Trinidad & Tobago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20190430, Unrevised Senate Debate

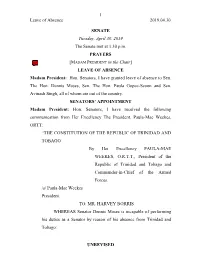

1 Leave of Absence 2019.04.30 SENATE Tuesday, April 30, 2019 The Senate met at 1.30 p.m. PRAYERS [MADAM PRESIDENT in the Chair] LEAVE OF ABSENCE Madam President: Hon. Senators, I have granted leave of absence to Sen. The Hon. Dennis Moses, Sen. The Hon. Paula Gopee-Scoon and Sen. Avinash Singh, all of whom are out of the country. SENATORS’ APPOINTMENT Madam President: Hon. Senators, I have received the following communication from Her Excellency The President, Paula-Mae Weekes, ORTT: “THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO By Her Excellency PAULA-MAE WEEKES, O.R.T.T., President of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. /s/ Paula-Mae Weekes President. TO: MR. HARVEY BORRIS WHEREAS Senator Dennis Moses is incapable of performing his duties as a Senator by reason of his absence from Trinidad and Tobago: UNREVISED 2 Senators’ Appointment (cont’d) 2019.04.30 NOW, THEREFORE, I, PAULA-MAE WEEKES, President as aforesaid, acting in accordance with the advice of the Prime Minister, in exercise of the power vested in me by section 44(1)(a) and section 44(4)(a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, do hereby appoint you, HARVEY BORRIS, to be temporarily a member of the Senate, with effect from 30th April, 2019 and continuing during the absence from Trinidad and Tobago of the said Senator Dennis Moses. Given under my Hand and the Seal of the President of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago at the Office of the President, St. -

20010629, House Debates

29 Ombudsman Report Friday, June 29, 2001 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, June 29, 2001 The House met at 1.30 p.m. PRAYERS [MR. SPEAKER in the Chair] OMBUDSMAN REPORT (TWENTY-THIRD) Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, I have received the 23rd Annual Report of the Ombudsman for the period January 01, 2000—December 31, 2000. The report is laid on the table of the House. CONDOLENCES (Mr. Tahir Kassim Ali) Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, it is disheartening that I announce the passing of a former representative of this honourable House, Mr. Tahir Kassim Ali. I wish to extend condolences to the bereaved family. Members of both sides of the House may wish to offer condolences to the family. The Attorney General and Minister of Legal Affairs (Hon. Ramesh Lawrence Maharaj): Mr. Speaker, the deceased, Mr. Tahir Ali served this Parliament from the period 1971—1976. He was the elected Member of Parliament for Couva. He resided in the constituency of Couva South. In addition to being a Member of Parliament, he was also a Councillor for the Couva electoral district in the Caroni County Council for the period 1968—1971. He served as Member of Parliament and Councillor as a member of the People’s National Movement. In 1974 he deputized for the hon. Shamshuddin Mohammed, now deceased, as Minister of Public Utilities for a period of time. In 1991, Mr. Tahir Ali assisted the United National Congress in the constituency of Couva South for the general election of that year. He would be remembered as a person who saw the light and came to the United National Congress. -

1 the REPUBLIC of TRINIDAD and TOBAGO in the HIGH COURT of JUSTICE Claim No. CV2008-02265 BETWEEN BASDEO PANDAY OMA PANDAY Claim

THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE Claim No. CV2008-02265 BETWEEN BASDEO PANDAY OMA PANDAY Claimants AND HER WORSHIP MS. EJENNY ESPINET Defendant AND DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS Interested Party Before the Honorable Mr. Justice V. Kokaram Appearances: Mr. G. Robertson Q.C., Mr. R. Rajcoomar and Mr. A. Beharrylal instructed by Ms. M. Panday for the Claimants Mr. N. Byam for Her Worship Ms. Ejenny Espinet Mr. D. Mendes, S.C. and Mr. I. Benjamin instructed by Ms. R. Maharaj for the Interested Party 1 JUDGMENT 1. Introduction: 1.1 Mr. Basdeo Panday (“the first Claimant”) is one of the veterans in the political life of Trinidad and Tobago. He is the political leader of the United National Congress Alliance (“UNC-A”), the member of Parliament for the constituency of Couva North in the House of Representatives, the Leader of the Opposition in the Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago and former Prime Minister of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago 1. He has been a member of the House of Representatives since 1976 and in 1991 founded the United National congress (“UNC”) the predecessor to the UNC-A. He together with his wife, Oma Panday (“the second Claimant”) were both charged with the indictable offence of having committed an offence under the Prevention of Corruption Act No. 11 of 1987 namely: that on or about 30 th December 1998, they corruptly received from Ishwar Galbaransingh and Carlos John, an advantage in the sum of GBP 25,000 as a reward on account for the first Claimant, for favouring the interests of Northern Construction Limited in relation to the construction of the then new Piarco International Airport 2. -

Trinidad and Tobago

Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Overall risk level High Reconsider travel Can be dangerous and may present unexpected security risks Travel is possible, but there is a potential for disruptions Overview Emergency Numbers Medical 811 Upcoming Events There are no upcoming events scheduled Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 / Trinidad and Tobago 2 Travel Advisories Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 / Trinidad and Tobago 3 Summary Trinidad and Tobago is a High Risk destination: reconsider travel. High Risk locations can be dangerous and may present unexpected security risks. Travel is possible, but there is a potential for severe or widespread disruptions. Covid-19 High Risk A steep uptick in infections reported as part of a second wave in April-June prompted authorities to reimpose restrictions on movement and business operations. Infection rates are increasing again since July. International travel remains limited to vaccinated travellers only. Political Instability Low Risk A parliamentary democracy led by centrist Prime Minister Keith Rowley, Trinidad and Tobago's democracy is firmly entrenched thanks to a well-established system of checks and balances that helped it remain resilient in the face of sources of instability like politically motivated murders in 1980 and an Islamist coup attempt in 1990. Despite its status as a regional and economic leader in the Caribbean, the nation faces challenges of corruption allegations in the highest level of government and an extensive drug trade and associated crime that affects locals and tourists alike. Conflict Low Risk Trinidad and Tobago has been engaged in a long-standing, and at times confrontational, dispute over fishing rights with Barbados that also encompasses other resources like oil and gas. -

Full Text (PDF)

International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 13-35 ISSN: 2333-6021 (Print), 2333-603X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijgws.v2n3a2 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijgws.v2n3a2 Challenges to Women’s Leadership in Ex-Colonial Societies Ann Marie Bissessar1 Abstract Women have held key leadership positions since the year 3000 BCE. Indeed, one of the earliest Egyptian queens, Ku-baba, ruled in the Mesopotamian City-State of UR around 2500 BCE. However, this trend to place females in key leadership roles did not emerge in the Western World until during World War I when women took on the role as members of the revolutionary governments in countries such Ukraine, Russia, Hungary, and Ireland. By the 1960s there were to be further gains as Sirivamo Bandaranaike of Sri Lanka became the world's first female President and in 1974 Isabel Perón of Argentina also assumed a leadership position. Today, there are approximately twenty nine female leaders in twenty nine different countries. Eleven of these female Presidents are in the countries of Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Finland, India, Kosovo, Kyrgystan, Liberia, Lithuania, San Marino and Switzerland. In addition there are three reigning queens in the countries of Denmark, The Netherlands and The United Kingdom. Twelve females also serve as Prime Ministers in the countries of Australia, Bangladesh, Croatia, Germany, Iceland, Mali, Slovakia, Thailand, and Trinidad and Tobago and in the self-governing territories of Bermuda, Saint Maartin and the Åland Islands. -

Trinidad and Tobago Parliamentary Elections

Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 7 September 2015 Map Trinidad and Tobago Parliamentary Elections 7 September 2015 Table of Contents LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL .................................................................................... iv CHAPTER 1 ............................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Terms of Reference ............................................................................................ 1 Activities .............................................................................................................. 2 CHAPTER 2 ............................................................................................................... 3 Political Background ............................................................................................... 3 Early History ........................................................................................................ 3 Transition to independence ................................................................................. 3 Post-Independence Elections.............................................................................. 4 Context for the 2015 Parliamentary Elections ..................................................... 5 CHAPTER 3 .............................................................................................................. -

Religion and the Alter-Nationalist Politics of Diaspora in an Era of Postcolonial Multiculturalism

RELIGION AND THE ALTER-NATIONALIST POLITICS OF DIASPORA IN AN ERA OF POSTCOLONIAL MULTICULTURALISM (chapter six) “There can be no Mother India … no Mother Africa … no Mother England … no Mother China … and no Mother Syria or Mother Lebanon. A nation, like an individual, can have only one Mother. The only Mother we recognize is Mother Trinidad and Tobago, and Mother cannot discriminate between her children. All must be equal in her eyes. And no possible interference can be tolerated by any country outside in our family relations and domestic quarrels, no matter what it has contributed and when to the population that is today the people of Trinidad and Tobago.” - Dr. Eric Williams (1962), in his Conclusion to The History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, published in conjunction with National Independence in 1962 “Many in the society, fearful of taking the logical step of seeking to create a culture out of the best of our ancestral cultures, have advocated rather that we forget that ancestral root and create something entirely new. But that is impossible since we all came here firmly rooted in the cultures from which we derive. And to simply say that there must be no Mother India or no Mother Africa is to show a sad lack of understanding of what cultural evolution is all about.” - Dr. Brinsley Samaroo (Express Newspaper, 18 October 1987), in the wake of victory of the National Alliance for Reconstruction in December 1986, after thirty years of governance by the People’s National Movement of Eric Williams Having documented and analyzed the maritime colonial transfer and “glocal” transculturation of subaltern African and Hindu spiritisms in the southern Caribbean (see Robertson 1995 on “glocalization”), this chapter now turns to the question of why each tradition has undergone an inverse political trajectory in the postcolonial era. -

Multiculturalism and the Challenge of Managing Diversity in Trinidad and Tobago

Journal of Social Science for Policy Implications March 2014, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 127-149 ISSN: 2334-2900 (Print), 2334-2919 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Multiculturalism and the Challenge of Managing Diversity in Trinidad and Tobago Indira Rampersad1 Abstract As one of the most cosmopolitan islands of the Caribbean, Trinidad and Tobago is among the few developing countries and the first Caribbean state to move towards an official multiculturalism policy. This paper examines the challenges faced by the island in its attempts to manage diversity through an exploration of the dense interconnections between the cultural and the political processes which have informed such debates in the country throughout history. It details the efforts at initiating a multicultural policy for Trinidad and Tobago and contends that the cultural and the political are intricately intertwined and are integral to the discourse on multiculturalism and assimilationism in the country. However, the political and social debates whether via music, symposia, media or commentary, suggest that there is no concrete position on the merits of an official multiculturalism policy. Nonetheless, these have undoubtedly informed the discourse, thoughts and ideas on the issue. Keywords: Multiculturalism; assimilationism; Trinidad and Tobago; political; cultural; Indians; Africans Introduction Multiculturalism as a discourse emerged in the post-colonial period. Stuart Hall noted that “with the dismantling of the old empires, many new multi-ethnic and multi-cultural nation-states were created. 1 PhD, Department of Behavioural Sciences, The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago, , Email: [email protected] 128 Journal of Social Science for Policy Implications, Vol. -

From Grassroots to the Airwaves Paying for Political Parties And

FROM GRASSROOTS TO THE AIRWAVES: Paying for Political Parties and Campaigns in the Caribbean OAS Inter-American Forum on Political Parties Editors Steven Griner Daniel Zovatto Published by Organization of American States (OAS) International IDEA Washington, D.C. 2005 © Organization of American States (OAS) © International IDEA First Edition, August, 2005 1,000 copies Washinton, D.C. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Organization of American States or the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Editors: Steven Griner Daniel Zovatto ISBN 0-8270-7856-4 Layout by: Compudiseño - Guatemala, C.A. Printed by: Impresos Nítidos - Guatemala, C.A. September, 2005. Acknowledgements This publication is the result of a joint effort by the Office for the Promotion of Democracy of the Organization of American States, and by International IDEA under the framework of the Inter-American Forum on Political Parties. The Inter-American Forum on Political Parties was established in 2001 to fulfill the mandates of the Inter-American Democratic Charter and the Summit of the Americas related to the strengthening and modernization of political parties. In both instruments, the Heads of State and Government noted with concern the high cost of elections and called for work to be done in this field. This study attempts to address this concern. The overall objective of this study was to provide a comparative analysis of the 34 member states of the OAS, assessing not only the normative framework of political party and campaign financing, but also how legislation is actually put into practice. -

Basdeo Panday Leader of the United National Congress

STRONG LEADERSHIP FOR A STRONG T&T THE UNITED NATIONAL CONGRESS Re s t o r i n g Tru s t he PNM’s unrelenting seven-year campaign and its savagely partisan Tuse of the apparatus of the State to humiliate and criminalise the leadership and prominent supporters of the UNC have failed to produce a single convic- tion on any charge of misconduct in public office. The UNC nonetheless recognises the compelling obligation to move immedi- ately with speed and purpose to do all that is possible to restore the public trust. We will therefore lose no time and spare an individual of manifestly impeccable no effort in initiating the most stringent reputation and sterling character, charged measures that will enforce on all persons with the responsibility of igniting in gov- holding positions of public trust, scrupu- ernment and in the wider national com- lous compliance with the comprehensive munity of the Republic of Trinidad and legislative and legal sanctions that the Tobago, a culture of transparency, UNC has already introduced, and will yet accountability, decency, honesty, and formulate, to ensure unwavering adher- probity, that will permit no compromise, ence to the highest ethical standards and will protect no interest save the public the most exacting demands of probity in good, and will define the politics of this all matters of Governance. nation into perpetuity. To these ends, we will appoint as Minister of Public Administration and Compliance, Basdeo Panday Leader of the United National Congress 1 THE UNITED NATIONAL CONGRESS STRONG LEADERSHIP -

Elections, Identity and Ethnic Conflict in the Caribbean the Trinidad Case

Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe Revue du CRPLC 14 | 2004 Identité et politique dans la Caraïbe insulaire Elections, Identity and Ethnic Conflict in the Caribbean The Trinidad Case Ralph R. Premdas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/plc/246 DOI: 10.4000/plc.246 ISSN: 2117-5209 Publisher L’Harmattan Printed version Date of publication: 14 January 2004 Number of pages: 17-61 ISBN: 2-7475-7061-4 ISSN: 1279-8657 Electronic reference Ralph R. Premdas, « Elections, Identity and Ethnic Conflict in the Caribbean », Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe [Online], 14 | 2004, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/plc/246 ; DOI : 10.4000/plc.246 © Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe ELECTIONS, IDENTITY AND ETHNIC CONFLICT IN THE CARIBBEAN: THE TRINIDAD CASE by Ralph R. PREMDAS Department of Government University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Below the surface of Trinidad's political peace exists an antagonistic ethnic monster waiting its moment of opportunity to explode!. The image of a politically stable and economically prosperous state however conceals powerful internal contradictions in the society. Many critical tensions prowl through the body politic threatening to throw the society into turmoil. Perhaps, the most salient of these tensions derives from the country's multi-ethnic population. Among the one million, two hundred thousand citizens live four distinct ethno-racial groups: Africans, Asian Indians, Europeans and Chinese. For two centuries, these groups co-existed in Trinidad, but failed to evolve a consensus of shared values so as to engender a sense of common citizenship and a shared identity. -

Historical Disjunctures and Bollywood Audiences in Trinidad: Negotiations of Gender and Ethnic Relations in Cinema Going1

. Volume 16, Issue 2 November 2019 Historical disjunctures and Bollywood audiences in Trinidad: Negotiations of gender 1 and ethnic relations in cinema going Hanna Klien-Thomas Oxford Brookes University, UK Abstract: Hindi cinema has formed an integral part of the media landscape in Trinidad. Audiences have primarily consisted of the descendants of indentured workers from India. Recent changes in production, distribution and consumption related to the emergence of the Bollywood culture industry have led to disruptions in the local reception context, resulting in a decline in cinema-going as well as the diminishing role of Hindi film as ethnic identity marker. This paper presents results of ethnographic research conducted at the release of the blockbuster ‘Jab Tak Hai Jaan’. It focuses on young women’s experiences as members of a ‘new’ Bollywood audience, characterised by a regionally defined middle class belonging and related consumption practices. In order to understand how the disjuncture is negotiated by contemporary audiences, cinema-going as a cultural practice is historically contextualised with a focus on the dynamic interdependencies of gender and ethnicity. Keywords: Hindi cinema, Caribbean, Bollywood, Indo-Trinidadian identity, Indian diaspora, female audiences, ethnicity Introduction Since the early days of cinema, Indian film productions have circulated globally, establishing transnational and transcultural audiences. In the Caribbean, first screenings are reported from the 1930s. Due to colonial labour regimes, large Indian diasporic communities existed in the region, who embraced the films as a connection to their country of origin or ancestral homeland. Consequently, Hindi speaking films and more recently the products of the global culture industry Bollywood, have become integral parts of regional media landscapes.