas y Cervantes del cantón Alvarado y San Isidro y Tobosi del cantón El Guarco de la provincia de Cartago, en virtud de las renuncias de sus titulares. Mediante resoluciones 033-DRPP-2012 de las ocho horas treinta minutos del cinco de octubre de dos mil doce, 043-DRPP-2012 de las trece horas treinta minutos del once de octubre de dos mil doce, 079-DRPP-2012 de fecha dieciséis de noviembre de dos mil doce, 104-DRPP-2012 de las ocho horas veinte minutos del veintiocho de noviembre de dos mil doce y DGRE- 076-DRPP-2013 de las ocho horas treinta y cinco minutos del doce de julio de dos mil trece, se acreditaron las estructuras internas de los distritos antes mencionados. La agrupación política los días veinticinco y veintiséis de abril, celebró las asambleas distritales en los lugares supra citados, con el fin de nombrar los puestos vacantes, esto en virtud de las renuncias de las personas en los distritos mencionados. CANTÓN PARAÍSO Distrito Paraíso: Mediante oficio DRPP-249-2014, de fecha ocho de agosto del dos mil catorce, este Departamento tomó nota de las renuncias presentadas en oficio PAC-CE- 201-2014 de fecha cuatro de agosto de dos mil catorce y recibido en la Ventanilla Única de Recepción de Documentos de la Dirección General del Registro Electoral y Financiamiento de Partidos Políticos el siete de agosto del mismo año, de los señores Edwin Zúñiga Araya, cédula de identidad 303240671, como tesorero suplente y delegado territorial y Asnet Ivannia Quesada Araya, cédula de identidad 303500582 como delegada territorial, acreditados según resolución 033-DRPP-2012. -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

Geology of the Istaru Quadrangle, Costa Rica

Geology of the IstarU Quadrangle, Costa Rica By RICHARD D. KRUSHENSKY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1 3 5 8 Prepared in cooperation with the 0 ficina de Defensa Civil and the Direccion de Geologza, Minas, y Petr6leo, ",..",..:e::~= Ministerio de Industria y Comercio, under the auspices of the Government of Costa Rica and the Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of State A description of the volcanic deposits surrounding Irazu Volcano, and factors involved in slope stability and landslide control UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretm-y GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Directm· Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600274 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 -Price $1.70 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-00263 CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Location and accessibility of the area ------------------------ 2 Previous work --------------------------------------------- 3 Purpose and method of investigation -------------------------- 4 Acknowledgments ________________ ·--------------------------- 4 Geologic setting of the Istaru quadrangle ------------------------- 5 Stratigraphy --------------------------------------------------- 6 Tertiary System --------------------------------------------- 6 ~iocene Series ----------------------------------------- 6 Terraha Formation -------------------------------- 6 San Miguel Limestone ------------------------------- 8 Goris -

301 Zonashomogeneas Distrito

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 3 CARTAGO CANTÓN 01 CARTAGO DISTRITO 05 AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 506200 511200 516200 521200 a l l i n R e ío r To A y o Mapa de Valores de Terrenos ORIENTAL gr Oreamuno a e i s u OCCIDENTAL q Súper Mas e SAN RAFAEL c A Q GUADALUPE O ARENILLA BARRIO PITAHAYA por Zonas Homogéneas u Antiguo Matadero Municipal e 3 01 05 R03/U03 b Salón comunal r RESIDENCIAL CARTAGO - BARRIO CERRILLOS - SAN LUIS GONZAGA a d R 3 01 05 U04 a ESCUELA PITAHAYA í o Provincia 3 Cartago L MANUEL DE JESUS JIMENEZ u 3 01 05 U02 C æ s 3 01 05 U06 o ia nm r i SANTIAGO s VALLE DEL PRADO - RESIDENCIALnm LAS GARZAS - VEREDAS DEL CONQUISTADOR 3 01 05 U07 Cantón 01 Cartago Avenida 38A CIUDAD DE ORO LLANOS DE SANTA LUCÍA 3 01 05 U27 A 7 o VILLAS DEL SOL - EL CASTILLO r Distrito 05 Aguacaliente o e r l e Teja 3 01 05 U26 l u A a EL TEJAR Cementerio rq C a EscuelaHACIENDA DE ORO HACIENDA REAL B nm ío 3 01 05 U11 3 01 05 U13 San Francisco nm R R 1088400 nm 1088400 COCORI AGUACALIENTE - RESIDENCIAL SAN FRANCISCO í o 3 01 05 U10 nm 3 01 05 U12 JARDINES DE AGUACALIENTE B l a 3 01 05 U24 q u E VALLE VERDE A i A ven TOBOSI A ida 60 l l PARAÍSO T CIUDAD DE LOS NIÑOS 0 o eja LA CAMPIÑA 3 01 05 R14/U14 e r l 3 01 05 U30 3 01 05 R25/U25 l Adepea a 4 enida 6 GUAYABAL Campo de Aterrizaje C Av 3 01 05 U23 nm 2 Presa Q 6 ue Orfanato Salón Comunal b a ra d Hervidero R da i Ruta N n a ciona í G l 231Poblado Barro Morado o ua e v ya A b A a g Llanos de Lourdes FABRICA DE CEMENTO HOLCIM u 3 01 05 R17/U17 a Ministerio de Hacienda C LLANOS DE LOURDES a l i 3 01 05 U16 e n Órgano de Normalización Técnica A San CONDOMINIO EL TEJALæ t Isidro nm e 3 01 05 U29 CACHÍ R BARRO MORADO - NAVARRO ío s C jo 3 01 05 R18/U18 n h ra ir a í N os Guatuso L le al C Cerro Lucosal l Platanillo a j a c s a C a d a r GUATUSO - RIO NAVARRO b to e ri 3 01 05 R19/U19 u r a Q v a N Finca Trinidad ío R Navarrito 1083400 1083400 rro ava Aprobado por: N Q ío Muñeco R u e Iglesia Católica Navarro del Muñeco b r Plaza deæ Deportes a nm d a R o j PEJIBAYE a s Ing. -

Appendix 1. Specimens Examined

Knapp et al. – Appendix 1 – Morelloid Clade in North and Central America and the Caribbean -1 Appendix 1. Specimens examined We list here in traditional format all specimens examined for this treatment from North and Central America and the Caribbean. Countries, major divisions within them (when known), and collectors (by surname) are listed in alphabetic order. 1. Solanum americanum Mill. ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA. Antigua: SW, Blubber Valley, Blubber Valley, 26 Sep 1937, Box, H.E. 1107 (BM, MO); sin. loc. [ex Herb. Hooker], Nicholson, D. s.n. (K); Barbuda: S.E. side of The Lagoon, 16 May 1937, Box, H.E. 649 (BM). BAHAMAS. Man O'War Cay, Abaco region, 8 Dec 1904, Brace, L.J.K. 1580 (F); Great Ragged Island, 24 Dec 1907, Wilson, P. 7832 (K). Andros Island: Conch Sound, 8 May 1890, Northrop, J.I. & Northrop, A.R. 557 (K). Eleuthera: North Eleuthera Airport, Low coppice and disturbed area around terminal and landing strip, 15 Dec 1979, Wunderlin, R.P. et al. 8418 (MO). Inagua: Great Inagua, 12 Mar 1890, Hitchcock, A.S. s.n. (MO); sin. loc, 3 Dec 1890, Hitchcock, A.S. s.n. (F). New Providence: sin. loc, 18 Mar 1878, Brace, L.J.K. 518 (K); Nassau, Union St, 20 Feb 1905, Wight, A.E. 111 (K); Grantstown, 28 May 1909, Wilson, P. 8213 (K). BARBADOS. Moucrieffe (?), St John, Near boiling house, Apr 1940, Goodwing, H.B. 197 (BM). BELIZE. carretera a Belmopan, 1 May 1982, Ramamoorthy, T.P. et al. 3593 (MEXU). Belize: Belize Municipal Airstrip near St. Johns College, Belize City, 21 Feb 1970, Dieckman, L. -

2010 Death Register

Costa Rica National Institute of Statistics and Censuses Department of Continuous Statistics Demographic Statistics Unit 2010 Death Register Study Documentation July 28, 2015 Metadata Production Metadata Producer(s) Olga Martha Araya Umaña (OMAU), INEC, Demographic Statistics Unit Coordinator Production Date July 28, 2012 Version Identification CRI-INEC-DEF 2010 Table of Contents Overview............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Scope & Coverage.............................................................................................................................................. 4 Producers & Sponsors.........................................................................................................................................5 Data Collection....................................................................................................................................................5 Data Processing & Appraisal..............................................................................................................................6 Accessibility........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Rights & Disclaimer........................................................................................................................................... 8 Files Description................................................................................................................................................ -

Mapa Del Cantón De Cartago 01, Distrito 01 a 11

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS 530000 PROVINCIA535000 3 CARTAGO540000 CANTÓN545000 01 CARTAGO550000 ! !! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! CANTÓN!! DE SANTO DOMINGO ! ! ! DISTRITOS DULCE NOMBRE Y SAN FRANCISCO ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! CANTÓN DE VÁZQUEZ DE CORONADO ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! Escala 1:75.000 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! !! ! !! MINISTERIO DE HACIENDA ! ! ! ! 550000 555000 ! 560000 ! ! ! !! ! ! !! !! ! ! 301-09-R28/U28301-09-R28/U28 !! ! ! !! ! !! ! DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE TRIBUTACIÓN ! Hotel Río Perla o !! arr !! av !! N !! ío !! 301-05-R19/U19 R !! PARQUE NACIONAL VOLCÁN IRAZÚ 301-05-R19/U19 !! 301-09-R29/U29 !! 301-09-R29/U29 ! ! CANTÓN DE MORAVIA !!!! !! !! !! !! DIVISIÓN !!! 301-10-R12/U12 Prusia ! 301-10-R12/U12 !! !! !! CANTÓN DE GOICOECHEA Q kæ !! u !!! ! ÓRGANO DE NORMALIZACIÓN TÉCNICA e !! b !! Finca Retes CANTÓN DE TIBÁS ! o ! r !! a R d !! d í !! n a o !! !! o R P !! !! d s o e !! j r e ! e a ! l ! a ! 301-08-R06/U06 n s 301-08-R06/U06 ! R s ! o ! ! Sabanilla !! m i !! o !! L !! h 301-05-R20/U20301-05-R20/U20 CANTÓN DE JIMÉNEZ !! a c !! d !! u Casona n ! s a ! u r ! R ! a r b í !! u !! Alto Llano Verde e o R Y !! u a Fincas a P !! d a !! a Q a Finca Llano Verde r !! t R b 301-10-R11/U11301-10-R11/U11 a í ! ! e r o ! u ! o r !! Q a N d !! la 215000 215000 a !! Finca Brisas Bajas 195000 195000 ZONA PROTECTORA RIO TIRIBI a r !! Qu p a !! e Cañada b -

Fuente Del Enjambre Sísmico De Tobosi Del 2011-2012 En El Centro De Costa Rica

Araya, M. C., Linkimer, L., Montero, W., & Rojas, W. (2015). La falla Tobosi: Fuente del enjambre sísmico de Tobosi del 2011-2012 en el centro de Costa Rica. Revista Geologica de America Central, 53, 89- 102. https://doi.org/10.15517/rgac.v53i0.21145 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC-SA Link to published version (if available): 10.15517/rgac.v53i0.21145 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Revista Geológica de América Central, 53: 89-102, 2015 DOI: 10.15517/rgac.v53i0.21145 ISSN: 0256-7024 THE TOBOSI FAULT: SOURCE OF THE 2011–2012 TOBOSI EARTHQUAKE SWARM IN CENTRAL COSTA RICA LA FALLA TOBOSI: FUENTE DEL ENJAMBRE SÍSMICO DE TOBOSI DEL 2011-2012 EN EL CENTRO DE COSTA RICA María C. Araya*1, 2, Lepolt Linkimer1, 2, Walter Montero3 & Wilfredo Rojas1, 2 1Red Sismológica Nacional (RSN: UCR-ICE), Apdo. 214-2060, San Pedro, Costa Rica 2Escuela Centroamericana de Geología, Universidad de Costa Rica 3Centro de Investigaciones Geológicas, Universidad de Costa Rica *Corresponding author: [email protected] (Recibido: 22/08/2014; aceptado: 08/06/2015) ABSTRACT: The Central Costa Rica Deformed Belt (CCRDB) is an ~100-km broad zone of deformation that marks the boundary between the Caribbean Plate and the Panama Microplate. -

Discrepancias Entre Uso Actual Y Potencial De Las Laderas Del Valle De Orosi

Rev. Reflexiones 87 (2): 91-110, ISSN: 1021-1209 / 2008 DISCREPANCIAS ENTRE USO ACTUAL Y POTENCIAL DE LAS LADERAS DEL VALLE DE OROSI Víctor Ml. Cortés Granados* [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 1º de setiembre 2008 - Fecha de aceptación: 10 de octubre 2008 Resumen El área de estudio tiene una extensión de 92 km2, localizada en la cuenca del Río Grande de Orosi, con lluvias que varían entre los 1665 y 6287 mm. Esta zona está comprendida, entre las localidades de Purisil, Orosi, Ujarrás y Cachí. El uso actual de la tierra es en un 48 % bosque, 21 % café, 17 % pastos y el resto pequeñas parcelas de cultivos anuales (tomate, chile, papa, etc.), cultivos perennes (chayote, caña de azúcar, cítricos, etc.), embalses, uso urbano y tierras misceláneas. Está dominada por pendi- entes entre 15 y más de 75 %, o sea por las clases de capacidad de uso de la tierra VI, VII y VIII, las cuales comprenden el 73 %, del total de clases presentes en la zona de estudio; esto quiere decir que las laderas del Valle de Orosi son de vocación agrícola restringida, principalmente para uso forestal. Abstract Studied area corresponds to 92 km2, located at the Río Grande de Orosi basin, which anual precipita- tion goes from 1665 mm to 6287. This región includes the localites of Purisil, Orosi, Ujarrás and Cachí. Current usage of this land is 48 % forest, 21 % coffee plantings 17 % pasture grounds and rest is destined to small plot of anual crops (tomato, pepper, patato, among others), perennial crops (chayote, sugar cane and citrus), dams, housing and miscellaneous activities.