How to Create Bass Lines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GENERAL MUSIC Grade 3

GENERAL MUSIC Grade 3 Course Overview: Grade 3 students will engage in a wide variety of music activities, including singing, playing instruments, and dancing. Music notation is addressed through reading rhythm subdivisions to sixteenth notes, multiple beat notations, and reading five note melodic notations on a five line staff. They also continue building the foundation of musical vocabulary. NOTE: Throughout this document, learning target types are identified as knowledge (“K”), reasoning (“R”), skill (“S”), or product (“P”). NATIONAL STANDARD 1: Students sing, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music. Benchmark 1: Students sing independently, on pitch and in rhythm, with appropriate timbre, diction, and posture, and maintain a steady tempo. Learning Targets (Type): 1) I can label a melody that moves by step, skip, or repeat when I listen to a so n g or sing a song. (R) 2) I can identify steps, skips, and repeats when I see them on a treble staff. (K) 3) I can play the steady beat with body percussion or on an instrument when I sing a song. (S) 4) I can play the melodic rhythm of the song using body percussion or unpitched percussion instruments. (S) Benchmark 2: Students sing expressively, with appropriate dynamics, phrasing, and interpretation. Learning Targets (Type): 1) I can make and perform a dynamic plan for a song using p, mp, mf, and f. (S) 2) I can count the number of phrases in a song. (K) Benchmark 3: Students sing from memory a varied repertoire of songs representing genres and styles from diverse cultures. Learning Targets (Type): 1) I can sing holiday music from around the world in December. -

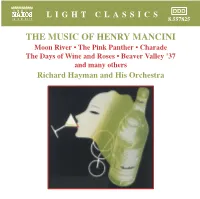

THE MUSIC of HENRY MANCINI the Boston Pops Orchestra During Arthur Fiedler’S Tenure, Providing Special Arrangements for Dozens of Their Hit Albums and Famous Singles

557825 bk ManciniUS 2/11/05 09:48 Page 4 Richard Hayman LIGHT CLASSICS DDD One of America’s favourite “Pops” conductors, Richard Hayman was Principal “Pops” conductor of the Saint 8.557825 Louis, Hartford and Grand Rapids symphony orchestras, of Orchestra London Canada and the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, and also held the post with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra for many years. His original compositions are standards in the repertoire of these ensembles as well as frequently performed selections by many orchestras and bands throughout the world. For over thirty years, Richard Hayman served as the chief arranger for THE MUSIC OF HENRY MANCINI the Boston Pops Orchestra during Arthur Fiedler’s tenure, providing special arrangements for dozens of their hit albums and famous singles. Under John Williams’ direction, the orchestra continues to programme his award- winning arrangements and orchestrations. Though more involved with the symphony orchestra circuit, Richard Moon River • The Pink Panther • Charade Hayman served as musical director and/or master of ceremonies for the tour shows of many popular entertainers: Kenny Rogers, Johnny Cash, Olivia Newton-John, Tom Jones, Englebert Humperdinck, The Carpenters, The The Days of Wine and Roses • Beaver Valley ’37 Osmonds, Al Hirt, Andy Williams and many others. Richard Hayman and His Orchestra recorded 23 albums and 27 hit singles for Mercury Records, for which he and many others served as musical director for twelve years. Dozens of his original compositions have been recorded by various artists all over the world. He has also arranged and conducted recordings for more than 50 stars of the motion Richard Hayman and His Orchestra picture, stage, radio and television worlds, and has also scored Broadway shows and numerous motion pictures. -

John Corigliano's Fantasia on an Ostinato, Miguel Del Aguila's Conga for Piano, and William Bolcom's Nine New Bagatelles

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2016 Pedagogical and Performance Aspects of Three American Compositions for Solo Piano: John Corigliano's Fantasia on an Ostinato, Miguel del Aguila's Conga for Piano, and William Bolcom's Nine New Bagatelles Tse Wei Chai Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Chai, Tse Wei, "Pedagogical and Performance Aspects of Three American Compositions for Solo Piano: John Corigliano's Fantasia on an Ostinato, Miguel del Aguila's Conga for Piano, and William Bolcom's Nine New Bagatelles" (2016). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5331. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5331 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pedagogical and Performance Aspects of Three American Compositions for Solo Piano: John Corigliano’s Fantasia on an Ostinato, Miguel del Aguila’s Conga for Piano, and William Bolcom’s Nine New Bagatelles Tse Wei Chai A Doctoral Research Project submitted to The College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance James Miltenberger, D.M.A., Committee Chair & Research Advisor Peter Amstutz, D.M.A. -

Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!E Following Article first Appeared in the Dutch Magazine “De Fagot”

THE DOUBLE REED 103 Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!e following article first appeared in the Dutch magazine “De Fagot”. It is reprinted here with permission in an English translation by James Aylward. Ed.) t used to be that orchestras, when they appointed a new second bassoon, would not take the best player, but a lesser one on instruction from the !rst bassoonist: the prima donna. "e !rst bassoonist would then blame the second for everything that went wrong. It was also not uncommon that the !rst bassoonist, when Ihe made a mistake, to shake an accusatory !nger at his colleague in clear view of the conductor. Nowadays it is clear that the second bassoon is not someone who is not good enough to play !rst, but a specialist in his own right. Jos de Lange and Ronald Karten, respectively second and !rst bassoonist from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra explain.) BASS VOICE Jos de Lange: What makes the second bassoon more interesting over the other woodwinds is that the bassoon is the bass. In the orchestra there are usually four voices: soprano, alto, tenor and bass. All the high winds are either soprano or alto, almost never tenor. !e "rst bassoon is o#en the tenor or the alto, and the second is the bass. !e bassoons are the tenor and bass of the woodwinds. !e second bassoon is the only bass and performs an important and rewarding function. One of the tasks of the second bassoon is to control the pitch, in other words to decide how high a chord is to be played. -

Music from Peter Gunn

“The Music from ‘Peter Gunn’”--Henry Mancini (1958) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Mark A. Robinson (guest post)* Henry Mancini Henry Mancini (1924-1994) was the celebrated composer of a parade of song standards, particularly remembered for his work in television and film composition. Among his sparkling array of memorable melodies are the music for “The Pink Panther” films, the “Love Theme from ‘Romeo and Juliet’,” and his two Academy Award-winning collaborations with lyricist Johnny Mercer, “Moon River” for the 1961 film “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” and the title song for the 1962 feature “Days of Wine and Roses.” Born Enrico Nicola Mancini in the Little Italy neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio, Henry Mancini was raised in West Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. Though his father wished his son to become a teacher, Mancini was inspired by the music of Hollywood, particularly that of the 1935 Cecil B. DeMille film “The Crusades.” This fascination saw him embark on a lifelong journey into composition. His first instrument of choice was the piccolo, but soon he drifted toward the piano, studying under Pittsburgh concert pianist and Stanley Theatre conductor Max Adkins. Upon graduating high school, Mancini matriculated at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, but quickly transferred to the Julliard School of Music, concentrating his studies in piano, orchestration, and composition. When America entered World War II, Mancini enlisted in the United States Army in 1943. Assigned to the 28th Air Force Band, he made many connections in the music industry that would serve him well in the post-war years. -

The Meshuggah Quartet

The Meshuggah Quartet Applying Meshuggah's composition techniques to a quartet. Charley Rose jazz saxophone, MA Conservatorium van Amsterdam, 2013 Advisor: Derek Johnson Research coordinator: Walter van de Leur NON-PLAGIARISM STATEMENT I declare 1. that I understand that plagiarism refers to representing somebody else’s words or ideas as one’s own; 2. that apart from properly referenced quotations, the enclosed text and transcriptions are fully my own work and contain no plagiarism; 3. that I have used no other sources or resources than those clearly referenced in my text; 4. that I have not submitted my text previously for any other degree or course. Name: Rose Charley Place: Amsterdam Date: 25/02/2013 Signature: Acknowledgment I would like to thank Derek Johnson for his enriching lessons and all the incredibly precise material he provided to help this project forward. I would like to thank Matis Cudars, Pat Cleaver and Andris Buikis for their talent, their patience and enthusiasm throughout the elaboration of the quartet. Of course I would like to thank the family and particularly my mother and the group of the “Four” for their support. And last but not least, Iwould like to thank Walter van de Leur and the Conservatorium van Amsterdam for accepting this project as a master research and Open Office, open source productivity software suite available on line at http://www.openoffice.org/, with which has been conceived this research. Introduction . 1 1 Objectives and methodology . .2 2 Analysis of the transcriptions . .3 2.1 Complete analysis of Stengah . .3 2.1.1 Riffs . -

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018 Rebellion, genre, drugs, freedom, unity, sex, technology, place, community …………………. Disco • Disco marked the dawn of dance-based popular music. • Growing out of the increasingly groove-oriented sound of early '70s and funk, disco emphasized the beat above anything else, even the singer and the song. • Disco was named after discotheques, clubs that played nothing but music for dancing. • Most of the discotheques were gay clubs in New York • The seventies witnessed the flowering of gay clubbing, especially in New York. For the gay community in this decade, clubbing became 'a religion, a release, a way of life'. The camp, glam impulses behind the upsurge in gay clubbing influenced the image of disco in the mid-Seventies so much that it was often perceived as the preserve of three constituencies - blacks, gays and working-class women - all of whom were even less well represented in the upper echelons of rock criticism than they were in society at large. • Before the word disco existed, the phrase discotheque records was used to denote music played in New York private rent or after hours parties like the Loft and Better Days. The records played there were a mixture of funk, soul and European imports. These "proto disco" records are the same kind of records that were played by Kool Herc on the early hip hop scene. - STARS and CLUBS • Larry Levan was the first DJ-star and stands at the crossroads of disco, house and garage. He was the legendary DJ who for more than 10 years held court at the New York night club Paradise Garage. -

Small Episodes, Big Detectives

Small Episodes, Big Detectives A genealogy of Detective Fiction and its Relation to Serialization MA Thesis Written by Bernardo Palau Cabrera Student Number: 11394145 Supervised by Toni Pape Ph.D. Second reader Mark Stewart Ph.D. MA in Media Studies - Television and Cross-Media Culture Graduate School of Humanities June 29th, 2018 Acknowledgments As I have learned from writing this research, every good detective has a sidekick that helps him throughout the investigation and plays an important role in the case solving process, sometimes without even knowing how important his or her contributions are for the final result. In my case, I had two sidekicks without whom this project would have never seen the light of day. Therefore, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Toni Pape, whose feedback and kind advice was of great help. Thank you for helping me focus on the important and being challenging and supportive at the same time. I would also like to thank my wife, Daniela Salas, who has contributed with her useful insight, continuous encouragement and infinite patience, not only in the last months but in the whole master’s program. “Small Episodes, Big Detectives” 2 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 1. Literature Seriality in the Victorian era .................................................................... 8 1.1. The Pickwick revolution ................................................................................... 8 -

Laker Drumline Marching Bass Drum Technique

Laker Drumline Marching Bass Drum Technique This packet is intended to define a base framework of knowledge to adequately play a marching bass drum at the collegiate level. We understand that every high school drumline has its own approach to technique, so it’s crucial that ALL prospective members approach their hands with a fresh mind and a clean slate. Mastery of the following concepts & terminology will dramatically improve your experience during the audition process and beyond. Happy drumming! APPROACH The technique outlined in this packet is designed to maximize efficiency of motion and sound quality. It is necessary to use a high velocity stroke while keeping your grip and your muscles relaxed. Keep these key points in mind as you work to refine the music in this packet. Tension in your upper body, lack of oxygen to your muscles, and squeezing the stick are good examples of technique errors that will hinder your ability to achieve the sound quality, efficiency, and control that we strive for. GRIP Fulcrum Place the mallet perpendicularly across the second segment of your index finger. Place your thumb on the mallet so that the thumbnail is directly across from your index finger. ** This is the essential point of contact between your hands and the stick. It should be thought of as the primary pressure point in your fingers and pivot point on the stick. The entire pad of your thumb should remain in contact with the mallet at all times. As a bass drummer, about 60% of the pressure in your hands should lie in the fulcrum. -

10 - Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1

Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef Chapter 2. Bass Clef In this chapter you will: 1.Write bass clefs 2. Write some low notes 3. Match low notes on the keyboard with notes on the staff 4. Write eighth notes 5. Identify notes on ledger lines 6. Identify sharps and flats on the keyboard 7.Write sharps and flats on the staff 8. Write enharmonic equivalents date: 2.1 Write bass clefs • The symbol at the beginning of the above staff, , is an F or bass clef. • The F or bass clef says that the fourth line of the staff is the F below the piano’s middle C. This clef is used to write low notes. DRAW five bass clefs. After each clef, which itself includes two dots, put another dot on the F line. © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 10 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef 2.2 Write some low notes •The notes on the spaces of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom space are: A, C, E and G as in All Cows Eat Grass. •The notes on the lines of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom line are: G, B, D, F and A as in Good Boys Do Fine Always. 1. IDENTIFY the notes in the song “This Old Man.” PLAY it. 2. WRITE the notes and bass clefs for the song, “Go Tell Aunt Rhodie” Q = quarter note H = half note W = whole note © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 11 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. -

The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1966 The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions J. Wayne Johnson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, J. Wayne, "The Identification of Basic Problems Found in the Bassoon Parts of a Selected Group of Band Compositions" (1966). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2804. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2804 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IDENTIFICATION OF BAS~C PROBLEMS FOUND IN THE BASSOON PARTS OF A SELECTED GROUP OF BAND COMPOSITI ONS by J. Wayne Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the r equ irements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Music Education UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan , Ut a h 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE BASSOON 3 THE I NSTRUMENT 20 Testing the bassoon 20 Removing moisture 22 Oiling 23 Suspending the bassoon 24 The reed 24 Adjusting the reed 25 Testing the r eed 28 Care of the reed 29 TONAL PROBLEMS FOUND IN BAND MUSIC 31 Range and embouchure ad j ustment 31 Embouchure · 35 Intonation 37 Breath control 38 Tonguing 40 KEY SIGNATURES AND RELATED FINGERINGS 43 INTERPRETIVE ASPECTS 50 Terms and symbols Rhythm patterns SUMMARY 55 LITERATURE CITED 56 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands.