Wildlife Conservation Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flat-Headed Cat (Prionailurus Planiceps)

12/02/2019 Flat-headed cat factsheet on Arkive - Prionailurus planiceps Flat-headed cat (Prionailurus planiceps) French: Chat À Tête Plate Spanish: Gato Cabeciancho Kingdom Animalia Phylum Chordata Class Mammalia Order Carnivora Family Felidae Genus Prionailurus (1) Size Male head-and-body length: 42 – 50 cm (2) Female head-and-body length: 33 – 37 cm ( 2) Male tail length: 13 – 20 cm (2) Female tail length: 15 – 17 cm ( 2) Male weight: 1.5 – 2.75 kg (2) Female weight: 1.5 kg (2) Classified as Endangered (EN) on the IUCN Red List (1), and listed on Appendix I of CITES (3). Its distinctly elongated, flattened head and small, rounded ears, make this unusual member of the cat family bear a strong resemblance to the civets, which are not cats, but members of the Viverridae family (4) (5). About the size of a domestic cat, the flat-headed cat has a long body, short legs and a short, thickly-furred tail (5). Even more than the fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrina), the flat-headed cat appears remarkably adapted to a semi-aquatic, fish-eating lifestyle (6). Partial webbing between the toes help the animal to move through water, and the long, narrow jaws and pointed, backward-facing teeth aid the catching and holding of slippery prey such as fish and frogs. The thick, soft coat is reddish-brown on the top of the head and dark brown on the body, finely speckled with grey and buff on the tips (5). The belly is mottled white, spotted and splashed with brown, and the insides of the limbs are reddish-brown, fading towards the feet (2). -

(Prionailurus Viverrinus) at Peam Krasaop Wildlife Sanctuary, South West Cambodia

Bas-relief on Bayon Temple, possibly representing a Fishing Cat swimming. Conservation of a newly recorded population of Fishing Cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) at Peam Krasaop Wildlife Sanctuary, south west Cambodia. www.fishingcatcambodia.org Kla Trey Cambodian Fishing Cat Project Conservation of a newly recorded population of Fishing Cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) at Peam Krasaop Wildlife Sanctuary, south west Cambodia. www.fishingcatcambodia.org ProjecT summAry Categorised as Endangered (EN) on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, the Fishing Cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) had only been recorded through camera-trapping once in Cambodia. Fishing cats have declined sharply across South-East Asia where, according to the Fishing Cat Working Group, there might be new populations still to be found but the species could also be approaching extinction. In 2015, the CBC recorded1 Fishing Cats at two sites with no previous records in south-west Cambodia: Peam Krosaop Wildlife Sanctuary (PKWS) and Ream National Park (RNP). We photo-captured two individuals at PKWS, one of the largest mangrove areas in South-East Asia. We were also informed of the killing of a Fishing Cat at PKWS soon after the study was completed in retaliation for raiding fishing nets. This project seeks to estimate population abundance and status in PKWS, assess threats and work with all the relevant stakeholders to develop conservation measures to protect this newly found Fishing Cat population. The Team ProjecT Advisors Principal Investigator: Vanessa Herranz Muñoz. She participated in the 2015 CBC Fishing Cat survey as Consultant. The Kla Trey | Cambodian Fishing Cat Project research will form her PhD from the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Spain). -

Fishing Cat Conservation and Research Project

Cat Project of the Month – December 2009 The IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group's website (www.catsg.org) presents each month a different cat conservation project. Members of the Cat Specialist Group are encouraged to submit a short description of interesting projects Fishing Cat Conservation and Research Project The Fishing Cat Research and Conservation Project identifies viable populations of fishing cats in Southeast Asia supports direct action to conserve those populations. The project does this by conducting field research, supporting effective habitat management, and by initiating and supporting education and outreach activities. Namfon Cutter is the director of this project and is currently conducting field research as part of a MSc. Degree program in the University of Minnesota’s Conservation Biology Graduate Program. Namfon has been a member of the Cat SG since fall 2009. namfon@conservation asia.org Passanan Cutter, submitted: November 2009 project PI (Photo P. Cutter) Detail from a poster inviting the public to get to know more about the kodkod cat (Photo F. Vidal). Background The Fishing Cat Research and Conservation Project has four components, each contributing to fishing cat conservation in Thailand and throughout Southeast Asia. • The first of these is a regional review of fishing cat distribution and conservation status involving the compilation of all current and historical data on fishing cat occurrence throughout Southeast Asia. • The project's second component is a detailed ecological study of fishing cats in their natural habitat. This component of the project will provide biologists with a solid foundation upon which to plan subsequent ecological research and conservation efforts. -

The Wildlife Snaring Crisis: an Insidious and Pervasive Threat to Biodiversity in Southeast Asia

Biodivers Conserv (2018) 27:1031–1037 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1450-5 COMMENTARY The wildlife snaring crisis: an insidious and pervasive threat to biodiversity in Southeast Asia 1 2 3 Thomas N. E. Gray • Alice C. Hughes • William F. Laurance • 4 5 6 Barney Long • Anthony J. Lynam • Hannah O’Kelly • 7 8 9 William J. Ripple • Teak Seng • Lorraine Scotson • Nicholas M. Wilkinson10 Received: 12 April 2017 / Revised: 30 September 2017 / Accepted: 11 October 2017 / Published online: 14 October 2017 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2017 Abstract Southeast Asia, a region supporting more threatened species than any other comparable continental area, is in the midst of a conservation crisis. Hunting constitutes the greatest current threat to the region’s threatened vertebrates and has resulted in many areas of largely intact forest losing much of their former vertebrate diversity and abun- dance. Though numerous hunting methods are used, capture with home-made snares is a major driver of this defaunation. Snares are cheaply constructed and easy to set but can be difficult to detect and are highly damaging to vertebrate populations due to their indis- criminate and wasteful nature. The primary response to snaring is the removal of snares by patrol teams: more than 200,000 snares were removed from just five of the region’s Communicated by David Hawksworth. & Thomas N. E. Gray [email protected] 1 Wildlife Alliance, Toul Tompong I, No. 86, Street 123, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 2 Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Jinghong, China 3 Centre for Tropical Environmental and Sustainability Science and College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Cairns, Australia 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, Austin, TX, USA 5 Wildlife Conservation Society, Center for Global Conservation, Bronx, NY, USA 6 Vientiane, Lao PDR 7 Global Trophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA 8 World Wildlife Fund Greater Mekong, Boueng Keng Kang I, No. -

Hybrid Cats’ Position Statement, Hybrid Cats Dated January 2010

NEWS & VIEWS AAFP Position Statement This Position Statement by the AAFP supersedes the AAFP’s earlier ‘Hybrid cats’ Position Statement, Hybrid cats dated January 2010. The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) strongly opposes the breeding of non-domestic cats to domestic cats and discourages ownership of early generation hybrid cats, due to concerns for public safety and animal welfare issues. Unnatural breeding between intended mates can make The AAFP strongly opposes breeding difficult. the unnatural breeding of non- Domestic cats have 38 domestic to domestic cats. This chromosomes, and most commonly includes both natural breeding bred non-domestic cats have 36 and artificial insemination. chromosomes. This chromosomal The AAFP opposes the discrepancy leads to difficulties unlicensed ownership of non- in producing live births. Gestation domestic cats (see AAFP’s periods often differ, so those ‘Ownership of non-domestic felids’ kittens may be born premature statement at catvets.com). The and undersized, if they even AAFP recognizes that the offspring survive. A domestic cat foster of cats bred between domestic mother is sometimes required cats and non-domestic (wild) cats to rear hybrid kittens because are gaining in popularity due to wild females may reject premature their novelty and beauty. or undersized kittens. Early There are two commonly seen generation males are usually hybrid cats. The Bengal (Figure 1), sterile, as are some females. with its spotted coat, is perhaps The first generation (F1) female the most popular hybrid, having its offspring of a domestic cat bred to origins in the 1960s. The Bengal a wild cat must then be mated back is a cross between the domestic to a domestic male (producing F2), cat and the Asian Leopard Cat. -

Small Carnivores of Karnataka: Distribution and Sight Records1

Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 104 (2), May-Aug 2007 155-162 SMALL CARNIVORES OF KARNATAKA SMALL CARNIVORES OF KARNATAKA: DISTRIBUTION AND SIGHT RECORDS1 H.N. KUMARA2,3 AND MEWA SINGH2,4 1Accepted November 2006 2 Biopsychology Laboratory, University of Mysore, Mysore 570 006, Karnataka, India. 3Email: [email protected] 4Email: [email protected] During a study from November 2001 to July 2004 on ecology and status of wild mammals in Karnataka, we sighted 143 animals belonging to 11 species of small carnivores of about 17 species that are expected to occur in the state of Karnataka. The sighted species included Leopard Cat, Rustyspotted Cat, Jungle Cat, Small Indian Civet, Asian Palm Civet, Brown Palm Civet, Common Mongoose, Ruddy Mongoose, Stripe-necked Mongoose and unidentified species of Otters. Malabar Civet, Fishing Cat, Brown Mongoose, Nilgiri Marten, and Ratel were not sighted during this study. The Western Ghats alone account for thirteen species of small carnivores of which six are endemic. The sighting of Rustyspotted Cat is the first report from Karnataka. Habitat loss and hunting are the major threats for the small carnivore survival in nature. The Small Indian Civet is exploited for commercial purpose. Hunting technique varies from guns to specially devised traps, and hunting of all the small carnivore species is common in the State. Key words: Felidae, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Mustelidae, Karnataka, threats INTRODUCTION (Mukherjee 1989; Mudappa 2001; Rajamani et al. 2003; Mukherjee et al. 2004). Other than these studies, most of the Mammals of the families Felidae, Viverridae, information on these animals comes from anecdotes or sight Herpestidae, Mustelidae and Procyonidae are generally records, which no doubt, have significantly contributed in called small carnivores. -

Mixed Species Rotation Exhibits", 2004 ARAZPA Conference Proceedings, Australia, on CD

Coe, Jon C. 2004, ”Mixed Species Rotation Exhibits", 2004 ARAZPA Conference Proceedings, Australia, on CD. Mixed Species Rotation Exhibits Jon Coe Jon Coe Design Pty Ltd [email protected] Abstract Immersion exhibits have changed animal zoo exhibition using “nature” as the model for international best practice, yet even the most diverse zoo habitats don’t provide animals occupations and animals soon become habituated with resulting decrease in animal activity and visual interest for the public. Activity-based design merges immersion displays with behavioural management to increase novelty and species-typical activities. At the Louisville, Kentucky (USA) Islands Exhibits orangutan, tapir, babirusa, siamang and Sumatran tiger rotate through four habitat areas on a randomly determined schedule. Five years of behavioural observations show normal stress levels, increased activity and previously unseen natural behaviours. Introduction to Animal Rotation How can we increase healthy animal activity and visitor interest while helping improve staff skills? Animal rotation displays can provide these benefits. I first introduced the concept of animal rotation displays in 1995 as one example of what my colleagues and I called Activity-Based Design and Management (Coe 1995, 1997). The central idea was to fully integrate the commonly disparate practices of husbandry, design, behavioural management and behavioural enrichment for the benefit of animals, staff and visitor alike. Readers interested in more background are referred to these papers. Since then a number of new animal rotation facilities have been built and operated and several more are being planned. It is time to devote a paper to the specific subject of animal rotation exhibits themselves. -

Survey of the Fishing Cat Prionailurus Viverrinus Bennett, 1833 (Carnivora: Felidae) and Some Aspects Impacting Its Conservation in India

JoTT SHORT COMMUNI C ATION 4(14): 3355–3361 Survey of the Fishing Cat Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 (Carnivora: Felidae) and some aspects impacting its conservation in India Shomita Mukherjee 1, Tiasa Adhya 2, Prachi Thatte 3 & Uma Ramakrishnan 4 1 Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Annaikatty Post, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641108, India 2,3,4 National Centre for Biological Sciences, GKVK Campus, Bellary Road, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560065, India Email: 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected], 4 [email protected] The Fishing Cat Prionailurus viverrinus is one of the Abstract: The Fishing Cat Prionailurus viverrinus is a medium sized cat that is widely but patchily distributed across Asia and 15 felids that inhabit India (Nowell & Jackson 1996). strongly associated with wetlands. It is among the 15 felid Like the other small cats in the country, little is known species that inhabit India and like other smaller cat species it is very poorly understood. Apart from a few recent surveys in about its ecology and conservation status. Existing specific locations, no concerted effort has been made to assess knowledge on distribution and behaviour is based on its current distribution and threats to its persistence within India. observations mainly done many decades ago (Pocock In this study we collected scats from natural habitats, through six states including five protected areas throughout India and 1939; Nowell & Jackson 1996; Sunquist & Sunquist performed informal interviews with locals to get a better overview 2002), with only a few serious systematic efforts into of the current distribution and threats for Fishing Cats in India. -

Flat Headed Cat Andean Mountain Cat Discover the World's 33 Small

Meet the Small Cats Discover the world’s 33 small cat species, found on 5 of the globe’s 7 continents. AMERICAS Weight Diet AFRICA Weight Diet 4kg; 8 lbs Andean Mountain Cat African Golden Cat 6-16 kg; 13-35 lbs Leopardus jacobita (single male) Caracal aurata Bobcat 4-18 kg; 9-39 lbs African Wildcat 2-7 kg; 4-15 lbs Lynx rufus Felis lybica Canadian Lynx 5-17 kg; 11-37 lbs Black Footed Cat 1-2 kg; 2-4 lbs Lynx canadensis Felis nigripes Georoys' Cat 3-7 kg; 7-15 lbs Caracal 7-26 kg; 16-57 lbs Leopardus georoyi Caracal caracal Güiña 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Sand Cat 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus guigna Felis margarita Jaguarundi 4-7 kg; 9-15 lbs Serval 6-18 kg; 13-39 lbs Herpailurus yagouaroundi Leptailurus serval Margay 3-4 kg; 7-9 lbs Leopardus wiedii EUROPE Weight Diet Ocelot 7-18 kg; 16-39 lbs Leopardus pardalis Eurasian Lynx 13-29 kg; 29-64 lbs Lynx lynx Oncilla 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus tigrinus European Wildcat 2-7 kg; 4-15 lbs Felis silvestris Pampas Cat 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus colocola Iberian Lynx 9-15 kg; 20-33 lbs Lynx pardinus Southern Tigrina 1-3 kg; 2-6 lbs Leopardus guttulus ASIA Weight Diet Weight Diet Asian Golden Cat 9-15 kg; 20-33 lbs Leopard Cat 1-7 kg; 2-15 lbs Catopuma temminckii Prionailurus bengalensis 2 kg; 4 lbs Bornean Bay Cat Marbled Cat 3-5 kg; 7-11 lbs Pardofelis badia (emaciated female) Pardofelis marmorata Chinese Mountain Cat 7-9 kg; 16-19 lbs Pallas's Cat 3-5 kg; 7-11 lbs Felis bieti Otocolobus manul Fishing Cat 6-16 kg; 14-35 lbs Rusty-Spotted Cat 1-2 kg; 2-4 lbs Prionailurus viverrinus Prionailurus rubiginosus Flat -

Fishing Cat • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • Prionailurus Viverrinus

Fishing Cat • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • Prionailurus viverrinus Classification What groups does this organism belong to based on characteristics shared with other organisms? Class: Mammalia (all mammals) Order: Carnivora (carnivores) Family: Felidae (cats) Genus: Prionailurus (Asian small cats) Species: Prionailurus viverrinus (fishing cat) Distribution Where in the world does this species live? Fishing cats are found in scattered areas throughout Asia. They inhabit the peninsular region of India, and areas of Southeast Asia including, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Sumatra, Thailand, Java, and Pakistan. Habitat What kinds of areas does this species live in? Fishing cats live primarily in wetland areas, both marshes and swamps. These cats can be found in heavily forested regions adjacent to rivers or near jungles. They can also be found in scrub areas, reed beds, tidal creek, and mangrove areas. In the Nepalese lowlands some individual fishing cats spend a lot of time in dense grasslands well away from water. Physical Description How would this animal’s body shape and size be described? • Fishing cats are considered one of the largest of the lesser cats. Adults can weigh 13 to 26 lb (6- 12 kg) and measure 2-3 feet long (0.6-1 m). • Fishing cats are powerfully built with short limbs and a stocky body. • They have a long head and a short tail that is roughly one-third the length of their body. • Their fur is coarse and brownish gray in color with distinctive dark markings, which are a combination of both spots and stripes. These spots are arranged longitudinally across the body. Six to eight dark lines run from above the eyes between the ears over the crown to the nape of the neck. -

Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species

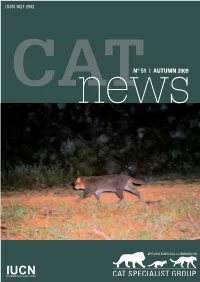

ISSN 1027-2992 CATnewsN° 51 | AUTUMN 2009 01 IUCNThe WorldCATnews Conservation 51Union Autumn 2009 news from around the world KRISTIN NOWELL1 Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species The IUCN Red List is the most authoritative lists participating in the assessment pro- global index to biodiversity status and is the cess. Distribution maps were updated and flagship product of the IUCN Species Survi- for the first time are being included on the val Commission and its supporting partners. Red List website (www.iucnredlist.org). Tex- As part of a recent multi-year effort to re- tual species accounts were also completely assess all mammalian species, the family re-written. A number of subspecies have Felidae was comprehensively re-evaluated been included, although a comprehensive in 2007-2008. A workshop was held at the evaluation was not possible (Nowell et al Oxford Felid Biology and Conservation Con- 2007). The 2008 Red List was launched at The fishing cat is one of the two species ference (Nowell et al. 2007), and follow-up IUCN’s World Conservation Congress in Bar- that had to be uplisted to Endangered by email with others led to over 70 specia- celona, Spain, and since then small changes (Photo A. Sliwa). Table 1. Felid species on the 2009 Red List. CATEGORY Common name Scientific name Criteria CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus C2a(i) ENDANGERED (EN) Andean cat Leopardus jacobita C2a(i) Tiger Panthera tigris A2bcd, A4bcd, C1, C2a(i) Snow leopard Panthera uncia C1 Borneo bay cat Pardofelis badia C1 Flat-headed -

Albinism in the Fishing Cat (Prionailurus Viverrinus) from the Haor Basin of Bangladesh

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235968719 Albinism in the fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) from the Haor Basin of Bangladesh Article · January 2013 CITATION READS 1 98 3 authors, including: Anthony J. Giordano Mohammed Feeroz Texas Tech University Jahangirnagar University 82 PUBLICATIONS 212 CITATIONS 69 PUBLICATIONS 383 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Rarest Cat in the World? Assessing the Conservation Status of the Javan Fishing Cat View project All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate, Available from: Anthony J. Giordano letting you access and read them immediately. Retrieved on: 01 October 2016 ISSN 1027-2992 CATnewsN° 58 | SPRING 2013 01 CATnews 58 Spring 2013 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser a component of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the Co-chairs IUCN/SSC International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is pub- Cat Specialist Group lished twice a year, and is available to members and the Friends of KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, the Cat Group. Switzerland Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] <[email protected]> <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send contributions and observations to Associate Editors: Keith Richmond [email protected]. Brian Bertram Sultana Bashir Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Javier Pereira CATnews is produced with financial assistance from Friends of Cover Photo: First photographic evidence the Cat Group.