The Alarm Has Sounded. a Descriptive Study of Performance Measures Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Hospital Emergency Medical Care Study

MANAGEMENT ADVISORY GROUP, INC. MANAGEMENT CONSULTING SERVICES Pre-Hospital Emergency Medical Care Study For Travis County, Texas November 4, 2011 PRE -HOSPITAL EMERGENCY MEDICAL CARE STUDY for Travis County, Texas NOVEMBER 4, 2011 MANAGEMENT ADVISORY GROUP , INC . Virginia/DC Area Headquarters 4000 Genesee Place, Suite 205 Lake Ridge, Virginia 22192 Phone: 703.590.7250 Fax: 703.590.0366 Management Advisory Group, Inc. Emergency Medical Care Study MANAGEMENT ADVISORY GROUP, INC. LOCAL GOVERNMENT CONSULTING SERVICES November 4, 2011 Mr. Danny Hobby County Executive, Emergency Services Travis County Dear Mr. Hobby, Please find enclosed a report for the study of pre-hospital emergency medical care (RFS # S110093-EC). We are pleased to have had the opportunity to assist you and the County in this important project. We would like to thank all of the participants in this study. They include County management and staff, ATCEMS management and staff, municipal managers, ESD’s at all levels, and informed and interested citizens who have shared their ideas. MAG’s study team is offering 37 specific recommendations in response to the goals of the original Request for Services. Please feel free to call or email at any time as we move forward in the review of the report. Sincerely, Donald C. Long, Ph.D. Executive Vice President Management Advisory Group, Inc. 4000 Genesee Place, Suite 205 Lake Ridge, VA 22192 (703) 590-7250 or (828) 808-3551 cell [email protected] TRAVIS COUNTY, TEXAS STUDY OF PRE-HOSPITAL EMERGENCY CARE FOR TRAVIS COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary Table of Contents Section 1.0 – Scope of Work .......................................................................... -

Appendix B – Fire Department Communications

NIOSH Firefighter Radio Communications APPENDIX B: FIRE DEPARTMENT COMMUNICATIONS – EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD The information contained in this appendix was gathered from a variety of sources. Much of the information comes from fire department management studies previously undertaken by TriData Corporation. Some information comes from individual fire department annual reports, websites, or other fire department literature. Wherever possible, the information from these studies was verified with the fire department to ensure that the most current data was reflected in this report. TABLE 1: EXPERIENCES FROM THE FIELD – DEPARTMENT OVERVIEW Resident Land Land Fire Population Area1 Area Department Uniformed Communications Jurisdiction 13 (sq. mi) Protected Type Employees System Austin, TX 656,562 252 Urban Career 979 UHF (450 MHz) Urban/ Bellingham, WA 67,171 32 Career 140 VHF Suburban UHF (483-MHz Boston, MA 589,141 48 Urban Career 1,600 Conventional) Boulder, CO Rural Suburban/ 8 FTE; VHF 18,000 25 Combination Fire Department Rural 35 Volunteer (153–155-MHz) Suburban/ 9 FTE; UHF (400/800 MHz Brighton, CO 20,905 17 Combination Rural 60 Volunteers Trunked) UHF (800 MHz Charlotte, NC 540,828 242 Urban Career 890 Trunked) Chicago, IL 2,896,016 227 Urban Career 4,000 VHF (Conventional) Urban/ 1,300 Career; UHF (800 MHz Clark County, NV 1,375,675 8,000 Combination 14 Rural 400 Volunteer Trunked) Dallas, TX 1,188,580 385 Urban Career 1,700 UHF (400 MHz) Detroit, MI 951,270 139 Urban Career 1,296 UHF (400 MHz) Urban/ Everett, WA 91,488 48 Career -

Fire Safety in the Changing Urban Landscape

Fire Safety in the Changing Urban Landscape Carl D. Wren, P.E. Austin Fire Department Emergency Prevention Division Austin, Texas New Urbanism & The Fire Service • November 2007 - CNU initiated contact with fire service personnel to request a dialog about fire code provisions impacting street design. • Interest in dialogue concerning street design and emergency vehicle access • Rocky Start – distrust, battle wounds, project disappointments, real or imagined slights • Though not extensive as in 2008 and 2009, hopefully the dialogue is continuing. New Urbanism & The Fire Service • New Urbanism has several goals and this list is not comprehensive and is not intended to imply representation of this interest group. These points are based on the presenter’s understanding of New Urbanism and its goals. • Reduced street widths in order to create more walkable, bike friendly, and sustainable communities. • Reduction in the pace of urban expansion by creating greater density in urban cores. New Urbanism & The Fire Service • Reductions in, or limiting of the creation of new, impervious cover within existing and new developments. • Reduced traffic speeds with improvements in traffic pattern effectiveness by the design and use of narrower street sections along with improvements in connectivity. • Maintaining or improving fire and life safety by reducing traffic injuries and deaths along with improving in-situ fire safety features. New Urbanism & The Fire Service • Communications is essential in working with developers and planners desiring to use new urbanist community design techniques. • Apparatus turning radii need to be accounted for in new street designs and restructuring of existing streets. • Mixing new urbanist approaches with that used in traditional neighborhood development can cause problems – narrow streets without adequate turning radii and/or connectivity. -

December Meeting

The Hyde Park December Neighborhood E P A R Y D K Meeting Association H . When: 7:00 p.m. PPecanecan Monday, December 4, 2006 Where: Hyde Park United Meth od ist Church 4001 Speedway Who: YOU and your neighbors Note: HPNA general meetings usually take place on the fi rst Monday of each month. Press December, 2006 • National Register District Neighborhood • Vol. 32, No. 12 HPNA General Meeting Agenda for December 4th ‘Tis the Season! Helping Hands - Presentation on charitable opportunities with Helping Hands Home for Children Fire Safety in Your Home - Presentation by Tim La Fuente of Austin Fire Department Public Education Office Mueller Project - Discussion with Matt Whelan HPNA Budget - Official vote to be taken Hyde Park Holidays Party December 15 • 6:00-7:30 p.m. at Woodburn House B&B Front Porch of Woodburn House yde Park Holidays Party will be held Friday, HDecember 15 from 6:00 to 7:30 p.m. at the Woodburn House Bed & Breakfast, 4401 Avenue D. The HPNA invites you to come and share your own special holiday spirit with other neighbors. The offi cers and leaders of the Association and the gracious owners of the Woodburn House, Kristen and Noel De La Rosa, will be on hand to greet you. This year’s festivities will be Deli, and an extra treat from Pascal even more fun than last year’s, if Nicolas- one of the new owners of YOU are there! Bring your own Dolce Vita. Judy Pape will be coor- special dessert treat for others to dinating beverages for all ages. -

Austin, Texas: Heart and Stroke Healthy City” May 14Th, 2008

Texas Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention System 2008 State Plan Conference “Austin, Texas: Heart and Stroke Healthy City” May 14th, 2008 Sabrina McCarty Public Health Educator II Austin/Travis County Health and Human Services Department Heart & Stroke Prevention System in Austin, Tx. Network Connections Primary Prevention Secondary Prevention Austin Heart and Stroke Task Force Members 1. American Heart Association - Texas Affiliate 2. Austin Fire Department 3. Austin Independent School District 4. Austin Parks and Recreation Department 5. Austin/Travis County Community Care Services Department 6. Austin/Travis County EMS Department 7. Austin / Travis County EMS System Office of the Medical Director 8. Austin/Travis County Health and Human Services Department (ATCHHSD) - African American Quality of Life Initiative 9. ATCHHSD - Environmental and Consumer Health Services 10. ATCHHSD– Steps to a Healthier Austin Program 11. Brackenridge Hospital 12. Heart Hospital of Austin & Austin Heart 13. People’s Community Clinic 14. Red Cross of Central Texas 15. Seton Community Health Centers 16. Seton Family of Hospitals 17. St. David's Healthcare 18. Sustainable Food Center Primary Prevention Social Marketing Physical Activity Healthy Nutrition Tobacco Use Prevention/Cessation Austin Independent School District Social Marketing Steps to a Healthier Austin: Social Marketing - iThrive Campaign Radio, TV, newspaper ads, billboards, Transit ads, Movie ads, point of-decision prompts/Take the Stairs campaign posters, fliers, brochures, magnets, t-shirts, caps, sweat bands, canvas bags, Brigade Valenthrives; Holiday Bus Ads & Posters August Billboards Physical Activity Austin Parks and Recreation Department Outdoor/Indoor recreation areas 100+ Estimated mileage of trails 206 Community/neighborhood parks developed 17 Community recreation centers Walk Texas – Active Austin Area Walk Across Texas RunTex free walk/run classes PE Department Mayor’s Fitness Council Marathon Kids Program Printing funded by Steps to a Healthier Austin Program. -

Austin, Texas: Managing for Growth, Healthy Landscapes, and Wildfire Risk Reduction

January 2016 Austin, Texas: Managing For Growth, Healthy Landscapes, And Wildfire Risk Reduction Leaders in Wildfire Adaptation OVERVIEW Wildfires across the American West Introduction are increasing in frequency, size, and severity. The impacts from climate Austin, Texas, the state capital, is the the fastest growing big city in change and increasing growth within the country. Between 2013 and 2014, Austin added more than 25,000 the region’s Wildland-Urban Interface new residents, bringing the 2014 total population to 912,791 people.1 (WUI), further exacerbate the risks from Coupled with high growth, the city ranks third highest among 13 wildfires. western urban areas for homes at risk for wildfire damage,2 with more than 25 percent of its houses threatened by wildfires. Urban areas in the West are increasingly responding to the challenges of wildfire The City of Austin and surrounding Travis County are also home risk management through unique land to a geographically unique region of Texas known as the Balcones use planning tools which affect the pace, Escarpment, which separates the Edwards Plateau from the Blackland pattern, and scale of development. Prairie. As a result, the region contains diverse ecological landscapes, Austin, Texas is one of five communities which in turn brings particular considerations regarding how wildfire profiled by Headwaters Economics mitigation efforts are managed alongside other sustainability objectives, in a report identifying some of these such as habitat management and endangered species preservation. innovative land use planning strategies, including: • Close interdepartmental collaboration between the fire department and other city staff to conduct prescribed burns within the city limits, reducing fuel loading. -

Austin Fire Department Uses Qlikview to Improve Operations, Performance

QlikView | Customer Success Story | Austin Fire Department Austin Fire Department Solution Overview Austin Fire Department (AFD) uses QlikView to improve Municipal fire department serving the City of Austin, Texas operations, performance, Industry Government and service Function Executive, operations, finance, HR Geography United States AFD used to manage by anecdote, intuition, and assumption. With QlikView, our decisions are based on data-supported Challenges facts. We can test an assumption before we act on it and • Lack of visibility into operations and performance data measure a decision after it’s made. • Unable to effectively extract, integrate, “ and analyze enterprise data from seven Elizabeth Gray, distinct databases Business Systems Analyst Supervisor, Austin Fire Department • Improve reporting efficiency to improve operations, staff morale, and to ease staff stress Austin Fire Department (AFD) has a but” pulled it out with tweezers,” said Solution proud history of serving the more than Elizabeth Gray, AFD’s Business Systems AFD deployed QlikView to 16 users 750,000 residents of Austin, TX. The Analyst Supervisor. in 12 weeks. With QlikView, AFD now department, which responds to approxi- analyzes 911 calls, response times, mately 75,000 calls annually, holds as its QlikView: Better business apparatus deployment and usage, mission to protect lives and property. intelligence for better service personnel absences and leave, budgets The department began the search for and finances, firefighter staffing, cadet recruitment and hiring, and work orders. a Business Intelligence (BI) solution. It Using QlikView (64-bit), AFD immediately turned to QlikView after reading about leveraged the data stored in different the software in DM Review. “We ap- databases to achieve the department’s proached QlikView with a good deal of first-ever real time view of operational skepticism,” said Gray. -

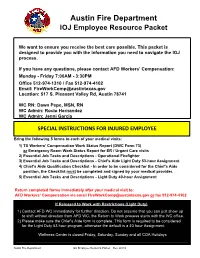

Austin Fire Department IOJ Employee Resource Packet

Austin Fire Department IOJ Employee Resource Packet We want to ensure you receive the best care possible. This packet is designed to provide you with the information you need to navigate the IOJ process. If you have any questions, please contact AFD Workers' Compensation: Monday - Friday 7:00AM - 3:30PM Office 512-974-1310 / Fax 512-974-4102 Email: [email protected] Location: 517 S. Pleasant Valley Rd, Austin 78741 WC RN: Dawn Pepe, MSN, RN WC Admin: Rocio Hernandez WC Admin: Jenni Garcia SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR INJURED EMPLOYEE Bring the following 5 forms to each of your medical visits: 1) TX Workers' Compensation Work Status Report (DWC Form 73) or Emergency Room Work Status Report for ER / Urgent Care visits 2) Essential Job Tasks and Descriptions - Operational Firefighter 3) Essential Job Tasks and Descriptions - Chief's Aide Light Duty 53-hour Assignment 4) Chief's Aide Qualification Checklist - In order to be considered for the Chief's Aide position, the Checklist must be completed and signed by your medical provider. 5) Essential Job Tasks and Descriptions - Light Duty 40-hour Assignment Return completed forms immediately after your medical visit to: AFD Workers' Compensation via email [email protected] or fax 512-974-4102 If Released to Work with Restrictions (Light Duty): 1) Contact AFD WC immediately for further direction. Do not assume that you can just show up to shift without direction from AFD WC, the Return to Work process starts with the WC office. 2) Please make sure the Chief's Aide form is complete. This form is required to be considered for the Light Duty 53 hour program, otherwise the default is a 40 hour Assignment. -

Course Objectives

INF 388E Historical Museums: Context and Practice, Fall 2014 Professor: Dr. Patricia K. Galloway Course Meeting Time: Wednesday, 12-3, UTA 1.502 Email:[email protected] Phone:(512) 232-9220 Office:UTA 5.436 Office Hours: by appointment Contact: Please use email in preference to telephone Teaching Assistant: Pearl Ko Email:[email protected] Contact: Please use email Course Description The purpose of this course is to look at and think about the process of museum exhibit creation in historical museums, from planning through development to opening and maintenance, as a negotiation among many stakeholders for influence upon the story that is told. We will consider the many facets of historical museums: their institutional positioning, including history and resources; the interests and concerns of museum employees (registrars, researchers, curators, conservators, education specialists, support staff, and volunteers); the influence of the public, both the "audience" public and those whose interests are directly affected and/or represented by an exhibit's story; and the role of contractual professionals when they are used (designers, exhibit construction firms, visitor studies experts). As a field for the study of this knowledge we will use the range of historical museums and museum-like venues in Austin where informal learning about history is available to citizens. Documented Disability Statement Students with disabilities may request appropriate academic accommodations from the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement, Services for Students with Disabilities, telephone 512-471- 6259. Religious Holy Days: By UT Austin policy, you must notify me of your pending absence at least fourteen days prior to the date of observance of a religious holy day. -

December 2014

December 2014 Letter from the Chair As another year comes to an end, I would like to wish holiday greetings to one and all in the neighborhood. We all have so much for which we should be thankful. We are fortunate to live in a very livable neighborhood and be surrounded by such wonderful neighbors. I feel so lucky when I see how our community will pull together for each other. I guess it all starts with knowing your neighbors. Our old city lots on narrow streets provides us opportunities to bring us together. Many of us have taken advantage of those opportunities and have come to know and love our neighbors. We have chosen to live in a community that has not only a diverse and distinctive architectural fabric but is filled good people who are good neighbors. Please take advantage of another opportunity to learn about your community and meet your neighbors by attending the OWANA general membership meeting on Tuesday, December 2nd. The agenda is filled with information regarding proposed projects affecting the neighborhood. Specific items to be discussed include improvements at West Austin Park, the proposed mixed-use development at the former AT&T service center on W. 5th Street, and updates on zoning and transportation projects. One critical item of the December agenda is the election of a new Steering Committee. We thank those who have served this year and offer support to those who have volunteered to serve next year. Our neighborhood is so distinctive and special because of the volunteers who have stepped up in the past and those who continue that line of service to us. -

Austin Fire Department IOJ Employee Resource Packet

Austin Fire Department IOJ Employee Resource Packet We want to ensure you receive the best care possible. This packet includes: AFD Policy E110.3, City of Austin Introduction, City of Austin Benefits Related to Workers' Comp, FMLA, Workers' Comp Insurance Information, Texas Department of Insurance DWC-41 form, Notice of Injured Employee Rights and Responsibilities in the Texas Workers' Compensation System, Office of Injured Employee Counsel First Responder Liaison, and Texas Department of Insurance Return to Work Checklist. If you have any questions, please contact AFD Workers' Compensation: Office Tel: 512-974-1310 / Fax: 512-974-4102 Email: [email protected] Location: 517 S. Pleasant Valley Rd, Austin 78741 WC $GPLQ: -HQQL*DUFLDH[W WC Admin: Rocio Hernandez H[W WC 51: 'DZQ3HSHH[W SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR INJURED EMPLOYEE 7KH:&,QIR )RUPVHPDLOZLOOFRQVLVWRIVSHFLDOLQVWUXFWLRQVDQGGLIIHUHQWDWWDFKPHQWV 3OHDVHPDNHVXUHWRUHDGWKHIXOOHPDLODQGFRQWDFWRXURIILFHZLWKDQ\TXHVWLRQVRU FRQFHUQV ,I<RXU'XW\6WDWXV&KDQJHV ¾ &RQWDFW$)':&LPPHGLDWHO\IRUIXUWKHUGLUHFWLRQ'RQRWDVVXPHWKDW\RXFDQMXVW VKRZXSWRVKLIWZLWKRXWGLUHFWLRQIURP$)':&WKH5HWXUQWR:RUNSURFHVVVWDUWVZLWK our office. ¾ If applicable, please make sure the Chief's Aide form is complete. This form is required to be considered for the Light Duty 53 hour program, otherwise the default is a 40 hour Assignment. ¾ Return completed forms immediately after your medical visit to AFD WC via email or fax. :HOOQHVV&HQWHULVFORVHG)ULGD\6DWXUGD\6XQGD\DQGDOO&2$+ROLGD\V Austin Fire Department IOJ Employee Resource Packet – Rev. 2020 CITY OF AUSTIN WORKERS’ COMPENSATION INTRODUCTION The City of Austin is committed to providing Workers’ Compensation benefits in accordance with the regulations set forth in the Texas Workers’ Compensation Act and Rules. The Texas Workers’ Compensation system has established rights and responsibilities for employees who are injured on-the- job or whose illness is work-related. -

Austin Fire Department Application

Office of the Austin Fire Department P.O. Box 129 Austin, AR 72007 Chris Nelson Bernadette Chamberlain Fire Chief Mayor, City of Austin Application for Employment Austin Fire Department Administration Office 10 Moats Lane Austin, AR 72007 Equal Opportunity Employer Please read this application carefully and complete each item. 1.) You will need to include you’re the items listed in Section VII with your application. (DD-214 is your military discharge papers—if applicable.) 2.) A copy of your drivers license may be made at the Austin City Hall. 3.) The Affidavit / Disclaimer in Section VII, must be read, signed and dated. 4.) The Authorization to Release Information must be signed in the presence of a Notary Public. You can find one at the Austin City Hall. Please return applications to the address listed above, or mail to P.O. Box 129 Austin, AR 72007. 1 Austin Fire Department Administrative Office P.O. Box 129 Austin, AR 72007 Application for Employment Position Applied for: (Fire Fighter, EMS, etc.) Today’s Date Section I: Personal Information Last Name First Name Middle Maiden Address: Street/Route/Box Number City State ZIP Telephone: Date of Birth: Social Security #: Driver’s License #: ST: List and other names used (i.e., nicknames, last names, etc.): Name of Spouse: Spouse Work Phone: Dependents Name of Dependent DOB Relationship 1 2 3 4 Section II: Military History List the following information concerning military duty, if applicable. Branch of Service Serial Number Enlistment Discharge Discharge Type Rank when discharged: Are you a member of a Reserve Unit? Give unit and length of time remaining: Section III: Residence History List residences for the past 10 years, beginning with your present address: Attach additional sheet, if necessary.