Chapter 9 Integration on Rn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boundedness in Linear Topological Spaces

BOUNDEDNESS IN LINEAR TOPOLOGICAL SPACES BY S. SIMONS Introduction. Throughout this paper we use the symbol X for a (real or complex) linear space, and the symbol F to represent the basic field in question. We write R+ for the set of positive (i.e., ^ 0) real numbers. We use the term linear topological space with its usual meaning (not necessarily Tx), but we exclude the case where the space has the indiscrete topology (see [1, 3.3, pp. 123-127]). A linear topological space is said to be a locally bounded space if there is a bounded neighbourhood of 0—which comes to the same thing as saying that there is a neighbourhood U of 0 such that the sets {(1/n) U} (n = 1,2,—) form a base at 0. In §1 we give a necessary and sufficient condition, in terms of invariant pseudo- metrics, for a linear topological space to be locally bounded. In §2 we discuss the relationship of our results with other results known on the subject. In §3 we introduce two ways of classifying the locally bounded spaces into types in such a way that each type contains exactly one of the F spaces (0 < p ^ 1), and show that these two methods of classification turn out to be identical. Also in §3 we prove a metrization theorem for locally bounded spaces, which is related to the normal metrization theorem for uniform spaces, but which uses a different induction procedure. In §4 we introduce a large class of linear topological spaces which includes the locally convex spaces and the locally bounded spaces, and for which one of the more important results on boundedness in locally convex spaces is valid. -

Symmetric Rigidity for Circle Endomorphisms with Bounded Geometry

SYMMETRIC RIGIDITY FOR CIRCLE ENDOMORPHISMS WITH BOUNDED GEOMETRY JOHN ADAMSKI, YUNCHUN HU, YUNPING JIANG, AND ZHE WANG Abstract. Let f and g be two circle endomorphisms of degree d ≥ 2 such that each has bounded geometry, preserves the Lebesgue measure, and fixes 1. Let h fixing 1 be the topological conjugacy from f to g. That is, h ◦ f = g ◦ h. We prove that h is a symmetric circle homeomorphism if and only if h = Id. Many other rigidity results in circle dynamics follow from this very general symmetric rigidity result. 1. Introduction A remarkable result in geometry is the so-called Mostow rigidity theorem. This result assures that two closed hyperbolic 3-manifolds are isometrically equivalent if they are homeomorphically equivalent [18]. A closed hyperbolic 3-manifold can be viewed as the quotient space of a Kleinian group acting on the open unit ball in the 3-Euclidean space. So a homeomorphic equivalence between two closed hyperbolic 3-manifolds can be lifted to a homeomorphism of the open unit ball preserving group actions. The homeomorphism can be extended to the boundary of the open unit ball as a boundary map. The boundary is the Riemann sphere and the boundary map is a quasi-conformal homeomorphism. A quasi-conformal homeomorphism of the Riemann 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary: 37E10, 37A05; Secondary: 30C62, 60G42. Key words and phrases. quasisymmetric circle homeomorphism, symmetric cir- arXiv:2101.06870v1 [math.DS] 18 Jan 2021 cle homeomorphism, circle endomorphism with bounded geometry preserving the Lebesgue measure, uniformly quasisymmetric circle endomorphism preserving the Lebesgue measure, martingales. -

Generalizations of the Riemann Integral: an Investigation of the Henstock Integral

Generalizations of the Riemann Integral: An Investigation of the Henstock Integral Jonathan Wells May 15, 2011 Abstract The Henstock integral, a generalization of the Riemann integral that makes use of the δ-fine tagged partition, is studied. We first consider Lebesgue’s Criterion for Riemann Integrability, which states that a func- tion is Riemann integrable if and only if it is bounded and continuous almost everywhere, before investigating several theoretical shortcomings of the Riemann integral. Despite the inverse relationship between integra- tion and differentiation given by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, we find that not every derivative is Riemann integrable. We also find that the strong condition of uniform convergence must be applied to guarantee that the limit of a sequence of Riemann integrable functions remains in- tegrable. However, by slightly altering the way that tagged partitions are formed, we are able to construct a definition for the integral that allows for the integration of a much wider class of functions. We investigate sev- eral properties of this generalized Riemann integral. We also demonstrate that every derivative is Henstock integrable, and that the much looser requirements of the Monotone Convergence Theorem guarantee that the limit of a sequence of Henstock integrable functions is integrable. This paper is written without the use of Lebesgue measure theory. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Patrick Keef and Professor Russell Gordon for their advice and guidance through this project. I would also like to acknowledge Kathryn Barich and Kailey Bolles for their assistance in the editing process. Introduction As the workhorse of modern analysis, the integral is without question one of the most familiar pieces of the calculus sequence. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Lecture 15-16 : Riemann Integration Integration Is Concerned with the Problem of finding the Area of a Region Under a Curve

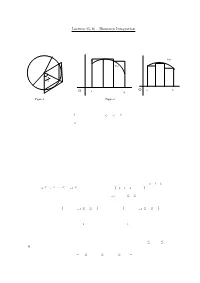

1 Lecture 15-16 : Riemann Integration Integration is concerned with the problem of ¯nding the area of a region under a curve. Let us start with a simple problem : Find the area A of the region enclosed by a circle of radius r. For an arbitrary n, consider the n equal inscribed and superscibed triangles as shown in Figure 1. f(x) f(x) π 2 n O a b O a b Figure 1 Figure 2 Since A is between the total areas of the inscribed and superscribed triangles, we have nr2sin(¼=n)cos(¼=n) · A · nr2tan(¼=n): By sandwich theorem, A = ¼r2: We will use this idea to de¯ne and evaluate the area of the region under a graph of a function. Suppose f is a non-negative function de¯ned on the interval [a; b]: We ¯rst subdivide the interval into a ¯nite number of subintervals. Then we squeeze the area of the region under the graph of f between the areas of the inscribed and superscribed rectangles constructed over the subintervals as shown in Figure 2. If the total areas of the inscribed and superscribed rectangles converge to the same limit as we make the partition of [a; b] ¯ner and ¯ner then the area of the region under the graph of f can be de¯ned as this limit and f is said to be integrable. Let us de¯ne whatever has been explained above formally. The Riemann Integral Let [a; b] be a given interval. A partition P of [a; b] is a ¯nite set of points x0; x1; x2; : : : ; xn such that a = x0 · x1 · ¢ ¢ ¢ · xn¡1 · xn = b. -

1 Definition

Math 125B, Winter 2015. Multidimensional integration: definitions and main theorems 1 Definition A(closed) rectangle R ⊆ Rn is a set of the form R = [a1; b1] × · · · × [an; bn] = f(x1; : : : ; xn): a1 ≤ x1 ≤ b1; : : : ; an ≤ x1 ≤ bng: Here ak ≤ bk, for k = 1; : : : ; n. The (n-dimensional) volume of R is Vol(R) = Voln(R) = (b1 − a1) ··· (bn − an): We say that the rectangle is nondegenerate if Vol(R) > 0. A partition P of R is induced by partition of each of the n intervals in each dimension. We identify the partition with the resulting set of closed subrectangles of R. Assume R ⊆ Rn and f : R ! R is a bounded function. Then we define upper sum of f with respect to a partition P, and upper integral of f on R, X Z U(f; P) = sup f · Vol(B); (U) f = inf U(f; P); P B2P B R and analogously lower sum of f with respect to a partition P, and lower integral of f on R, X Z L(f; P) = inf f · Vol(B); (L) f = sup L(f; P): B P B2P R R R RWe callR f integrable on R if (U) R f = (L) R f and in this case denote the common value by R f = R f(x) dx. As in one-dimensional case, f is integrable on R if and only if Cauchy condition is satisfied. The Cauchy condition states that, for every ϵ > 0, there exists a partition P so that U(f; P) − L(f; P) < ϵ. -

Bounded Holomorphic Functions of Several Variables

Bounded holomorphic functions of several variables Gunnar Berg Introduction A characteristic property of holomorphic functions, in one as well as in several variables, is that they are about as "rigid" as one can demand, without being iden- tically constant. An example of this rigidity is the fact that every holomorphic function element, or germ of a holomorphic function, has associated with it a unique domain, the maximal domain to which the function can be continued. Usually this domain is no longer in euclidean space (a "schlicht" domain), but lies over euclidean space as a many-sheeted Riemann domain. It is now natural to ask whether, given a domain, there is a holomorphic func- tion for which it is the domain of existence, and for domains in the complex plane this is always the case. This is a consequence of the Weierstrass product theorem (cf. [13] p. 15). In higher dimensions, however, the situation is different, and the domains of existence, usually called domains of holomorphy, form a proper sub- class of the class of aU domains, which can be characterised in various ways (holo- morphic convexity, pseudoconvexity etc.). To obtain a complete theory it is also in this case necessary to consider many-sheeted domains, since it may well happen that the maximal domain to which all functions in a given domain can be continued is no longer "schlicht". It is possible to go further than this, and ask for quantitative refinements of various kinds, such as: is every domain of holomorphy the domain of existence of a function which satisfies some given growth condition? Certain results in this direction have been obtained (cf. -

A Representation of Partially Ordered Preferences Teddy Seidenfeld

A Representation of Partially Ordered Preferences Teddy Seidenfeld; Mark J. Schervish; Joseph B. Kadane The Annals of Statistics, Vol. 23, No. 6. (Dec., 1995), pp. 2168-2217. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0090-5364%28199512%2923%3A6%3C2168%3AAROPOP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C The Annals of Statistics is currently published by Institute of Mathematical Statistics. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ims.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Tue Mar 4 10:44:11 2008 The Annals of Statistics 1995, Vol. -

An Analytic Exact Form of the Unit Step Function

Mathematics and Statistics 2(7): 235-237, 2014 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ms.2014.020702 An Analytic Exact Form of the Unit Step Function J. Venetis Section of Mechanics, Faculty of Applied Mathematics and Physical Sciences, National Technical University of Athens *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2014 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract In this paper, the author obtains an analytic Meanwhile, there are many smooth analytic exact form of the unit step function, which is also known as approximations to the unit step function as it can be seen in Heaviside function and constitutes a fundamental concept of the literature [4,5,6]. Besides, Sullivan et al [7] obtained a the Operational Calculus. Particularly, this function is linear algebraic approximation to this function by means of a equivalently expressed in a closed form as the summation of linear combination of exponential functions. two inverse trigonometric functions. The novelty of this However, the majority of all these approaches lead to work is that the exact representation which is proposed here closed – form representations consisting of non - elementary is not performed in terms of non – elementary special special functions, e.g. Logistic function, Hyperfunction, or functions, e.g. Dirac delta function or Error function and Error function and also most of its algebraic exact forms are also is neither the limit of a function, nor the limit of a expressed in terms generalized integrals or infinitesimal sequence of functions with point wise or uniform terms, something that complicates the related computational convergence. Therefore it may be much more appropriate in procedures. -

Notes on Metric Spaces

Notes on Metric Spaces These notes introduce the concept of a metric space, which will be an essential notion throughout this course and in others that follow. Some of this material is contained in optional sections of the book, but I will assume none of that and start from scratch. Still, you should check the corresponding sections in the book for a possibly different point of view on a few things. The main idea to have in mind is that a metric space is some kind of generalization of R in the sense that it is some kind of \space" which has a notion of \distance". Having such a \distance" function will allow us to phrase many concepts from real analysis|such as the notions of convergence and continuity|in a more general setting, which (somewhat) surprisingly makes many things actually easier to understand. Metric Spaces Definition 1. A metric on a set X is a function d : X × X ! R such that • d(x; y) ≥ 0 for all x; y 2 X; moreover, d(x; y) = 0 if and only if x = y, • d(x; y) = d(y; x) for all x; y 2 X, and • d(x; y) ≤ d(x; z) + d(z; y) for all x; y; z 2 X. A metric space is a set X together with a metric d on it, and we will use the notation (X; d) for a metric space. Often, if the metric d is clear from context, we will simply denote the metric space (X; d) by X itself. -

Compact and Totally Bounded Metric Spaces

Appendix A Compact and Totally Bounded Metric Spaces Definition A.0.1 (Diameter of a set) The diameter of a subset E in a metric space (X, d) is the quantity diam(E) = sup d(x, y). x,y∈E ♦ Definition A.0.2 (Bounded and totally bounded sets)A subset E in a metric space (X, d) is said to be 1. bounded, if there exists a number M such that E ⊆ B(x, M) for every x ∈ E, where B(x, M) is the ball centred at x of radius M. Equivalently, d(x1, x2) ≤ M for every x1, x2 ∈ E and some M ∈ R; > { ,..., } 2. totally bounded, if for any 0 there exists a finite subset x1 xn of X ( , ) = ,..., = such that the (open or closed) balls B xi , i 1 n cover E, i.e. E n ( , ) i=1 B xi . ♦ Clearly a set is bounded if its diameter is finite. We will see later that a bounded set may not be totally bounded. Now we prove the converse is always true. Proposition A.0.1 (Total boundedness implies boundedness) In a metric space (X, d) any totally bounded set E is bounded. Proof Total boundedness means we may choose = 1 and find A ={x1,...,xn} in X such that for every x ∈ E © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive 429 license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 S. Gentili, Measure, Integration and a Primer on Probability Theory, UNITEXT 125, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54940-4 430 Appendix A: Compact and Totally Bounded Metric Spaces inf d(xi , x) ≤ 1. -

Chapter 7. Complete Metric Spaces and Function Spaces

43. Complete Metric Spaces 1 Chapter 7. Complete Metric Spaces and Function Spaces Note. Recall from your Analysis 1 (MATH 4217/5217) class that the real numbers R are a “complete ordered field” (in fact, up to isomorphism there is only one such structure; see my online notes at http://faculty.etsu.edu/gardnerr/4217/ notes/1-3.pdf). The Axiom of Completeness in this setting requires that ev- ery set of real numbers with an upper bound have a least upper bound. But this idea (which dates from the mid 19th century and the work of Richard Dedekind) depends on the ordering of R (as evidenced by the use of the terms “upper” and “least”). In a metric space, there is no such ordering and so the completeness idea (which is fundamental to all of analysis) must be dealt with in an alternate way. Munkres makes a nice comment on page 263 declaring that“completeness is a metric property rather than a topological one.” Section 43. Complete Metric Spaces Note. In this section, we define Cauchy sequences and use them to define complete- ness. The motivation for these ideas comes from the fact that a sequence of real numbers is Cauchy if and only if it is convergent (see my online notes for Analysis 1 [MATH 4217/5217] http://faculty.etsu.edu/gardnerr/4217/notes/2-3.pdf; notice Exercise 2.3.13). 43. Complete Metric Spaces 2 Definition. Let (X, d) be a metric space. A sequence (xn) of points of X is a Cauchy sequence on (X, d) if for all ε > 0 there is N N such that if m, n N ∈ ≥ then d(xn, xm) < ε.