Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The African Scare of Fall Armyworm: Are South African Farmers Immune?

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITY STUDIES Vol 12, No 1, 2020 ISSN: 1309-8063 (Online) THE AFRICAN SCARE OF FALL ARMYWORM: ARE SOUTH AFRICAN FARMERS IMMUNE? Witness Maluleke University of Limpopo Email: [email protected] Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6228-1640 –Abstract– The manifestations of Fall Armyworm [FAW] (Spodoptera frugiperda) in South Africa were all clearly reminders of the seriousness of this epidemic in 2019. The scare caused by FAW as an African Moth continues to multiple largely. This is becoming a factor for African farmers, seeking urgent acknowledgement of the associated detrimental effects mapped with economic, social, environmental opportunities and fully exploitation of sustainable agriculture in the country and elsewhere. This study adopted qualitative research approach, with an aid of non- empirical research design: Systematic review, closely looking at recent reputable reports across globe, while using South Africa as a case study, from 1995-2019 (i.e. 24 years’ projection). This study found that South African readiness against FAW is [currently] highly questionable, with the consequences of failing to act clearly felt by many South African farmers, therefore, the strategies geared towards this pandemic [might] not be able to totally stop the clock on its effects on farming practices, however, revisiting and adding to the available strategies can be beneficial to this sector to holistically affirm and sustain agriculture in South Africa as one of the two sectors at the core of economic development. It is concluded that there is no single solution to respond to this elusive spread, thus, multi-agency approach is highly sought. -

Fall Armyworm

How to identify... Fall armyworm Fall armyworm or ‘American armyworm’ is a new pest in Africa that is currently attacking maize. This pest originates from the Americas, but it has recently been found in several countries in West and Southern Africa. This guide will help you to recognize fall armyworm and tell it apart from similar caterpillars such as other armyworms, stalk borers and cut worms. IDENTIFICATION Half-grown or fully grown caterpillars are the easiest to identify. Fall armyworm caterpillars have a characteristic pattern of dark pimples (spots) on their backs, each spot has a short bristle (hair). Although the skin looks rough it is smooth to the touch. Look out for four dark spots forming a square on the second to last segment (red circle). Each of the other body segments also has four spots, but they do not from a square pattern (yellow circle). The head is dark and shows a characteristic upside down Y-shaped pale marking on the front (blue circle). ©Russ Ottens, Bugwood.org ✔ ©Russ Ottens, Bugwood.org ✔ ©Russ Ottens, Bugwood.org ✔ Other armyworms, maize stem borer and cotton bollworm ©Donald Hobern, Denmark Hobern, ©Donald ✘ Denmark Hobern, ©Donald ✘ The cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) often shows a similar pattern of dots on its back, but its head is usually paler, and although they can also show an inverted Y this is usually a similar colour to the rest of the head. Unlike the fall armyworm they feel rough to the touch due to tiny spines. us Kloppers/PANNAR us ©Rik ✘ Bugwood.org Cranshaw, ©Whitney ✘ Flickr Reyes, Marquina ©David ✘ African armyworm Beet armyworm African cotton leafworm Spodoptera exempta Spodoptera exigua Spodoptera littoralis ©NBAIR ✘ CABI ©R.Reeder, ✘ Spotted stem borer African maize stalk borer Chilo partellus Busseola fusca Damage caused by Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) ©J. -

Occurrence and Distribution of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera Frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and Other Moths on Maize in Ghana B

OCCURRENCE AND DISTRIBUTION OF FALL ARMYWORM, SPODOPTERA FRUGIPERDA (LEPIDOPTERA: NOCTUIDAE) AND OTHER MOTHS ON MAIZE IN GHANA By DJIMA KOFFI ID: 10600839 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (M.PHIL.) DEGREE IN ENTOMOLOGY. AFRICAN REGIONAL POSTGRADUATE PROGRAMME IN INSECT SCIENCE (ARPPIS) UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON, ACCRA, GHANA AUGUST, 2018 * JOINT INTER-FACULTY INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR THE TRAINING OF ENTOMOLOGISTS IN WEST AFRICA COLLABORATING DEPARTMENTS: ANIMAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION SCIENCE (SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES) AND CROP SCIENCE (SCHOOL OF AGRICULTURE) COLLEGE OF BASIC AND APPLIED SCIENCES DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of the original work personally done by me for the award of a Master of Philosophy Degree in Entomology at the African Regional Postgraduate Programme in Insect Science (ARPPIS), University of Ghana, Legon. All the references to other people’s work have been duly acknowledged and this thesis has not been submitted in part or whole for the award of a degree elsewhere. Signature……………....................................... Date………………………………………….. DJIMA KOFFI (STUDENT) Signature……………....................................... Date………………………………………….. DR. ROSINA KYEREMATEN (PRINCIPAL SUPERVISOR) Signature……………....................................... Date………………………………………….. DR. VINCENT Y. EZIAH (CO-SUPERVISOR) Signature……………....................................... Date………………………………………….. DR. -

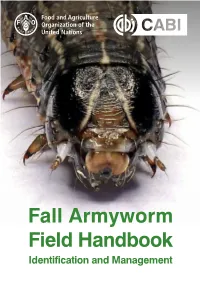

Fall Armyworm Field Handbook Identification and Management FAO and CABI (2019) Fall Armyworm Field Handbook: Identification and Management, First Edition

Fall Armyworm Field Handbook Identification and Management FAO and CABI (2019) Fall Armyworm Field Handbook: Identification and Management, First Edition. Cover Photo: Fall armyworm larva ©Georg Goergen, IITA This field handbook is an adapted version of FAO and CABI (2019) Community-Based Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) Monitoring, Early warning and Management, Training of Trainers Manual, First Edition. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. It is intended to help extension workers and farmers in the field to identify fall armyworm and know how to manage it. The Training of Trainers Manual was funded by US Foreign Disaster Assistance, Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance, US Agency for International Development (USAID). The editing and printing of this handbook was made possible with the kind financial support of the Netherlands Directorate General for International Cooperation (DGIS). The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of FAO, CABI, USAID, UKAID or DGIS. © FAO and CABI, 2019 Further information Fall armyworm portal: www.cabi.org/fallarmyworm Fall armyworm FAO: www.fao.org/fall-armyworm/en Contents How to identify fall armyworm ........................................... 4 How to monitor fall armyworm in the field ....................... 19 How to manage fall armyworm ....................................... 25 Find out more................................................................... 36 4 FALL ARMYWORM FIELD HANDBOOK IDENTIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT How to identify fall armyworm Fall armyworm larvae (or caterpillars) are similar to caterpillars of other related pests (Figure 1). Look for the following features to determine if the caterpillar you have found in your maize is fall armyworm or belongs to another species. • A dark head with a pale, upside-down Y-shaped marking (Figure 2, black circle). -

Fall Armyworm: Impacts and Implications for Africa Evidence Note Update, October 2018

Fall armyworm: impacts and implications for Africa Evidence Note Update, October 2018 Rwomushana, I., Bateman, M., Beale, T., Beseh, P., Cameron, K., Chiluba, M., Clottey, V., Davis, T., Day, R., Early, R., Godwin, J., Gonzalez-Moreno, P., Kansiime, M., Kenis, M., Makale, F., Mugambi, I., Murphy, S., Nunda. W., Phiri, N., Pratt, C., Tambo, J. KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE Executive Summary This Evidence Note provides new evidence on the distribution and impact of FAW in Africa, summarises research and development on control methods, and makes recommendations for sustainable management of the pest. FAW biology FAW populations in Africa include both the ‘corn strain’ and the ‘rice strain’. In Africa almost all major damage has been recorded on maize. FAW has been reported from numerous other crops in Africa but usually there is little or no damage. At the moment managing the pest in maize remains the overriding priority. In Africa FAW breeds continuously where host plants are available throughout the year, but is capable of migrating long distances so also causes damage in seasonally suitable environments. There is little evidence on the relative frequency of these two scenarios. Studies show that natural enemies (predators and parasitoids) in Africa have “discovered” FAW, and in some places high levels of parasitism have already been found. Distribution and Spread FAW in Africa Rapid spread has continued and now 44 countries in Africa are affected. There are no reports from North Africa, but FAW has reached the Indian Ocean islands including Madagascar. Environmental suitability modelling suggests almost all areas suitable for FAW in sub-Saharan Africa are now infested. -

Manual on Integrated Fall Armyworm Management

Manual on Integrated fall armyworm management Manual on Integrated fall armyworm management Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Nay Pyi Taw, 2020 Required citation: FAO and PPD, 2020. Manual on Integrated fall armyworm management. Yangon, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9688en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-132903-0 [FAO] © FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. -

NPV: a New Biological Control for Armyworm in Africa

NATURAL RESOURCES INSTITUTE For further information please contact: • David Grzywacz Natural Resources Institute NPV: a New Biological Natural Resources Institute University of Greenwich at Medway Central Avenue United Republic of Tanzania E-mail: [email protected] Ministry of Agriculture and Chatham Maritime Control for Armyworm Food Security • Wilfred Mushobozi Kent ME4 4TB Eco AgriConsultancy Services Ltd, Tanzania in Africa E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 01634 880088 Telephone from outside the UK: +44 1634 880088 • Ken Wilson Fax: 01634 883386 Lancaster University Fax from outside the UK: +44 1634 883386 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.nri.org This document is available in other formats on request University of Greenwich, a charity and company limited by guarantee, registered in England (reg. no. 986729). Registered office: Old Royal Naval College, Park Row, Greenwich, London SE10 9LS. D1033-8 NPV: a New Biological Control for Armyworm The African armyworm is the caterpillar What is NPV? Is NPV safe to us? pheromone traps that attract male of the moth Spodoptera exempta and is armyworm moths using the artificial scent a major crop pest in Eastern Africa. Its NPV is a naturally present disease that Yes. NPV only infects the armyworm and of mating female armyworms. The annual outbreaks frequently escalate kills armyworm and helps control its cannot harm man, domestic animals, catches of armyworm in these traps are into major plagues that can spread outbreaks. The NPV disease is caused by plants or even other insects. An used to forecast armyworm outbreaks at across much of the region, causing an insect virus that occurs naturally in international report by the Organisation for a local level and alert farmers much faster major damage to cereal crops and Africa. -

Pathogen Persistence in Migratory Insects: High Levels of Vertically-Transmitted Virus Infection in field Populations of the African Armyworm

Evol Ecol (2010) 24:147–160 DOI 10.1007/s10682-009-9296-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Pathogen persistence in migratory insects: high levels of vertically-transmitted virus infection in field populations of the African armyworm Luisa Vilaplana Æ Kenneth Wilson Æ Elizabeth M. Redman Æ Jenny S. Cory Received: 30 April 2008 / Accepted: 6 February 2009 / Published online: 28 February 2009 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 Abstract Pathogens face numerous challenges to persist in hosts with low or unpre- dictable population densities. Strategies include horizontal transmission, such as by the production of propagules that persist in the environment, and vertical transmission from adults to offspring. While many pathogens are capable of horizontal and vertical trans- mission little is known of their relative roles under realistic conditions of changing population densities. Insect baculoviruses can be transmitted both horizontally and verti- cally, although much of the work on baculovirus transmission has focussed on horizontal transmission that can be effective at high host densities. Here, we examine the prevalence of a vertically-transmitted, covert infection of nucleopolyhedrovirus (NPV) in field pop- ulations of the African armyworm, Spodoptera exempta, in Tanzania. African armyworm is a major pest of graminaceous crops in Africa and despite its migratory nature and boom and bust dynamics, NPV epizootics are common and can be intense at the end of the multi- generation armyworm season. We found that virtually all the insects collected in the field L. Vilaplana Á E. M. Redman Á J. S. Cory Molecular Ecology and Biocontrol Group, NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Mansfield Road, Oxford OX1 3SR, UK K. -

The New Invasive Fall Armyworm (Faw) in South Africa

Insect Ecology—Insect Pests : FACT SHEET NO. 4 THE NEW INVASIVE FALL ARMYWORM (FAW) IN SOUTH AFRICA The FAW originates from the tropical regions of the United States, Argentina, and the Caribbean region and is a serious pest of maize in Brazil and other countries. The first reports of outbreaks of the Fall Armyworm (FAW) in Africa came from several West and Central African countries early in 2016, but were initially attributed to indigenous Spodoptera spp. During December 2016, the first unconfirmed reports of armyworm damage to maize were received from Zambia and Zim- babwe. In January 2017, the South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF) received reports of an unknown armyworm damaging maize plants on farms in the Limpopo and North West provinces. A taxonomist at the ARC- PPRI, Biosystematics Division positively identified the male moth specimens collected, as the Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). The FAW flies on prevailing winds, has a short life-cycle, and attacks a wide range of crops, rendering it a serious economic risk to our farmers. It is classified as an A1 quarantine pest on the list of European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation (EPPO). IDENTIFICATION Eggs are laid in batches of 20-250 on the underside of leaves. Larvae (worms): six developmental instars from egg to moth stage. Young larvae are difficult to identify morphologically as the early instars resemble those of several other Noctuids. Instar Body length Colouring Markings # (mm) Green with black 1, 2 1,5 to 3,5 None head Dorsal area tan Four dark pinacula or colour, ventral raised spots arranged in 3, 4 6 to 10 area green. -

Black Armyworm on Maize Spodoptera Exempta Black Armyworm; African Armyworm; Nutgrass Armyworm Prevention Monitoring Direct Control

PEST MANAGEMENT DECISION GUIDE: GREEN LIST Black armyworm on maize Spodoptera exempta Black armyworm; African armyworm; Nutgrass armyworm Prevention Monitoring Direct Control l Grow less susceptible varieties if available l Monitor immediately after germination and check weekly for l For small farms, hand pick caterpillars l Plant early to try and avoid severe damage by symptoms. and eggs and destroy them by crushing second generation armyworms l Check for armyworms late evening/early morning. They often feed or feed to chickens or ducks l Avoid planting close to overgrazed grasslands at night and hide under debris during the day l Dig a 30 cm deep trench with vertical which provide food and refuge for caterpillars l Look for caterpillars in field margins, low areas where plants have sides around the field to trap marching Black armyworm; dorsal caterpillars. Collect and destroy them surface of larva, showing l Remove weeds such as Amaranthus and grassy lodged, beneath plant debris around the base of plants, underneath markings (©Rikus Kloppers/ weeds since they are food for young caterpillars, plant leaves and on young, soft shoots and stems l Apply neem. Seed extract: 50g/L water PANNAR Seed (Pty) Ltd, with a little soap. Greytown, South Africa) and keep other weeds to provide shelter and l Monitor closely when rains come after a long period of drought, food for natural enemies causing grass growth. l Apply Pyrethrum: Grind Pyrethrum l Encourage the presence of natural enemies l Look for chewed leaves making the crop look ragged. Only the flowers into a dust, use pure or mix with such as birds, toads, lizards, small mammals, midribs are left in severe cases a carrier like talc or lime, then sprinkle over plants insects and spiders, by planting trees and l You may find dark specks of frass from caterpillars on plant stems shrubs and leaves l Or use Pyrethrum powder: 20 g l If armyworm is suspect in the field, plough and powder/10 L water. -

Genetic Control of the Pre-Reproductive Period in Autographa Gamma (L.) (Silver V Moth) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)

Heredity 69 (1992) 458-464 Received 27 January 1992 Genetical Society of Great Britain Genetic control of the pre-reproductive period in Autographa gamma (L.) (Silver V moth) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) J. K. HILL & A. G. GATEHOUSE School of Biological Sciences, University of Wales, Bangor, Gwynedd LL 57 2UW, U.K. Adultsof the noctuid moth Autographa gamma undertake seasonal migrations into areas where they are unable to breed continuously. Individuals migrate into Britain each spring and offspring of these migrants probably return in autumn to over-wintering areas in North Africa and the Middle East, although the existence of these return migrations has been questioned. Insects usually migrate during the adults' pre-reproductive period (PRP). The length of this period is therefore an index of migratory potential because individuals with longer PRPs have more time to express their potential for flight and to travel further. Significant, positive full-sib correlations showed that female offspring with long PRPs came from families where their brothers had correspondingly long PRPs. This suggests that the same genes control the rate of reproductive development in both sexes. There was a rapid response to selection for short and long PRP, with separation of the lines by the second generation of selection. Sib-analysis and parent—offspring regressions showed that the genes with the greatest influence on PRP are X-linked, although there is also an autosomal influence. The significance of X-linkage of genes controlling the PRP is discussed in relation to the migratory strategy of A. gamma. Keywords:adultdiapause, Autographa gamma, migration, X-linkage. Introduction because it determines the interval over which individ- uals can express their capacity for flight. -

Generational Viral Transmission and Immune Priming Are Dose-Dependent

Received: 2 February 2021 | Accepted: 8 March 2021 DOI: 10.1111/1365-2656.13476 RESEARCH ARTICLE Trans- generational viral transmission and immune priming are dose- dependent Kenneth Wilson1 | David Grzywacz2 | Jenny S. Cory3 | Philip Donkersley1 | Robert I. Graham1 1Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK Abstract 2Department of Agriculture Health and 1. It is becoming increasingly apparent that trans- generational immune priming (i.e. Environment, Natural Resources Institute, the transfer of the parental immunological experience to its progeny resulting in University of Greenwich, Kent, UK 3Department of Biological Sciences, Simon offspring protection from pathogens that persist across generations) is a common Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada phenomenon not only in vertebrates, but also invertebrates. Likewise, it is known Correspondence that covert pathogenic infections may become ‘triggered’ into an overt infection Kenneth Wilson by various stimuli, including exposure to heterologous infections. Yet, rarely have Email: [email protected] both phenomena been explored in parallel. Present address 2. Using as a model system the African armyworm Spodoptera exempta, an eruptive Robert I. Graham, Department of Rural Land Use, SRUC, Craibstone Campus, Aberdeen, agricultural pest and its endemic dsDNA virus (Spodoptera exempta nucleopolyhe- UK drovirus, SpexNPV), the aim of this study was to explore the impact of parental Funding information inoculating- dose on trans- generational pathogen transmission and immune prim- Biotechnology and Biological Sciences ing (in its broadest sense). Research Council, Grant/Award Number: BB/F004311/1 and BB/P023444/1 3. Larvae were orally challenged with one of five doses of SpexNPV and survivors from these treatments were mated and their offspring monitored for viral mortal- Handling Editor: Rachael Antwis ity.