Trajectories of the Castrato from the Seventeenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Witches, Whores, and Virgin Martyrs: Female Roles in Seventeenth Century Opera Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9mj7d63c Author Richter, Terri Lynn Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Witches, Whores, and Virgin Martyrs: Female Roles in Seventeenth Century Opera A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Terri Lynn Richter 2017 Copyright by Terri Lynn Richter 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Witches, Whores, and Virgin Martyrs: Female Opera Roles in Seventeenth Century Opera by Terri Lynn Richter Doctor of Musical Arts in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Juliana K. Gondek, Chair The fictional women presented to the public on the opera stages and in the noble houses of Italy during the seventeenth century did not resemble the societal feminine ideal of chastity, silence, obedience, and humility; on the contrary, they were strong-willed, eloquent, powerful, and sexually sentient. This dissertation will examine a few of the principal female characters from a selected number of early seventeenth-century operas and explore what these women represented in context of the patriarchal, highly misogynistic societies in which they were constructed. Furthermore, I will consider the implications of this information for issues of modern performance practice, and for the representation of these female characters in modern reproductions of the operas. Finally, I will discuss the influences of this research on my final DMA recital, a program of seventeenth-century arias and songs which personified the female stereotypes presented in this dissertation. -

Guida Utente Diva

Guida Utente Diva versione 1.1 - Howard Scarr (2012) Traduzione italiana a cura di Mario Bianchi ● Introduzione 4 installazione / rimozione..........................................................................................4 risorse online...........................................................................................................4 il team u-he.............................................................................................................4 ringraziamenti speciali.............................................................................................4 spirito analogico.......................................................................................5 filtri zero delay feedback..........................................................................................5 accuratezza.............................................................................................................5 caricamento di preset..............................................................................6 cartella MIDI Programs............................................................................................6 preferiti, junk, reveal................................................................................................6 salvataggio di preset................................................................................7 funzioni drag & drop................................................................................................7 modifica.....................................................................................................7 -

Bel Canto: an Analysis from Birth and Background to Musical Benefaction Kaitlin Kohler Cedarville University, [email protected]

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2019 yS mposium Apr 3rd, 2:30 PM - 3:00 PM Bel Canto: An Analysis from Birth and Background to Musical Benefaction Kaitlin Kohler Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Kohler, Kaitlin, "Bel Canto: An Analysis from Birth and Background to Musical Benefaction" (2019). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 2. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2019/podium_presentations/2 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. B E L C A N T O An Analysis from Background and Birth to Benefaction Kaitlin Kohler Cedarville University What is bel canto? • Beautiful singing • Emphasis on the solo voice • Highly expressive and emotional • Quote from Robert Toft • Many historians believe bel canto originated with Giulio Caccini, the alleged founder of the aria for solo voice with instrumental accompaniment. • Reality: there are more avenues of origin than one man. Bel canto comes from many different Italian musical traditions. from -

TABLE of CONTENTS Historical Roots of Opera Singing 37 Body

TABLE of CONTENTS My Adventurous Journey - from a lost 11 Speaking Voice to a Coloratura Soprano Historical Roots of Opera Singing 37 Farinelli - Male Soprano & true Belcantist 45 Secrets of Opera Training, a Definition 50 of the Famous Italian A of Belcanto APPOGGIO - or How to Sustain the Voice 54 ATTACCA - Start & End of a Tone 56 AVANTI -the Front Position of the Tone 62 ALTO IN PALATO - The Raised Palate 67 Enrico Caruso & Luisa Tetrazzini - 69 Golden Throats or Perfect Voice Training? Singing by Natural Body Use - Teacher, 79 Therapy or Self Awareness? Body - the Instrument of the Soul 85 Correct or Careless Posture - 85 Head, Neck and Body Activate your Pelvic Floor 92 The Navel Lift for Wellbeing & a Slim Line 94 Washboard with Navel Lift 96 From Lying Position to Standing Ovations 98 Squatting like Oriental Street Hawkers 105 A Trick of the Proud African - for the Head 107 Singer's Throat - the Human Bird 112 Voice Box- a Miracle of Creation - 112 a Short Anatomy of the Larynx 5 http://d-nb.info/1036972151 Body Symmetry and a Balanced Throat 119 Tongue, Root of Tongue and Jaws - 123 Choir Members for the Tone Massage, Turn & Biter - the Remedies 128 for the Tongue Dumpling Moshe Feldenkrais'Tongue Turn 126 Kristin Linklater's Tongue Biter 128 Cork, Rubber & Key Tag - Some Tricks 131 to Relax your Jaws The High Palate - every Singer's Cathedral 138 Suck your Finger Tips instead of Biting your 141 Nails Avanti, Avanti - the Front Position of 144 the Voice - the Balcony of the Diva Harley Buzzer & Fluttering Lips for 148 'Avanti' -

Introduction : Why Melodrama?

INTRODUCTION : WHY MELODRAMA? Of all the non-professional actors who appeared in post-war Italian cinema, one not usually considered as belonging to a neorealist impulse is Lidia Cirillo. Filmed sitting on a train at the beginning of Una donna ha ucciso [A Woman Has Killed] (Vittorio Cottafavi, 1952), she tells an apparently suicidal fellow female passenger her cautionary tale. This woman has killed, and the story is her own – that is, the story the film is based on is that of a real murder, carried out by Cirillo on her husband, an English soldier. In her study of women in post-war Italy, Garofalo noted that the public was in many ways approving in its reaction to the crime. In her defence Cirillo told the court: ‘I wanted to avenge, along with my honour, that of all the women of Italy’ (Garofalo 1956: 20). What connection does this comment reveal between the particular and the general? Is it revenge against an apparent liberator – a member of the Allied armies who had just freed the country from the Nazis, a redeemer of distressed damsels turned into a stranger within the home? Is this symbolic of Italian reconstruction, of the disappointment in life after the Liberation? In her claim to speak for ‘all the women of Italy’, does she testify to an explosive violence underlying the institution of marriage, or of the return of the repressed of war to the domestic sphere? Is it an overturning of gender relations, a sign of feminine hysteria, that prison is indistinguishable from an unhappy family? Or does it offer a moral tale of deplorable transgression, of the futility of the desire for fulfilment for women, or the language of resistance in the renewed conservatism prior to feminism? The film takes inspiration from a news event, one which seems itself inspired by a film. -

Using Singing Voice Vibrato As a Control Parameter in a Chamber Oper

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper presented at Proceedings of International Computer Music Conference (ICMC). Citation for the original published paper: Einarsson, A., Friberg, A. (2015) Using Singing Voice Vibrato as a Control Parameter in a Chamber Oper. In: Using Singing Voice Vibrato as a Control Parameter in a Chamber Opera N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-179637 ICMC 2015 – Sept. 25 - Oct. 1, 2015 – CEMI, University of North Texas Using Singing Voice Vibrato as a Control Parameter in a Chamber Opera Anna Einarsson AndersFriberg Friberg KMH Royal College of Music, KTH Royal Institutete of of Technology, Technology, Stockholm Stocholmkholm [email protected] [email protected] In this work, we started with singing voice vibrato and ABSTRACT developed an extraction method inspired by a previous Even though a vast number of tools exist for real time voice model [1]. In the below described context of the chamber analyses, only a limited number of them focus specifically opera Ps! Jag kommer snart hem! [2] we then explored a on singing voice, and even less on features seen from a beta-version of the vibrato extraction model, in relation to perceptual viewpoint. This paper presents a first step to- how it may be used as a mean for affecting subsequent elec- wards a multi-feature analysis-tool of the singing voice in a tronic sounds in computer assisted composition, and how composer-researcher collaboration. -

"Casta Diva" from Bellini's

“Casta Diva” from Bellini's “Norma”--Rosa Ponselle; accompanied by the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Giulio Setti (December 31, 1928 and January 30, 1929) Added to the National Registry: 2007 Essay by Judy Tsou (guest post)* Rosa Ponselle “Casta Diva” is the most famous aria of Vincenzo Bellini’s “Norma” (1831). It is sung by the title character, a Druidess or priestess of the Gauls, in the first act. The opera takes place in Gaul between 100 and 50 BCE when the Romans were occupiers. The Gauls want Norma to declare war on the Romans, who have been oppressing them. Norma is hesitant to do so because she is secretly in love with Pollione, the Roman proconsul, and with whom she has borne two children. She assuages the people’s anger and convinces them that this is not the right time to revolt. She asserts that the Romans will eventually fall by their own doing, and the Gauls do not need to rise up now. It is at this point that Norma sings “Casta Diva,” a prayer to the moon goddess for peace, and eventually, conquering the Romans. When things between her and Pollione go sour, Norma tries to kill their children but ultimately cannot bring herself to do so. Eventually, she confesses her relationship with Pollione and sacrifices herself on the funeral pyre of her lover. “Norma” was the first of two operas commissioned in 1830 for which Bellini was paid an unprecedented 12,000 lire. “Norma” premiered on December 26, 1831 at La Scala, and the second opera, “Beatrice di Tenda,” premiered in 1833, but in Venice (La Fenice). -

“Can't Help Singing”: the “Modern” Opera Diva In

“CAN’T HELP SINGING”: THE “MODERN” OPERA DIVA IN HOLLYWOOD FILM, 1930–1950 Gina Bombola A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Annegret Fauser Tim Carter Mark Katz Chérie Rivers Ndaliko Jocelyn Neal ©2017 Gina Bombola ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Gina Bombola: “Can’t Help Singing”: The “Modern” Opera Diva in Hollywood Film, 1930–1950 (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) Following the release of Columbia Pictures’ surprise smash hit, One Night of Love (1934), major Hollywood studios sought to cash in on the public’s burgeoning interest in films featuring opera singers. For a brief period thereafter, renowned Metropolitan Opera artists such as Grace Moore and Lily Pons fared well at the box office, bringing “elite” musical culture to general audiences for a relatively inexpensive price. By the 1940s, however, the studios began grooming their own operatic actresses instead of transplanting celebrities from the stage. Stars such as Deanna Durbin, Kathryn Grayson, and Jane Powell thereby became ambassadors of opera from the highly commercial studio lot. My dissertation traces the shifts in film production and marketing of operatic singers in association with the rise of such cultural phenomena as the music-appreciation movement, all contextualized within the changing social and political landscapes of the United States spanning the Great Depression to the Cold War. Drawing on a variety of methodologies—including, among others, archival research, film analysis, feminist criticisms, and social theory—I argue that Hollywood framed opera as less of a European theatrical art performed in elite venues and more of a democratic, albeit still white, musical tradition that could be sung by talented individuals in any location. -

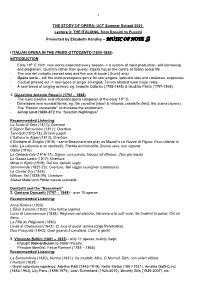

1 the STORY of OPERA: UCT Summer School 2021: Lecture 3

1 THE STORY OF OPERA: UCT Summer School 2021: Lecture 3: THE ITALIANS, from Rossini to Puccini Presented by Elizabeth Handley – MUSIC OF NOTE ♫ I ITALIAN OPERA IN THE PRIMO OTTOCENTO (1800-1850) INTRODUCTION - Early 19th C ItalY: new works expected every season -> a system of rapid production, self-borrowing and plagiarism. Quantity rather than quality. Opera house the centre of Italian social life. - The aria del sorbetto (sorbet aria) and the aria di baule ( [trunk] aria). - Opera seria – still the most prestigious genre for star singers: splendid sets and costumes, expensive. - Castrati phased out -> new types of singer emerged. Tenors allotted more major roles. - A new breed of singing actress, eg. Isabella Colbran (1785-1845) & Giuditta Pasta (1797-1865). 1. Gioachino Antonio Rossini (1792 – 1868) - The most creative and influential opera composer of the early 19th C. - Developed new musical forms, eg. the cavatina (slow) & virtuosic cabaletta (fast); the scena (scene). - The “Rossini crescendo”: to increase the excitement. - Jenny Lind (1820-87): the “Swedish Nightingale”. Recommended Listening: La Scala di Seta (1812): Overture Il Signor Beruschino (1812): Overture Tancredi (1812-13): Di tanti palpiti L’Italiana in Algeri (1813): Overture Il Barbiere di Siviglia (1816) - same Beaumarchais play as Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro: Ecco ridente in cielo, La calunnia e un venticello, Fredda ed immobile, Buona sera, mio signore Otello (1816) La Cenerentola (1816-17): Signor, una parola, Nacqui all’affanno...Non piu mesta La Gazza Ladra (1817): Overture Mosè in Egito (1818): Dal tuo stellato soglo Semiramide (1822-23): Overture, Bel raggio lusinghier (coloratura) Le Comte Ory (1828) William Tell (1828-29): Overture Stabat Mater and Petite messe solonelle Donizetti and the “Rossiniani” 2. -

User Manual • This Voiceone Quickstart Manual • Voiceone Preset, Style and Application Pamphlet • TC-Electronic Catalog • Warranty Card

VoiceOne Voice Pitch and Modeling Tool USER’S MANUAL IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS The lightning flash with an arrowhead The exclamation point within an symbol within an equilateral triangle, is equilateral triangle is intended to alert intended to alert the user to the the user to the presence of important presence of uninsulated "dangerous voltage" operating and maintenance (servicing) within the product's enclosure that may be of instructions in the literature accompanying the sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of product. electric shock to persons. 1 Read these instructions. Warning! 2 Keep these instructions. • To reduce the risk of fire or electric shock, 3 Heed all warnings. do not expose this apparatus to rain or 4 Follow all instructions. moisture. 5 Do not use this apparatus near water. • This apparatus must be earthed. 6 Clean only with dry cloth. • Use a three wire grounding type line cord 7 Do not block any ventilation openings. like the one supplied with the product. Install in accordance with the • Be advised that different operating voltages manufacturer's instructions. require the use of different types of line 8 Do not install near any heat sources such cord and attachment plugs. as radiators, heat registers, stoves, or other • Check the voltage in your area and use the apparatus (including amplifiers) that correct type. See table below: produce heat. 9 Do not defeat the safety purpose of the Voltage Line plug according to standard polarized or grounding-type plug. A 110-125V UL817 and CSA C22.2 no 42. polarized plug has two blades with one wider than the other. -

Diva: Early Film Culture and Image Theory in Italy

Dalle Vacche, Angela. Diva: Defiance and Passion in Early Italian Cinema. Austin: University of Texas Press, March 2008. Introduction. Mater Dolorosa A “diva” is the most important woman singer, the prima donna on the stage of opera, but this word can also describe an arrogant or temperamental woman. Close to the English word divine, “diva” means goddess, while the label “diva” competes for the spotlight with God, the ultimate divine maker of stars. Whereas God coincides with eternity, stars live and die. The point here is that the word diva strives for timelessness and infinity. By contrast, the word star is about someone special or exceptional or super-human (1), but not comparable to a divinity. In her best moments, the diva involves a certain kind of ineffable spirituality, ritualistic otherness, and an intuitive aura about transcendence. In short, the diva is an anomalous “star” in comparison to the Hollywood model which has defined film stardom for the rest of the world. The diva’s unusual contribution to the history of stardom stems from the cultural specificities of Italian modernity. In early Italian cinema, “diva” meant female star in a “long” feature film of at least sixty minutes, with some close- ups for the heroine and a fairly static use of the camera. The 12 point-of-view shot and the shot reverse shot, two basic features of classical American cinema, did not exist in the Italian films made between 1913 and 1918. However, the point-of-view shot begins to appear around 1919 or 1920 in diva-films. The three most famous divas of this period were Francesca Bertini (1892-1985), Lyda Borelli (1887-1959), and Pina Menichelli (1890-1984). -

Adelina Patti and Clara Louise Kellogg in the Chicago Tribune, 1860-1876

DOCUMENTING DIVAS: ADELINA PATTI AND CLARA LOUISE KELLOGG IN THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE, 1860-1876 Kathryn Jancaus A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC December 2020 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Ryan Ebright © 2020 Kathryn Jancaus All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor When Swedish soprano Jenny Lind (1820-1887) came to the United States in 1850, the ecstatic craze surrounding her arrival belied a larger trend which was taking root among the American press and public: a fascination with the lives of celebrity opera singers. One of the Lind enthusiasts was a college student named George P. Upton (1834-1919), who later became the music critic for the Chicago Tribune. In his work over the following decades, Upton continued to take a vivid interest in the lives, careers, and personalities of prima donnas, writing about them with an intensely personal style that was common in newspapers of his time. As journalists for the Tribune provided news about opera stars to their readers in Chicago, they not only shaped the public images of these singers but also promoted the appreciation of classical music as a cause for civic pride in their relatively young city. In this study I examine how George P. Upton and other journalists published in the Chicago Tribune wrote about two star sopranos of the mid to late nineteenth century: Adelina Patti (1843-1919) and Clara Louise Kellogg (1842-1916). I bring together newspaper articles from the years 1860 through 1876 and use secondary literature to place the critics’ approach in context.