Summary of Public Comments and Service Responses on the Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Impact Statement for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Stormwater Management Report

Municipality/Organization: Boston Water and Sewer Commission EPA NPDES Permit Number: MASO 10001 Report/Reporting Period: January 1, 2017-December 31, 2017 NPDES Phase I Permit Annual Report General Information Contact Person: Amy M. Schofield Title: Project Manager Telephone #: 617-989-7432 Email: [email protected] Certification: I certify under penalty of law that this document and all attachments were prepared under my direction or supervision in accordance with a system designed to assure that qualified personnel properly gather and evaluate the information submitted. Based on my inquiry of the person or persons who manage the system, or those persons directly responsible for gathering the information, the information submitted is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, true, accuratnd complete. I am aware that there are significant penalties for submitting false ivfothnation intdng the possibiLity of fine and imprisonment for knowing violatti Title: Chief Engineer and Operations Officer Date: / TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Permit History…………………………………………….. ……………. 1-1 1.2 Annual Report Requirements…………………………………………... 1-1 1.3 Commission Jurisdiction and Legal Authority for Drainage System and Stormwater Management……………………… 1-2 1.4 Storm Drains Owned and Stormwater Activities Performed by Others…………………………………………………… 1-3 1.5 Characterization of Separated Sub-Catchment Areas….…………… 1-4 1.6 Mapping of Sub-Catchment Areas and Outfall Locations ………….. 1-4 2.0 FIELD SCREENING, SUB-CATCHMENT AREA INVESTIGATIONS AND ILLICIT DISCHARGE REMEDIATION 2.1 Field Screening…………………………………………………………… 2-1 2.2 Sub-Catchment Area Prioritization…………………………………..… 2-4 2.3 Status of Sub-Catchment Investigations……………………….…. 2-7 2.4 Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination Plan ……………………… 2-7 2.5 Illicit Discharge Investigation Contracts……………….………………. -

Registered Starclubs

STARCLUB Registered Organisations Level 1 - REGISTERED in STARCLUB – basic information supplied Level 2 - SUBMITTED responses to all questions/drop downs Level 3 - PROVISIONAL ONLINE STATUS - unverified Level 4 - Full STARCLUB RECOGNITION Organisation Sports Council SC Level 1st Hillcrest Scout Group Scout Group Port Adelaide Enfield 3 (City of) 1st Nuriootpsa Scout Group Youth development Barossa Council 3 1st Strathalbyn Scouts Scouts Alexandrina Council 1 1st Wallaroo Scout Group Outdoor recreation and Yorke Peninsula 3 camping Council 3ballsa Basketball Charles Sturt (City of) 1 Acacia Calisthenics Club Calisthenics Mount Barker (District 2 Council of) Acacia Gold Vaulting Club Inc Equestrian Barossa Council 3 Active Fitness & Lifestyle Group Group Fitness Adelaide Hills Council 1 Adelaide Adrenaline Ice Hockey Ice Hockey West Torrens (City of) 1 Adelaide and Suburban Cricket Association Cricket Marion (City of) 2 Adelaide Archery Club Inc Archery Adelaide City Council 2 Adelaide Bangladesh Tigers Sporting & Cricket Port Adelaide Enfield 3 Recreati (City of) Adelaide Baseball Club Inc. Baseball West Torrens (City of) 2 Adelaide Boomers Korfball Club Korfball Onkaparinga (City of) 2 Adelaide Bowling Club Bowls Adelaide City Council 2 Adelaide Bushwalkers Inc Bushwalker Activities Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide Canoe Club Canoeing Charles Sturt (City of) 2 Adelaide Cavaliers Cricket Club Cricket Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide City Council Club development Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide City Football Club Football (Soccer) Port -

TOWN of MASHPEE BLUE PAGES a Citizens’ Guide to Protecting Cape Cod Waters

TOWN OF MASHPEE BLUE PAGES A Citizens’ Guide to Protecting Cape Cod Waters Shannon Cushing, Grade 11 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements This information is reprinted from the Island Blue Pages, courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group and the WampanoagThis information Tribe ofis Aquinnah.reprinted from For the a complete Island Blue version Pages of, courtesy the Island of theBlue Martha’s Pages, visit Vineyard the website Shellfish www.islandbluepages.org Group and the . or contactWampanoag tbe Martha’s Tribe Vineyardof Aquinnah. Shellfish For a Groupcomplete at 508version-693-0391. of the TheIsland Island Blue BluePages Pages, visit isthe an website adaptation, www.islandbluepages.org with permission, of the. or Pugetcontact Soundbook tbe Martha’s, a game Vineyard plan for Shellfish maintaining Group the at health508-693-0391. of our sister The Island estuary Blue on Pagesthe West is an Coast. adaptation, To learn with more permission, about the of the Puget Soundbook, a game plan for maintaining the health of our sister estuary on the West Coast. To learn more about the original project and the inspiration for the Blue Pages, visit www.forsea.org/pugetsoundbook/ original project and the inspiration for the Blue Pages, visit www.forsea.org/pugetsoundbook/ Thanks to Jim Kolb and Diane Bressler, the creators of the Puget Soundbook, which continues to inspire us with its words and Thanks to Jim Kolb and Diane Bressler, the creators of the Puget Soundbook, which continues to inspire us with its words and illustrations. illustrations. The Town of Mashpee, with permission, undertook the task of adapting the Orleans Blue Pages to reflect conditions specific to The Town of Mashpee, with permission, undertook the task of adapting the Orleans Blue Pages to reflect conditions specific to Mashpee. -

Springfield Ringette Association Handbook Updated April 2017 2017 Contents

SPRINGFIELD RINGETTE ASSOCIATION HANDBOOK Springfield Ringette Association Handbook updated April 2017 2017 Contents 1. Purpose of this Handbook ............................................................................................................................... 3 2. Governance ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Springfield Ringette Association Composition ............................................................................................... 3 4. Practices ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 5. Games ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 6. Tournaments .................................................................................................................................................... 6 7. Provincials ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 8. Player Development ........................................................................................................................................ 6 9. Team Selection Process .................................................................................................................................. -

Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All Hazardous Cargo (HC) and Cargo Tankers General Information Throughout Boston and Surrounding Towns

WELCOME TO MASSACHUSETTS! CONTACT INFORMATION REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCILS STATE ROAD LAWS NONRESIDENT PRIVILEGES Massachusetts grants the same privileges EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE Fire, Police, Ambulance: 911 16 to nonresidents as to Massachusetts residents. On behalf of the Commonwealth, MBTA PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 2 welcome to Massachusetts. In our MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 10 SPEED LAW Observe posted speed limits. The runs daily service on buses, trains, trolleys and ferries 14 3 great state, you can enjoy the rolling Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All hazardous cargo (HC) and cargo tankers General Information throughout Boston and surrounding towns. Stations can be identified 13 hills of the west and in under three by a black on a white, circular sign. Pay your fare with a 9 1 are prohibited from the Boston Tunnels. hours travel east to visit our pristine MassDOT Headquarters 857-368-4636 11 reusable, rechargeable CharlieCard (plastic) or CharlieTicket 12 DRUNK DRIVING LAWS Massachusetts enforces these laws rigorously. beaches. You will find a state full (toll free) 877-623-6846 (paper) that can be purchased at over 500 fare-vending machines 1. Greater Boston 9. MetroWest 4 MOBILE ELECTRONIC DEVICE LAWS Operators cannot use any of history and rich in diversity that (TTY) 857-368-0655 located at all subway stations and Logan airport terminals. At street- 2. North of Boston 10. Johnny Appleseed Trail 5 3. Greater Merrimack Valley 11. Central Massachusetts mobile electronic device to write, send, or read an electronic opens its doors to millions of visitors www.mass.gov/massdot level stations and local bus stops you pay on board. -

A History of the GAA from Cú Chulainn to Shefflin Education Department, GAA Museum, Croke Park How to Use This Pack Contents

Primary School Teachers Resource Pack A History of The GAA From Cú Chulainn to Shefflin Education Department, GAA Museum, Croke Park How to use this Pack Contents The GAA Museum is committed to creating a learning 1 The GAA Museum for Primary Schools environment and providing lifelong learning experiences which are meaningful, accessible, engaging and stimulating. 2 The Legend of Cú Chulainn – Teacher’s Notes The museum’s Education Department offers a range of learning 3 The Legend of Cú Chulainn – In the Classroom resources and activities which link directly to the Irish National Primary SESE History, SESE Geography, English, Visual Arts and 4 Seven Men in Thurles – Teacher’s Notes Physical Education Curricula. 5 Seven Men in Thurles – In the Classroom This resource pack is designed to help primary school teachers 6 Famous Matches: Bloody Sunday 1920 – plan an educational visit to the GAA Museum in Croke Park. The Teacher’s Notes pack includes information on the GAA Museum primary school education programme, along with ten different curriculum 7 Famous Matches: Bloody Sunday 1920 – linked GAA topics. Each topic includes teacher’s notes and In the Classroom classroom resources that have been chosen for its cross 8 Famous Matches: Thunder and Lightning Final curricular value. This resource pack contains everything you 1939 – Teacher’s Notes need to plan a successful, engaging and meaningful visit for your class to the GAA Museum. 9 Famous Matches: Thunder and Lightning Final 1939 – In the Classroom Teacher’s Notes 10 Famous Matches: New York Final 1947 – Teacher’s Notes provide background information on an Teacher’s Notes assortment of GAA topics which can be used when devising a lesson plan. -

The History of the Mashpee National Wildlife Refuge

HOW WE GOT HERE: The History of the Mashpee National Wildlife Refuge By the Friends of the Mashpee National Wildlife Refuge The Mashpee National Wildlife Refuge encompasses nearly 6,000 acres that protects important natural areas and a great diversity of wildlife habitat. Established in 1995, this unique refuge is owned by federal, state, town, and private conservation groups who share a common goal of conserving nature for the continued benefit of wildlife and people. PREFACE National Wildlife Refuges are valuable assets in a variety • Located in the towns of Mashpee and Falmouth, of ways. They provide a window into past cultures and with 6000 acres, it is the Cape’s second largest open, untouched landscapes while preserving these resources accessible conservation land, behind only the National well into the future, furthering the continuum. Refuges Seashore. sustain necessary wildlife habitats and resources critical in their seasonal needs for foraging, raising young, • It was named after the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, and avoiding predators to live yet another day. These “the people of the first light.” preserved landscapes purify water and air providing yet another valuable service. Likewise, for humans, refuges • It is unique within the National Wildlife Refuge offer solitude in our daily lives and, as the name implies, System in that it is the ONLY refuge that is managed are a great place to view wildlife too. cooperatively by eight conservation landowners and the Friends organization: a consortium of federal, state, I grew up in Minnesota, where we often headed to a tribal, private, & nonprofit. It’s the model for future local refuge in the spring to witness one of the most refuges. -

The Development of a Reliable and Valid Netball Intermittent Activity Test

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. THE DEVELOPMENT OF A RELIABLE AND VALID NETBALL INTERMITTENT ACTIVITY TEST A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Sport and Exercise Science at Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand HELEN JOANNE RYAN 2009 i ABSTRACT The purpose of the present investigation was to identify the exercise intensity of netball match play in order to assist in the development of a Netball Intermittent Activity Test (NIAT). A further aim was to assess the criterion validity and the test- retest reliability of the NIAT. Eleven female netball players (21.4 ± 3.1 years, 1.73 ± 0.06 m, 69.3 ± 5.3 kg and 48.4 ± 4.9 ml·kg-1·min–1 mean ± SD, age, height, body mass and & OV 2max, respectively) volunteered to participate in the study. Heart rate data was recorded for all participants from at least two full 60 minute games during Premier Club competition. Individual maximum heart rate values were acquired for all subjects from the performance of the Multistage Fitness Test, and used to transform heart rate recordings into percent maximum heart rate (%HRmax). Patterns in %HRmax were used to indicate positional grouping when developing the NIAT from time motion analysis data. Subjects performed two trials of the NIAT separated by at least seven days. -

The Winslows of Boston

Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV FAMILY MEMORIAL The Winslows of Boston Isaac Winslow Margaret Catherine Winslow IN FIVE VOLUMES VOLUME IV Boston, Massachusetts 1837?-1873? TRANSCRIBED AND EDITED BY ROBERT NEWSOM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE 2009-10 Not to be reproduced without permission of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV Editorial material Copyright © 2010 Robert Walker Newsom ___________________________________ All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this work, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission from the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts. Not to be reproduced without permission of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts Winslow Family Memorial, Volume IV A NOTE ON MARGARET’S PORTION OF THE MANUSCRIPT AND ITS TRANSCRIPTION AS PREVIOUSLY NOTED (ABOVE, III, 72 n.) MARGARET began her own journal prior to her father’s death and her decision to continue his Memorial. So there is some overlap between their portions. And her first entries in her journal are sparse, interrupted by a period of four years’ invalidism, and somewhat uncertain in their purpose or direction. There is also in these opening pages a great deal of material already treated by her father. But after her father’s death, and presumably after she had not only completed the twenty-four blank leaves that were left in it at his death, she also wrote an additional twenty pages before moving over to the present bound volumes, which I shall refer to as volumes four and five.* She does not paginate her own pages. I have supplied page numbers on the manuscript itself and entered these in outlined text boxes at the tops of the transcribed pages. -

A Different Kind of Where-To-Go- Birding: Ten Favorite Places of the Bird Observer Staff

A Different Kind of Where-to-go- Birding: Ten Favorite Places of the Bird Observer Staff For this thirtieth-anniversary issue, the editors, recent guest editors, department heads, and various other Bird Observer staff members collaborated on a project to describe their favorite places to watch birds, and why they like them so much. We began by trying to identify and summarize the ten best places to bird in Massachusetts (since that’s where the staff all live), but that quickly proved an impossible task. How could the best places be determined? Who would ever agree with our choices? So we decided to eschew politically charged decisions and concentrate on our favorite places instead. The following pieces are not intended to describe these places in detail, give directions, or provide comprehensive lists of birds seen there. They are short essays on why the particular staff member really likes to bird the place. Of course the authors include avian highlights, but the aim is to also offer insight into the more personal and aesthetic reasons that the selected location is a pleasure to bird. No two authors have gone about their task in the same way, and, indeed, there were few ground mles except to keep it short and personal. So sit back and enjoy the essays. You will quickly find that the staff have described what would generally be considered some of the best birding sites in Massachusetts, although most of them are in the eastern part of the state, an artifact of where the majority of the staff live. -

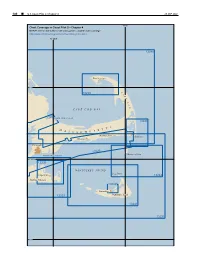

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

Town of Chatham ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Table of Contents

TOWN OF CHATHAM ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Table of Contents Elective Offices ...........................................................................2 Harbormaster .............................................................................68 Appointed Offices .......................................................................2 Board of Health ..........................................................................73 Committees .................................................................................4 Health and Environment ............................................................73 In Memoriam – 2011 ..................................................................7 Herring Warden ..........................................................................77 Board of Selectmen ....................................................................7 Historic Business District Commission .....................................77 Town Manager ............................................................................7 Historical Commission ..............................................................77 Annual Financial Reports ...........................................................8 Chatham Housing Authority ......................................................78 Annual Wages – Town Employees ...........................................48 Human Services Committee ......................................................78 Affordable Housing Committee ...............................................57 Land Bank Open Space Committee