Krakow's Foundation Myth: an Indo-European Theme Through The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

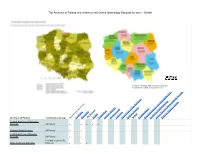

The Archives of Poland and Where to Find Online Genealogy Records for Each - Sheet1

The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Archives of Poland Territorial coverage Search theGenBaza ArchivesGenetekaJRI-PolandAGAD Przodek.plGesher Archeion.netGalicia LubgensGenealogyPoznan in the BaSIAProject ArchivesPomGenBaseSzpejankowskisPodlaskaUpper and Digital Szpejenkowski SilesianSilesian Library Genealogical Digital Library Society Central Archives of Historical Records All Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ National Digital Archive All Poland ✓ ✓ Central Archives of Modern Records All Poland ✓ ✓ Podlaskie (primarily), State Archive in Bialystok Masovia ✓ ✓ ✓ The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 Branch in Lomza Podlaskie ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Pomerania State Archive in Bydgoszcz and Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Greater Branch in Inowrocław Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), Świetokrzyskie, Łódz, National Archives in Częstochowa and Opole ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Pomerania (primarily), State Archive in Elbląg with the Warmia-Masuria, Seat in Malbork Kuyavian-Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gdansk Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Gdynia Branch Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gorzow Lubusz (primarily), Wielkopolski Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ Greater Poland (primarily), Łódz, State Archive in Kalisz Lower Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), State Archive in Katowice Lesser Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Bielsko-Biala Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Cieszyn Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

Gniezno (Gmina Wiejska)

GMINA WIEJSKA GNIEZNO 32:,$7*1,(ħ1,(ē6., PLHMVFRZRĞFL 37 Liczba 2019 VRáHFWZ 30 /8'12ĝû Powierzchnia w km² 178 /XGQRĞüZHGáXJSáFLLJUXSZLHNXZ2019 r. Powiat Wybrane dane statystyczne 2017 2018 2019 2019 0ĉĩ&=<ħ1, KOBIETY 6098 6170 /XGQRĞü 11614 11951 12268 145418 /XGQRĞü na 1 km² 65 67 69 116 .RELHW\QDPĊĪF]\]Q 101 101 101 104 /XGQRĞüZZLHNXQLHSURGXNF\MQ\PQDRVyE w wieku produkcyjnym 59,9 61,2 62,1 67,2 'RFKRG\RJyáHPEXGĪHWXJPLQ\QDPLHV]NDĔFD Z]á 4538 4679 5207 5103 :\GDWNLRJyáHPEXGĪHWXJPLQ\QDPLHV]NDĔFD Z]á 5158 5427 5395 5139 Turystyczne obiekty noclegowe 2 2 2 49 0LHV]NDQLDRGGDQHGRXĪ\WNRZDQLDQDW\V OXGQRĞFL 131 158 169 57 3UDFXMąF\ QDOXGQRĞFL 114 103 96 198 8G]LDáEH]URERWQ\FK]DUHMHVWURZDQ\FK ZOLF]ELHOXGQRĞFLZZLHNXSURGXNF\MQ\P Z 2,8 2,0 1,6 2,1 /XGQRĞü–ZRJyáXOXGQRĞFL–NRU]\VWDMąFD z instalacji: ZRGRFLąJRZHM 86,5 86,5 88,2 97,3 kanalizacyjnej 27,5 27,6 20,6 75,7 gazowej 41,8 45,1 48,9 51,5 Podmioty gospodarki narodowej w rejestrze 5(*21QDW\VOXGQRĞFLZZLHNX produkcyjnym 1840 1893 1962 1867 Wybrane dane demograficzne 0LJUDFMHOXGQRĞFLQDSRE\WVWDá\ Powiat Gmina Powiat=100 w 2019 r. /XGQRĞü 145418 12268 8,4 w tym kobiety 74258 6170 8,3 8URG]HQLDĪ\ZH 1600 139 8,7 Zgony 1398 74 5,3 Przyrost naturalny 202 65 . 6DOGRPLJUDFMLRJyáHP -113 262 . /XGQRĞüZZLHNX przedprodukcyjnym 28953 2951 10,2 produkcyjnym 86950 7570 8,7 poprodukcyjnym 29515 1747 5,9 D'DQHGRW\F]ąRELHNWyZSRVLDGDMąF\FK10LZLĊFHMPLHMVFQRFOHJRZ\FK6WDQZGQLX31OLSFDE%H]SRGPLRWyZJRVSRGDUF]\FKROLF]ELHSUDFXMąF\FKGR9 osób oraz gospodarstw LQG\ZLGXDOQ\FKZUROQLFWZLHF:SU]\SDGNXPLJUDFML]DJUDQLF]Q\FKGDQHGRW\F]ą2014 r. 1 FINANSE PUBLICZNE 'RFKRG\LZ\GDWNLEXGĪHWXJPLQ\ZHGáXJURG]DMyZZU ĝURGNLZGRFKRGDFKEXGĪHWX gminy na finansowanie LZVSyáILQDQVRZDQLHSURJUDPyZ i projektów unijnych w 2019 r. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

THE POLISH RES PUBLICA of NATIONAL and ETHNIC Minorities from the PIASTS to the 20TH CENTURY

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI 2014, No. II MARCELI KOSMAN Poznań THE POLISH RES PUBLICA OF NATIONAL AND ETHNIC MINORITIES FROM THE PIASTS TO THE 20TH CENTURY Początki Polski [The Beginnings of Poland], a fundamental work by Henryk Łowmiański, is subtitled Z dziejów Słowian w I tysiącleciu n.e. [On the History of Slavs in the 1st Millennium A.D.]. Its sixth and final volume, divided into two parts, is also titled Poczatki Polski but subtitled Polityczne i społeczne procesy kształtowania się narodu do początku wieku XIV [Political and Social Processes of Nation Forma- tion till the Beginning of the 14th Century]1. The subtitle was changed because the last volume concerns the formation of the Piast state and emergence of the Polish nation. Originally, there were to be three volumes. The first volume starts as follows: The notion of the beginnings of Poland covers two issues: the genesis of the state and the genesis of the nation. The two issues are closely connected since a state is usually a product of a specific ethnic group and it is the state which, subsequently, has an impact on the transformation of its people into a higher organisational form, i.e. a nation.2 The final stage of those processes in Poland is relatively easily identifiable. It was at the turn of the 10th and 11th century when the name Poland was used for the first time to denote a country under the superior authority of the duke of Gniezno, and the country inhabitants, as attested in early historical sources.3 It is more difficult to determine the terminus a quo of the nation formation and the emergence of Po- land’s statehood. -

AMU Welcome Guide | 5 During the 123 Years Following the 1795 and German, Offered by 21 Faculties on 1

WelcomeWelcome Guide Guide Welcome Guide The Project is financed by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange under the Welcome to Poland Programme, as part of the Operational Programme Knowledge Education Development co-financed by the European Social Fund Welcome from the AMU Rector 3 Welcome from AMU Vice-Rector for International Cooperation 4 1. AdaM Mickiewicz UniversitY 6 1.1. Introduction 6 1.2. International cooperation 7 1.3. Faculties 9 Poznań campus 9 Kalisz campus – Faculty of Fine Arts and Pedagogy 9 Gniezno campus – Institute of European Culture 10 Piła campus – Nadnotecki Institute 10 Słubice campus – Collegium Polonicum 10 1.4. Main AMU Library (ul. Ratajczaka, Poznań) 11 1.6. School of Polish Language and Culture 13 2. Study witH us! 14 2.1. Calendar 14 Table of 2.2. International Centre is here to help! 16 2.3. Admission 17 Content 2.3.1. Enrolment in short 21 2.4. Dormitories 23 2.5. NAWA Polish Governmental Scholarships 24 2.6. Student organizations and Science Clubs 26 2.7. Activities for Students 27 3. LivinG In POlanD 32 3.1. Get to know our country! 32 3.2. Travelling around Poland 34 3.3. Health care 37 3.4. Everyday life 40 3.5. Weather 45 3.6. Documents 47 3.7. Migrant Info Point 49 4. PoznaŃ anD WIelkopolska – your neW home! 50 4.1. Welcome to our region 50 4.2. Explore Poznań 51 4.3. Cultural offer 57 4.4. Be active 60 4.5. Make Polish Friends 61 4.6. Enjoy life 62 4.7. -

How to Enhance the Environmental Values of Contemporary Cemeteries in an Urban Context

sustainability Article How to Enhance the Environmental Values of Contemporary Cemeteries in an Urban Context Długozima Anna * and Kosiacka-Beck Ewa Department of Landscape Art, Institute of Environmental Engineering, Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW, Warsaw, Nowoursynowska 166 St., 02 787 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 24 February 2020; Accepted: 17 March 2020; Published: 18 March 2020 Abstract: The cemetery is an important element of the city’s natural system. It can create a system that has a great impact on shaping the city’s climate if it is integrated with the local landscape, designed with respect for the natural environment along with other green areas. In the face of negative demographic forecasts, urbanization and suburbanization processes, and climate change, the use of pro-environmental solutions in the development of cemeteries cannot be overestimated. On the basis of analyses of contemporary cemeteries from Europe (78 objects), including Poland (8 objects), a catalog of pro-environmental solutions is developed. The catalog is created based on the proposed functional and spatial model of cemeteries as a multifunctional space, integrating natural and cultural environments. Environmental activities related to the context, burial space, architecture, and other spatial elements, as well as the vegetation of modern cemeteries, are included. Then, in order to increase the environmental values of the cemetery, these solutions were implemented by developing an integrated concept for the project of a multifunctional and ecological municipal cemetery in Gniezno, Poland (the Greater Poland voivodeship). Keywords: cemetery; pro-environmental solutions; urban landscape; burial space; multi-faceted cemetery model 1. -

The Holy See

The Holy See POPE JOHN PAUL II GENERAL AUDIENCE Wednesday, 18 June 1997 Historic celebrations marked Polish visit 1. I would like to begin today’s meeting by telling you about the recent pilgrimage to Poland which divine Providence gave me the opportunity to make. There were three principal reasons for this Pastoral Visit: the International Eucharistic Congress in Wroclaw, the 1,000th anniversary of St Adalbert’s martyrdom and the 600th anniversary of the foundation of the Jagiellonian University of Kraków. These events were the nucleus of the whole itinerary, which from 31 May to 10 June included Wroclaw, Legnica, Gorzów, Wielkopolski, Gniezno, Poznañ, Kalisz, Czêstochowa, Zakopane, LudŸmierz, Kraków, Dukla and Krosno, concentrating on three great cities: Wroclaw, the site of the 46th International Eucharistic Congress, Gniezno, a city linked with the death of St Adalbert, and Kraków, where the Jagiellonian University was founded. 2. The 46th International Eucharistic Congress in Wroclaw began on Trinity Sunday, 25 May, with the Eucharistic celebration presided at by my Legate, Cardinal Angelo Sodano, Secretary of State. A rich spiritual and liturgical programme filled the entire week, centring on the main theme: “For freedom Christ has set us free” (Gal 5:1). The Lord enabled me to take part in the conclusion of the work and so, on the last day of May, I was able to venerate Christ in the Eucharist, adoring him in the cathedral of Wroclaw together with people who had come from all over the world. That same day I took part in an ecumenical prayer service with representatives of the Churches and Ecclesial Communities. -

Foundation Myths and Dynastic Tradition of the Piasts and the Přemyslides in the Chronicles of Gallus Anonymus and Cosmas of Prague

Czech-Polish Historical and Pedagogical Journal 13 Who, where and why? Foundation Myths and Dynastic Tradition of the Piasts and the Přemyslides in the Chronicles of Gallus Anonymus and Cosmas of Prague Piotr Goltz / e-mail: [email protected] Faculty of History, University of Warsaw, Poland Goltz, P. (2016). Who, where and why? Foundation Myths and Dynastic Tradition of the Piasts and the Přemyslides in the Chronicles of Gallus Anonymus and Cosmas of Prague. Czech-Polish Historical and Pedagogical Journal, 8/2, 13–43. Much has been written about each of the medieval chronicles by academics from various fields of studies. If anything should be added, it seems that possibilities lie in a comparative study of the medieval texts. There are several reasons to justify such an approach to the chronicles by Anonymus called Gallus and Cosmas of Prague. Both narratives were written in a similar time period, in neighbouring countries, becoming evidence for the conscious forming of a dynastic vision of the past, as well as milestones in passing from the oral to the written form of collecting, selecting and passing on of tradition. Also similar is the scope of the authors’ interests, as well as the literary genre and courtly and chivalric character of their works. Firstly, the founding myths will be deconstructed in a search for three fundamental elements that determine the shape of the community: the main character, the place and the causing force. Secondly, a comparison of both bodies of lore will follow. Key words: Gallus Anonymus; Cosmas of Prague; myth; dynastic tradition The research presented herein belongs to the discipline of comparative historical studies.1 I am focusing on the foundation Motto: Fontenelle de, M. -

The Methodian Mission on the Polish Lands Until the Dawn of 11Th Century

ELPIS . Rocznik XV (XXVI) . Zeszyt 27 (40) . 2013 . s. 17-32 th E mE t h o d i a n m i s s i o n o n t h E po l i s h l a n d s t h u n t i l t h E d a w n o f 11 c E n t u r y mi s j a m E t o d i a ń s k a n a z i E m i a c h p o l s k i c h d o k o ń c a Xi w i E k u an t o n i mi r o n o w i c z un i w E r s y t E t w bi a ł y m s t o k u , a m i r @u w b .E d u .p l Słowa kluczowe: Misja chrystianizacyjna, Kościół w Polsce, misja metodiańska Keywords: Byzantine Church; Great Moravia; Poland; Sts Cyril and Methodius The process of Conversion of the Slavs was com- The younger brother, Constantine having gained a de- menced with the contact of the Slavic people and the Byz- cent education at home continued his studies in Constanti- antine culture which was initiated by the mission of Sts. nople. He entered a monastery in the capital of Byzantium Cyril and Methodius. Apart from the exceptional role of and received the minor holy orders (deacon). Thereafter, Bulgaria and the Great Moravia in the development of the Constantine adopted the position of chartophylax (librar- Cyrillo-Methodian legacy the Ruthenian lands became the ian) from the patriarch Ignatius (847-858, 867-877) at the heir of this great religious and cultural tradition. -

Vernacular Historiography in Medieval Czech Lands

VERNACULAR HISTORIOGRAPHY IN MEDIEVAL CZECH LANDS Marie Bláhová Univerzita Karlova z Praze Marie.Blahova@ff.cuni.cz Abstract In this work, it is offered an overview of medieval historiography in the Czech lands from origins to the fifteenth century, both in Latin and in the vernacular languages, as well as the factors that contributed to their development and dissemination. Keywords Vernacular Historiography, Czech Chronicles, Medieval Czech Literature. Resumen En este trabajo, se ofrece una visión de conjunto de la historiografía medieval en los terrorios checos desde orígenes hasta el siglo XV, tanto en latín como en las lenguas vernáculas, así como de los factores que contribuyeron a su elaboración y difusión. Palabras clave Historiografía vernácula, Crónicas checas, Literatura checa medieval. Te territory that would become the Czech Lands did not have a tradition of Classical culture. Bohemia and Moravia became acquainted with written culture, one of its integral parts, only after Christianity started to spread to this area in the 9th century. After a brief period in the 9th century when liturgy and culture in Moravia were mainly Slavic, the Czech Lands, much like the rest of Central Eu- rope, came to be dominated by the Latin culture and for several centuries Latin remained the only language of written records. Alongside the lives of saints and hagiographic legends which helped promote Christianity,1 historical records and later also larger, coherent historical narra- 1 Cf. Kubín (2011). MEDIEVALIA 19/1 (2016), 33-65 ISSN: 2014-8410 (digital) 34 MARIE BLÁHOVÁ tives2 are among the oldest products of written culture in the Czech Lands.3 Tey were created in the newly established ecclesiastical institutions, such as the episcopal church in Prague and the oldest monasteries. -

“What Sort of Communists Are You?” the Struggle Between Nationalism and Ideology in Poland Between 1944 and 1956

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2017 “What sort of communists are you?” The struggle between nationalism and ideology in Poland between 1944 and 1956 Jan Ryszard Kozdra Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Kozdra, J. R. (2017). “What sort of communists are you?” The struggle between nationalism and ideology in Poland between 1944 and 1956. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1955 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1955 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).