0137142447 Sample.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovation Is P&G's Life Blood

Innovation is P&G Innovations P&G’s Life Blood It is the company’s core growth strategy and growth engine. It is also one of the company’s five core strengths, outlined for focus and investment. Innovation translates consumer desires into new products. P&G’s aim is to set the pace for innovation and the benchmark for innovation success in the industry. In 2008, P&G had five of the top 10 new product launches in the US, and 10 of the top 25, according to IRI Pacesetters, a report released by Information Resources, Inc., capturing the most successful new CPG products, as measured by sales, over the past year. Over the past 14 years, P&G has had 114 top 25 Pacesetters—more than our six largest competitors combined. PRODUCT INNOVATION FIRSTS 1879 IVORY First white soap equal in quality to imported castiles 1901 GILLETTE RAZOR First disposable razor, with a double-edge blade, offers alternative to the straight edge; Gillette joins P&G in 2005 1911 CRISCO First all-vegetable shortening 1933 DREFT First synthetic household detergent 1934 DRENE First detergent shampoo 1946 TIDE First heavy-duty The “washday miracle” is introduced laundry detergent with a new, superior cleaning formula. Tide makes laundry easier and less time-consuming. Its popularity with consumers makes Tide the country’s leading laundry product by 1949. 1955 CREST First toothpaste proven A breakthrough-product, using effective in the prevention fluoride to protect against tooth of tooth decay; and the first decay, the second most prevalent to be recognized effective disease at the time. -

2006 Annual Report Financial Highlights

2006 Annual Report Financial Highlights FINANCIAL SUMMARY (UNAUDITED) Amounts in millions, except per share amounts; Years ended June 30 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 Net Sales $68,222 $56,741 $51,407 $43,377 $40,238 Operating Income 13,249 10,469 9,382 7,312 6,073 Net Earnings 8,684 6,923 6,156 4,788 3,910 Net Earnings Margin 12.7% 12.2% 12.0% 11.0% 9.7% Basic Net Earnings Per Common Share $2.79 $ 2.70 $ 2.34 $ 1.80 $ 1.46 Diluted Net Earnings Per Common Share 2.64 2.53 2.20 1.70 1.39 Dividends Per Common Share 1.15 1.03 0.93 0.82 0.76 NET SALES OPERATING CASH FLOW DILUTED NET EARNINGS (in billions of dollars) (in billions of dollars) (per common share) 68.2 11.4 2.64 4 0 4 0 4 4 40 0 0 04 0 06 0 0 04 0 06 0 0 04 0 06 Contents Letter to Shareholders 2 Capability & Opportunity 7 P&G’s Billion-Dollar Brands 16 Financial Contents 21 Corporate Officers 64 Board of Directors 65 Shareholder Information 66 11-Year Financial Summary 67 P&GataGlance 68 P&G has built a strong foundation for consistent sustainable growth, with clear strategies and room to grow in each strategic focus area, core strengths in the competencies that matter most in our industry, and a unique organizational structure that leverages P&G strengths. We are focused on delivering a full decade of industry-leading top- and bottom-line growth. -

409 Carpet Cleaner 7Th Gen Wipes Refill 7Th Generation Dish Powder

409 Carpet Cleaner 7th Gen Wipes Refill 7th Generation Dish Powder 7th Generation Fabric Soft 7th Generation Laundry A Ben A Qui Scrubbing Cream A&H Carpet Fresh Powder A&H Clean Shower Ammonia Lemon Better Life Cleansing Scrubber Better Life Dish Soap Better Life Floor Cleaner Better Life Sage Citrus Lotion Better Life Tub/Tile Cleaner Better Life Wipes Peppermint Better Life Wood Polish BioKleen Bleach Alternative (powder) BioKleen Laundry (liquid) Bounce Sheets Cascade Action Pacs Cascade Gel Cascade Powder Citrus Magic Solid Citrus Magic Tropical Citrus Clorox Bleach 30oz Clorox Bleach 64oz Comet Bathroom Cleaner Comet Powder Dawn Dish Orig Liquid Dove White Bath Soap 2 Pack Downy Mountain Spring Easy Off Oven Cleaner Febreze X Strength 16.9oz Glass Plus Handmade VT Soap Irish Spring 3pack Ivory Snow Liquid 2X Joy Dish Soap Liquid Plumber Drain Cleaner Lysol Toilet Bowl Cleaner Method All Purpose Grapefruit Method All Purpose Lavender Method Dish Liquid Lemon Method Dish Soap Method Hand Wash PG MR Clean Magic Eraser Murphy Oil Soap Natures Miracle Stain/Odor Remover O-Cel-O Med 2 Sponges Pine Sol 24oz RESOLVE CARPET CLNR TRIGR Sanitizing Wipes Bathroom Shout Stain Remover Trigger SIMPLE GREEN CLEANER Soft Scrub w/ bleach Soft Soap With Aloe SOS Scrubber Heavy Duty SOS Soap Pads SPIC & SPAN CLEANER Static Guard 5.5oz Sun & Earth Stain Pen Sun & Earth Travel Kit Swiffer Cloth Refill Swiffer Duster Refill Tide HE 50 oz. TIDE LIQ ULTRA REG Tide Pods Original Tide to Go Toilet Duck Cleaner Windex Original . -

An Example of Open Innovation: P&G

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 195 ( 2015 ) 1496 – 1502 World Conference on Technology, Innovation and Entrepreneurship An Example of Open Innovation: P&G Nesli Nazik Ozkan* Istanbul University, Faculty of Economy, Istanbul Abstract Open innovation, also known as crowdsourcing or co-creation, is a way for companies to utilize the ideas and strength of the people outside their organization to make improvements in the internal processes or products. Many companies seek input from those people outside their organization for solving some of their trickiest problems. Open innovation help them to drive employee productivity, customer loyalty and better innovation. Open innovation process consists of three main steps. These are concept phase, development phase and implementation phase. In the concept phase, research activities are carried out. In the development phase, skills are defined and projects are developed. In the implementation phase projects are implemented and exchange of information is accelerated. P&G leads the companies who applied concept of open innovation successfully in the world. Procter & Gamble Co. as the world’s 40th biggest and 84th innovative company created the web site for this propose which is known Connect + Develop to encourage open innovation to help them to drive employee productivity. P&G's open innovation strategy has enabled to establish more than 2,000 successful agreements with innovation partners around the world. C+D already has delivered strategic value all across the company, and a series of game-changing consumer innovations. -

GWK01123 Greenworks Liquid Dish Soap Original • 98% Naturally

GWK01064 GWK01123 GWK01155 Greenworks All Purpose Greenworks Liquid Dish Soap Greenworks Naturally Derived Compostable Cleaner Original Cleaning Wipes • Powers through grease, • 98% naturally derived • Cleans grease, grime and dirt with the grime and dirt • Cuts through grease and convenience of a wipe • Safe to use on multiple baked‐on foods • Compostable cleaning wipes made with naturally surfaces throughout kitchens • Leaves a streak‐free shine derived ingredients • 99% naturally derived and bathrooms, including • Non abrasive • Works on grease, grime and dirt throughout stainless steel, sealed granite • Dermatologist tested bathrooms, kitchens, breakrooms, office surfaces and chrome • 98% naturally 650 mL 12/Case and counters 62 wipes/can derived 6/Case 946mL 12/Case CLO01169 CLO01537 Clorox Fresh Scent Disinfecting Clorox Urine Remover Wipes • Specially formulated to • One‐step disinfecting and effectively remove urine cleaning LPL01165 stains while neutralizing • Health Canada registered to Liquid Plumr Full Uric Acid Crystals to kill 11 pathogens in 4 minutes Clog Remover eliminate odour including E.coli and Influenza A • Unique formula goes • Exceptional cleaning • Sanitizes hard non‐porous straight to the clog performance on tough stains surfaces in 30 seconds • Active ingredients dissolve including urine, bodily fluids • Ready to use, pre‐moistened hair and food soils, and create and wine wipes free‐flowing drains • Can be used to clean both • Bleach‐free formula! • CFIA • Safe for disposals, septic hard and soft surfaces such -

Rebate Check by Mail with a Minimum 5 Case Purchase

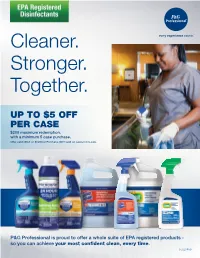

Cleaner. Stronger. Together. UP TO $5 OFF PER CASE $200 maximum redemption, with a minimum 5 case purchase. Offer valid ONLY on End User Purchase, NOT valid on cases for re-sale. P&G Professional is proud to offer a whole suite of EPA registered products - so you can achieve your most confident clean, every time. © 2020 P&G Receive a P&G Professional rebate check by mail with a minimum 5 case purchase. UP TO Offer valid between 7/1/2020 and 9/30/2020. To learn more, please call 1-800-332-7787. Visit pgpro.com or contact your $5 OFF P&G Professional representative today. PER CASE Offer valid ONLY on End User Purchase, NOT valid on cases for re-sale $200 maximum redemption REBATE FORM—NOT PAYABLE AT RETAIL By registering, I agree to receive emails from P&G Professional. View full P&G Terms and Conditions at http://www.pg.com/privacy/english/privacy_statement.html HOW TO GET YOUR REBATE: PLEASE MAIL P&G PROFESSIONAL REBATE #21145 TO THE FOLLOWING PAYEE: 1 BUY at least 5 cases (mix and match) of any of the Bounty, Charmin, Dawn, Spic and Span, Comet, Mr. Clean, Febreze, Microban, or Swiffer products listed in the chart below ALL SHADED FIELDS MUST BE COMPLETED FULLY TO RECEIVE REBATE between 7/1/2020 and 9/30/2020 2 SCAN Request Form and proof of purchase** and EMAIL to [email protected] before 11/30/2020 BUSINESS NAME (PAYEE) OR mail original Request Form, and proof of purchase,** dated with postmark before 11/30/2020 Jul.-Sept. -

“The Jensen Project” Follows on the Success of P&G's and Walmart's First Made-For-TV Movie

In response to research indicating parents are looking for more family- oriented entertainment, Procter & Gamble and Walmart are bringing back Family Movie Night with the premier of their second made-for-TV movie: “The Jensen Project.” According to research from the ANA’s Alliance for Family Entertainment, only 23% of respondents were satisfied with the amount of family-oriented programming available. Advertising appearing in a family- friendly context is much more effective in reaching consumers. “The Jensen Project” follows on the success of P&G’s and Walmart’s first made-for-TV movie, “Secrets of the Mountain,” which aired in April 2010: • “Secrets of the Mountain” generated more than • Following in the footsteps of that first movie, one billion impressions, resulting in 7.5 million “The Jensen Project” will include co-advertising viewers and a 4.5 television household rating. between Walmart and P&G featuring a single The movie was the #1 show of the night and family creating “family moments” that has proven claimed NBC’s top spot for the week, beating first to increase trip and purchase intent. So while run episodes of “The Biggest Loser,” “Parenthood” families are enjoying the movie, they’ll be seeing and “The Celebrity Apprentice.” “Secrets of the inspiring co-advertising vignettes featuring Swiffer, Mountain” was also the #1 Friday movie of the Charmin, Tide, Iams, Pampers, Bounty, and year, beating network premiers of box office hits regimens for Gillette shaving, Crest 3D White, and “Shrek The Third” and “Ice Age 2: The Meltdown.” P&G Beauty (Pantene, Covergirl, Olay). latest innovations pginnovation.com About “The Jensen Project”: Air & Release Dates: “The Jensen Project” is supported with a fully “The Jensen Project” will air Friday, July 16, 2010 at integrated marketing plan designed to create an 8 PM Eastern/7 PM Central on NBC. -

Annual Report Table of Contents

2018 Annual Report Table of Contents Letter to Shareowners i Company and Shareholder Information 75 Five Measures of Noticeable Superiority iv Company Leadership 76 P&G’s 10-Category Portfolio xii Board of Directors 77 Form 10-K xiii Recognition and Commitments 78 Measures Not Defined Citizenship Inside Back Cover by U.S. GAAP 74 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS (UNAUDITED) Amounts in billions, except per share amounts 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 Net Sales $66.8 $65.1 $65.3 $70.7 $74.4 Operating Income $13.7 $14.0 $13.4 $11.0 $13.9 Net Earnings Attributable to P&G $9.8 $15.3 $10.5 $7.0 $11.6 Net Earnings Margin from Continuing Operations 14.8% 15.7% 15.4% 11.7% 14.3% Diluted Net Earnings per Common Share from Continuing Operations 1 $3.67 $3.69 $3.49 $2.84 $3.63 Diluted Net Earnings per Common Share 1 $3.67 $5.59 $3.69 $2.44 $4.01 Operating Cash Flow $14.9 $12.8 $15.4 $14.6 $14.0 Dividends per Common Share $2.79 $2.70 $2.66 $2.59 $2.45 2018 NET SALES BY 2018 NET SALES BY 2018 NET SALES BY BUSINESS SEGMENT 2 GEOGRAPHIC REGION MARKET MATURITY Beauty 19% North America 3 44% Developed Markets 65% Grooming 10% Europe 24% Developing Markets 35% Health Care 12% Asia Pacific 9% Fabric & Home Care 32% Greater China 9% Baby, Feminine & Family Care 27% Latin America 7% India, Middle East & Africa (IMEA) 7% (1) Diluted net earnings per common share are calculated based on net earnings attributable to Procter & Gamble. -

Stock up Price List Beauty, Health, and Baby

STOCK UP PRICE LIST BEAUTY, HEALTH, AND BABY PAGES 3–12 GROCERY PAGES 13–25 LAUNDRY, PLASTICS, HOUSEHOLD, AND EVERYTHING ELSE PAGES 26–30 STOCK UP PRICE LIST BEAUTY, HEALTH, AND BABY STOCK UP PRICE LIST THE KRAZY COUPON LADY STOCK UP PRICE LIST BEAUTY, HEALTH, AND BABY Diapers 3 Month 6 Month Baby Cereal 3 Month 6 Month Price Price Price Price Huggies Jumbo Pack $4.00 $3.00 Gerber 8 oz $1.99 $0.99 Pampers Jumbo Pack $5.00 $4.00 Earth's Best 8 oz $1.99 $0.99 Seventh Generation Jumbo Pack $6.00 $5.00 Happy Baby 7 oz $1.99 $0.99 Honest Company Jumbo Pack $6.00 $5.00 Beech-Nut 8 oz $0.99 Free Store Brand Jumbo Pack $3.00 $1.99 Baby Food Pouches 3 Month 6 Month Price Price Baby Wipes 3 Month 6 Month Plum Organics 4 oz $0.75 $0.25 Price Price Happy Baby 4 oz $0.75 $0.25 Huggies 56 CT $0.99 $0.50 Ellas Kitchen $0.75 $0.25 Pampers 56 CT $1.49 $0.99 Gerber 3.5 oz $0.50 $0.25 Seventh Generation 64 CT $1.99 $0.99 Earths Best 3.5-4 oz $0.50 $0.25 Honest Company $1.99 $0.99 Kandoo Wipes 42 CT $0.50 Free Baby/Kids Body Care 3 Month 6 Month Wet Ones 40 CT $0.99 $0.49 Price Price Aveeno Baby Wash and Shampoo $2.50 $1.00 8 oz Baby Food Jars 3 Month 6 Month Aquaphor Baby Healing Ointment $3.75 $2.00 Price Price 3 oz Gerber 4 oz 2 CT $0.50 $0.25 Cetaphil Baby Wash 8 oz $2.50 $1.00 Earth's Best 4 oz $0.25 Free Johnson’s Baby Lotion 9 oz $1.50 $0.99 Beech-Nut Jars 4 oz $0.25 Free Johnson’s Baby Powder 15 oz $1.50 $0.80 Beech-Nut Naturals 4.25 oz $0.50 Free 4 THE KRAZY COUPON LADY STOCK UP PRICE LIST BEAUTY, HEALTH, AND BABY (CONTINUED) Baby/Kids Body Care 3 Month 6 Month Body Wash (Continued) 3 Month 6 Month (Continued) Price Price Price Price Johnson’s Baby Shampoo 15 oz $1.50 $0.99 Suave Naturals 15 oz $0.49 Free Johnson’s Head to Toe Baby Wash $1.50 $0.99 Aveeno Body Wash 12 oz $2.99 $2.49 15 oz Boudreaux Diaper Rash Ointment $1.00 Free Irish Springs Body Wash 18 oz $1.99 $1.49 2 oz Desitin Original Paste 2 oz $2.00 $1.50 St. -

How to Clean Your Hardwood Floors

7/13/2015 How to Clean Your Hardwood Floors Floors Housekeeping Most Popular How to Clean Your Hardwood Floors Gleaming wood floors are a thing of beauty. Here’s how to keep them that way Bonnie McCarthy Houzz Contributor. Style anthropologist, freelance writer and photographer... More 2 Email What are you working on? Comment 274 Like 513 Bookmark 2k+ Print Embed Siding & Trim Color to Coordinate with Brick Click "Embed" to display an article on your own website or blog. 1 lthough installing hardwood flooring is usually more expensive than rolling out new carpet, it’s an investment worth considering, according to data from the National A Desperate for Curb Appeal Association of Realtors. Surveys show that 54 percent of home buyers are willing to 3 pay more for a house with hardwood floors. The question now: What’s the best way to clean and care for that popular flooring and keep that natural beauty (and value) shining through? Here’s how. See all Design Dilemmas 2 It’s not the wood — oak, Gast Architects 2 maple, mesquite, bamboo, News From Our Partners engineered hardwood or This HGTV Host Just Took the First something more exotic — Dance to a Whole New Level that determines how the Homespun Heirloom Kitchen floors should be cleaned, but 8 Projects to Renew Every Room in Your Home rather the finish. 7 must-haves for Scandinavian style People who liked this story also liked Houzz Guide: How to Set a Table Full Story 2 Lush Gardens With Low Water Needs Full Story 2 Shower Design: 13 Tricks With Tile and Other Materials Full -

P&G Was Established in Germany in 1960. What Started with a Few

Germany Established: 1960 Employees: More than 9,000 Legal Entities: Procter & Gamble Germany GmbH Procter & Gamble Germany GmbH & Co Operations oHG Procter & Gamble Deutschland GmbH Procter & Gamble Service GmbH Braun GmbH Procter & Gamble Manufacturing Berlin GmbH Procter & Gamble Holding GmbH Procter & Gamble GmbH Procter & Gamble Manufacturing GmbH Procter & Gamble Health Germany GmbH Procter & Gamble Consumer Health Germany GmbH Procter & Gamble Grundstücks- und Vermögensverwaltungs GmbH & Co. KG WEBA Betriebsrenten-Verwaltungsgesellschaft mbH P&G Health Austria GmbH & Co. OG Procter & Gamble GmbH - Austria Sites: 11 sites Administration: Schwalbach, Darmstadt (P&G Health Germany GmbH) Innovation Centers: Schwalbach, Kronberg Plants: Berlin, Crailsheim, Euskirchen, Groß Gerau, Marktheidenfeld, Walldürn, Worms Distribution Centers: Altfeld, Crailsheim, Euskirchen Brands: Beauty: Head & Shoulders, Olay, Herbal Essences, Pantene, Old Spice Grooming: Braun, Gillette, Gillette Venus Baby & Feminine Care: Pampers, Always, Always Discreet Oral Care: Oral-B, Blend-a-dent, Blend-a-med Health Care: Wick, Clearblue, Persona, Nasivin, Femibion, Cebion, Bion 3, Vigantol, Neurobion, Dolo-Neurobion, Kytta, Kytta Sedativum, Household Care: Ariel, Lenor, Meister Proper, Febreze, Swiffer, Antikal, Fairy P&G was established in Germany in 1960. What started with a few employees in a small office in downtown Frankfurt has become the largest research & development center for P&G outside the U.S. with around 750 employees. Germany is also one of the biggest production locations outside the U.S. Today, approximately 9,000 employees work for P&G in Germany. Key Facts • In Germany P&G brands have delighted • In our German Innovation Center research is consumers for more than 50 years. About 30 P&G conducted in the areas of Baby Care, Feminine brands are available in Germany. -

US EPA, Pesticide Product Label, Trilambda AB,11/04/2019

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY EPA Reg. Number: Date of Issuance: Office of Pesticide Programs Antimicrobials Division (7510P) 3573-102 11/4/19 1200 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20460 NOTICE OF PESTICIDE: Term of Issuance: X Registration Reregistration Conditional (under FIFRA, as amended) Name of Pesticide Product: TriLambda AB Name and Address of Registrant (include ZIP Code): Teresa Moore Proctor & Gamble Company 5299 Spring Grove Avenue Cincinnati, OH 45217 Note: Changes in labeling differing in substance from that accepted in connection with this registration must be submitted to and accepted by the Antimicrobials Division prior to use of the label in commerce. In any correspondence on this product always refer to the above EPA registration number. On the basis of information furnished by the registrant, the above named pesticide is hereby registered under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act. Registration is in no way to be construed as an endorsement or recommendation of this product by the Agency. In order to protect health and the environment, the Administrator, on his motion, may at any time suspend or cancel the registration of a pesticide in accordance with the Act. The acceptance of any name in connection with the registration of a product under this Act is not to be construed as giving the registrant a right to exclusive use of the name or to its use if it has been covered by others. This product is conditionally registered in accordance with FIFRA section 3(c)(7)(A). You must comply with the following conditions: 1. Submit and/or cite all data required for registration/reregistration/registration review of your product under FIFRA when the Agency requires all registrants of similar products to submit such data.