The Other Sophia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

SANCTUARY Set ONE Sweet Freedom

SANCTUARY Set ONE Sweet Freedom Adapted from My Country,Tis of Thee Let music swell the breeze, Arr. by Gwyneth Walker And ring from all the trees, Sweet, sweet, sweet freedom, freedom song My country, ‘tis of thee, Sweet land of liberty Let freedom ring, O, (x2) Of thee I sing; Land where my fathers died, land of my mother’s Let mortal tongues awake, Let all that breathes pride partake; From ev’ry mountain side let freedom ring Let rocks, let rocks their silence break; Let freedom ring, O, (x6) The sound, the sound prolong Let freedom ring, O, (x4) My native country thee, Land of the noble free, Thy name, they name, I love My country (5x) Let freedom ring, O, (x2) let freedom ring, O, Let freedom ring, O let freedom ring, O, Let freedom ring, O. I love they rocks and rills, let freedom ring, O Thy woods and templed hills; My country, my country, my country My heart, my heart, with rapture fills Let freedom ring, let freedom ring! Will joy like that above Let freedom ring, O, (x4) 1 How Lovely is Thy Dwelling Place Isle of Hope, Isle of Tears Music and lyrics by Johannes Brahms, from his Music and lyrics by Brendan Graham, arr. by John German Requiem Leavitt How lovely is thy dwelling place, O Lord of Hosts, O On the first day of January, eighteen ninety-two, Lord of Hosts they opened Ellis Island and they let the people Thy dwelling place, O Lord of Hosts through. How lovely is thy dwelling place, O Lord of Hosts And the first to cross the threshold of the isle of How lovely is thy dwelling place, O Lord of Hosts! hope and tears was Annie Moore from Ireland who was all of For my soul, it longeth, yea fainteth for the courts fifteen years of the Lord Chorus: My soul and body crieth out, yea for the living God Isle of hope, isle of tears, isle of freedom, isle of My soul and body crieth out, yea for the living,yea fears. -

Wholly Innocent

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 12-19-2008 Wholly Innocent James Wesley Harris University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Harris, James Wesley, "Wholly Innocent" (2008). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 873. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/873 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wholly Innocent A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by James Wesley Harris B.A. Saint Louis University, 1998 December, 2008 Copyright 2008, James Wesley Harris ii Acknowledgements I thank my parents, Bill and Amelie Harris, without whom the central subject of this thesis, my life, would not exist. I especially thank Mom for endowing me with a vivid imagination, and Dad a steady work ethic. -

Songfest 2008 Book of Words

A Book of Words Created and edited by David TriPPett SongFest 2008 A Book of Words The SongFest Book of Words , a visionary Project of Graham Johnson, will be inaugurated by SongFest in 2008. The Book will be both a handy resource for all those attending the master classes as well as a handsome memento of the summer's work. The texts of the songs Performed in classes and concerts, including those in English, will be Printed in the Book . Translations will be Provided for those not in English. Thumbnail sketches of Poets and translations for the Echoes of Musto in Lieder, Mélodie and English Song classes, comPiled and written by David TriPPett will enhance the Book . With this anthology of Poems, ParticiPants can gain so much more in listening to their colleagues and sharing mutually in the insights and interPretative ideas of the grouP. There will be no need for either ParticiPating singers or members of the audience to remain uninformed concerning what the songs are about. All attendees of the classes and concerts will have a significantly greater educational and musical exPerience by having word-by-word details of the texts at their fingertiPs. It is an exciting Project to begin building a comPrehensive database of SongFest song texts. SPecific rePertoire to be included will be chosen by Graham Johnson together with other faculty, and with regard to choices by the Performing fellows of SongFest 2008. All 2008 Performers’ names will be included in the Book . SongFest Book of Words devised by Graham Johnson Poet biograPhies by David TriPPett Programs researched and edited by John Steele Ritter SongFest 2008 Table of Contents Songfest 2008 Concerts . -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

2004 06 13 Grateful for It All Mark Belletini Opening Words We Are

2004 06 13 Grateful for it All Mark Belletini Opening Words We are here to celebrate with gratitude, to rejoice we are all still learners in the school of life. We praise the gift of another morning, opening our arms to receive summer’s warmth which announces its coming in advance. Glad for this, our time of worship, we pray with words and our lives: May we live fully, love deeply, learn daily and speak truly that we might together leave the sacred legacy of a better world. Sequence The chicory flowers are grabbing pieces of the blue sky again, and anchoring them onto earth so we can marvel up close… the human dignitaries have all returned home from the national cathedral, but the robins are still here locally, as well as a handful of sparrows; plenty of dignity there! And the gothic arches of maple and oak are beautifully darkened by the week’s rain. O World, you never stop, you always astonish, you hold nothing back! What can I offer you in thanks but a small portion of the Silence that once gave birth to you, as you once gave birth to me… silence 1 Remembering those we love, those who walk the earth with us still, and those who now stroll in the meadows of our heart, we take pleasure in sounding their names inside us. Or, in the common air, either as we wish, adding the astonishment of their presence in our lives to the marvel of everything else… naming How grateful I am! The sun rises again, day after day, morning after morning…and illumines the precious minutes of my life on earth, and the lives of all people on earth, very young and very old, the well and the sick, the joyous and the sad. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Lyrics by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul

begins not with music, have a single person to whom we can actually speak. We but with noise. As the house lights fade, the audience envisioned two families, each broken in its own way, and is immersed momentarily in the roar of the internet: a two sons, both of them lost, both of them desperate to cacophony of car insurance ads, cat videos, scattered be found. And at the heart of our story, in a world starving shards of emails and text messages and status updates. for connection, we began to imagine a character utterly And then, all at once: silence. On stage, in the white glow incapable of connecting. of a laptop, a boy sits in his bedroom, alone. Though many of the rudiments of the character were Like so many of us, Evan is a citizen of two different already in place by the end of 2011, Evan didn’t fully come worlds, two distinct realities separated by the thin veil of a to life for me until almost two years into the process, when laptop screen. On one side of the screen, the promise of Benj and Justin emailed me a homemade demo of a song instant connection. On the other, a lonely kid, staring at a they were tentatively calling “Waving Back At Me.” blinking cursor, as desperate to be noticed as he is to stay This was to become “Waving Through a Window,” hidden. Evan’s first sung moment in the musical, when we see, Benj Pasek, Justin Paul, and I first began to create with incredible vividness, how the world looks through the the character of Evan over several months in 2011. -

Poco Loco Song List Newly Added Music Classic Pop / Dance

Poco Loco Song List Newly added Music Just the way you are - Bruno Mars Break even - The Script Closer - Chris Brown Love Story - Taylor Swift Forget you - Cee Lo Green Cry for you - September Pack up - Eliza Doolittle The boy does nothing - Alesha Dixon OMG - Usher Mercy - Duffy I've got a feeling - Black eyed Peas Rain - Dragon Bad Romance - Lady Ga Ga Dakota - Stereophonics Poker face - Lady Ga Ga California Gurls - Katy Perry Alejandro - Lady Ga Ga Don't hold Back - Pot Beleez I'm yours - Jason Mraz Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon Hey Soul Sister - Train Like it like that - Guy Sebastian Escape(The Pina Colada Song Smile - Uncle Kracker Sweet about me - Gabriella Cilma Save the lies - Gabriella Cilmi Apologize - One Republic Black and Gold - Sam Sparro Classic Pop / Dance A little less conversation - Elvis Let's dance - Chris Rea Addicted to Bass - Amiel Let's get the party started - Pink Ain't nobody - Chaka Khan Let's groove tonight - Earth wind n fire All I wanna do - Sheryl Crow Lets hear it for the boy - Denise Williams Amazing - George Michael Let's stick together - Bryan Ferry Angels - Robbie Williams Life is a rollercoaster - Ronan Keating Another Saturday night - Sam Cook Love at first sight - Kylie Minogue Around the the world - Lisa Stanfield Love fool - Cardigans Baby did a bad bad thing - Chris Isaac Love foolosophy - Jamiroquai Bad girls - Donna Summer love is in the air - John Paul Young Beautiful - Disco Montego Love really hurts without you - Billy Ocean Believe - Cher Love shack - B52's Bette Davis eyes - Kim Carnes -

The Mix Song List

THE MIX SONG LIST CONTEMPORARY 2010’s CENTURIES/ fall out boy 24K MAGIC/ bruno mars CHAINED TO THE RHYTHM/ katy perry ADDICTED TO A MEMORY/ zedd CHANDELIER/ sia ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME/ coldplay CHEAP THRILLS/ sia & sean paul AFTERGLOW/ ed sheeran CHEERLEADER/ omi AIN’T IT FUN/ paramore CIRCLES/ post malone AIRPLANES/ b.o.b w/haley williams CLASSIC/ mkto ALIVE/ krewella CLOSER/ chainsmokers ALL ABOUT THAT BASS/ meghan trainor CLUB CAN’T HANDLE ME/ flo rida ALL ABOUT THAT BASS/ postmodern jukebox COME GET IT BAE/ pharrell williams ALL I NEED/ awol nation COOLER THAN ME/ mike posner ALL I ASK/ adele COOL KIDS/ echosmith ALL OF ME/ john legend COUNTING STARS/ one republic ALL THE WAY/ timeflies CRAZY/ kat dahlia ALWAYS REMEMBER US THIS WAY/ lady gaga CRUISE REMIX/ florida georgia line & nelly A MILLION DREAMS/ greatest showman DANGEROUS/ guetta & martin AM I WRONG/ nico & vinz DAYLIGHT/ maroon 5 ANIMALS/ maroon 5 DEAR FUTURE HUSBAND/ meghan trainor ANYONE/ justin bieber DELICATE/ taylor swift APPLAUSE/ lady gaga DIAMONDS/ sam smith A THOUSAND YEARS/ christina perri DIE WITH YOU/ beyonce BABY/ justin bieber DIE YOUNG/ kesha BAD BLOOD/ taylor swift DOMINO/ jessie j BAD GUY/ billie eilish DON’T LET ME DOWN/ chainsmokers BANG BANG/ jessie j and ariana grande DON’T START NOW/ dua lipa BEFORE I LET GO/ beyonce DON’T STOP THE PARTY/ pitbull BENEATH YOUR BEAUTIFUL/ labrinth DRINK YOU AWAY/ justin timberlake BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE/ chris brown DRIVE BY/ train BEST DAY OF MY LIFE/ american authors DRIVERS LICENSE/ olivia rodrigo BEST SONG EVER/ one direction -

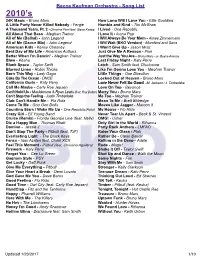

BKO Song List

Becca Kaufman Orchestra - Song List 2010’s 24K Magic - Bruno Mars How Long Will I Love You - Ellie Goulding A Little Party Never Killed Nobody - Fergie Humble and Kind - Tim McGraw A Thousand Years, Pt. 2 - Christina Perri feat. Steve Kazee I Lived - One Republic All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor I Love It - Icona Pop All of Me (Ballad) - John Legend I Will Always Be Your Mom - Aimee Zimmermann All of Me (Dance Mix) - John Legend I Will Wait (BKO Version) - Mumford and Sons American Kids - Kenny Chesney I Won't Give Up - Jason Mraz Best Day of My Life - American Authors Just Give Me A Reason - Pink Better When I'm Dancin’ - Meghan Trainor Just the Way You Are - Bruno Mars - or- Boyce Avenue Blow - Kesha Last Friday Night - Katy Perry Blank Space - Taylor Swift Latch - Sam Smith feat. Disclosure Blurred Lines - Robin Thicke Like I'm Gonna Lose You - Meghan Trainor Born This Way - Lady Gaga Little Things - One Direction Cake By The Ocean - DNCE Locked Out of Heaven - Bruno Mars California Gurls - Katy Perry Love Never Felt So Good - M. Jackson / J. Timberlake Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepsen Love On Top - Beyoncé Can't Hold Us - Macklemore & Ryan Lewis (feat. Ray Dalton) Marry You - Bruno Mars Can’t Stop the Feeling - Justin Timberlake Me Too - Meghan Trainor Club Can’t Handle Me - Flo Rida Mean To Me - Brett Eldredge Come To Me - Goo Goo Dolls Moves Like Jagger - Maroon 5 Counting Stars / Wake Me Up - One Republic/Avicii My House - Flo Rida Crazy Girl - Eli Young Band Never Tear Us Apart - Beck & St.