UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starlog Magazine Issue

23 YEARS EXPLORING SCIENCE FICTION ^ GOLDFINGER s Jjr . Golden Girl: Tests RicklBerfnanJponders Er_ her mettle MimilMif-lM ]puTtism!i?i ff?™ § m I rifbrm The Mail Service Hold Mail Authorization Please stop mail for: Name Date to Stop Mail Address A. B. Please resume normal Please stop mail until I return. [~J I | undelivered delivery, and deliver all held I will pick up all here. mail. mail, on the date written Date to Resume Delivery Customer Signature Official Use Only Date Received Lot Number Clerk Delivery Route Number Carrier If option A is selected please fill out below: Date to Resume Delivery of Mail Note to Carrier: All undelivered mail has been picked up. Official Signature Only COMPLIMENTS OF THE STAR OCEAN GAME DEVEL0PER5. YOU'RE GOING TO BE AWHILE. bad there's Too no "indefinite date" box to check an impact on the course of the game. on those post office forms. Since you have no Even your emotions determine the fate of your idea when you'll be returning. Everything you do in this journey. You may choose to be romantically linked with game will have an impact on the way the journey ends. another character, or you may choose to remain friends. If it ever does. But no matter what, it will affect your path. And more You start on a quest that begins at the edge of the seriously, if a friend dies in battle, you'll feel incredible universe. And ends -well, that's entirely up to you. Every rage that will cause you to fight with even more furious single person you _ combat moves. -

Inside: Events, Calendar, Movies & Much More!

August - October 2021 Inside: Events, Calendar, Movies & Much More! SEE ALL THAT KINGS POINT HAS TO OFFER! NEWS & REVUES Published by Vesta Property Services Events Sun., August 1 Event Start Time Event Start Time MONACO BALLROOM FREE MOVIE "THE PERFECT STORM" 1:15 PM SEWING ROOM KNITTING CLUB 1:00 PM SOCIAL ROOM RUSSIAN ROOTS - ENTHUSIASTS GRP 3:00 PM SOCIAL ROOM RUSSIAN ROOTS CLUB- NASTALGIA 3:00 PM FLANDERS MAIN PARKING LOT ONE STEP AT A TIME 7:00 PM MAIN CARD ROOM CANASTA KINGS, QUEENS & JOKERS 7:00 PM SOCIAL ROOM SOCIABLES 7:00 PM Mon., August 2 Event Start Time WEST PARKING MAIN CLBHSE ONE STEP AT A TIME 7:00 PM ART ROOM ART WORKSHOP 9:00 AM GRAND BALLROOM/KINGS HALL TWENTY/TWENTY/TWENTY CLASS 9:00 AM Fri., August 6 MONACO BALLROOM K.P.C.A MEETING 9:30 AM CLASS ROOM ASG MANAGEMENT 8:00 AM CERAMICS ROOM CERAMICS - MONDAYS - AM 10:00 AM GRAND BALLROOM/KINGS HALL TAI CHI CLASS 9:15 AM INDOOR POOL WATER FIT & PILATES 10:00 AM INDOOR POOL WATER AEROBICS 10:00 AM SEWING ROOM TEDDIES FOR TOTS 10:00 AM GRAND BALLROOM/KINGS HALL TOTAL BODY FITNESS 10:30 AM CLASS ROOM ASSOCIA PROPERTY MANAGEMENT 10:30 AM MAIN CLUBHOUSE POOL POP-UP BBQ 11:00 AM GRAND BALLROOM/KINGS HALL CHAIR FIT - MONDAYS 10:30 AM SOCIAL ROOM RUSSIAN CLUB - MUSICAL GROUP 11:00 AM CERAMICS ROOM CERAMICS - MONDAYS - PM 1:00 PM GRAND BALLROOM/KINGS HALL HERMANS BRIDGE CLUB 12:30 PM MEDIA ROOM I.C.A. -

STEVEN WOLFF Production Designer Wolffsteven.Com

STEVEN WOLFF Production Designer wolffsteven.com PROJECTS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS THE PURGE Various Directors Alissa Kantrow / Blumhouse Television Season 2 USA THE FINEST Regina King Linda Berman, Pam Veasey Pilot Lincoln Square Productions / ABC TAKEN Various Directors Lena Cordina, Matthew Gross, Greg Plageman Season 2 Universal TV / NBC ONCE UPON A TIME Various Directors Edward Kitsis, Adam Horowitz, Steve Pearlman Season 5-6 Kathy Gilroy / Disney / ABC GRIMM Various Directors Jim Kouf, David Greenwalt, Norberto Barba Season 2-6 Steve Oster / NBC RINGER Various Directors Pam Veasey, Eric Charmelo, Nicole Snyder Season 1 CBS GCB Alan Poul Darren Star, Alan Poul, Rob Harling Pilot ABC BODY OF PROOF Various Directors Matt Gross, Christopher Murphy Season 1-2 ABC DEADLY HONEYMOON Paul Shapiro Stanton W. Kamens, Angela Laprete MOW Lifetime / Island Film Group DARK BLUE Various Directors Jerry Bruckheimer, Danny Cannon, Kelly Van Horn Season 1 - 5 Episodes TNT DIRTY SEXY MONEY Various Directors Greg Berlanti, Craig Wright, Matt Gross Season 1-2 ABC / Berlanti Television 52 FIGHTS Luke Greenfield Alex Taub, Peter Traugott MOW ABC WATERFRONT Ed Bianchi Jack Orman, Peter R. McIntosh, Gregori J. Martin Series Warner Bros. / CBS RELATED Various Directors Marta Kauffman, Steve Pearlman Season 1 Warner Bros. DR. VEGAS Various Directors Jack Orman / Warner Bros. Season 1 CBS BOSTON PUBLIC Various Directors David E. Kelley / Fox Series FREAKYLINKS Various Directors David Simkins / Fox Season 1 GET REAL Various Directors Clyde Phillips / Fox Season 1 ACTION Ted Demme Chris Thompson, Robert Lloyd Lewis Pilot Fox PARTY OF FIVE Various Directors Amy Lippman, Chris Keyser / Fox Season 1 PLAYERS Various Directros Dick Wolf / NBC Season 1 TALES FROM THE CRYPT Various Directors Joel Silver, Dick Donner, David Giler, Walter Hill Season 1 HBO SLEDGE HAMMER! Various Directors Alan Spencer, Thomas John Kane Season 1 ABC . -

Newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 212 - September 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/07 (Nr. 212) September 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, schen und japanischen DVDs Aus- Nach den in diesem Jahr bereits liebe Filmfreunde! schau halten, dann dürfen Sie sich absolvierten Filmfestivals Es gibt Tage, da wünscht man sich, schon auf die Ausgaben 213 und ”Widescreen Weekend” (Bradford), mit mindestens fünf Armen und 214 freuen. Diese werden wir so ”Bollywood and Beyond” (Stutt- mehr als nur zwei Hirnhälften ge- bald wie möglich publizieren. Lei- gart) und ”Fantasy Filmfest” (Stutt- boren zu sein. Denn das würde die der erfordert das Einpflegen neuer gart) steht am ersten Oktober- tägliche Arbeit sicherlich wesent- Titel in unsere Datenbank gerade wochenende das vierte Highlight lich einfacher machen. Als enthu- bei deutschen DVDs sehr viel mehr am Festivalhimmel an. Nunmehr siastischer Filmfanatiker vermutet Zeit als bei Übersee-Releases. Und bereits zum dritten Mal lädt die man natürlich schon lange, dass Sie können sich kaum vorstellen, Schauburg in Karlsruhe zum irgendwo auf der Welt in einem was sich seit Beginn unserer Som- ”Todd-AO Filmfestival” in die ba- kleinen, total unauffälligen Labor merpause alles angesammelt hat! dische Hauptstadt ein. Das diesjäh- inmitten einer Wüstenlandschaft Man merkt deutlich, dass wir uns rige Programm wurde gerade eben bereits mit genmanipulierten Men- bereits auf das Herbst- und Winter- offiziell verkündet und das wollen schen experimentiert wird, die ge- geschäft zubewegen. -

On the Auto Body, Inc

FINAL-1 Sat, Oct 14, 2017 7:52:52 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of October 21 - 27, 2017 HARTNETT’S ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3 ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 10/31/17 BUMPER SPECIALISTSHartnetts H1artnett x 5” On the Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 run DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 Emma Dumont stars 15 WATER STREET in “The Gifted” DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Now that their mutant abilities have been revealed, teenage siblings must go on the lam in a new episode of “The Gifted,” airing Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 Monday. ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents Massachusetts’ First Credit Union • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks St. Jean's Credit Union • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3” With 35 years experience on the North Serving over 15,000 Members •3 A Partx 3 of your Community since 1910 Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs The LawOffice of Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI Auto • Homeowners 978.739.4898 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M. -

STEVEN WOLFF Production Designer

STEVEN WOLFF Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS THE PURGE Season 2 -10 episodes Various Directors Blumhouse Production THE FINEST Pilot Regina King Linda Berman, Pam Veasey Lincoln Square Productions / ABC TAKEN Season 2 Various Directors Lena Cordina, Matthew Gross, Greg Plageman Universal TV / NBC ONCE UPON A TIME Season 5-6 Various Directors Edward Kitsis, Adam Horowitz, Steve Pearlman Kathy Gilroy / Disney / ABC GRIMM Season 2-6 Various Directors Jim Kouf, David Greenwalt, Norberto Barba Steve Oster / NBC RINGER Season 1 Various Directors Pam Veasey, Eric Charmelo, Nicole Snyder CBS GCB Pilot Alan Poul Darren Star, Alan Poul, Rob Harling / ABC BODY OF PROOF Season 1-2 Various Directors Matt Gross, Christopher Murphy / ABC DEADLY HONEYMOON MOW Paul Shapiro Stanton W. Kamens, Angela Laprete Lifetime / Island Film Group DARK BLUE Season 1 - 5 Episodes Various Directors Jerry Bruckheimer, Danny Cannon, Kelly Van Horn TNT DIRTY SEXY MONEY Season 1-2 Various Directors Greg Berlanti, Craig Wright, Matt Gross ABC / Berlanti Television 52 FIGHTS MOW Luke Greenfield Alex Taub, Peter Traugott / ABC WATERFRONT Series Ed Bianchi Jack Orman, Peter R. McIntosh, Gregori J. Martin Warner Bros. / CBS RELATED Season 1 Various Directors Marta Kauffman, Steve Pearlman / Warner Bros. DR. VEGAS Season 1 Various Directors Jack Orman / Warner Bros. / CBS BOSTON PUBLIC Series Various Directors David E. Kelley / Fox FREAKYLINKS Season 1 Various Directors David Simkins / Fox GET REAL Season 1 Various Directors Clyde Phillips / Fox ACTION Pilot Ted Demme Chris Thompson, Robert Lloyd Lewis / Fox PARTY OF FIVE Season 1 Various Directors Amy Lippman, Chris Keyser / Fox PLAYERS Season 1 Various Directros Dick Wolf / NBC TALES FROM THE CRYPT Season 1 Various Directors Joel Silver, Dick Donner, David Giler, Walter Hill / HBO SLEDGE HAMMER! Season 1 Various Directors Alan Spencer, Thomas John Kane / ABC . -

Engineering (Mail Stop No

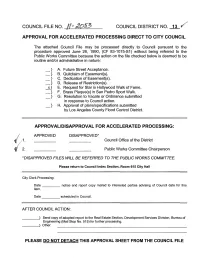

COUNCIL FILE NO. /f- t20S3 COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 fl"'/ APPROVAl FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCil The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1075-S1) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: _} A. Future Street Acceptance. _} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). _} C. Dedication of Easement(s). _} D. Release of Restriction(s). _15] E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. _} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. _} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. _} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAl/DISAPPROVAl FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* /,1. Council Office of the District '/ 2. Public Works Committee Chairperson *DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: ____~ Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. ____~ Other: PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCil FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS- E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council DEC 0 7 2011 Ofthe City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C. -

Oleandro Bianco)

MEDIAFILM Presenta ALISON LOHMAN ROBIN WRIGHT PENN MICHELLE PFEIFFER RENÉE ZELLWEGER (Oleandro Bianco) Regia di PETER KOSMINSKY Prodotto da JOHN WELLS HUNT LOWRY Sceneggiatura di MARY AGNES DONOGHUE Tratto dal romanzo di JANET FITCH edito in Italia da Il Saggiatore Produttori esecutivi KRISTIN HARMS, STACY COHEN, E.K. GAYLORD II, PATRICK MARKEY Scenografie di DONALD GRAHAM BURT Montaggio di CHRIS RIDSDALE Musiche di THOMAS NEWMAN durata: 110 minuti il film su internet: www.mediafilm.it foto e pressbook in formato digitale: www.image.net UFFICIO STAMPA STUDIO MORABITO Tel. 06 57300825 Fax 06 57300155 [email protected] data di uscita: 31 gennaio 2003 2 OLEANDRO NOME SCIENTIFICO Nerium oleander FAMIGLIA Apocynaceae Noto ai greci ed ai Romani per la sua velenosità Portamento E' un arbusto cespuglioso che talvolta ha portamento arboreo sviluppandosi in alberi non più alti di 8 m. La corteccia dei fusti e dei rami più giovani è di colore verde che, poi, con l'età diventa di un color grigio cenere. Le foglie, di colore verde grigio, sono molto coriacee e sono caratterizzate da una forma lanceolata che termina con un apice acuto. Fiori e frutti La fioritura dell'oleandro è piuttosto tardiva e si manifesta da giugno a settembre. I fiori sono molto grandi e vistosi e sono riuniti in ciuffi. Il colore è variabile e va dal bianco al rosa pallido e dal rosa intenso al rosso. I frutti sono delle capsule brune, simili a stretti legumi, lunghe fino a 15 cm che contengono numerosi semi con un apice munito di lunghi peli rossastri. Distribuzione e caratteristiche E' un albero diffuso in tutto il Mediterraneo e nel Medio Oriente dove predilige gli alvei dei corsi d'acqua. -

Sweet Home Alabama's Reese Witherspoon Talks About

COVER 8/9/02 1:56 PM Page x2 canada’s #1 movie magazine in canada’s #1 theatres 3/C B G september 2002 | volume 3 | number 9 R 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 ABANDON’S BENJAMIN BRATT MOVES ON * SPOTLIGHT ON: JAMES FRANCO 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 & KATE HUDSON * FALL FASHION WITH JEANNE BEKER Sweet Home Alabama’s Reese Witherspoon talks about finding success on and off the screen 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 $3.00 SALMA HAYEK AND GILLIAN ANDERSON FANTASIZE ABOUT SCREENMATES PL2060_Famous_Reason1.qxd 8/12/02 3:43 PM Page 1 Reason #1: The price. Now only $299* *MSRP. "PlayStation" and the "PS" Family logo are registered trademarks of Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. Horizontal stand not included. 716860-SK 1pg Ad pre-street 8/12/02 11:52 AM Page 1 as this year’s biggest, extreme, non-stop action event. Featuring WWF sensation, “THE ROCK”. The Scorpion King takes you on an extreme adventure featuring mind-blowing action sequences and larger than life battles. You will be fighting to own this intense DVD or Video that continues the epic Mummy series! • Extended Version in Enhanced Viewing Mode VHS A unique opportunity to see alternate versions of key scenes in the movie $ 25.95 DVD • Live Footage from “The Rock’s” Feature Commentary S.R.P. $34.95 • Outtakes and Alternate Versions of Key Scenes S.R.P. • The Fight Scenes The process of shooting a fight sequence • Universal Studios Total Axess Revolutionary DVD-ROM experience that contains exclusive added value and behind-the-scenes footage • Godsmack Music Video “I Stand Alone” CD Soundtrack featuring 3 new “live” songs by multi-platinum artists GODSMACK, plus other hits by: • P.O.D. -

Network Telivision

NETWORK TELIVISION NETWORK SHOWS: ABC AMERICAN HOUSEWIFE Comedy ABC Studios Kapital Entertainment Wednesdays, 9:30 - 10:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Katy Mixon as Katie Otto, Meg Donnelly as Taylor Otto, Diedrich Bader as Jeff Otto, Ali Wong as Doris, Julia Butters as Anna-Kat Otto, Daniel DiMaggio as Harrison Otto, Carly Hughes as Angela Executive producers: Sarah Dunn, Aaron Kaplan, Rick Weiner, Kenny Schwartz, Ruben Fleischer Casting: Brett Greenstein, Collin Daniel, Greenstein/Daniel Casting, 1030 Cole Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038 Shoots in Los Angeles. BLACK-ISH Comedy ABC Studios Tuesdays, 9:00 - 9:30 p.m., returns Oct. 3 Cast: Anthony Anderson as Andre “Dre” Johnson, Tracee Ellis Ross as Rainbow Johnson, Yara Shahidi as Zoey Johnson, Marcus Scribner as Andre Johnson, Jr., Miles Brown as Jack Johnson, Marsai Martin as Diane Johnson, Laurence Fishburne as Pops, and Peter Mackenzie as Mr. Stevens Executive producers: Kenya Barris, Stacy Traub, Anthony Anderson, Laurence Fishburne, Helen Sugland, E. Brian Dobbins, Corey Nickerson Casting: Alexis Frank Koczaraand Christine Smith Shevchenko, Koczara/Shevchenko Casting, Disney Lot, 500 S. Buena Vista St., Shorts Bldg. 147, Burbank, CA 91521 Shoots in Los Angeles DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Drama ABC Studios The Mark Gordon Company Wednesdays, 10:00 - 11:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Kiefer Sutherland as Tom Kirkman, Natascha McElhone as Alex Kirkman, Adan Canto as Aaron Shore, Italia Ricci as Emily Rhodes, LaMonica Garrett as Mike Ritter, Kal Pennas Seth Wright, Maggie Q as Hannah Wells, Zoe McLellan as Kendra Daynes, Ben Lawson as Damian Rennett, and Paulo Costanzo as Lyor Boone Executive producers: David Guggenheim, Simon Kinberg, Mark Gordon, Keith Eisner, Jeff Melvoin, Nick Pepper, Suzan Bymel, Aditya Sood, Kiefer Sutherland Casting: Liz Dean, Ulrich/Dawson/Kritzer Casting, 4705 Laurel Canyon Blvd., Ste. -

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues.