Resilient Podcast, Episode 26, February 2018.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Tumbling Dice and Other Tales from a Life Untitled Tammy Mckillip Mckillip University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2016-01-01 Tumbling Dice and Other Tales from a Life Untitled Tammy Mckillip Mckillip University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Mckillip, Tammy Mckillip, "Tumbling Dice and Other Tales from a Life Untitled" (2016). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 897. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/897 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TUMBLING DICE AND OTHER TALES FROM A LIFE UNTITLED TAMMY MCKILLIP Master’s Program in Creative Writing APPROVED: ______________________________________ Liz Scheid, MFA, Chair ______________________________________ Lex Williford, MFA ______________________________________ Maryse Jayasuriya, Ph.D. _________________________________________________ Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School TUMBLING DICE AND OTHER TALES FROM A LIFE UNTITLED ©Tammy McKillip, 2016 This work is dedicated to my beautiful, eternally-young mother, who taught me how to roll. Always in a hurry, I never stop to worry, Don't you see the time flashin’ by? …You’ve got to roll me And call me the tumbling dice —The Rolling Stones TUMBLING DICE AND OTHER TALES FROM A LIFE UNTITLED BY TAMMY -

Download Program

Tun fo e vi r yo IN rtua ur l aw ards Friday 7pm est on our facebook page @crudance competition convention live stream scholarships cash awards 3 competitive level entertainment winner choreographer winner and much more! CRU DANCE Saturday May 1st - Sunday May 2nd, 2021 ALBUQUERQUE, NM KIVA AUDITORIUM Saturday May 1st, 2021 Start Time: 9:00am Studio Check in- Studio A, F, P 8:30 AM Violet Bleger, Jolie Chowen, Sydney 1 P Waltz from Giselle Teen Pointe Small Group Intermediate DeLacey, Hannah Dobesh, Diana 9:00 AM Koshevoy, Sutton Schreiber, Anna Wiley 2 A Maniac Mini Acrobat Solo Intermediate Maria Moreno 9:03 AM Shaylah Apodaca, Zanae Cadena, Nadia Erives, Maria Gamez, Arianna Guzman, 3 F Grown Junior Jazz Small Group Novice 9:05 AM Jadelyne Maldonado, Alyson Ortiz, Nevaeh Ramos Gabriella Albert, Blythe Bleger, Maya Fontenot, Abigail Grindstaff, Rose Hamill, 4 P Don Quixote Ensemble Junior Ballet Large Group Novice 9:08 AM Gillian Reynolds, Eden Smith, Grace Tranum, Sophia Valdez, Naomi Verow 5 P Paquita Variation Senior Pointe Solo Elite Anna Wiley 9:12 AM 6 P Odalisque Variation Teen Pointe Solo Intermediate Hannah Dobesh 9:15 AM Alecia Baca, Bianca Gandara, Sonrisa Gonzales Atencio, Camilla Meraz, Ana 7 F Castle Teen Contemporary Large Group Novice 9:18 AM Oropeza, Carisse Padilla, Elicia Peralta, Jackie Pinon, Joslyn Purcella, Natalie Veleta Variation From Don 8 P Senior Pointe Solo Elite Sydney DeLacey 9:22 AM Quixote 9 P Perfect Senior Contemporary Solo Elite Anna Wiley 9:25 AM 10 P La Fille Mal Gardee Senior Pointe Duets/Trios -

The Riverdale Park

The Riverdale Park Town Crier September 2021 Volume 50, Issue 7 SPECIAL ELECTION NOTICE Ward 1 Special Election Page 1 Council Actions Page 2 AVISO DE ELECCIÓN ESPECIAL Fair Summaries Page 3 Ward 1 Special Election Page 3 In compliance with the terms of the Charter of the Mayor’s Report Page 4 Town Extensions Page 5 Town of Riverdale Park, Maryland, a Special Election will be held Stay-Up-To-Date Page 5 Virtual Meetings Page 6 Conforme a los Estatutos de la Ciudad de Riverdale Park, 2021 Dates Page 6 Mosquito Control Page 7 Maryland, se celebrará una elección el Neighborhood Services Page 8 Emergency Repair Grant Page 8 Saturday, September 11, 2021 Covid-19 Vaccine Page 9 Notices Page 9 - 10 To elect a Ward 1 Council Member Calendar Page 11 Important Numbers Page 12 Sábado, 11 de septiembre de 2021 Para elegir al Consejo del Distrito 1 Polls will be open from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. at Riverdale Fire Department, 4714 Queensbury Road Town of Riverdale Park Contact Information Las urnas abrirán de 7 a.m. a 8 p.m. en el Departamento de Bomberos de Riverdale, Town Hall 4714 Queensbury Road 5008 Queensbury Road 301-927-6381 CANDIDATES 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. CANDIDATOS Department of Public Works Council, Ward 1 5008 Queensbury Road Consejo, Distrito 1 301-927-6381 IFIOK INYANG 7:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Police Department RICHARD SMITH 5004 Queensbury Road 301-927-4343 Sarah Zolad, Chief Election Judge 24-hours Anne Kelly, Deputy Chief Election Judge Town of Riverdale Park Council Actions www.riverdaleparkmd.gov Cable Channels: 10 and 71 Legislative Meeting July 12, 2021 Mayor Consent Agenda Alan K. -

Microblogging As a Facilitator of Online Community in Graduate Education Vincent Anthony Rhodes Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Summer 2014 Microblogging as a Facilitator of Online Community in Graduate Education Vincent Anthony Rhodes Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Higher Education Commons, Online and Distance Education Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Rhodes, Vincent A.. "Microblogging as a Facilitator of Online Community in Graduate Education" (2014). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/zk4f-qn16 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICROBLOGGING AS A FACILITATOR OF ONLINE COMMUNITY IN GRADUATE EDUCATION by Vincent Anthony Rhodes B.S. May 1993, James Madison University M.A. May 2003, Old Dominion University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ENGLISH OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2014 Approved by: Rochelle Rodrigo (Member) UMI Number: 3581686 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

VA Beach World Finals Results

Virginia Beach, VA July 13-July 15, 2021 Elite 8 Petite Dancer Hannah Reese - Dimples - Dancensations Dance Center 1st Runner-Up - Addison Pasquariello - It Don't Mean A Thing - Dancensations Dance Center 2nd Runner-Up - Gabrielle Joyner - Work Me Down - Expose Performing Arts Elite 8 Junior Dancer Caroline Garcia - Big Time - Dancensations Dance Center 1st Runner-Up - Ella Fthenos - Higher - Dancensations Dance Center 2nd Runner-Up - Savanna Moore - Show Off - Dancensations Dance Center Elite 8 Teen Dancer Giovanna Hart - Dangerous - Dancensations Dance Center 1st Runner-Up - Faraona Bonilla - Kimbara - Expose Performing Arts 2nd Runner-Up - Alyssa Gomon - Call Me Back - Mia Bella Academy Of Dance Elite 8 Senior Dancer Priscilla Camino - Roll In The Hay - Dancensations Dance Center 1st Runner-Up - Janiyah Taylor - Black & Gold - Expose Performing Arts 2nd Runner-Up - Naomi Buckle - Master Piece - Expose Performing Arts Top Select Junior Solo 6 - Kylee Silva - Tiny Voice - Dynamic Movements 7 - Addison Holmes - I'm A Brass Band - Dancensations Dance Center 8 - Despina Eftychiou - Rhythm Of The Night - Dancensations Dance Center 9 - Kinley Pivac - Daybreak - Dynamic Movements 10 - Kaylee Maceda - Strongest Suit - Dancensations Dance Center Top Select Teen Solo 6 - Kiera McAllister - Always True To You In My Fashion - Dancensations Dance Center 7 - Addison Joy Adams - Beautiful - Dancensations Dance Center 8 - Nylah Pelzer - Bitter Earth - Dynamic Movements 9 - Alyssa Gomon - Believe - Mia Bella Academy Of Dance 10 - Sienna Moore - Without -

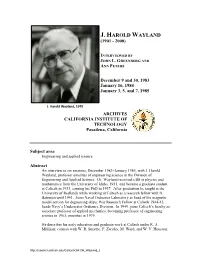

Interview with J. Harold Wayland

J. HAROLD WAYLAND (1901 - 2000) INTERVIEWED BY JOHN L. GREENBERG AND ANN PETERS December 9 and 30, 1983 January 16, 1984 January 3, 5, and 7, 1985 J. Harold Wayland, 1979 ARCHIVES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California Subject area Engineering and applied science Abstract An interview in six sessions, December 1983–January 1985, with J. Harold Wayland, professor emeritus of engineering science in the Division of Engineering and Applied Science. Dr. Wayland received a BS in physics and mathematics from the University of Idaho, 1931, and became a graduate student at Caltech in 1933, earning his PhD in 1937. After graduation he taught at the University of Redlands while working at Caltech as a research fellow with H. Bateman until 1941. Joins Naval Ordnance Laboratory as head of the magnetic model section for degaussing ships; War Research Fellow at Caltech 1944-45; heads Navy’s Underwater Ordnance Division. In 1949, joins Caltech’s faculty as associate professor of applied mechanics, becoming professor of engineering science in 1963; emeritus in 1979. He describes his early education and graduate work at Caltech under R. A. Millikan; courses with W. R. Smythe, F. Zwicky, M. Ward, and W. V. Houston; http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechOH:OH_Wayland_J teaching mathematics; research with O. Beeck. Fellowship, Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen; work with G. Placzek and M. Knisely; interest in rheology. On return, teaches physics at the University of Redlands meanwhile working with Bateman. Recalls his work at the Naval Ordnance Laboratory and torpedo development for the Navy. Discusses streaming birefringence; microcirculation and its application to various fields; Japan’s contribution; evolution of Caltech’s engineering division and the Institute as a whole; his invention of the precision animal table and intravital microscope. -

West Coast Rock Final Version

WEST COAST ROCK AND THE COUNTERCULTURE MOVEMENT Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Christina DREIER am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr.phil. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2012 An dieser Stelle möchte ich mich bei meinem Betreuer Prof. Dr. Hugo Keiper für seine Unterstützung auf meinem Weg von der Idee bis zur Fertigstellung der Arbeit herzlich bedanken. Seine Ideen, Anregungen und Hinweise, sowie sein umfangreiches musikalisches, kulturelles und literarisches Wissen waren mir eine große Hilfe. Des Weiteren gilt mein Dank meinem Onkel Patrick, der die Arbeit Korrektur gelesen und mir dadurch sehr geholfen hat. Natürlich möchte ich mich auch von ganzem Herzen bei all jenen bedanken, die mich während meiner gesamten Studienzeit tatkräftig unterstützt haben. Danke Mama, Papa, Oma, Opa, Lisa, Eva, Markus, Gabi, Erwin UND DANKE JÜRGEN! . Table of Contents 0. Timeline ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Socio-Historical Background ....................................................................................................................... 4 2.1. Political Issues ............................................................................................................................... -

SM-July-August-September-2019.Pdf

Suspense, Mystery, Horror and Thriller Fiction FALL 2019 Beware: The Frightening Fall CHRIS BAUER KAREN KATCHUR ADRIAN McKINTY LESLIE MEIER KARIN SLAUGHTER DAVID BALDACCI IRIS JOHANSEN DOUGLAS PRESTON & On Writing LINCOLN CHILD DARYL WOOD GERBER & Meet Debut Authors Enough! EVE CALDER DENNIS PALUMBO DEBORAH GOODRICH ROYCE Don’t miss this new from bestselling author Talia Inger is a rookie CIA case offi cer assigned not to the Moscow desk as she had hoped but to the forgotten backwaters of Eastern Europe—a department only known as “Other.” When she is tasked with helping a young, charming Moldovan executive secure his designs for a revolutionary defense technology, she fi gures she’ll be back in DC within a few days. But that’s before she knows where the designs are stored—and who’s after them. With her shady civilian partner, Adam Tyler, Talia takes a deep dive into a world where criminal minds and unlikely strategies compete for access to the Gryphon, a high-altitude data vault that hovers in the mesosphere. But is Tyler actually helping her? Or is he using her for his own dark purposes? | To learn more, visit JamesRHannibal.com | pm Available Wherever Books and eBooks Are Sold From the Editor We write this letter with a very heavy heart. Author Mark Sadler, a Suspense CREDITS John Raab Magazine family member, suddenly President & Chairman passed away on August 24, 2019. Mark Shannon Raab was the author of “Blood on His Hands” Creative Director and “Kettle of Vultures.” Romaine Reeves We all go through our days hoping to CFO meet people who have a positive impact on our lives. -

2020 Top 110 POP Songs Karaoke the Top 110+ POP/Rock/R&B Songs of 2020

2/6/2021 2020 Top 110 POP Songs Karaoke The Top 110+ POP/Rock/R&B Songs of 2020. DOWNLOAD includes MP3G Karaoke songs in a .zip folder. MP3+G album downloads to be used with Karaoke Computer Software. See list of songs below for ALL songs included in package. An excel spreadsheet of all songs is included. ARTIST SONG TITLE Aguilera, Christina Reflection (Mulan Soundtrack) Archuleta, David From a Distance Ava Max Salt Ava Max Kings & Queens Ava Max Who's Laughing Ballerini, Kelsea The Other Girl (duet Halsey) Bareilles, Sara Orpheus Bareilles, Sara More Love Beer, Madison Selfish Beyonce Black Parade Bieber, Justin Yummy Blacc, Aloe My Way Black Pumas Colors Bon Jovi Unbroken Carlile, Brandi Carried Me With You Clarkson, Kelly I Dare You Clemmons, Riley Fighting For Me Coldplay Orphans Cyrus, Miley Midnight Sky https://www.buykaraokedownloads.com/2020-top-110-pop-songs.html 2/7 2/6/2021 2020 Top 110 POP Songs Karaoke Cyrus, Noah July Derulo, Jason Take You Dancing Dion, Celine Say Yes Disturbed Hold On To Your Memories Disturbed Inside The Fire Eilish, Billie Bad Guy Eilish, Billie My Future Eurovision, The Story of Fire Husavik Saga Eurovision, The Story of Fire Jaja Ding Dong Saga Evanesence Wasted On You Evans, Luke Love Is A Battlefield Gomez, Selena Feel Me Goulding, Ellie Power Grande, Ariana 34+35 Gregory, Tom Fingertips Halestorm Break In (ft. Amy Lee) Halsey You Should Be Sad Halsey Be Kind HER Wrong Places HER Focus HER Hard Place https://www.buykaraokedownloads.com/2020-top-110-pop-songs.html 3/7 2/6/2021 2020 Top 110 POP Songs Karaoke HER Comfortable HER Hold On Hillsong Worship King of Kings Horan, Niall Black and White Imagine Dragons Birds Jonas Brothers Only Human Jonas Brothers What A Man Gotta Do Keys, Alicia Underdog Lady Gaga Alice Lady Gaga Stupid Love Lady Gaga Rain On Me (ft. -

Introducing Theresa Sokyrka

Tongue n Groove 518 5th Street South, Lethbridge AB Sunday, Sept. 4 Doors at 8:00 p.m. Show at 8:30 p.m. Advance tickets $20 Door tickets $30 Theresa Sokyrka Online T Ώ website: TheresaSokyrka.ca Ώ Twitter: theresa_sokyrka Ώ Facebook: theresasokyrka Ώ Sonic Bids: theresasokyrka Ώ Myspace: theresasokyrka Tickets available at Blueprint Entertainment 519 4th Ave South 2 Theresa Sokyrka The musical talent of Canadian singer/songwriter, Theresa Sokyrka is coming to Lethbridge. If you like smooth, inoffensive songs sung with a smoky tone, you’ll adore Theresa. If you don’t mind listening to music where you can “feel” the music, you will respect her personal style. Theresa Sokyrka’s smoky vocal tone evokes emotion and soul. Music has been a large part of Theresa’s life. She began her musical career at the age of nine when she started violin lessons. You can’t pigeon-hole Theresa’s music — she sings folk, rock, jazz and pop, goes beyond playing the violin and is now busy singing, song writing and performing for Canadian audiences. She was one of the featured performers in Toronto on August 6th 2011 for the Trek4MS Benefit Concert. Among her albums are These Old Charms (gold and Juno-nominated) and Something Is Expected (adult alternative album of original music) that contains two tracks (“Waiting Song” and “Sandy Eyes”) with subsequent videos that played on the Much Music network. Four Hours in November Five original songs written and ar- ranged by Theresa and recorded in November 2004: Change the World, Diamond Joe, I Believe in You, Turned My Back and She Let Her Hair Down. -

12/1 Transcript

29068 1 2 3 4 5 6 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * 7 MEETING OF THE SUPREME COURT ADVISORY COMMITTEE 8 December 1, 2017 9 (FRIDAY SESSION) 10 11 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Taken before D'Lois L. Jones, Certified 20 Shorthand Reporter in and for the State of Texas, reported 21 by machine shorthand method, on the 1st day of December, 22 2017, between the hours of 9:07 a.m. and 4:50 p.m., at the 23 Texas Association of Broadcasters, 502 East 11th Street, 24 Suite 200, Austin, Texas 78701. 25 D'Lois Jones, CSR 29069 1 INDEX OF VOTES 2 Votes taken by the Supreme Court Advisory Committee during 3 this session are reflected on the following pages: 4 Vote on Page 5 Lawyer access to jurors' social media 29,272 6 Lawyer access to 7 jurors' social media 29,273 8 Lawyer access to jurors' social media 29,274 9 10 11 12 13 Documents referenced in this session 14 17-29 Rule 308b Final Draft with Orsinger Email, 11-29-17 15 17-30 TAJC Supplemental Report & Exhibits 16 17-31 Revised Proposed Court Staff Policy on Patrons Assistance, 11-27-17 17 17-32 Revised Proposed Clerk Policy on Court Patron 18 Assistance, 11-27-17 19 17-33 Proposed Changes to Disciplinary Rules, Access to Juror Social Media, 11-28-17 20 17-34 Summary of Changes to Protective Order Kit, 11-21-17 21 17-35 Protective Order Kit Final Draft, 11-21-17 22 (highlighted) 23 17-36 Protective Order Kit Final Draft, 11-21-17 24 25 D'Lois Jones, CSR 29070 1 *-*-*-*-* 2 CHAIRMAN BABCOCK: All right, welcome, 3 everybody.