Jay Weldon Wilkey-Certain Aspects Oj Form Zn the Vocal Music Oj Alban Berg Ann Arbor: University Microfilms (UM Order No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Saxophone Symposium: an Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 The aS xophone Symposium: An Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014 Ashley Kelly Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Ashley, "The aS xophone Symposium: An Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2819. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2819 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SAXOPHONE SYMPOSIUM: AN INDEX OF THE JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN SAXOPHONE ALLIANCE, 1976-2014 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and AgrIcultural and MechanIcal College in partIal fulfIllment of the requIrements for the degree of Doctor of MusIcal Arts in The College of MusIc and DramatIc Arts by Ashley DenIse Kelly B.M., UniversIty of Montevallo, 2008 M.M., UniversIty of New Mexico, 2011 August 2015 To my sIster, AprIl. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sIncerest thanks go to my committee members for theIr encouragement and support throughout the course of my research. Dr. GrIffIn Campbell, Dr. Blake Howe, Professor Deborah Chodacki and Dr. Michelynn McKnight, your tIme and efforts have been invaluable to my success. The completIon of thIs project could not have come to pass had It not been for the assIstance of my peers here at LouIsIana State UnIversIty. -

Proquest Dissertations

The saxophone in Germany, 1924-1935 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bell, Daniel Michaels Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 07:49:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290020 THE SAXOPHONE IN GERMANY 1924-1935 by Daniel Michaels Bell Copyright © Daniel Michaels Bell 2004 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3131585 Copyright 2004 by Bell, Daniel Michaels All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3131585 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. -

The Deutscher Turnerbund and the Berg Violin Concerto

“Frisch, Fromm, Fröhlich, Frei.” The Deutscher Turnerbund and the Berg Violin Concerto Douglas Jarman All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 27/01/2016 Accepted: 20/07/2016 Published: 17/02/2017 Last updated: 17/02/2017 How to cite: Douglas Jarman, ““Frisch, Fromm, Fröhlich, Frei.” The Deutscher Turnerbund and the Berg Violin Concerto,” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies (February 17, 2017) Tags: 20th century; Atonality; Berg, Alban; Retrogrades; Second Viennese School; Violin concerto I am deeply grateful to Regina Busch, my colleague in the preparation of the edition of the Violin Concerto in Alban Berg, Sämtliche Werke, whose constructive criticism and deep knowledge of the sources have helped me so much in the writing of this article. Abstract Although Berg himself made public the nature of the extra-musical stimulus behind the composition of the Violin Concerto, through both his dedication “Dem Andenken eines Engels” and the article published by his biographer Willi Reich, the sketches for the work show that he originally planned to base the work on the motto of the Deutscher Turnerbund. Since the Turnerbund had strong links with the NSDAP and was banned in Austria in 1935 when the Violin Concerto was written, Berg’s intention to use the motto raises questions about his attitude toward and relationship with Nazi cultural policy and his efforts to survive as an artist in the mid-1930s. The article proposes a possible explanation based on Berg’s consistent use of retrogrades and palindromes in his other works as symbols of denial and negation. -

46Th SEASON PROGRAM NOTES

th SEASON PROGRAM NOTES 46 Week 5 August 12 – 18, 2018 Sunday, August 12, 6 pm very few dynamic indications (Mozart was Composed in memory of Popper’s publisher apparently content to leave such decisions Daniel Rahter, the Requiem projects an WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART to his performers), but the movement does appropriately somber and consoling mood. (1756 – 1791) close quietly on the dotted figure that The brief piece is distinctive for the rich Sonata in B-flat Major for Bassoon & Cello, has figured prominently throughout. The sonority of the three solo cellos, and in its K. 292 (1775) Andante, in F Major, offers long singing serious and dark sound the Requiem is often lines for the bassoon; the movement is in reminiscent of the music of Popper’s friend When Mozart and his father visited Munich binary form, and Mozart offers the option to Johannes Brahms. The Requiem opens with in the first months of 1775 for the premiere repeat both halves. The concluding Allegro the three cellos alone, laying out the dotted of the boy’s opera buffa La finta giardiniera, is a cheerful rondo based on the bassoon’s main idea, which soon passes among the they found themselves the toast of the city’s energetic opening tune. This Sonata is never three soloists. While it rises to a full-throated musical life. The opera was a success, they really difficult (Mozart was aware that he climax, this is not extroverted or virtuosic conducted concerts, and were invited to was writing for amateur musicians), but music. It remains lyric and expressive masked balls, and there was much attention this is certainly the most extroverted of throughout, and Popper constantly reminds paid to the talents of Wolfgang, who turned the movements—full of trills, syncopated his performers: dolce, espressivo, and 19 while he was in Munich. -

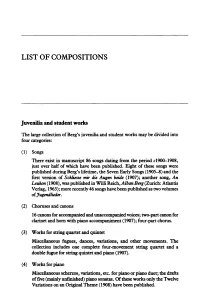

List of Compositions

LIST OF COMPOSITIONS Juvenilia and student works The large collection of Berg's juvenilia and student works may be divided into four categories: (1) Songs There exist in manuscript 86 songs dating from the period c1900-1908, just over half of which have been published. Eight of these songs were published during Berg'S lifetime, the Seven Early Songs (1905-8) and the ftrst version of Schliesse mir die Augen beide (1907); another song, An Leukon (1908), was published in Willi Reich, Alban Berg (Zurich: Atlantis Verlag, 1963); more recently 46 songs have been published as two volumes ofJugendlieder. (2) Choruses and canons 16 canons for accompanied and unaccompanied voices; two-part canon for clarinet and hom with piano accompaniment (1907); four-part chorus. (3) Works for string quartet and quintet Miscellaneous fugues, dances, variations, and other movements. The collection includes one. complete four-movement string quartet and a double fugue for string quintet and piano (1907). (4) Works for piano Miscellaneous scherzos, variations, etc. for piano or piano duet; the drafts of ftve (mainly unfmished) piano sonatas. Of these works only the Twelve Variations on an Original Theme (1908) have been published. 292 THE BERG COMPANION All of the unpublished works should appear in the near future as part of the forthcoming Alb~ Berg Gesamtmugabe. Published works Jugendlieder, vol. 1(1901-4),23 selected songs for voice and piano Schliesse mir die Augen beide [1], for voice and piano (1907) Jugendlieder, vol. 2 (1904-8), 23 selected songs for voice and piano Seven Early Songs, for voice and piano (1905-8); orchestral arrangement (1928) Am Leukon, for voice and piano (1908) Twelve Variations on an Original Theme, for piano (1908) Sonata op. -

Cognitive Structure in Viennese Twelve-Tone Rows

Tonal and “Anti-Tonal” Cognitive Structure in Viennese Twelve-Tone Rows PAUL T. von HIPPEL [1] University of Texas, Austin DAVID HURON Ohio State University ABSTRACT: We show that the twelve-tone rows of Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern are “anti-tonal”—that is, structured to avoid or undermine listener’s tonal schemata. Compared to randomly generated rows, segments from Schoenberg’s and Webern’s rows have significantly lower fit to major and minor key profiles. The anti-tonal structure of Schoenberg’s and Webern’s rows is still evident when we statistically controlled for their preference for other row features such as mirror symmetry, derived and hexachordal structures, and preferences for certain intervals and trichords. The twelve-tone composer Alban Berg, by contrast, often wrote rows with segments that fit major or minor keys quite well. Submitted 2020 May 4; accepted 2020 June 2 Published 2020 October 22; https://doi.org/10.18061/emr.v15i1-2.7655 KEYWORDS: serialism, twelve-tone music, music cognition, tonality, tonal schema, contratonal INTRODUCTION NEARLY 100 years ago, in 1921, the Viennese composer Arnold Schoenberg developed a “method of composing with twelve tones” (Schoenberg, 1941/1950). Schoenberg’s approach began with a twelve-tone row, which assigned an order to the twelve tones of the chromatic scale. Because each “tone” could be used in any octave, it was actually what would later be called a “chroma” in psychology, or a “pitch class” in music theory. The tone row provided the basis for all of a composition’s harmonic and melodic material. In addition to using the tone row in its original, basic, or prime form, a composer could use the tone row in three derived forms: retrograde, which turned the tone row backward; inversion, which turned the tone row upside- down by inverting all its intervals; or retrograde inversion, which did both.[2] In addition, any form of the row could be transposed by moving every chroma up (or down[3]) by 1 to 11 semitones. -

Culture and History in the Performance of Diegetic Music In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Auf der Bühne: Culture and History in the Performance of Diegetic Music in German Opera A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Geoffrey Nicholas Gardiner Pope 2017 © Copyright by Geoffrey Nicholas Gardiner Pope 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Auf der Bühne: Culture and History in the Performance of Diegetic Music in German Opera by Geoffrey Nicholas Gardiner Pope Doctor of Musical Arts in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Neal H. Stulberg, Chair In this dissertation, I examine the role and evolution of diegetic music as represented in the Bühnenmusik of four pivotal operas: Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (1865); Alban Berg’s Wozzeck (1924) and Lulu (1935); and Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten (1965). These operas were chosen not simply for their shared Teutonic origins, but because they are important parts of an ideological and aesthetic lineage that clearly shows how the relationship between music and drama was transformed through the use of Bühnenmusik. In addition to exploring the musical materials and meanings of diegetic music within these operas, I address the challenges and peculiarities of conducting Bühnenmusik, and the role that evolving technology has played in overcoming issues of coordination between the stage and the orchestra pit. ii The dissertation of Geoffrey Nicholas Gardiner Pope is approved. Robert S. Winter Michael E. Dean Michael S.Y. Chwe Neal H. Stulberg, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2017 iii To my wife Lizzy, who is everything to me. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Auf der Bühne: Culture and History in the Performance of Diegetic Music in German Opera Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6627d0ch Author Pope, Geoffrey Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Auf der Bühne: Culture and History in the Performance of Diegetic Music in German Opera A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Geoffrey Nicholas Gardiner Pope 2017 © Copyright by Geoffrey Nicholas Gardiner Pope 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Auf der Bühne: Culture and History in the Performance of Diegetic Music in German Opera by Geoffrey Nicholas Gardiner Pope Doctor of Musical Arts in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Neal H. Stulberg, Chair In this dissertation, I examine the role and evolution of diegetic music as represented in the Bühnenmusik of four pivotal operas: Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (1865); Alban Berg’s Wozzeck (1924) and Lulu (1935); and Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten (1965). These operas were chosen not simply for their shared Teutonic origins, but because they are important parts of an ideological and aesthetic lineage that clearly shows how the relationship between music and drama was transformed through the use of Bühnenmusik. In addition to exploring the musical materials and meanings of diegetic music within these operas, I address the challenges and peculiarities of conducting Bühnenmusik, and the role that evolving technology has played in overcoming issues of coordination between the stage and the orchestra pit. -

Alban Berg and Peter Altenberg: Intimate Art and the Aesthetics of Life Author(S): David P

Alban Berg and Peter Altenberg: Intimate Art and the Aesthetics of Life Author(s): David P. Schroeder Source: Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Summer, 1993), pp. 261-294 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/831967 Accessed: 29-06-2016 15:38 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/831967?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Musicological Society, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Musicological Society This content downloaded from 129.173.74.41 on Wed, 29 Jun 2016 15:38:10 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Alban Berg and Peter Altenberg: Intimate Art and the Aesthetics of Life* BY DAVID P. SCHROEDER UR FASCINATION with Alban Berg's music has resulted in a peculiarly unbalanced view of this complex composer, and Berg himself has been an accomplice to the distortion. -

The Deutscher Turnerbund and the Berg Violin Concerto

“Frisch, Fromm, Fröhlich, Frei.” The Deutscher Turnerbund and the Berg Violin Concerto Douglas Jarman All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 27/01/2016 Accepted: 20/07/2016 Published: 17/02/2017 Last updated: 17/02/2017 How to cite: Douglas Jarman, ““Frisch, Fromm, Fröhlich, Frei.” The Deutscher Turnerbund and the Berg Violin Concerto,” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies (February 17, 2017) Tags: 20th century; Atonality; Berg, Alban; Retrogrades; Second Viennese School; Violin concerto I am deeply grateful to Regina Busch, my colleague in the preparation of the edition of the Violin Concerto in Alban Berg, Sämtliche Werke, whose constructive criticism and deep knowledge of the sources have helped me so much in the writing of this article. Abstract Although Berg himself made public the nature of the extra-musical stimulus behind the composition of the Violin Concerto, through both his dedication “Dem Andenken eines Engels” and the article published by his biographer Willi Reich, the sketches for the work show that he originally planned to base the work on the motto of the Deutscher Turnerbund. Since the Turnerbund had strong links with the NSDAP and was banned in Austria in 1935 when the Violin Concerto was written, Berg’s intention to use the motto raises questions about his attitude toward and relationship with Nazi cultural policy and his efforts to survive as an artist in the mid-1930s. The article proposes a possible explanation based on Berg’s consistent use of retrogrades and palindromes in his other works as symbols of denial and negation. -

Dramaturgical Aspects of Metaphysical Temporality in the Libretti of Alban Berg’S Operas

“A soul, rubbing the sleep from its eyes in the next world”: Dramaturgical Aspects of Metaphysical Temporality in the Libretti of Alban Berg’s Operas Vanja Ljubibratić All content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Received: 21/04/2019 Accepted: 21/08/2019 Institution (Vanja Ljubibratić): University of Turku Published: 17/09/2019 Last updated: 17/09/2019 How to cite: Vanja Ljubibratić, ““A soul, rubbing the sleep from its eyes in the next world”: Dramaturgical Aspects of Metaphysical Temporality in the Libretti of Alban Berg’s Operas,” Musicologica Austriaca: Journal for Austrian Music Studies (September 17, 2019) Tags: 20th century; Alban Berg; German Opera; Libretti; Libretto studies; Metaphysics; Philosophy; Temporality; Wagner, Richard Abstract Temporality, as a narrative device, was a central element in Alban Berg’s operas both textually and musically. The systematic form of creating circular structures with palindromes via large- scale retrogrades was meant to turn narrative time back onto itself as an expression of fatalistic negation. This conceptualization held metaphysical implications for Berg that coalesced with his notions of time and space. In his operas, and among other ploys, Berg would appropriate the libretti to textually traverse between the two temporal realms of the empirical world and the metaphysical plane in order to obfuscate the perceptions of reality for his characters, and ultimately put them on paths of predetermined doom through a perpetual repetition of fate, as in the case of Wozzeck. Berg would do this at his own discretion, superseding the authority of the playwrights whose texts he chose to set to music, in order to achieve his desired philosophical and autobiographical outcomes, which were his primary concerns. -

Alban Berg's Sieben Frühe Lieder

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 6-16-2014 Alban Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder: An Analysis of Musical Structures and Selected Performances Lisa A. Lynch University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Lynch, Lisa A., "Alban Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder: An Analysis of Musical Structures and Selected Performances" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 480. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/480 Alban Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder: An Analysis of Musical Structures and Selected Performances Lisa Anne Lynch, DMA University of Connecticut, 2014 ABSTRACT Alban Berg’s Sieben frühe Lieder, composed between 1905-08, lie on the border between late 19th-century Romanticism and early atonality, resulting in their particularly lyrical and yet distinctly modern character. This dissertation looks in detail at the songs with an emphasis on the relevance of a musical analysis to performers. Part I provides an overview of the historical context surrounding the Sieben frühe Lieder, including Berg’s studies with Schoenberg, stylistic features, biographical details, and analytic approaches to Berg’s work. The primary focus of the dissertation, Part II, is a study of each individual song. Each analysis begins with an overview of the formal design of the piece, taking into consideration the structure and content of the poetry, and includes a chart of the song’s form. A detailed study of the harmonic structure and motivic development within the song follows. The analysis also addresses the nuances of text setting. Following each analysis of musical structure, specific aspects of performance are discussed, including comparisons of recordings and the expressive effects of different performers’ choices.