PUD No. 1 of Jefferson County V. Washington Department of Ecology: State Water Quality Certification of Ederf Ally Licensed Hydropower Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jefferson County Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment 2011 2

Jefferson County Department of Emergency Management 81 Elkins Road, Port Hadlock, Washington 98339 - Phone: (360) 385-9368 Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 I. INTRODUCTION 6 II. GEOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS 6 III. DEMOGRAPHIC ASPECTS 7 IV. SIGNIFICANT HISTORICAL DISASTER EVENTS 9 V. NATURAL HAZARDS 12 • AVALANCHE 13 • DROUGHT 14 • EARTHQUAKES 17 • FLOOD 24 • LANDSLIDE 32 • SEVERE LOCAL STORM 34 • TSUNAMI / SEICHE 38 • VOLCANO 42 • WILDLAND / FOREST / INTERFACE FIRES 45 VI. TECHNOLOGICAL (HUMAN MADE) HAZARDS 48 • CIVIL DISTURBANCE 49 • DAM FAILURE 51 • ENERGY EMERGENCY 53 • FOOD AND WATER CONTAMINATION 56 • HAZARDOUS MATERIALS 58 • MARINE OIL SPILL – MAJOR POLLUTION EVENT 60 • SHELTER / REFUGE SITE 62 • TERRORISM 64 • URBAN FIRE 67 RESOURCES / REFERENCES 69 Jefferson County Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment 2011 2 PURPOSE This Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment (HIVA) document describes known natural and technological (human-made) hazards that could potentially impact the lives, economy, environment, and property of residents of Jefferson County. It provides a foundation for further planning to ensure that County leadership, agencies, and citizens are aware and prepared to meet the effects of disasters and emergencies. Incident management cannot be event driven. Through increased awareness and preventive measures, the ultimate goal is to help ensure a unified approach that will lesson vulnerability to hazards over time. The HIVA is not a detailed study, but a general overview of known hazards that can affect Jefferson County. Jefferson County Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment 2011 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An integrated emergency management approach involves hazard identification, risk assessment, and vulnerability analysis. This document, the Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Assessment (HIVA) describes the hazard identification and assessment of both natural hazards and technological, or human caused hazards, which exist for the people of Jefferson County. -

Salmon and Steelhead Habitat Limiting Factors

SALMON AND STEELHEAD HABITAT LIMITING FACTORS WATER RESOURCE INVENTORY AREA 16 DOSEWALLIPS-SKOKOMISH BASIN Hamma Hamma River, Ecology Oblique Photo, 2001 WASHINGTON STATE CONSERVATION COMMISSION FINAL REPORT Ginna Correa June 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The WRIA 16 salmon habitat limiting factors report could not have been completed without considerable contributions of time and effort from the following people who participated in various capacities on the technical advisory group (TAG): Charles Toal, Washington Department of Ecology Doris Small, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Herb Cargill, Washington Department of Natural Resources Jeff Davis, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Jeff Heinis, Skokomish Tribe John Cambalik, Puget Sound Action Team Marc McHenry, US Forest Service Margie Schirato, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Marty Ereth, Skokomish Tribe Randy Johnson, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Richard Brocksmith, Hood Canal Coordinating Council Steve Todd, Point No Point Treaty Council In addition, the author also wishes to thank the following for extensive information regarding fish populations and habitat conditions and substantial editorial comments during development of the report: Dr. Carol Smith, WCC for the Introduction chapter of this report; Carol Thayer, WDNR, for extensive GIS analysis of DNR ownership; Carrie Cook-Tabor, USFWS, for data contribution on the Hamma Hamma; Denise Forbes, Mason County Public Works, for the county perspective on the Skokomish; Ed Manary, WCC, for his guidance -

Geologic Map of Washington - Northwest Quadrant

GEOLOGIC MAP OF WASHINGTON - NORTHWEST QUADRANT by JOE D. DRAGOVICH, ROBERT L. LOGAN, HENRY W. SCHASSE, TIMOTHY J. WALSH, WILLIAM S. LINGLEY, JR., DAVID K . NORMAN, WENDY J. GERSTEL, THOMAS J. LAPEN, J. ERIC SCHUSTER, AND KAREN D. MEYERS WASHINGTON DIVISION Of GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGIC MAP GM-50 2002 •• WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF 4 r Natural Resources Doug Sutherland· Commissioner of Pubhc Lands Division ol Geology and Earth Resources Ron Telssera, Slate Geologist WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Ron Teissere, State Geologist David K. Norman, Assistant State Geologist GEOLOGIC MAP OF WASHINGTON NORTHWEST QUADRANT by Joe D. Dragovich, Robert L. Logan, Henry W. Schasse, Timothy J. Walsh, William S. Lingley, Jr., David K. Norman, Wendy J. Gerstel, Thomas J. Lapen, J. Eric Schuster, and Karen D. Meyers This publication is dedicated to Rowland W. Tabor, U.S. Geological Survey, retired, in recognition and appreciation of his fundamental contributions to geologic mapping and geologic understanding in the Cascade Range and Olympic Mountains. WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGIC MAP GM-50 2002 Envelope photo: View to the northeast from Hurricane Ridge in the Olympic Mountains across the eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca to the northern Cascade Range. The Dungeness River lowland, capped by late Pleistocene glacial sedi ments, is in the center foreground. Holocene Dungeness Spit is in the lower left foreground. Fidalgo Island and Mount Erie, composed of Jurassic intrusive and Jurassic to Cretaceous sedimentary rocks of the Fidalgo Complex, are visible as the first high point of land directly across the strait from Dungeness Spit. -

NMFS. 2016. Puget Chinook, Hood Canal Summer-Run

Science, Service, Stewardship 2016 5-Year Review: Summary & Evaluation of Puget Sound Chinook Salmon Hood Canal Summer-run Chum Salmon Puget Sound Steelhead National Marine Fisheries Service West Coast Region Portland, OR U.S. Department of Commerce I National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration I National Marine Fisheries Service This page intentionally left blank 5-Year Review: Puget Sound NOAA Fisheries 5-Year Review: Puget Sound Species Species Reviewed Evolutionarily Significant Unit or Distinct Population Segment Chinook Salmon Puget Sound Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) Chum Salmon Hood Canal Summer-run Chum Salmon (O. keta) Steelhead Puget Sound Steelhead (O. mykiss) i 5-Year Review: Puget Sound NOAA Fisheries This page intentionally left blank ii 5-Year Review: Puget Sound NOAA Fisheries Table of Contents 1 ∙ GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Background on listing determinations .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 METHODOLOGY USED TO COMPLETE THE REVIEW ............................................................................................................ 2 1.3 BACKGROUND – SUMMARY OF PREVIOUS REVIEWS, STATUTORY AND REGULATORY ACTIONS, AND -

Dosewallips River Powerlines Reach Restoration Project

Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 Public Law 110-343 Title II Project Submission Form USDA Forest Service Name of Resource Advisory Committee: Olympic Peninsula Project Number (Assigned by Designated Federal Official): Funding Fiscal Year(s): 2019-22 2. Project Name: Dosewallips River Powerlines 3a. State: Washington Reach Restoration Project 3b. County(s): Jefferson 4. Project Submitted By: Tami Pokorny, Jefferson 5. Date: 01/31/2019 County Environmental Public Health natural resources program coordinator 6. Contact Phone Number: 360/379-4498 7. Contact E-mail: [email protected] 8. Project Location: Dosewallips River RM 1.3-2.5 a. National Forest(s): Olympic NF is b. Forest Service District: Hood Canal upstream c. Location (Township-Range-Section) Sec. 34, T26 N, R 2W 9. Project Goals and Objectives: To improve floodplain and channel migration processes on the Dosewallips River in the largely protected Powerlines Reach by developing a preliminary design for high value restoration actions. These actions will improve floodplain conditions by restoring habitat structure and complexity to modified portions of the reach to benefit spawning and incubating of Hood Canal Summer Chum salmon. The design will be selected in consultation with a technical group convened by the County to include representation from the Lazy C and Brinnon communities. This SRS Title II request is needed to match a portion of RCO Salmon Recovery Funding Board grant #18-1228. The project’s objectives are to: i. Provide for regular communication and open exchange of ideas among project consultants, partners, landowners, and other community members. -

Geologic Map GM-57, Geologic Map of the Port Townsend North And

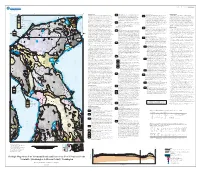

WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGIC MAP GM-57 122°52¢30² R2W R1W 50¢ 47¢30² 122°45¢ GEOLOGIC SETTING Landslide deposits—Gravel, sand, silt, clay, and boulders; clasts angular to Deposits of the Possession Glaciation ACKNOWLEDGMENTS modified from G. W. Thorsen (written Qls commun., 2004) and Easterbrook (1994) 1 rounded; unsorted; generally loose, unstratified, broken, and chaotic, but may Lower to middle Eocene Crescent Formation basaltic rocks form the basement for the Possession Drift (columnar sections and cross section only)—Glaciomarine This map was produced in cooperation with the U.S. Geological Survey National locally retain primary bedding structure; may include liquefaction features; Qgp 0–15 ft Qml till (regraded) northeastern Olympic Peninsula and are the oldest rocks exposed in the map area (Tabor and p drift and underlying till; distinguished from equivalent Vashon facies by Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program, Agreement Number 04HQAG0069, which partially 15–30 ft Qgt Qb Qc Qd Qf deposited by mass wasting processes other than soil creep and frost heave; Vashon till Qguc w Qf Cady, 1978). They consist mostly of columnar to massive flows with oxidized tops and stratigraphic position. Glaciomarine drift facies variegated; typically clay and silt- supported our mapping project. We thank Gerald W. Thorsen for extensive geologic advice, Qmw typically in unconformable contact with surrounding units. Scarps are shown Qd locally developed paleosols overlain by basaltic cobble to boulder conglomerate. rich diamicton; buff, gray, to dark gray; compact and commonly with vertical site-specific and general expertise, field trips, radiocarbon age data, and review of map and Vashon advance Qml Qguc where supported by lidar (light distance and ranging, based on airborne laser ~35 ft Qga outwash sand Qgo Qgt Qb The rocks of the Crescent Formation are overlain by an unnamed sandstone and siltstone desiccation cracks and shells; locally indistinguishable from till. -

Flattery Rocks National Wildlife Refuge

nacortes-Friday H A arbor Ferry Pe ar P oi FFrriiddaayynt Harbor y Harbor Ba r e n t a n m e r C e h s i F AAnnaaccoorrtteess 124°0'0"W 123°0'0"W n Tillicum k i l 1a a c pl 17 nd k U a ³² 1a a s c Belmont ³² r b P k a ³² p Glen J Park m y u Lake Ba * H " Luxton West Bay Y Colwood T Braemar James A Happy N Heights VViiccttoorriiaa D Bay Iceberg Valley A U t 1 Poin ³² N O S A C C Chibahdehl N Tatoosh Mushroom Slant Rocks Kydikabbit A Island U Rock Rock MIIDDWAAYY Point Koitlah British Columbia British Columbia J y Cr a Point anb Sah-da-ped-thl Warmhouse err B N y L Look- t a n k t Titacoclos CLASSET Beach Waadah i A e Through Rock CLASSET Po Albert ne Falls Island S or Cape r Head C Fuca t e Kan Archawat t gar Pillar Flattery First t oo Peak O in NEEAH Beach Second s (1308'') Bahokus re t o V C ek BAY Beach h Troxell il lage BAY Third n Peak i c W d Beach o t (1380'') R P e a B Av S A N J Y a y a w y M U A N C O U N T t r y Vie k c e c o Y IS h t T L A N C r R N D C O U N T Y t S U a ucket o O Y e d o T r l E ke C N e 14 ell ape F C N U Trox k C ³² A O re J U C e N O N W WAAAATTCCHH k S A R S d hi d Waatch F E N dbey Isla n Point E F n AS ad Hobuck J r ost Y F Beach Hobuck k a u r o Lake T e e C L C o l A y Bahobohosh r Y C A N N L A a Point L D T S T Waatch n A M A U ek a k N e O r Peak e C t ml re O Y n l M a C U T U C i Strawberry (1350') a d N C (1350') ka In u e h J N U n e T O O Fakkema B Rock R on s a Shipwreck Y N C T Y g es ati n N N e v C n r s s A e U n i U e u Point J C O d O u l N M S an J u an I sla nd s Silver Lake Sooes -

Dosewallips State Park Area Management Plan

Dosewallips State Park Area Management Plan Approved June 2006 Washington State Parks Mission The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission acquires, operates, enhances, and protects a diverse system of recreational, cultural, and natural sites. The Commission fosters outdoor recreation and education statewide to provide enjoyment and enrichment for all and a valued legacy to future generations. WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSION Washington State Parks Classification and Management Planning Project ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND CONTACTS The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission gratefully acknowledges the many stakeholders and the staff of Dosewallips State Park who participated in public meetings, reviewed voluminous materials, and made this a better plan because of it. Plan Author Lisa Lantz, Southwest Region Resource Steward Dosewallips State Park Area Management Planning Team Peter Herzog, CAMP Project Lead Doug Hinton, Dosewallips State Park Area Manager Lisa Lantz, Southwest Region Resource Steward Kelli Burke, Environmental Specialist Selma Bjarnadottir, Parks Planner Paul Malmberg, Southwest Region Manager Mike Sternback – Southwest Region Assistant Manager – Programs and Services Deborah Petersen, Environmental Planner Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission 7150 Cleanwater Lane, P.O. Box 42650 Olympia, WA 98504-2650 Tel: (360) 902-8500 Fax: (360) 753-1594 TDD: (360) 664-3133 Commissioners (at time of land classification adoption): Clyde Anderson Mickey Fearn Bob Petersen Eliot Scull Joe Taller -

WRIA 18 Salmonid Habitat Limiting Factors Analysis

SALMON AND STEELHEAD HABITAT LIMITING FACTORS WATER RESOURCE INVENTORY AREA 18 WASHINGTON STATE CONSERVATION COMMISSION FINAL REPORT Donald Haring 12/27/99 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this report would not have been possible without the support and cooperation of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG). Their expertise and familiarity with the sub-watersheds within Water Resource Inventory Area (WRIA) 18, and their interest and willingness to share their knowledge, allowed us to complete this report. Two TAGs, one for the Dungeness Watershed (Bell Creek to Bagley Creek), and one for Morse Creek to the Elwha River, were utilized through much of the information collection phase of report development, with several of the members participating in both groups. The TAG participants from both groups are consolidated in the following list: Kevin Bauersfeld Department of Fish and Wildlife Lloyd Beebe Resident, owner of Olympic Game Farm Walt Blendermann Resident, City of Sequim John Cambalik North Olympic Lead Entity Coordinator Randy Cooper Department of Fish and Wildlife Pat Crain Elwha Klallam Tribe Steve Evans Department of Fish and Wildlife Joel Freudenthal Clallam County Dick Goin Resident, City of Port Angeles Mark Haggerty U.S. Forest Service Paul Hansen Clallam Conservation District Donald Haring Conservation Commission Randy Johnson Department of Fish and Wildlife Ray Johnson Department of Fish and Wildlife Eloise Kallin Protect the Peninsula’s Future Mike McHenry Elwha Klallam Tribe Cynthia Nelson Department of Ecology Linda Newberry -

Identifying Historical Populations of Steelhead Within the Puget Sound Distinct Population Segment Doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-128

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-128 Identifying Historical Populations of Steelhead within the Puget Sound Distinct Population Segment doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-128 March 2015 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Northwest Fisheries Science Center NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC Series The Northwest Fisheries Science Center of NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC series to issue scientific and technical publications. Manuscripts have been peer reviewed and edited. Documents published in this series can be cited in the scientific and technical literature. The Northwest Fisheries Science Center’s NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC series continues the NMFS- F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest and Alaska Fisheries Science Center, which subsequently was divided into the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The latter center uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC series. Reference throughout this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service. Reference this document as follows: Myers, J.M., J.J. Hard, E.J. Connor, R.A. Hayman, R.G. Kope, G. Lucchetti, A.R. Marshall, G.R. Pess, and B.E. Thompson. 2015. Identifying historical populations of steelhead within the Puget Sound distinct population segment. U.S. Dept. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS- NWFSC-128. doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-128. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-128 Identifying Historical Populations of Steelhead within the Puget Sound Distinct Population Segment doi:10.7289/V5/TM-NWFSC-128 James M. -

Inventory of Fish Species in the Bogachiel, Dosewallips, and Quinault River Basins, Olympic National Park, Washington

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Inventory of Fish Species in the Bogachiel, Dosewallips, and Quinault River Basins, Olympic National Park, Washington Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR—2015/955 ON THE COVER Top: (left) Federally threatened bull trout captured in Rustler Creek, North Fork Quinault River, Olympic National Park (OLYM) during fish inventory; (right) OLYM fisheries technicians conducting fish inventory via backpack electrofishing in Rustler Creek, North Fork Quinault River, OLYM. Middle: Upper Bogachiel River where OLYM fisheries crews inventoried 16 tributaries from June to August, 2002. Lower: (left) Sam Brenkman conducting snorkel survey in Dosewallips River, OLYM; (right) Rainbow trout captured in Big Creek, Quinault River, OLYM during fish inventory. Photo credits: Olympic National Park Files Inventory of Fish Species in the Bogachiel, Dosewallips, and Quinault River Basins, Olympic National Park, Washington Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR—2015/955 Samuel J. Brenkman1, Stephen C. Corbett1, Scott H. Sebring1 1National Park Service Olympic National Park 600 East Park Avenue Port Angeles, Washington 98362 April 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Washington Transportation Chronology

Transportation Chronology by Kit Oldham, updated 2004/p.1 Updated by Kit, 2004 WASHINGTON TRANSPORTATION CHRONOLOGY 1835. The Hudson's Bay Company ship Beaver is the first steamship to travel on Puget Sound. HL #1946 October-November, 1845 . The Michael Simmons-George Bush party cuts a makeshift road from Cowlitz Landing (now Toledo) on the Cowlitz River to Budd Inlet on Puget Sound, where they establish Tumwater, the first American settlement north of the Columbia River. Dorpat, 63; HL # 5646; Meeker, 158. 1851 . A crude wooden track portage line along the north bank of the Columbia river at the Cascades in the Columbia Gorge is the first railway constructed in the future Washington. Schwantes, Railroad , 15. 1852 . The first road established by law in the future Washington state is Byrd's Mill Road between Puyallup, Tacoma, and Steilacoom, established by the Oregon Territorial Legislature. Garrett, 3. 1853 . First overland passenger service from Olympia to the Columbia River begins; passengers are initially carried on freight wagons known as mudwagons (given the poor conditions on the route which do not improve much even when a military road is completed in 1861), with stage coaches coming into use as passengers numbers increase. (Except for the Columbia-Puget Sound connection, stagecoaches are little used in Western Washington, as the waters of Puget Sound provide the crucial transportation links). Dorpat, 66-67; Schwantes, Journey , 88-89. 1853. The steamer Fairy is the first steamer to provide regular service among Puget Sound ports. HL #869 January 7, 1853. Congress appropriates $20,000 for a military road from Fort Steilacoom to Fort Walla Walla by way of Naches Pass, a route that Indians used for generations to travel between Puget Sound and the Yakima Valley.