Mount Wilhelm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legacy of the German Language in Papua New Guinea T

Craig Alan Voll<er The legacy of the German language in Papua New Guinea t. lntroduction' German colonial rule in the western Pacific began formally in 1884 when unbe- known to them, people in north-eastern New Guinea (Ifuiser Wilhelmsland), the archipelago around the Bismarck Sea, and in the next year, almost ali of neigh- boring Micronesia were proclaimed to be under German "protection". This act changed ways of living that had existed for tens of thousands of years and laid the foundation for what eventually became the modern state of Papua New Guinea. This proclamation was made in German, a language that was then unknown to Melanesians and Micronesians. Today the German language is again mostly unknown to most Melanesians and only a few visible traces of any German colonial legacy remain. There are no old colonial buildings, no monuments outside of a few small and almost hidden cemeteries, and no German Clubs or public signs in German. In this century there has not even been a German embassy. But it is impossible to step out in New Ireland (the former "Neu-Mecklenburg"), for example, without being con- fronted by a twenty-first century reality that is in part a creation of German col- onial rule. Species that were introduced by the Germans stiil retain their German name, frorn clover,I(lee in both German and the local Nalik language to pineap- ples (GermanAnanas / Nalik ananas). The best rural road in the country the Bulominski Highway was started by and named after the last German governor of Neu-Mecklenburg and a mountain range is known as the Schleinitz Range. -

Los Cien Montes Más Prominentes Del Planeta D

LOS CIEN MONTES MÁS PROMINENTES DEL PLANETA D. Metzler, E. Jurgalski, J. de Ferranti, A. Maizlish Nº Nombre Alt. Prom. Situación Lat. Long. Collado de referencia Alt. Lat. Long. 1 MOUNT EVEREST 8848 8848 Nepal/Tibet (China) 27°59'18" 86°55'27" 0 2 ACONCAGUA 6962 6962 Argentina -32°39'12" -70°00'39" 0 3 DENALI / MOUNT McKINLEY 6194 6144 Alaska (USA) 63°04'12" -151°00'15" SSW of Rivas (Nicaragua) 50 11°23'03" -85°51'11" 4 KILIMANJARO (KIBO) 5895 5885 Tanzania -3°04'33" 37°21'06" near Suez Canal 10 30°33'21" 32°07'04" 5 COLON/BOLIVAR * 5775 5584 Colombia 10°50'21" -73°41'09" local 191 10°43'51" -72°57'37" 6 MOUNT LOGAN 5959 5250 Yukon (Canada) 60°34'00" -140°24’14“ Mentasta Pass 709 62°55'19" -143°40’08“ 7 PICO DE ORIZABA / CITLALTÉPETL 5636 4922 Mexico 19°01'48" -97°16'15" Champagne Pass 714 60°47'26" -136°25'15" 8 VINSON MASSIF 4892 4892 Antarctica -78°31’32“ -85°37’02“ 0 New Guinea (Indonesia, Irian 9 PUNCAK JAYA / CARSTENSZ PYRAMID 4884 4884 -4°03'48" 137°11'09" 0 Jaya) 10 EL'BRUS 5642 4741 Russia 43°21'12" 42°26'21" West Pakistan 901 26°33'39" 63°39'17" 11 MONT BLANC 4808 4695 France 45°49'57" 06°51'52" near Ozero Kubenskoye 113 60°42'12" c.37°07'46" 12 DAMAVAND 5610 4667 Iran 35°57'18" 52°06'36" South of Kaukasus 943 42°01'27" 43°29'54" 13 KLYUCHEVSKAYA 4750 4649 Kamchatka (Russia) 56°03'15" 160°38'27" 101 60°23'27" 163°53'09" 14 NANGA PARBAT 8125 4608 Pakistan 35°14'21" 74°35'27" Zoji La 3517 34°16'39" 75°28'16" 15 MAUNA KEA 4205 4205 Hawaii (USA) 19°49'14" -155°28’05“ 0 16 JENGISH CHOKUSU 7435 4144 Kyrghysztan/China 42°02'15" 80°07'30" -

Kosipe Revisited

Peat in the mountains of New Guinea G.S. Hope Department of Archaeology and Natural History, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY Peatlands are common in montane areas above 1,000 m in New Guinea and become extensive above 3,000 m in the subalpine zone. In the montane mires, swamp forests and grass or sedge fens predominate on swampy valley bottoms. These mires may be 4–8 m in depth and up to 30,000 years in age. In Papua New Guinea (PNG) there is about 2,250 km2 of montane peatland, and Papua Province (the Indonesian western half of the island) probably contains much more. Above 3,000 m, peat soils form under blanket bog on slopes as well as on valley floors. Vegetation types include cushion bog, grass bog and sedge fen. Typical peat depths are 0.5‒1 m on slopes, but valley floors and hollows contain up to 10 m of peat. The estimated total extent of mountain peatland is 14,800 km2 with 5,965 km2 in PNG and about 8,800 km2 in Papua Province. The stratigraphy, age structure and vegetation histories of 45 peatland or organic limnic sites above 750 m have been investigated since 1965. These record major vegetation shifts at 28,000, 17,000‒14,000 and 9,000 years ago and a variable history of human disturbance from 14,000 years ago with extensive clearance by the mid- Holocene at some sites. While montane peatlands were important agricultural centres in the Holocene, the introduction of new dryland crops has resulted in the abandonment of some peatlands in the last few centuries. -

Papua New Guinea Highlands and Mt Wilhelm 1978 Part 1

PAPUA NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS AND MT WILHELM 1978 PART 1 The predawn forest became alive with the melodic calls of unseen thrushes, and the piercing calls of distant parrots. The skies revealed the warmth of the morning dawn revealing thunderheads over the distant mountains that seemed to reach the melting stars as the night sky disappeared. I was 30 meters above the ground in a tree blind climbed before dawn. Swirling mists enshrouded the steep jungle canopy amidst a great diversity of forest trees. I was waiting for male lesser birds of paradise Paradisaea minor to come in to a tree lek next to the blind, where males compete for prominent perches and defend them from rivals. From these perch’s males display by clapping their wings and shaking their head. At sunrise, two male Lesser Birds-of-Paradise arrived, scuffled for the highest perch and called with a series of loud far-carrying cries that increase in intensity. They then displayed and bobbed their yellow-and-iridescent-green heads for attention, spreading their feathers wide and hopped about madly, singing a one-note tune. The birds then lowered their heads, continuing to display their billowing golden white plumage rising above their rust-red wings. A less dazzling female flew in and moved around between the males critically choosing one, mated, then flew off. I was privileged to have used a researcher study blind and see one of the most unique group of birds in the world endemic to Papua New Guinea and its nearby islands. Lesser bird of paradise lek near Mt Kaindi near Wau Ecology Institute Birds of paradise are in the crow family, with intelligent crow behavior, and with amazingly complex sexual mate behavior. -

The Climate of Mt Wilhelm RJ Hnatiuk JM B Smith D N Mcvean Mt Wilhelm Studies 2

Mt Wilhelm Studies 2 The Climate of Mt Wilhelm RJ Hnatiuk JM B Smith D N Mcvean Mt Wilhelm Studies 2 TheRJ Hnatiuk Climate JM B Smith of DMt N Mcvean Wilhelm Research School of Pacific Studies Department of Biogeography & Geomorphology Publication BG/4 The Australian National University, Canberra Printed and Published in Australia at The Australian National University 1976 National Library of Australia Card No. and I.S.B.N. 0 7081 1335 4 © 1976 Australian National University This Book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission . Printed at: SOCPAC Printery The Research Schools of Social Science and Pacific Studies H.C. Coombs Building, ANU Distributed for the Department by: The Australian National University Press The Climate of Mt Wilhelm PREFACE In 1966, the Australian National University with assistance from the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Hawaii, established a field station beside the lower Pindaunde Lake at an altitude of 3480 m on the south- east flank of Mt Wilhelm, the highest point in Papua New Guinea. The field station has been used by a number of workers in the natural sciences, many of whose publications are referred to later in this work. The present volume arises from observations made by three botanists and their collaborators when members of the Department of Biogeography and Geomorphology, during the course of their work on Mt Wilhelm while based on the ANU field station. It is the second in the Departmental series describing the environment and biota of the mountain, and will be followed by others dealing with different aspects of its natural history. -

PAPUA NEW GUINEA Ramu River Below Yonki Dam Spillway 1

PAPUA NEW GUINEA Ramu River below Yonki dam Spillway 1. COUNTRY INTRODUCTION Description: Economy: Located directly north of Australia and east of Papua New Guinea (PNG) has vast reserves of Indonesia, in between the Coral Sea and the natural resources, but exploitation has been South Pacific Ocean, Papua New Guinea (PNG) hampered by rugged terrain, land tenure issues, comprises several large high volcanic islands and and the high cost of developing infrastructure. numerous volcanic and coral atolls. PNG has the The economy is focused mainly on the extraction largest land area found within the Pacific Island and export of the abundant natural resources. Countries with an area of over 462,840kms2. The Mineral deposits, including copper, gold, and highest point is Mount Wilhelm at 4,509m. The oil, account for nearly two-thirds of the export land is characterised by densely forested steep earnings. Agriculture provides a subsistence catchments, where less than 0.5% of the land area livelihood for 85% of the people. Natural gas is considered arable with an estimated 1.4% of reserves amount to an estimated 227 billion cubic total the land used for permanent crops. meters. A consortium led by a major American oil company is constructing a liquefied natural The 2000 census data identifies a population gas (LNG) production facility that could begin of 5,190,786 (PNG, National Statistics Office), exporting in 2014. As the largest investment with an estimated 87% of the population project in the country’s history, it has the living in rural areas (Demography and Housing potential to double GDP in the near-term and survey, 2006). -

Squandering Paradise?

THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS SQUANDERING PARADISE? The importance and vulnerability of the world’s protected areas By Christine Carey, Nigel Dudley and Sue Stolton Published May 2000 By WWF-World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund) International, Gland, Switzerland Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above- mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © 2000, WWF - World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund) ® WWF Registered Trademark WWF's mission is to stop the degradation of the planet's natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by: · conserving the world's biological diversity · ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable · promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption Front cover photograph © Edward Parker, UK The photograph is of fire damage to a forest in the National Park near Andapa in Madagascar Cover design Helen Miller, HMD, UK 1 THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS Preface It would seem to be stating the obvious to say that protected areas are supposed to protect. When we hear about the establishment of a new national park or nature reserve we conservationists breathe a sigh of relief and assume that the biological and cultural values of another area are now secured. Unfortunately, this is not necessarily true. Protected areas that appear in government statistics and on maps are not always put in place on the ground. Many of those that do exist face a disheartening array of threats, ranging from the immediate impacts of poaching or illegal logging to subtle effects of air pollution or climate change. -

MOUNT WILHELM CLIMB Monday 10Th to Friday 14Th August 2015

MOUNT WILHELM CLIMB Monday 10th to Friday 14th August 2015 4509 meters (14793 feet) Mt Wilhelm is the highest mountain in Papua New Guinea and Oceania has rugged peaks with a well formed trail leading to its summit. The ascent crosses diverse and beautiful terrain with open grassland on the slopes and granite predominant in the higher levels. It is not a technical mountain to climb and takes 3 – 4 days to ascend. There are no ropes involved or high altitude gear or equipment required. You WILL feel the effects of altitude on Wilhelm. Although we do our very best to have a 100% success rate to the summit, safety is our highest priority. Safety will not be compromised under any circumstances. This mountain lends itself to all age groups and would expect anyone wanting to ascend to be in good physical condition. This day is twice had hard as any day on Kokoda. REMEMBER IT IS OPTIONAL TO GET TO THE TOP BUT COMPULSORY TO GET DOWN This has to be one of the most scenically spectacular areas of Papua New Guinea. The terrain is rugged and to see gardens on these steepest of slopes is truly amazing. We trek through three echo systems, tropical, temperate and alpine. You will see amazing wild orchids and trek through a savanna of cycads. If you want to truly experience the highlands of Papua New Guinea this is a must do trek. If you don’t want to climb the mountain take the leisurely walk to base camp or you may chose to stay at the Lodge which is a remarkable experience in itself. -

Where the Trees Disappear, the Alpines Begin, Rich in Growth Forms of the Low-Bush Downloaded by Guest on September 25, 2021 VOL

860 BOTANY: J. CLAUSEN PROC. N. A. S. 20 hr. The same would not be true, however, if both groups of cells were exposed to 200 r/day. Summary.-Experiments were performed with seedlings of Pisum sativum to test the hypothesis that radiosensitivity with respect to chromosome damage in- creases during chronic irradiation with increased mitotic cycle time. Mlinimum cycle times were determined for root meristem cells. Temperatures of 300, 250, 150, and 100C were used to obtain different minimum cycle times. The results of chronic exposures indicated that (1) the minimum cycle time was not altered in Pisum sativum until the total exposure per cycle exceeded about 440-450 r; (2) the percentage of cells showing damaged chromosomes at a stated daily exposure rate increased with decreasing temperatures if mitotic cycle time was not con- sidered; but (3) when the cycle time is taken into account, the production of dam- aged cells is a linear function of the amount of total exposure per mitotic cycle up to the critical value 440-450 r/cycle. The authors wish to thank Dr. D. Roy Davies and Mrs. Rhoda C. Sparrow for discussions and suggestions concerning this manuscript, and Dr. Keith Thompson for performing the necessary statistical analyses. * Research was carried out at Brookhaven National Laboratory under the auspices of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. I Sparrow, A. H., and H. J. Evans, in Fundamental Aspects of Radiosensitivity, Brookhaven Symposia in Biology, No. 14 (1961), p. 76. 2 Sparrow, A. H., R. L. Cuany, J. P. Miksche, and L. A. Schairer, Radiation Botany, 1, 10 (1961). -

Chapter 7 Australasia

Chapter 7 Australasia Three large islands east of Timor Trough and Aru and Allen 1988). The prominent peaks are the Basin constitute Asia’s farthest region of Australa- Puncak Jaya (Mt. Victory at 5,029m) in the west sia. Australia, its main bulk, can be described as and Mount Wilhelm (4,697m) in the east. The the world’s largest island and smallest continent. former, originally called Mount Carstenz after a The other two island groups are New Guinea in Dutch navigator, is high enough to support some the north and New Zealand in the south-east. small glaciers. The western section in Indonesia, Australia and New Guinea are only separated by Pegunungan Maoke, has three other peaks over the shallow Arafura Sea but present a contrast in 4,500m in elevation. The eastern section in Papua geological structure. Australia is mostly founded New Guinea extends from Thurnwald through the on Precambrian stable shield related to Gondwana Bismarck to Owen Stanley Ranges in the extreme land. New Guinea, on the other hand, has east- east. As a general pattern, the highlands have the west axes of Tertiary folding. New Zealand is simi- steepest slopes towards the south. Along the north- larly built on a folded structure but aligned south- ern coast are a chain of lower ranges that trend west/north-east (Figure 8 and Annex F). parallel to the main range. These are the Van Rees in the west, Torricelli in the middle, and Finisterre 7.1 New Guinea in the east. The main highlands are composed of Archaean schists and massive crystallines with lava The island of New Guinea is comprised of the In- effusives in the central part. -

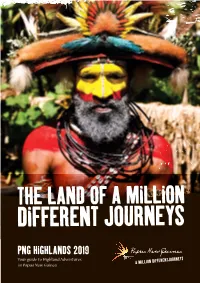

PNG HIGHLANDS 2019 Your Guide to Highland Adventures in Papua New Guinea

PNG HIGHLANDS 2019 Your guide to Highland Adventures in Papua New Guinea EQUATOR EQUATOR EQUATOR EQUATOR 144ºE 148ºE 152ºE 156ºE E º 144 E º 156 E º 152 E º 148 0º º 0 0km 62.5 125 187.5 250km 0km 62.5 125 187.5 250km 187.5 125 62.5 0km KEY KEY NEW GUINEA ISLANDS REGION ISLANDS GUINEA NEW MANUS NEW GUINEA ISLANDS REGION MANUS Ninigo Ninigo M M Bird Watching Bird Bird Watching u us s Admiralty Admiralty Group Group s s a au u Islands Islands I Is s l l a a Tabalo Tabalo Cruising Aua I. Cruising Aua I. Aua n n Mussau Mussau d Hermit Is. d Hermit Is. Hermit s s Pala Kau Pala Pala Kau Wuvulu I. Wuvulu I. Wuvulu Eloaua Eloaua Cycling Cycling Emirau Emirau SOUTH SOUTH Tong Tong Liap Liap Manus Manus Kabuli Kabuli Diving Diving Lorengau Lorengau Western I. Western Western I. North North PACIFIC PACIFIC SANDAUN SANDAUN EAST SEPIK EAST SEPIK EAST Rambutyo Rambutyo Noipuops Noipuops Cape Cape Lou Lou Fishing Fishing Fishing Umbukul Umbukul Taskul Taskul Kavieng Kavieng OCEAN OCEAN New New Purdy Is. Purdy Purdy Is. Kaut Hanover Kaut Hanover Tabar Is. Tabar Tabar Is. Kayaking Kayaking Vanimo Vanimo Alim Alim Laefu Dyaul Laefu Dyaul Sissano Sissano Lihir Group Lihir Group Lihir Konos Konos Vokeo Vokeo Walis Walis 1617 1617 Aitape Aitape Kite Surfing Kite Kite Surfing S Sc c h h Kairiru Kairiru o o u u N N t t 1481 1481 e e Bismarck Bismarck n n Dagua Dagua e e I I Mushu Mushu w w s s. -

Land Module of Our Planet Reviewed - Papua New Guinea: Aims, Methods and First Taxonomical Results

Mount Wilhelm summit (4507 m a.s.l.) (Photo by T. Fayle) OUR PLANET REVIEWED – PAPUA NEW GUINEA 13 Land module of Our Planet Reviewed - Papua New Guinea: aims, methods and first taxonomical results Maurice Leponce (1), Vojtech Novotny (2, 3), Olivier Pascal (4), Tony Robillard (5), Frederic Legendre (5), Claire Villemant (5), Jérôme Munzinger (6), Jean-François Molino (6), Richard Drew (7), Frode Odegaard (8), Jürgen Schmidl (9), Alexey Tishechkin (17), Katerina Sam (3), Daniel Bickel (10), Chris Dahl (2, 3), Kipiro Damas (11), Tom M. Fayle (12, 2, 3), Bradley Gewa (2), Justine Jacquemin (1), Martin Keltim (2), Petr Klimes (2, 3) Bonny Koane (2), Joseph Kua (2), Antoine Mantilleri (5), Martin Mogia (2), Kenneth Molem (2), Jimmy Moses (2, 3) Hans Nowatuo (2), Jérôme Orivel (13), †Jean-Christophe Pintaud (14), Yves Roisin (15), Legi Sam (2, 3), Byron Siki (2), Laurent Soldati (16), Adeline Soulier-Perkins (5), Salape Tulai (2), Jacob Yombai (2), Carl Wardhaugh (3), Yves Basset (3, 18) (1) Biodiversity Monitoring & Assessment unit, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, 29 rue Vautier, 1000 Brussels, Belgium, [email protected] (2) The New Guinea Binatang Research Center, Nagada Harbour, P. O. Box 604, Madang, Papua New Guinea (3) Biology Center, Czech Academy of Sciences and Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branisovska 31, 370 05 Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic (4) Pro-Natura International, 15 avenue de Ségur 75007 Paris, France (5) Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité, UMR 7205 CNRS-MNHN-UPMC-EPHE, Sorbonne Universités, 45 rue Buffon, F-75005 Paris, France (6) IRD, UMR AMAP, Bd de la Lironde TA A51 / PS2, 34398 Montpellier cedex 5, France (7) International Centre for the Management of Pest fruit Flies, Griffith School of Environment, Nathan campus, Griffith University, 170 Kessels Road, Nathan, Brisbane, Queensland 4111, Australia (8) Norwegian Institute for Nature Research – NINA, Box: 5685 Sluppen NO-7485 Trondheim, Norway (9) Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, staudtstr.