Wealth and Inequality in Ottoman Bursa-Canbakal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CREATING OPPORTUNITIES, GROWING VALUE Creating Opportunities, Growing Value

CREATING OPPORTUNITIES, GROWING VALUE Creating Opportunities, Growing Value The cover for our Integrated Annual Report reflects the focus that we place on our key roles and purpose in the Malaysian capital market. The deliberately minimalistic approach allows our mission statement to stand out from any distractions, while the figurative bull and bear reflect the symbols long associated with the stock market. Overall, the cover reflects our continuing value creation efforts regardless of the market conditions. TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION ABOUT POSITIONED FOR THIS REPORT VALUE CREATION 2 Continuing Our Integrated Reporting Journey 5 Who We Are 2 Scope and Boundaries 7 Our Performance 2 Material Matters 8 Our Value Creation Model 2 Reporting Principles and Framework 12 Overall Market Performance 2 Navigation Icons 14 Market Highlights 3 Forward-Looking Statement and Disclaimer 16 Corporate Events and News 3 Board of Directors’ Approval 20 Peer Comparison 22 Upcoming Financial Calendar Events SECTION SECTION OUR GOVERNANCE ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 81 Who Governs Us 129 List of Properties Owned by Bursa Malaysia Group 92 Who Leads Us 130 Statistics of Shareholdings 94 Key Senior Management 143 Additional Compliance Information Disclosures 95 Corporate Structure 96 Other Corporate Information 97 Corporate Governance Overview 107 Marketplace Report: Fair and Orderly Markets 114 Statement on Internal Control and Risk Management 123 Audit Committee Report VISION MISSION To be ASEAN’s leading, Creating Opportunities, sustainable and Growing Value globally-connected -

Bursa, Turkey

International Journal of Development and Sustainability ISSN: 2186-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 6 Number 12 (2017): Pages 1931-1945 ISDS Article ID: IJDS17092105 Urban sustainability and traditional neighborhoods, a case study: Bursa, Turkey Arzu Ispalar Çahantimur *, Rengin Beceren Öztürk, Gözde Kırlı Özer Uludag University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Bursa, Turkey Abstract The objective of the present study was to focus on the urban sustainability potential and traditional residential areas of historical cities based on the compact city concept. The study includes four sections. In the introduction, the important role that the cities play in sustainability was discussed with an emphasis on the significance of traditional housing areas in urban sustainability. In the second section, whether the compact city form is suitable for historic urban quarters was investigated with an empirical study conducted in Bursa, Turkey. In the study, home and home environment were considered as a transactional whole, which defines and defined by a set of cultural, social, and psychological factors, hence, a transactional theoretical approach was adopted. The study utilized observation and ethnological research methods in conjunction with surveys conducted with the residents of historic quarters in Bursa, which is one of the most historical cities in Turkey, a developing nation. The case study findings and policy recommendations on sustainable urban development in historic cities were addressed in the final section of the present study. Keywords: Urban Sustainability; Compact City; Traditional Neighborhood; Turkey; Bursa Published by ISDS LLC, Japan | Copyright © 2017 by the Author(s) | This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Balıkesir Logistic Atlas

www.gmka.gov.tr Balıkesir is the New Favorite for Investments with Developing Transportation Network On the junction of East-West and North-South connection roads, Balıkesir is a candidate for being the logistics center of Turkey. Recent highways and ongoing highway investments, projected railroad and port projects are making Balıkesir the door of Turkey to the world. These projects will make Balıkesir a bridge between metropoles and other provinces, as well as contributing to inter-province commercial activities. Marmara YALOVA Erdek Bandırma BİLECİK Gönen Manyas BURSA ÇANAKKALE Susurluk Balya Karesi Kepsut Edremit Havran Altıeylül İvrindi Dursunbey Bigadiç Savaştepe Gömeç Burhaniye KÜTAHYA Ayvalık Sındırgı MANİSA İZMİR UŞAK 2 Balıkesir on the Road to Become a Logistics Base Geographic location of Balıkesir and its close proximity to centers such as İstanbul, Bursa, İzmir increases the growth potential of the province. Being an alternative region in industry sector moves Balıkesir rapidly into becoming a logistics base. İSTANBUL TEKİRDAĞ 132 km ÇANAKKALE 190 km 90 km 115 km Bandırma 240 km 165 km 110 km 200 km BURSA 100 km 150 km BALIKESİR 140 km MANİSA 40 km İZMİR 3 Connection Roads to Neighboring Provinces Social, economic and logistics relations between provinces have been improved by increasing the length of the total divided roads connecting Balıkesir to neighboring provinces. Divided road construction works on the 220 km-highway connecting Balıkesir to Çanakkale has been completed and the road has been commissioned. Transportation infrastructure of 225 km Kütahya – Balıkesir divided road has been improved. Furthermore, transportation to Bursa, İzmir and Manisa provinces that are neighboring Balıkesir is provided with divided roads. -

International Seminar for UNESCO Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue: “The Influence of the Silk Roads on Turkish Culture and Art”

International Seminar for UNESCO Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue: “The influence of the Silk Roads on Turkish Culture and Art”. 30, October, 1990. Izmir, Turkey. Role and Importance of Izmir on the Silk Trade XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries Necmi ÜLKER Prof. Dr. Necmi ULKER Ege University, Izmir-TURKEY As has been known for many centuries, the silk trade either originates from Central Asia or Middle East goes back a long way. From China in a western direction, state dignitaries working for existing states and economically well-off people seemed to be in great need of silk and silk manufacturers over the centuries in the ancient and Middle Ages. One· can easily assume that silk manufacturers were used in large quantities especially in the palaces of the Sasanids, Arab states, Byzantines, Selcuqids, Ottomans as well as European states. This paper aims to show that in the trade of silk, Izmir as an international commercial center and a busy port has played an important role. The revival of Izmir as a significant trading center goes back to as early as 1620s. Supporting this fact, French historian Paul Masson states the arrival of Iranian silk in Izmir in 16211. As a matter of fact in the XVIIth century Iran was the main source of silk production and exporting country in the Middle East. Towards the end of the Ottoman-Iran war of 1615-18, Izmir had already become an important rival of Aleppo which was the center of English merchants in that century for silk originating from Iran.2 It can be said that, due to this war, the silk routes from Iran silk producing areas to Aleppo were continuously disrupted by the armed forces of the belligerent states. -

Turkey: Minorities, Othering and Discrimination, Citizenship Claims

Turkey: Minorities, Othering and Discrimination, Citizenship Claims Document Identifier D4.9 Report on 'Turkey: How to manage a sizable citezenry outside the country across the EU'. Version 1.0 Date Due 31.08.2016 Submission date 27.09.2016 WorkPackage WP4 Rivalling citizenship claims elsewhere Lead Beneficiary 23 BU Dissemination Level PU Change log Version Date amended by changes 1.0 26.09.2016 Hakan Yilmaz Final deliverable sent to coordinator after implementing review comments. Partners involved number partner name People involved 23 Boğaziçi University Prof. dr. Hakan Yilmaz and Çağdan Erdoğan Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... 4 PART I) MINORITIES IN TURKEY: HISTORICAL EVOLUTION AND CONTEMPORARY SITUATION ...................... 5 1) A Brief History of Minority Groups in Turkey .................................................................................... 5 2) The End of the Ottoman Millet System ............................................................................................ 5 3) Defining the Minority Groups in the Newly Emerging Nation- State ................................................ 6 4) What Happened to the Non-Muslim Population of Turkey? ............................................................. 7 5) What Happened to the Unrecognized Minorities in Turkey? .......................................................... 10 PART II) THE KURDISH QUESTION: THE PINNACLE OF THE -

FÜSUN KÖKSAL İNCİRLİOĞLU Composer Born 1973, Bursa-Turkey Currently Based in İzmir-Turkey EDUCATION 2013 Phd in Music C

FÜSUN KÖKSAL İNCİRLİOĞLU Composer Born 1973, Bursa-Turkey Currently based in İzmir-Turkey EDUCATION 2013 PhD in Music Composition. The University of Chicago 2002 Master of Music in Music Theory. Hochschule für Musik Köln 2000 Master of Music in Composition. Hochschule für Musik Köln 1996 Bachelor of Music. Bilkent University Faculty of Music and Performing Arts. Ankara WORKS: SELECTED PERFORMANCES & FESTIVALS 2020 voce immobile (2018) for solo bass clarinet. KNM Contemporaries. Horia Dumitrache. Dec. 12. Berlin. quelle'd (2020) for ensemble. Now Festival. E-Mex Ensemble. Dir. Christoph Maria Wagner. Nov. 1. Essen. String Quartet No. 1 (2006) Weekend of Chamber Music. Ciompi String Quartet. July 12. New York (postponed). Deux Visions pour sextuor (2009) for sextet. Ensemble Norbotten Neo. Feb.3. Pieta. Dances of The Black Sea (2013) for solo flute. Jennifer Lau. New Music Festival. Jan. 17. Sunny Stony Brook Univ. New York. Dances of The Black Sea (2013) for solo flute. Cem Önertürk. Jan. 11. Ankara. 2019 Dances of The Black Sea (2013) for solo flute. Cem Önertürk. Dec. 11. Bursa. Dances of The Black Sea (2013) for solo flute. Cem Önertürk. Nov. 29. İstanbul. String Quartet No. 1 (2006). Ciompi String Quartet. Nov. 24. Duke Univ. String Quartet No. 1 (2006). Ciompi String Quartet. Nov. 10. Duke Univ. String Quartet No. 1 (2006). Ciompi String Quartet. Nov. 5. Duke Univ. Silent Echoes for 32 String Instuments (2018-19). Yound Euro Classics Festival.Turkish National Youth Orchestra (TUGFO). Dir. Cem Mansur. July 24. Berlin. Silent Echoes for 32 String Instuments (2018-19). TUGFO. Dir. Cem Mansur. July 22. -

Bursa Ili, Nilüfer Ilçesi, Çali Mahallesi Çali Hidroelektrik Santral Alani

2020 BURSA İLİ, NİLÜFER İLÇESİ, ÇALI MAHALLESİ ÇALI HİDROELEKTRİK SANTRAL ALANI UYGULAMA İMAR PLANI DEĞİŞİKLİĞİ ADA: 5873 PARSEL:46 SINIR PLANLAMA LTD.ŞTİ. OCAK-2020 Kazımdirik Mahallesi 367/7 Sokak No:14 Avcılar Effect A Blok K:7 D:722 Bornova/İzmir 0232 425 05 72 – 0533 305 06 25 e-mail: [email protected] web: www.splanlama.com İÇİNDEKİLER AMAÇ, KAPSAM ve YÖNTEM 1. PLANLAMA ALANININ ÜLKE ve BÖLGESİNDEKİ YERİ ....................................... 1 2. PLANLAMA ALANINA İLİŞKİN ARAŞTIRMALAR .................................................. 3 2.1. Planlama Alanının Konumu .............................................................................. 3 2.2. Genel Arazi Kullanım-Halihazır Durum ............................................................ 4 2.2.1. İçme ve Kullanma Suyu Sağlanan Kaynaklar ............................................ 4 2.2.2. Jeomorfolojik ve Topoğrafik Eşikler ........................................................... 4 2.4. Jeolojik Durum, Deprem, Akarsular, Taşkın Durumu ....................................... 5 2.5. İklim ve Bitki Örtüsü ....................................................................................... 11 2.6. Planlama Alanı ve Çevresinin Yürürlükteki İmar Planlarındaki Durumu ......... 13 3. PLANLAMA ALANINA AİT KURUM GÖRÜŞLERİ ve KISITLILIK DURUMU ........ 15 4. DEĞERLENDİRME .............................................................................................. 24 4. PLAN KARARLARI .............................................................................................. -

Record of Myxomycetes on Monumental Trees in Bursa City Center – Turkey

RESEARCH ARTICLE Eur J Biol 2019; 78(1): 40-50 Record of Myxomycetes on Monumental Trees in Bursa City Center – Turkey Fatima Touray1 , C. Cem Ergül2 1Bursa Uludağ University, Institute of Science, Department of Biology, Bursa, Turkey 2Bursa Uludağ University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of Biology, Bursa, Turkey ORCID IDs of the authors: F.T. 0000-0003-2384-4970; C.C.E. 0000-0002-4252-3681 Please cite this article as: Touray F, Ergul CC. Record of Myxomycetes on Monumental Trees in Bursa City Center – Turkey. Eur J Biol 2019; 78(1): 40-50. ABSTRACT Objective: Urbanization has been reported to affect the biodiversity of myxomycetes. There is no data in the Bursa city on the diversity of myxomycete in the urban area. Therefore, we aim to determine the presence of corticolous myxomycetes on monumental trees that are located in the most populated province of Bursa city (Osmangazi and Yıldırım). Materials and Methods: In August and October 2018, 100 barks of monumental trees located in the Osmangazi and Yıldırım) county of Bursa was collected. Moist chamber culture technique was used for the isolation and identification of the species. Results: 16 species within 9 genera were identified. The species identified are listed, and six new species Didymium bahiense (Gottsberger), Didymium difforme (Pers.) S. F. Gray), Macbrideola martinii (Alexop. & Beneke), Macbrideola oblonga (Pando, Lado), Physarum gyrosum (Rost.), Physarum notabile (Macbr.) were recorded for Bursa city. Conclusion: This is the first report of corticolous myxomycetes on monumental trees in Bursa city center. It also added data and 6 new records of myxomycetes on the myxomycete biodiversity of Bursa. -

İstanbul-Bursa-Balıkesir-İzmir INFORMATION BULLETIN

İstanbul-Bursa-Balıkesir-İzmir INFORMATION BULLETIN 1. GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE AND CLOTHING The climate in Turkey in June is around a maximum of 22oC, a minimum of 8oC, with an average of 16oC. The mean rainfall is around 45 mm. It may be cool in the evenings, so a sweater or a light jacket is recommended. Other than that, comfortable clothing and shoes are recommended since we will be constantly moving. You may wish to bring your swim suit, at least in Karaburun (İzmir) you will have chance to swim. The traveling seminar will take participants from İstanbul to Bursa, Balıkesir and then to İzmir in 6 days, covering 611 km of road. 2. VENUE OF THE TRAINING COURSE Since this training is a traveling seminar, accommodation will be provided in a number of hotels on the way. Participants will travel during the day and sleep in a hotel in a city on route. All participants must check in at the following hotel upon arrival to Istanbul. The first meeting will be held at the hotel on at 8:00 am on Monday, June 1, 2009. All participants should note that the bus will leave the hotel in Istanbul after opening session that is 10:30am. GTN/VQ does not take any responsibility if you are late in arrival in Istanbul. Therefore it is extremely important that you check in GRAND ÖZTANIK HOTEL (****) latest on Sunday 31 May. GRAND ÖZTANIK HOTEL (****) Topçu Caddesi No: 9-11 Taksim- İstanbul Tel: +90 212 3616090 Fax: +90 212 3616078/79 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.grandoztanik.com Page 1 Pharmaceutical cold chain management on wheels, Information Bulletin 2009 Airport Please note that you will NOT be met on arrival. -

BURSA'nin İLK EDEBİYAT Ve SANAT DERGİSİ: NİLÜFER

U.Ü. FEN-EDEBİYAT FAKÜLTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER DERGİSİ Yıl: 7, Sayı: 10, 2006/1 BURSA’NIN İLK EDEBİYAT ve SANAT DERGİSİ: NİLÜFER Alev SINAR ÇILGIN* ÖZET Nilüfer, Bursa’da yayınlanan ilk edebiyat ve sanat dergisidir. Dergiyi çıkartan isim, Feraizcizade Mehmet Şakir’dir. Nilüfer dergisi 1886 - 1891 tarihleri arasında yayınlanmıştır. Memleketin farklı bölgelerinden çok sayıda şiir ve takdir ifade eden mektup gönderilen derginin sadece Bursalılar tarafından değil Osmanlı Devleti’nin sınırları içindeki diğer vilayetlerde de edebiyat meraklıları tarafından ilgiyle takip edildiği anlaşılmaktadır. Bütün meseleleri bilimin ışığında değerlendirdiğini ifade eden Nilüfer, edebî ve edep çerçevesinde yazılmış yazılara açıktır. Derginin geniş bir yazı kadrosu vardır. Edebiyat meraklılarının gönderdikleri şiirlerin yanı sıra derginin sahibi Feraizcizade Mehmet Şakir ile Recep Vahyî, Ağlarcazade Mustafa Hakkı, Hersekli Arif Hikmet gibi isimlerin eserleri yayınlanır. Bu isimlerden Recep Vahyî, Nilüfer’in keşfettiği bir kabiliyettir. Servet-i Fünûn yazarlarına etki etmiş bir isimdir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Nilüfer, Bursa, Feraizcizade Mehmet Şakir, Edebiyat, Recep Vahyi. ABSTRACT The First Art And Literature Journal Publıshed in Bursa: Nilüfer Nilüfer is the first art and literature journal published in Bursa. The name of the Publisher is Feraizcizade Mehmet Şakir and the journal has * Doç. Dr.; Uludağ Üniversitesi Fen Edebiyat Fakültesi 47 been published between the dates of 1886 and 1891. It is uderstood from the poems and letters which has been sent to the journal from different regions of the country that it was being read not only in Bursa but in all Otoman States by the people who are interested in literature. The journal is open to literary and decent essays. The journal has got a large writers staff and the works of Feraizcizade Mehmet Şakir, Ağlarcazade Mustafa Hakkı, Hersekli Arif Hikmet took place in the journal in addition to the poems sent by the amateur poets. -

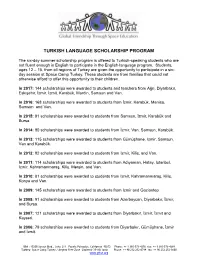

Turkish Language Scholarship Program

TURKISH LANGUAGE SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM The six-day summer scholarship program is offered to Turkish-speaking students who are not fluent enough in English to participate in the English-language program. Students, ages 12 – 15, from all regions of Turkey are given the opportunity to participate in a six- day session at Space Camp Turkey. These students are from families that could not otherwise afford to offer this opportunity to their children. In 2017: 144 scholarships were awarded to students and teachers from Ağrı, Diyarbakır, Eskişehir, İzmir, İzmit, Karabük, Mardin, Samsun and Van. In 2016: 168 scholarships were awarded to students from İzmir, Karabük, Manisa, Samsun and Van. In 2015: 91 scholarships were awarded to students from Samsun, İzmir, Karabük and Bursa. In 2014: 90 scholarships were awarded to students from İzmir, Van, Samsun, Karabük. In 2013: 115 scholarships were awarded to students from Gümüşhane, Izmir, Samsun, Van and Karabük. In 2012: 92 scholarships were awarded to students from Izmir, Kilis, and Van. In 2011: 114 scholarships were awarded to students from Adıyaman, Hatay, Istanbul, Izmir, Kahramanmaraş, Kilis, Mersin, and Van. In 2010: 81 scholarships were awarded to students from Izmir, Kahramanmaraş, Kilis, Konya and Van. In 2009: 145 scholarships were awarded to students from Izmir and Gaziantep In 2008: 91 scholarships were awarded to students from Azerbaycan, Diyarbakır, İzmir, and Bursa. In 2007: 121 scholarships were awarded to students from Diyarbakır, İzmir, İzmit and Kayseri. In 2006: 79 scholarships were awarded to students from Diyarbakır, Gümüşhane, İzmir and İzmit. USA : 15200 Sunset Blvd., Suite 211 Pacific Palisades, California 90272 Phone: ++ 1 310-573-4276 fax: ++ 1 310-573-4289 Turkey: Space Camp Turkey / Aegean Free Zone Gaziemir 35410, Izmir Phone: ++ 90 232 252-0749 fax: ++ 90 232 252-3600 www.gftse.org In 2005: 108 scholarships were awarded to students from Diyarbakır, Gümüşhane, İzmir and İzmit. -

P Evaluation Office (2011-2015)

TERMS OF REFERENCE – TURKEY INDEPENDENT CPE – EVALUATION OFFICE p Evaluation Office TERMS OF REFERENCE FOR THE EVALUATION OF THE UNFPA 5TH COUNTRY PROGRAMME OF ASSISTANCE TO THE GOVERNMENT OF TURKEY (2011-2015) 1. INTRODUCTION The Evaluation Office is planning to conduct the independent evaluation of the UNFPA 5th Country Programme of Assistance to the Government of Turkey in 2014 as part of its annual work plan, and in accordance with the UNFPA 2013 evaluation policy (DP/FPA/2013/5). As per the evaluation policy, evaluation at UNFPA serves three main purposes: (i) demonstrate accountability to stakeholders on performance in achieving development results and on invested resources; (ii) support evidence-based decision-making; (iii) contribute important lessons learned to the existing knowledge base on how to accelerate implementation of the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD). The evaluation will be managed by the Evaluation Office and conducted by a team of independent evaluators, in close cooperation with the UNFPA country office (CO) monitoring and evaluation (M&E) focal point and the Eastern Europe and Central Asia regional office (EECARO) M&E adviser. 2. CONTEXT UNFPA Assistance to Turkey is subject to the provisions of the Revised Standard Agreement (RSA) signed between United Nations and the Government of Turkey in October 1965 and ratified by the Government of Turkey in 2000. The RSA applies to UNFPA activities and personnel, mutatis mutandis, in accordance with the Letter of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkey dated 29 December 1999 ref. No CEGY/II-4297. Thus, the UNDP Standard Basic Assistance Agreement and the above Letter constitute the legal basis for the relationship between the Government of Turkey and UNFPA.