The Impact of Early Learning Design on the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Curriculum Design Processes and Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Participant Directory

Participant Directory Dr James Aird Durham University [email protected] Prof David Alexander Durham University [email protected] Dr Almudena Alonso-Herrero Instituto de Fisica de Cantabria [email protected] Miss Adlyka Annuar Durham University [email protected] Ms Mojegan Azadi UC San Diego [email protected] Prof Amy Barger University of Wisconsin [email protected] Prof Peter Barthel Kapteyn Institute, Groningen [email protected] Dr Franz Bauer Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile [email protected] Mr Emmanuel Bernhard University of Sheffield [email protected] Miss Patricia Bessiere University of Sheffield [email protected] Prof Andrew Blain University of Leicester [email protected] Mr Marvin Blank University of Kiel [email protected] Dr Frederic Bournaud CEA Saclay [email protected] Prof Richard Bower Durham University [email protected] Mr Christopher Carroll Dartmouth College [email protected] Miss Claire Cashmore University of Leicester [email protected] Mr Chien-Ting Chen Dartmouth College [email protected] Dr Ana Chies Santos University of Nottingham [email protected] Dr Laure Ciesla University of Crete [email protected] Dr Luis Colina CSIC [email protected] Prof Francoise Combes Observatoire de Paris [email protected] Dr Scott Croom University of Sydney [email protected] Dr Richard Davies MPE [email protected] Dr Colin DeGraf Hebrew University of Jerusalem [email protected] Dr -

University of Leicester International Study Centre

International Foundation Year 2014/15 You have just made your first important discovery... University of Leicester International Study Centre Top 20 UK university www.le.ac.uk/isc in all major 2014 university league tables 3 Degree preparation at the University of Leicester Welcome The International Foundation Year The International Foundation Year An excellent record Programme offers a pathway to Programme is taught at the University for progression to Leicester undergraduate study for international of Leicester International Study Centre, students who have completed high school, a specialist facility for degree preparation but who may not meet the requirements where students are taught in small classes of University Contents The University of Leicester is consistently highly for direct entry to the University. Combining which simulate the style of teaching they 94% of Leicester academic modules, study skills and will experience at undergraduate level. ranked: 14th by The Times 2014 and 13th by International Study Centre Inspirational Teaching English language training, this programme and Research 6-7 The Guardian 2014. Leicester is also ranked in the prepares students to meet the challenges students who completed the of degree-level study at the University. Your Career 8-11 top 2% of universities in the world by the QS World International Foundation University Rankings 2013 and THE World University Your Campus 12-19 Year programme were Rankings 2013. Your City 20-23 offered a place on a degree For several years, the University of Leicester has recorded some of the The International Study Centre 24-26 at the University in 2013. highest scores for student satisfaction in the National Student Survey, International Foundation Year 27 consistently featuring amongst the top 20 universities in England. -

Leicester Student Voice Report

Leicester Student Voice Executive report February 2020 Foreword This report sets out the findings of a ‘Leicester Student Voice’ event organised jointly by Leicester City Council, De Montfort University and the University of Leicester. The research forms part of a three-year partnership project aimed at increasing the proportion of local graduates who stay in Leicester to begin their career. In 2017, an average of 28% of graduates from Leicester’s two city universities stayed to live and work locally, compared to a national average of 48.4%. Retaining graduate talent is critical for the success of city economies like Leicester as the UK continues to specialise in ever more high-skilled, knowledge intensive activities. The Leicester Graduate Retention partnership will identify and implement actions aimed at influencing students to stay in Leicester and progress on to high-skilled career pathways with locally-based businesses, including support for start-up activity. 2 The Project actions will be determined based on hearing the student and business voice throughout the project, as critical stakeholders for developing meaningful change. The project team wishes to thank the students who willingly offered their time, experiences and ideas at the Leicester Student Voice event. Adele Browne Rob Fryer Sally Hackett Peter Chandler Jo Ives Adele Browne De Montfort University ‘One thing in Leicester is inclusion: No matter who you are - race, gender, sexuality - you can find your place here; you are accepted 98% of the time… Leicester I think has one of the most vibrant cultures I’ve been to and it’s a place where you can be yourself.’ Event participant 1. -

Pathways Assistant (Fixed Term Until September 2022) REQ210720

Marketing & Advancement Pathways Assistant (Fixed term until September 2022) REQ210720 As part of the University’s ongoing commitment to redeployment, please note that this vacancy may be withdrawn at any stage of the recruitment process if a suitable redeployee is identified. Job Description Job Grade: Administrative Services Grade 4 Job Purpose Pathways is one of 29 national partnerships working to deliver the Office for Students (OFS) current widening participation scheme – Uni Connect. Working as a key member of the Pathways partnership (which is comprised of Loughborough University, University of Leicester, De Montfort University, Loughborough College and Leicester College) this role is to effectively signpost to outreach information and opportunities across the county and deliver a range of bespoke outreach events and initiatives to raise awareness of routes into and opportunities offered by Higher Education. As well as working with colleagues across Marketing and Advancement, the post-holder will work within a team of Pathways Assistants who will be based at University of Leicester and DMU as well as with Pathways colleagues based within our partner FE Colleges. They will undertake two key roles. One will be to support a caseload of target schools based across Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland to access information and opportunities for their students around progression in education. The other will be to support the Pathways Project Officer and Strategic Outreach Officer in the design and development of a programme of events, usually taking place outside of school or college, during the holiday periods. Day to day responsibilities will include maintaining effective communication between colleagues in the pathways team and staff in schools, providing support to develop new initiatives in response to evidence of need provided by schools, colleges and third sector partners (such a local authorities and charities) and delivering workshops and informational sessions to students in both formal education and community settings. -

Early Career Profiles of STFC Phd Students

Early career profiles of STFC PhD students April 2010 Early Career profiles of STFC PhD students April 2010 Early Career profiles of STFC PhD students April 2010 Acknowledgements STFC would like to thank all former students who responded to the request for information about their careers and appreciate the time and effort which made the publication of these profiles possible. The material for the career profiles was collected by DTZ. Science and Technology Facilities Council Polaris House, North Star Avenue, Swindon SN2 1SZ, UK T: +44 (0)1793 442000 F: +44 (0)1793 442002 E: [email protected] www.stfc.ac.uk Early Career profiles of STFC PhD students April 2010 Contents Introduction 1 Destinations of former STFC students 1 Career profiles 2 Private Sector Project Manager / Senior Software Engineer, Tessella 2 Software and Digital Engineer, Tandberg 3 Government and public sector Investment Policy and Analysis Manager, Office of the Rail Regulator 4 Universities and Research Establishments Marie Curie Fellow, University Of Birmingham 5 Data Centre Scientist, University of Leicester 6 Post Doctoral Scholar, Las Cumbres Observatory, USA 7 Post-doctoral Researcher, Max Planck Institut für Astronomie 8 Reader, Department of Physics, Durham University 9 Early Career profiles of STFC PhD students April 2010 Introduction Destinations of former STFC In 2009, the Science and Technology Facilities students Council (STFC) commissioned DTZ to find out The 2009 survey, indicated that 46% of the about the career paths that former PhD former students who responded were working students have followed and how they have in universities, 27% in the private sector and made use of the skills they developed during 23% in other government or public sector their study. -

Enterprising Universities Using the Research Base to Add Value to Business

Policy Report September 2010 Enterprising Universities Using the research base to add value to business 1100901_EnterprisingUniversities.indd00901_EnterprisingUniversities.indd A 009/09/20109/09/2010 115:025:02 The 1994 Group > The 1994 Group is established to promote excellence in university research and teaching. It represents 19 of the UK’s leading research-intensive, student focused universities. Around half of the top 20 universities in UK national league tables are members of the group. > Each member institution delivers an extremely high standard of education, demonstrating excellence in research, teaching and academic support, and provides learning in a research-rich community. > The 1994 Group counts amongst its members 12 of the top 20 universities in the Guardian University Guide 2011 league tables published on the 8th June 2010. 7 of the top 10 universities for student experience are 1994 Group Universities (2009 National Student Survey). In 17 major subject areas 1994 Group universities are the UK leaders achieving 1st place in their fi eld (THE RAE subject rankings 2008). 57% of the 1994 Group's research is rated 4* 'world- leading' or 3* 'internationally excellent' (RAE 2008, HEFCE). > The 1994 Group represents: University of Bath, Birkbeck University of London, Durham University, University of East Anglia, University of Essex, University of Exeter, Goldsmiths University of London, Institute of Education University of London, Royal Holloway University of London, Lancaster University, University of Leicester, Loughborough -

Dr Dimitrios Varvarigos Curriculum Vitae (March 2021)

Dr Dimitrios Varvarigos Curriculum Vitae (March 2021) Contact Details University of Leicester, School of Business – Department of Economics, Finance & Accounting, Office 2.05, Mallard House (Brookfield campus), 266 London Road, Leicester LE2 1RQ, United Kingdom [email protected] https://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/business/people/academic/dvarvarigos +44 (0) 116 252 2184 Education 2002‐2005 PhD Economics, University of Manchester (UK) 2001‐2002 MSc Economics (with distinction), University of Manchester (UK) 1996‐2000 BSc (πτυχίο in Greek) Economics, University of Piraeus (Greece) Other Qualifications Fellow of the Higher Education Academy Employment History 08/2016‐currently Associate Professor, School of Business, University of Leicester 04/2011‐07/2016 Senior Lecturer, Department of Economics, University of Leicester 01/2008‐03/2011 Lecturer, Department of Economics, University of Leicester 09/2006‐12/2007 Lecturer, Department of Economics, Loughborough University 09/2005‐08/2006 Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Economic Studies, University of Manchester Research Interests Growth theory. Cultural and social aspects in economic development. Corruption, tax evasion, and economic activity. Demographic change. Publications 1. Varvarigos, D. (2021). “Upstream intergenerational transfers in economic development: The role of family ties and their cultural transmission,” Journal of Mathematical Economics (forthcoming). 2. Varvarigos, D. (2020). “Cultural transmission, education‐promoting attitudes, and economic development,” Review of Economic Dynamics, 37, 173‐194. 3. Ohinata, A., and Varvarigos, D. (2020). “Demographic transition and fertility rebound in economic development,” Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 122, 1640‐1670. 4. Varvarigos, D., and Xin, G. (2020). “Social distance and economic development,” Macroeconomic Dynamics, 24, 860‐881. 5. Kontogiannis, N., Litina, A., and Varvarigos, D. -

Progression Routes

Progression Routes The partnership has designed some ideal progression routes for schools to take, if they so wish, in order to maximise the opportunities of the young people taking part. These are not the only progression routes available and are not set to be followed but are simply given to identify potential ideas which could be used as a template for building the individual schools suite of activities. 1 Group Provider Activity Name Year 7 De Montfort University Problem Solving Year 8 University of Leicester Masterclasses Year 9 Loughborough University Experience HE Day Year 10 De Montfort University Campus Life Year 11 University of Leicester Goal Setting Key Target Groups REACH Preparing for HE, for students with Autism and Asperger’s 2 Group Provider Activity Name Year 7 De Montfort University Problem Solving Year 8 University of Leicester UE Day Year 9 De Montfort University Visual CV Year 10 Loughborough University Challenge Day Year 11 University of Leicester Goal Setting Key Target Groups REACH Study skills - Dyslexia or Specific Learning Differences 3 Group Provider Activity Name Year 7 De Montfort University Problem Solving Year 8 University of Leicester Masterclasses Year 9 Loughborough University Experience HE Day Year 10 University of Leicester Goal Setting Year 11 Loughborough University Why HE Key Target Groups REACH Preparing for HE, for students with Autism and Asperger’s 4 Group Provider Activity Name Year 7 De Montfort University Problem Solving Year 8 De Montfort University Life Skills Year 9 University of Leicester -

Nyhagen, Loughborough

Muslim Women in Higher Education Institutions in Britain ESRC DTP Joint Studentship Loughborough University and Warwick University The Midlands Graduate School is an accredited Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Doctoral Training Partnership (DTP). One of 14 such partnerships in the UK, the Midlands Graduate School is a collaboration between the University of Warwick, Aston University, University of Birmingham, University of Leicester, Loughborough University and the University of Nottingham. We are now inviting applications for an ESRC Doctoral Joint Studentship between Loughborough University (where the student will be registered) and our partner Warwick University to commence in October 2021. The Project The PhD research project investigates opportunities and barriers to academic citizenship among Muslim women doctoral students, researchers and academics in British higher education institutions (HEIs). Citizenship is viewed in a broad sense and covers issues of recognition, participation and belonging. The project brings intersectional and spatial dimensions of HEIs to the fore in its analysis of Muslim women’s academic citizenship. The overall goal is to examine Muslim women’s experiences of barriers and opportunities, focusing on the career stages of PGRs, researchers and academics, with a view to producing policy-relevant knowledge that can support and enhance Muslim women’s participation, belonging and success in higher education institutions. Key research questions ask which institutional-level barriers and opportunities to academic research are experienced by Muslim women in HEIs; which individual-level and broader societal factors that may progress or hinder Muslim women’s academic careers in HEIs, and what best-practice policies and strategies can support Muslim women in HEIs. -

JAMES ROCKEY [email protected]

JAMES ROCKEY [email protected] http://www.jamesrockey.com Mailing Address: Contact Information: Astley Clarke Building Astley Clarke Building 210 University of Leicester Phone: +44 (0) 116 223 1237 University Road Mobile: +44 (0) 7775 760 607 Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK Personal Information: Born 6 May 1981, British Citizen Current Positions: 2016{ Associate Professor, University of Leicester 2016{ Associate Member, NICEP, University of Nottingham Previous Positions: 2013{2016 Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Leicester 2008{2013 Lectuer in Economics, University of Leicester 2007{2008 Teaching Assistant, University of Bristol 2007{2008 Research Assistant, CMPO, University of Bristol 2004{2007 Class Teacher, University of Bristol Education: Ph.D., Economics, University of Bristol, 2008 MSc., Economics, University of Bristol, 2003 BA, Politics, Philosophy, and Economics, Oxford University, 2002 Fields: Political Economy, Inequality, Growth and Development Publications: \Ideology and the Growth of Government" (with Andrew Pickering) The Review of Eco- nomics and Statistics, 93(3), 907{919, 2011 \Women's behavioural engagement with a masculine male heightens during the fertile win- dow: Evidence for the cycle shift hypothesis" (with Heather Flowe and Elizabeth Swords) Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(4), 285{290, 2012 \Reconsidering the Fiscal Effects of Constitutions" European Journal of Political Economy, 28(3), 313{323, 2012 \Ideology and the Size of US State Government" (with Andrew Pickering) Public Choice 156(3), 443{465, 2013 \Growth Econometrics for Agnostics and True Believers" (with Jonathan Temple) European Economic Review 81, January 2016, Pages 86-102 Working Papers: \Party Formation and Competition"(with Dan Ladley). Being Revised. \Negative Voters: Electoral Competition With Loss Aversion" (with Benjamin Lockwood). -

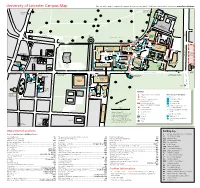

University of Leicester Campus Map Use Our Online Map to Explore the Campus Before You Leave and to Find Your Location When You Arrive

University of Leicester Campus Map Use our online map to explore the campus before you leave and to find your location when you arrive: www.le.ac.uk/maps To Victoria Park Health Centre To Brookfield Campus Victoria Park Pay and Display parki A5199 ng P n so Wing John g eldin South Fi Welford Road Car Park £ 3 2 1 To A6 Exit only To Train Station To Salisbury Road; To Freemen’s Common and London Road Nixon Court Houses (500m) 19 4 MAP KEY Campus entrance gate with barrier Wheelchair access information 5 Exit only Building access: Pre-booked parking for visitors – Full access to all floors please use entrance 1 Mostly accessible Occasional visitor parking – Ground floor only please check availability in advance Toilets accessible to wheelchair One-way system users within building Entrance to building Entrance suitable for wheelchair access Updated October 2017 £ Santander Bank Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey (R) Bus Stop Entrance with ramp 1:1250 maps with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Crossing Slope over 10% Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery P Parking Car parking space for disabled Office, (C) Crown copyright. University of drivers Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH. Café Licence number ED 100029495. To 106 New Walk Department Locations Building Key Please see building key for building references A Archaeology and Ancient History Building AC Astley Clarke Building AccessAbility Centre ..........................................................................................LIB European Law and Internationalisation, Centre for ..............................................FJ Physics and Astronomy ..................................................................................... PA Administration and Reception .............................................................................FJ Genetics and Genome Biology ....................................................................... ADR Politics and International Relations ................................................................. -

Cv1016-1.Pdf

James Rockey Department of Economics Office: (44) (0)-116-223-1237 University of Leicester Email: [email protected] University Road Homepage: jamesrockey.com/ Leicester, LE1 7RH UK Education Ph.D. Economics, University of Bristol, 2008. Dissertation: Essays on Political Economics Supervisor: Jonathan Temple; Examiners: Toke Aidt (Cambridge), and Frank Windmeijer (Bristol). MSc Economics, University of Bristol, 2003. BA Politics, Philosophy, and Economics, St Edmund Hall, Oxford University, 2002 Academic Experience University of Leicester, Department of Economics Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor August 2016 –), April 2013–present Lecturer (Assistant Professor), September 2008–April 2013. University of Bristol, Department of Economics Teaching Assistant, September 2007-July 2008 Research Assistant, Centre for Market and Public Organisation, Sept 2007- Aug 2008 Research Publications Ideology and the Growth of Government (with Andrew Pickering) The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(3), 907-919, 2011 Women’s behavioural engagement with a masculine male heightens during the fertile window: Evidence for the cycle shift hypothesis (with Heather Flowe and Elizabeth Swords) Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(4), 285-290, 2012 Reconsidering the Fiscal Effects of Constitutions European Journal of Political Economy, 28(3), 313-323, 2012 Ideology and the Size of US State Government (with Andrew Pickering) Public Choice 156(3), 443-465, 2013 Growth Econometrics for Agnostics and True Believers (with Jonathan Temple) European Economic Review