Tapuae, New Plymouth Marine Reserve Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oakura July 2003

he akura essenger This month JULY 2003 Coastal Schools’ Education Development Group Pictures on page 13 The Minister of Education, Trevor Mallard, has signalled a review of schooling, to include Pungarehu, Warea, Newell, Okato Primary, Okato College, Oakura and Omata schools. The reference group of representatives from the area has been selected to oversee the process and represent the community’s perspective. Each school has 2 representatives and a Principal rep from the Primary and Secondary sector. Other representatives include, iwi, early childhood education, NZEI, PPTA, local politicians, Federated Farmers, School’s Trustee Association and the Ministry of Education in the form of a project manager. In general the objectives of the reference group are to be a forum for discussion of is- sues with the project manager. There will be plenty of opportunity for the local com- Card from the Queen for munities to have input. Sam and Tess Dobbin Page 22 The timeframe is to have an initial suggestion from the Project Manager by September 2003. Consultation will follow until December with a preliminary announcement from the Ministry of Education in January 2004. Further consultation will follow with the Minister’s final announcement likely in June 2004. This will allow for any develop- ment needed to be carried out by the start of the 2005 school year. The positive outcome from a review is that we continue to offer quality education for Which way is up? the children of our communities for the next 10 to 15 years as the demographics of our communities are changing. Nick Barrett, Omata B.O.T Chairperson Page 5 Our very own Pukekura Local artist “Pacifica of Land on Sea” Park? Page 11 exhibits in Florence Local artist Caz Novak has been invited to exhibit at the Interna- tional Biennale of Contemporary Art in Florence this year. -

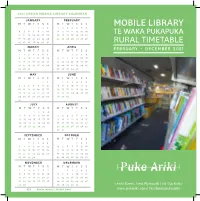

Mobile Library

2021 URBAN MOBILE LIBRARY CALENDAR JANUARY FEBRUARY M T W T F S S M T W T F S S MOBILE LIBRARY 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 TE WAKA PUKAPUKA 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 RURAL TIMETABLE MARCH APRIL M T W T F S S M T W T F S S FEBRUARY - DECEMBER 2021 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 MAY JUNE M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 31 JULY AUGUST M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 1 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 SEPTEMBER OCTOBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 NOVEMBER DECEMBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 1 Ariki Street, New Plymouth | 06-759 6060 KEY RURAL MOBILE LIBRARY DAYS www.pukariki.com | facebook/pukeariki Tuesday Feb 9, 23 Mar 9, 23 April 6 May 4, 18 TE WAKA PUKAPUKA June 1, 15, 29 July 27 Aug 10, 24 Sept 7, 21 Oct 19 Nov 2, 16, 30 Dec 14 Waitoriki School 9:30am – 10:15am Norfolk School 10:30am – 11:30am FEBRUARY - DECEMBER 2021 Ratapiko School 11:45am – 12:30pm Kaimata School 1:30pm – 2:30pm The Mobile Library/Te Waka Pukapuka stops at a street near you every second week. -

New Plymouth Ports Guide

PORT GUIDE Last updated: 24th September 2015 FISYS id : PO5702 UNCTAD Locode : NZ NPL New Plymouth, NEW ZEALAND Lat : 39° 03’ S Long : 174° 02’E Time Zone: GMT. +12 Summer time kept as per NZ regulations Max Draught: 12.5m subject to tide Alternative Port Name: Port Taranaki Vessels facilities [ x ] Multi-purpose [ x ] Break-bulk [ x ] Pure container [ x ] Dry bulk [ x ] Liquid (petro-chem) [ x ] Gas [ x ] Ro-ro [ x ] Passenger/cruise Authority/Co name: Port Taranaki Ltd Address : Port Taranaki Ltd PO Box 348 New Plymouth North Island New Zealand Telephone : +64 6 751 0200 Fax : +64 6 751 0886 Email: [email protected] Key Personnel Position Email Guy Roper Chief Executive [email protected] Capt Neil Marine Services Manager / [email protected] Armitage Harbour Master 1 SECTION CONTENTS Page 2.0 Port Description 2.1 Location. 3 2.2 General Overview. 3 2.3 Maximum Size 3 3.0 Pre Arrival Information. 3.1 ETA’s 4 3.2 Documentation. 4 3.3 Radio. 5 3.4 Health. 5 3.5 Customs and Immigration. 5 3.6 Standard Messages. 7 3.7 Flags. 7 3.8 Regulations and General Notices. 7 3.9 Agencies 9 4.0 Navigation. 4.1 Port Limits. 9 4.2 Sea buoys, Fairways and Channels. 9 4.3 Pilot. 9 4.4 Anchorage’s. 10 4.5 Tides. 10 4.6 Dock Density. 10 4.7 Weather 10 4.8 VHF. 11 4.9 Navigation 11 4.10 Charts and Publications. 13 4.11 Traffic Schemes. 13 4.12 Restrictions. -

MA10: Museums – Who Needs Them? Articulating Our Relevance and Value in Changing and Challenging Times

MA10: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? Articulating our relevance and value in changing and challenging times HOST ORGANISATIONS MAJOR SPONSORS MA10: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? Articulating our relevance and value in changing and challenging times WEDNESDAY 14 – FRIDAY 16 APRIL, 2010 HOSTED BY PUKE ARIKI AND GOVETt-BREWSTER ART GALLERY VENUE: TSB SHOWPLACE, NEW PLYMOUTH THEME: MUSEUMS – WHO NEEDS THEM? MA10 will focus on four broad themes that will be addressed by leading international and national keynote speakers, workshops and case studies: Social impact and creative capital: what is the social relevance and contribution of museums and galleries within a broader framework? Community engagement: how do we undertake audience development, motivate stakeholders as advocates, and activate funders? Economic impact and cultural tourism: how do we demonstrate our economic value and contribution, and how do we develop economic collaborations? Current climate: how do we meet these challenges in the current economic climate, the changing political landscape nationally and locally, and mediate changing public and visitor expectations? INTERNATIONAL SPEAKERS INCLUDE MUSEUMS AOTEAROA Tony Ellwood Director, Queensland Art Gallery & Gallery of Modern Art Museums Aotearoa is New Zealand’s Elaine Heumann Gurian Museum Advisor and Consultant independent professional peak body for museums and those who work Michael Houlihan Director General, Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales in or have an interest in museums. Chief Executive designate, Te Papa Members include museums, public art galleries, historical societies, Michael Huxley Manager of Finance, Museums & Galleries NSW science centres, people who work within these institutions and NATIONAL SPEAKERS INCLUDE individuals connected or associated Barbara McKerrow Chief Executive Officer, New Plymouth District Council with arts, culture and heritage in New Zealand. -

TSB COMMUNITY TRUST REPORT 2016 SPREAD FINAL.Indd

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CHAIR’S REPORT Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa Greetings, greetings, greetings to you all The past 12 months have been highly ac ve for the Trust, As part of the Trust’s evolu on, on 1 April 2015, a new Group marked by signifi cant strategic developments, opera onal asset structure was introduced, to sustain and grow the improvements, and the strengthening of our asset base. Trust’s assets for future genera ons. This provides the Trust All laying stronger founda ons to support the success of with a diversifi ca on of assets, and in future years, access to Taranaki, now and in the future. greater dividends. This year the Trust adopted a new Strategic Overview, As well as all this strategic ac vity this year we have including a new Vision: con nued our community funding and investment, and To be a champion of posi ve opportuni es and an agent of have made a strong commitment to the success of Taranaki benefi cial change for Taranaki and its people now and in communi es, with $8,672,374 paid out towards a broad the future range of ac vi es, with a further $2,640,143 commi ed and yet to be paid. Our new Vision will guide the Trust as we ac vely work with others to champion posi ve opportuni es and benefi cial Since 1988 the Trust has contributed over $107.9 million change in the region. Moving forward the Trust’s strategic dollars, a level of funding possible due to the con nued priority will be Child and Youth Wellbeing, with a focus on success of the TSB Bank Ltd. -

State of the Arts

Te Tohu a Toi STATE OF THE ARTS South Taranaki Arts Bulletin # 43 Autumn 2021 | Art News | Opportunities | Exhibitions | Art Events | The Everybody’s Theatre Centennial Celebrations were held in February It’s been awesome to see the transformation and journey of this historic Ōpunakē facility over recent years by the dedicated trustees, community, collaborators and funders. While many groups and towns would be daunted and overwhelmed by challenges such as earthquake strengthening and major refurbishment, the cheerleaders for Everybody’s Theatre have triumphed through hard work and commitment to the cause. The celebration included free movie screenings, lots of dress-ups, live jazz music and dancing. A new centennial book has been compiled by Maree Drought and Debbie Campbell, showing an in-depth look at the changing face of the Theatre building since 1910. The Theatre hosts special events and runs a monthly Boutique Night, as well as showing new movies on the Coast. Well done to all involved, your achievements are inspirational. Everybody’s Theatre Trustees celebrate 100 years I recently had the pleasure of attending the Hāwera Repertory production of Bugsy Malone at another impressive and very well equipped South Taranaki facility, Hāwera Memorial Theatre. I was blown away by the outstanding talent on show by the youth actors, dancers and band, as well as the seamless production, sets and lighting. If you’ve ever wanted to be a part of the live theatre experience, I encourage you to get involved and join a local group. Accessibility to arts and creativity is essential for everyone in Aotearoa. -

Sugar Loaf Islands Marine Protected Area Act 1991

Reprint as at 1 July 2013 Sugar Loaf Islands Marine Protected Area Act 1991 Public Act 1991 No 8 Date of assent 21 March 1991 Commencement 21 March 1991 Contents Page Title 2 1 Short Title 2 2 Interpretation 2 3 Purpose of Act 4 4 Principles 4 5 Prohibition on mining 4 6 Effect of Act on Fisheries Act 1983 4 6A Consents relating to New Plymouth Power Station 5 7 Protected Area to be conservation area 5 8 Protected Area may be marked 5 9 Rights of access and navigation 6 10 Offences 6 10A Control of dogs 7 11 Transitional provisions relating to existing petroleum 7 prospecting licence Note Changes authorised by section 17C of the Acts and Regulations Publication Act 1989 have been made in this reprint. A general outline of these changes is set out in the notes at the end of this reprint, together with other explanatory material about this reprint. This Act is administered by the Department of Conservation. 1 Sugar Loaf Islands Marine Protected Reprinted as at Area Act 1991 1 July 2013 12 Consequential amendment to Conservation Act 1987 8 An Act to provide for the setting up and management of the Sugar Loaf Islands Marine Protected Area for the purpose of protecting that area of the sea and foreshore in its natural state as the habitat of marine life, and to provide for the enhancement of recreational activities 1 Short Title This Act may be cited as the Sugar Loaf Islands Marine Pro- tected Area Act 1991. 2 Interpretation In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,— Director-General means the Director-General of Conserva- tion -

Oakura August 2018

OAKURA AUGUST ‘18 Farewell to a much loved and admired principal at Spotswood College Affordable Luxury is closer OAKURA 1 than you think. CALL TODAY | 0508 562 284 | LOCATIONHOMES.CO.NZ Move It or Lose It - fitness classes: Oakura Hall, Wednesdays & Fridays, 9.30am, Contact Gloria 752 7442. Oakura Bowling and Social Club: Bowling tournaments begin September through to April with both mid-week and weekend games. For information contact Steve Muller on 06 757 4399. OAKURA Oakura Meditation Group: - Mondays 8.10pm 37a TOM Oakura is a free monthly publication, delivered Donnelly St, ph 0272037215, email [email protected] at the beginning of each month to all homes from New Plymouth city limits to Okato. Oakura Playcentre: 14 Donnelly St, Oakura. Sessions Do you have a story of local interest that you’d like to run Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays 9am-noon during share with the readers of TOM? Phone 0800 THE TOM school terms. Visitors welcome. Ph Kate Garner on 021- or visit thetom.co.nz 254 4769. Co-ordinator/Features/Advertising/Lay up Oakura Pony Club: Contact Marlies Butland Delfos Kim Ferens ph 0274595962. email: [email protected] 0800 843 866 Oakura Pool Club: Meets every Wednesday evening 7pm 027 4126117 at Butlers Reef over winter. Points of view expressed in contributed articles are not Phone Sheree 027 3444 723. necessarily the views of The TOM Oakura Yoga: - Shine Yoga Studio, 37a Donnelly St, Dates to remember for June 2018 issue. Copy & Ads - www.shineyoga.co.nz for days and times, ph 0272037215. Oakura23 May. -

The Social History of Taranaki 1840-2010 Puke Ariki New Zealand

Date : 07/06/2006 Common Ground: the social history of Taranaki 1840-2010 Bill Mcnaught Puke Ariki New Zealand Meeting: 153 Genealogy and Local History Simultaneous Interpretation: No WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS: 72ND IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL 20-24 August 2006, Seoul, Korea http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla72/index.htm Abstract: Puke Ariki opened in 2003 and is the flagship museum, library and archival institution for Taranaki. Some commentators have suggested that there is no region in New Zealand with a richer heritage than Taranaki, but some episodes were among the most difficult in New Zealand’s history. There is a growing view that New Zealand needs to talk about some of its difficult history before it can heal the wounds that are still apparent in society. ‘Common Ground’ is a ground-breaking 5 year programme that begins in 2006 to look at the social history of Taranaki including some of the painful chapters. This paper explains some of the background and ways of joint working across library, museum and archival professions at Puke Ariki. Puke Ariki (pronounced ‘poo kay ah ree kee’ with equal emphasis on each syllable) means ‘Hill of Chiefs’ in the Māori language. Before Europeans arrived it was a fortified Māori settlement - also a sacred site because the bones of many chiefs are said to have been interred there. When the British settlers founded the small city of New Plymouth in the 19th century they removed the hill and used the soil as the foundation material for industrial building. Today it is the location for the flagship Taranaki museum, library and archival institution. -

SURF HIGHWAY 45 Your Guide to the Touring Route Around Taranaki’S Coastline

SURF HIGHWAY 45 Your guide to the touring route around Taranaki’s coastline taranaki.co.nz/visit WELCOME TO THE SURF HIGHWAY Surf Highway 45 is the 105km coastal route connecting New Plymouth (1) in the north to Hāwera (2) in the south. Between these centres there are dozens of notable places to stop, from surf breaks, beaches, points of historic and cultural interest, scenic spots, and cafés in vibrant and welcoming villages. A journey along the Surf Highway traces the route of generations of surfers, but it offers much more than just surf. The highway weaves through a number of Taranaki’s stories – the surf, the landscape, the rich history, and the creativity, all the while under the watchful gaze of Taranaki Maunga. For more information head to taranaki.co.nz/visit RICH IN HISTORY Taranaki’s history begins with our picture-perfect ancestor Taranaki Maunga and his mythical journey from the Central Plateau (brokenhearted after losing a battle for Mount Pihanga) and includes historic land battles, the birth of the passive resistance movement, and pioneering industrial growth, all of which have contributed to modern-day Taranaki and the many vivid stories we have to tell. These stories are best experienced through the many museums on offer, with the following located on or near Surf Highway 45. • New Plymouth’s waterfront Puke Ariki (1) is a museum, library and i-SITE providing information about the city’s past and present. A fascinating guided walk is also available – book at the i-SITE, 1 Ariki St, New Plymouth. • Tawhiti Museum and Traders & Whalers (3) has been repeatedly judged one of the country’s best museums, and has to be experienced to be believed. -

Will You Survive the Next Eruption? Before The

AN EXHIBITION EXPLORING A HYPOTHETICAL ERUPTION OF MT. TARANAKI WILL YOU SURVIVE THE NEXT ERUPTION? Mount Taranaki or Mount Egmont is a The last major eruption of Taranaki occurred stratovolcano of alternating layers of lava around 1755, and it is estimated that the flows and ash deposits. It stands at 2,518m volcano has erupted over 160 times in the last in Egmont National Park and is the second 36,000 years. There are no indications that highest mountain in the North Island. It Mt. Taranaki is about to erupt, however, its is the dominant landmark towering over a unbroken geological history of activity tells us district of fertile, pastoral land with a bounty it will in the future. of resources ranging from oil to iron-sand to Mt. Taranaki is well monitored by the groundwater. GeoNet project, and dormant volcanoes like Mt. Taranaki is part of a volcanic chain that Taranaki almost always demonstrate unrest includes the Kaitake and Pouakai Ranges, before an eruption starts, with warning Paritutu, and the Sugar Loaf islands. periods likely to range between days to months. BEFORE THE ERUPTION Find out about the volcanic risk in your community. Ask your local council about emergency plans and how they will warn you of a volcanic eruption. ICAO AVIATION VOLCANO NEW ZEALAND VOLCANIC ALERT LEVEL SYSTEM COLOUR CODE Volcanic Alert Level Volcanic Activity Most Likely Hazards Volcano is in normal, non- Major volcanic eruption Eruption hazards on and beyond volcano* eruptive state or, a change 5 from a higher alert level: Moderate volcanic eruption Eruption hazards on and near volcano* GREEN Volcanic activity is considered 4 to have ceased, and volcano reverted to its normal, non- ERUPTION 3 Minor volcanic eruption Eruption hazards on and near vent* eruptive state. -

New Plymouth District a Guide for New Settlers Haere Mai! Welcome!

Welcome to New Plymouth District A guide for new settlers Haere Mai! Welcome! Welcome to New Plymouth District This guide is intended for people who have recently moved to New Plymouth District. We hope it will be helpful during your early months here. We're here for you Contact us for free, confidential information and advice Call: 06 758 9542 or 0800 FOR CAB (0800 367 222) EMAIL or ONLINE CHAT: www.cab.org.nz Nga Pou Whakawhirinaki o Aotearoa You can also visit us at Community House (next to the YMCA) on 32 Leach Street. The guide is also available on the following websites: www.newplymouthnz.com/AGuideForNewSettlers www.cab.org.nz/location/cab-new-plymouth Disclaimer: Although every care has been taken in compiling this guide we accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, or the results of any actions taken on the basis of any information contained in this publication. Last updated: August 2020 Table of contents Page 1. Introducing New Plymouth District Message of welcome from the Mayor of New Plymouth ..................... 1 New Plymouth - past and present ......................................................... 2 Tangata whenua ...................................................................................... 3 Mt Taranaki .............................................................................................. 3 Climate and weather ............................................................................... 4 2. Important first things to do Getting information ...............................................................................