Seven Economic Challenges for Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technocrat Or Silovik Special Raport on Russian Governors

SPECIAL REPORT 26/02/2018 TECHNOCRAT OR SILOVIK SPECIAL RAPORT ON RUssIAN GOVERNORS The Warsaw Institute Foundation TECHNOCRAT OR SILOVIK. SPECIAL REPORT ON RUSSIAN GOVERNORS • The large-scale personnel changes in the Russian Federation indicates that such a situation is not only due to the pre-election campaign as loyal and efficient people are needed in order to ensure the proper result of the vote. It constitutes an element of a new role of the regions in the Putin regime, which may be associated with the start of his new presidential term. • The aforementioned personnel reshuffles result from the state’s increasing centralisation, which seems to be additionally fuelled by growing importance of the so-called siloviki. • The entire process has begun right after changes within the leadership of the Presidential Administration (also referred as PA). The key role is played by its head, Anton Vaino, as well as Sergey Kiriyenko who has recently replaced Vyacheslav Volodin as first deputy chief of staff of the Presidential Administration. • The fact of restoring direct gubernatorial election in 2012 has only seemingly strengthened their position. Indeed, it is getting weaker, if only because the president is given full freedom to dismiss governors and appoint acting ones, who confirm their mandate in a fully controlled election. • Importantly, none of the changes, which occurred in 2017, could be justified from economic point of view. Such regions as Mordovia, Khakassia and Kabardino-Balkar struggle with the most difficult financial situation. Even though, governors of these regions managed to retain their positions. Interestingly, it is no longer enough to maintain political calm (with no protests being organized), demonstrate economic successes and to obediently fulfill Putin’s decrees. -

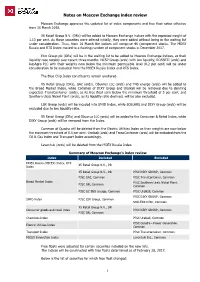

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

The North Caucasus: the Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law

The North Caucasus: The Challenges of Integration (III), Governance, Elections, Rule of Law Europe Report N°226 | 6 September 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Russia between Decentralisation and the “Vertical of Power” ....................................... 3 A. Federative Relations Today ....................................................................................... 4 B. Local Government ...................................................................................................... 6 C. Funding and budgets ................................................................................................. 6 III. Elections ........................................................................................................................... 9 A. State Duma Elections 2011 ........................................................................................ 9 B. Presidential Elections 2012 ...................................................................................... -

Russia and Saudi Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges by John W

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 35 Russia and Saudi Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges by John W. Parker and Thomas F. Lynch III Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Vladimir Putin presented an artifact made of mammoth tusk to Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman Al Saud in Riyadh, October 14–15, 2019 (President of Russia Web site) Russia and Saudi Arabia Russia and Saudia Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges By John W. Parker and Thomas F. Lynch III Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 35 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2021 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Why Governments Target Civil Society and What Can Be Done in Response a New Agenda

APRIL 2015 Why Governments Target Civil Society and What Can Be Done in Response A New Agenda AUTHOR Sarah E. Mendelson A Report of the CSIS Human Rights Initiative 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202-887-0200 | www.csis.org Cover photo: Shutterstock.com. Blank Why Governments Target Civil Society and What Can Be Done in Response A New Agenda Author Sarah E. Mendelson A Report of the CSIS Human Rights Initiative April 2015 About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has become one of the world’s preeminent international institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global health and economic integration. Former U.S. senator Sam Nunn has chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees since 1999. Former deputy secretary of defense John J. Hamre became the Center’s president and chief executive officer in 2000. -

Russia Intelligence

N°70 - January 31 2008 Published every two weeks / International Edition CONTENTS SPOTLIGHT P. 1-3 Politics & Government c Medvedev’s Last Battle Before Kremlin Debut SPOTLIGHT c Medvedev’s Last Battle The arrest of Semyon Mogilevich in Moscow on Jan. 23 is a considerable development on Russia’s cur- Before Kremlin Debut rent political landscape. His profile is altogether singular: linked to a crime gang known as “solntsevo” and PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS sought in the United States for money-laundering and fraud, Mogilevich lived an apparently peaceful exis- c Final Stretch for tence in Moscow in the renowned Rublyovka road residential neighborhood in which government figures « Operation Succession » and businessmen rub shoulders. In truth, however, he was involved in at least two types of business. One c Kirillov, Shestakov, was the sale of perfume and cosmetic goods through the firm Arbat Prestige, whose manager and leading Potekhin: the New St. “official” shareholder is Vladimir Nekrasov who was arrested at the same time as Mogilevich as the two left Petersburg Crew in Moscow a restaurant at which they had lunched. The charge that led to their incarceration was evading taxes worth DIPLOMACY around 1.5 million euros and involving companies linked to Arbat Prestige. c Balkans : Putin’s Gets His Revenge The other business to which Mogilevich’s name has been linked since at least 2003 concerns trading in P. 4-7 Business & Networks gas. As Russia Intelligence regularly reported in previous issues, Mogilevich was reportedly the driving force behind the creation of two commercial entities that played a leading role in gas relations between Russia, BEHIND THE SCENE Turkmenistan and Ukraine: EuralTransGaz first and then RosUkrEnergo later. -

RUSSIA INTELLIGENCE Politics & Government

N°66 - November 22 2007 Published every two weeks / International Edition CONTENTS KREMLIN P. 1-4 Politics & Government c KREMLIN The highly-orchestrated launching into orbit cThe highly-orchestrated launching into orbit of of the «national leader» the «national leader» Only a few days away from the legislative elections, the political climate in Russia grew particu- STORCHAK AFFAIR larly heavy with the announcement of the arrest of the assistant to the Finance minister Alexey Ku- c Kudrin in the line of fire of drin (read page 2). Sergey Storchak is accused of attempting to divert several dozen million dol- the Patrushev-Sechin clan lars in connection with the settlement of the Algerian debt to Russia. The clan wars in the close DUMA guard of Vladimir Putin which confront the Igor Sechin/Nikolay Patrushev duo against a compet- cUnited Russia, electoral ing «Petersburg» group based around Viktor Cherkesov, overflows the limits of the «power struc- home for Russia’s big ture» where it was contained up until now to affect the entire Russian political power complex. business WAR OF THE SERVICES The electoral campaign itself is unfolding without too much tension, involving men, parties, fac- cThe KGB old guard appeals for calm tions that support President Putin. They are no longer legislative elections but a sort of plebicite campaign, to which the Russian president lends himself without excessive good humour. The objec- PROFILE cValentina Matvienko, the tive is not even to know if the presidential party United Russia will be victorious, but if the final score “czarina” of Saint Petersburg passes the 60% threshhold. -

Interview with Yulia Malysheva

A Revolution of the Mind INTERVIEW WITH YULIA MALYSHEVA ulia Sergeevna Malysheva is one of the leading youth activists in Russia. An elected Y municipal deputy in Moscow, a researcher at the Institute for the Economy in Transi- tion, and leader of the youth organization Oborona (which she cofounded) and of the youth branch of the SPS party, Malysheva also later became the leader of the youth branch of the People’s Democratic Union, the political movement led by former Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov. In this interview, she speaks about the possibility of a color revolution in Russia, cooperation with other domestic and international youth groups, the Kremlin’s worried reaction, the nature of the Nashi pro-Kremlin youth group, the attempts to unite the Russian democrats, the successes of Oborona, the chances the democrats have of returning to power, and what she expects from the West. Demokratizatsiya: Tell us about Oborona. Malysheva: Oborona is a youth organization that appeared with the Orange wave in Ukraine. It was important for us that many others were waiting for us, since youth have always been in the avant-garde. At that time, our adult colleagues kept arguing as to who was more important. In the end, they got 3 percent [in the Duma elections]. It was evi- dent that they were not well presented before the Russian voters. We founded Oborona not only with young people who sympathize with SPS, Yabloko, the [former SPS leader and independent candidate Irina] Khakamada movement and other such formations—but also with those who support the democratic process and oppose the Putin regime. -

Russia Macro-Politics: Political Pragmatism Or, Economic Necessity

The National Projects December 2019 Population and GDP (2020E data) The long and winding road Population 146.8 GDP, Nominal, US$ bln $1,781 Plans are worthless. Planning is essential” GDP/Capita, US$ $12,132 Dwight D. Eisenhower GDP/Capita, PPP, US$ $27,147 Source: World Bank, World-o-Meters, MA The National Projects (NP) are at the core of the Russian government’s efforts to pull the economy out of the current slump, National Projects - Spending* to create sustainable diversified long-term growth and to improve Rub, Bln US$ Bln lifestyle conditions in Russia. It is the key element of President Putin’s Human Capital 5,729 $88 effort to establish his legacy. Health 1,726 $27 Education 785 $12 We are now initiating coverage of the National Projects strategy. We Demographics 3,105 $48 will provide regular detailed updates about the progress in each of Culture 114 $2 the major project sectors, focusing especially on the opportunities Quality of Life 9,887 $152 Safer Roads 4,780 $74 for foreign investors and on the mechanisms for them to take part. Housing 1,066 $16 ▪ What is it? A US$390 billion program of public spending, designed Ecology 4,041 $62 to stimulate investment, build infrastructure and improve health Economic Growth 10,109 $156 and well-being by 2024, i.e. the end of the current presidential Science 636 $10 Small Business Development 482 $7 term. Digital Economy 1,635 $25 ▪ Is this a return to Soviet-style planning? For some of the NPs, Labour productivity 52 $1 Export Support 957 $15 especially those involving infrastructure, it certainly looks like it. -

RUSSIA and CHINA and Central Asia Programme at ISPI

RUSSIA AND CHINA. ANATOMY OF A A PARTNERSHIP OF AND RUSSIA CHINA. ANATOMY Aldo Ferrari While the “decline of the West” is now almost taken is Head of the Russia, Caucasus for granted, China’s impressive economic performance RUSSIA AND CHINA and Central Asia Programme at ISPI. and the political influence of an assertive Russia in the international arena are combining to make Eurasia a key Founded in 1934, ISPI is Eleonora Tafuro Ambrosetti Anatomy of a Partnership hub of political and economic power. That, certainly, an independent think tank is a Research Fellow committed to the study of is the story which Beijing and Moscow have been telling at the Russia, Caucasus and international political and Central Asia Centre at ISPI. for years. edited by Aldo Ferrari and Eleonora Tafuro Ambrosetti economic dynamics. Are the times ripe for a “Eurasian world order”? What It is the only Italian Institute exactly does the supposed Sino-Russian challenge to introduction by Paolo Magri – and one of the very few in the liberal world entail? Are the two countries’ worsening Europe – to combine research clashes with the West drawing them closer together? activities with a significant This ISPI Report tackles every aspect of the apparently commitment to training, events, solidifying alliance between Moscow and Beijing, but also and global risk analysis for points out its growing asymmetries. It also recommends companies and institutions. some policies that could help the EU to deal with this ISPI favours an interdisciplinary “Eurasian shift”, a long-term and multi-faceted power and policy-oriented approach made possible by a research readjustment that may lead to the end of the world team of over 50 analysts and as we have known it. -

CONGRESSIONAL PROGRAM U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era

CONGRESSIONAL PROGRAM U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era May 29 – June 3, 2018 Helsinki, Finland and Tallinn, Estonia Copyright @ 2018 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute 2300 N Street Northwest Washington, DC 20037 Published in the United States of America in 2018 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America U.S.-Russia Relations: Policy Challenges in a New Era May 29 – June 3, 2018 The Aspen Institute Congressional Program Table of Contents Rapporteur’s Summary Matthew Rojansky ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Russia 2018: Postponing the Start of the Post-Putin Era .............................................................................. 9 John Beyrle U.S.-Russian Relations: The Price of Cold War ........................................................................................ 15 Robert Legvold Managing the U.S.-Russian Confrontation Requires Realism .................................................................... 21 Dmitri Trenin Apple of Discord or a Key to Big Deal: Ukraine in U.S.-Russia Relations ................................................ 25 Vasyl Filipchuk What Does Russia Want? ............................................................................................................................ 39 Kadri Liik Russia and the West: Narratives and Prospects ......................................................................................... -

Stability in Russia's Chechnya and Other Regions of the North Caucasus: Recent Developments

Order Code RL34613 Stability in Russia’s Chechnya and Other Regions of the North Caucasus: Recent Developments August 12, 2008 Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Stability in Russia’s Chechnya and Other Regions of the North Caucasus: Recent Developments Summary In recent years, there have not been major terrorist attacks in Russia’s North Caucasus — a border area between the Black and Caspian Seas that includes the formerly breakaway Chechnya and other ethnic-based regions — on the scale of the June 2004 raid on security offices in the town of Nazran (in Ingushetia), where nearly 100 security personnel and civilians were killed, or the September 2004 attack at the Beslan grade school (in North Ossetia), where 300 or more civilians were killed. This record, in part, might be attributed to government tactics. For instance, the Russian Interior (police) Ministry reported that its troops had conducted over 850 sweep operations (“zachistki”) in 2007 in the North Caucasus, in which they surround a village and search every house, ostensibly in a bid to apprehend terrorists. Critics of the operations allege that the troops frequently engage in pillaging and gratuitous violence and are responsible for kidnapings for ransom and “disappearances” of civilians. Although it appears that major terrorist attacks have abated, there reportedly have been increasingly frequent small-scale attacks against government targets. Additionally, many ethnic Russian and other non-native civilians have been murdered or have disappeared, which has spurred the migration of most of the non- native population from the North Caucasus.