An Additional Aspect of the Wartime Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOW^. ^Oor^Open^

an ex-patriate American woman Roland Culver, whose portrait of a flnd'"To Each His Own” too much Olivia Proves who looks very much like, Olivia De taciturn Lord Desham wooing the in the mood of those tearful enter- Havilland may look 25 years from middle-aged American woman is tainments contrived for the radio* now. These passing years are made j lighter for the audiences by some wonderfully comic. daylight hours. But Miss De Havil- Set to Tunes An Actress in There will be those, of course, who i land makes it worthwhile. Stock History Pretty bright glimpses of the varying ^^\Completo g American scene and some able Blank £\ by AMUSEMENTS AMUSEMENTS Earle Film work on the part of the players in- In Lavish Film volved. The most notable of these is Capitol ‘TO EACH HI8 OWN.'1 * Paramount Olivia De with Havilland, produced AMUSEMENTS All Official Pictures from BIKINI VE. Morrison Paper Co. £ / By Jay Carmody eicturey Charles Brackett, directed by Mitchell [At LOEW^i America's history is never more popularly sugar-coated than when Lelsen, screenplay by Charles Brackett and ^^1009 Penn. Ave. N.W. from an Theatres l it is covered with the sweet music of Jerome Kem or Jacques Thery original story by ATOM BOMB vs WARSHIP I Richard Rodgers, Mr. Brackett. At the Earle. with Oscar Hammerstein II as Under these lyricist. conditions, history THE CAST. becomes the most of all and screen themes. SPOT CASH! popular stage What it lacks Miss Norris _Olivia De Havilland of accuracy is more than balanced by what it has of melody and a hack- Corinne Piersen_Mary Anderson Desham_Roland Culver which itself off as Lord neyed quality passes gracefully old-fashioned charm. -

Performing Resistance: Myrna Loy, Joan Crawford, and Barbara Stanwyck in Postwar Cinema

Performing Resistance: Myrna Loy, Joan Crawford, and Barbara Stanwyck in Postwar Cinema Asher Benjamin Guthertz Film and Digital Media March 23, 2018 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Shelley Stamp This thesis has been completed according to the Film and Digital Media department's standards for undergraduate theses. It is submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Film and Digital Media. Introduction: Performing Resistance In the sunny California town of Santa Lisa, amidst a round of applause, veteran Frank Enley (Van Heflin) hands his toddler to his wife and struts onto a makeshift stage. In front of a crowd gathered to celebrate the opening of a new housing complex, he declares: “It was you fellas, you and your families, that really put this thing over. You stuck together and you fought for what you wanted, and if I gave you any help at all, well believe me, I am very happy.” His wife, holding their young son, beams. Frank musters all the spirit of war time camaraderie, and expresses that American belief that with hard work and a communal effort, anything is possible. But as Act of Violence (1949) unfolds, Frank’s opening speech becomes sickeningly hypocritical. A former army comrade sets out to murder Frank, and halfway through the film, Frank tells his wife Edith (Janet Leigh) why. The revelation takes place on an outdoors stairway at night. The railing and fences draw deep angular shadows on the white walls, and the canted angles sharpen the lines of the stairs and floor. A sense of enclosure looms; Frank mutters that he betrayed his troop. -

Centennial Summer N 1944, Meet Me in St

Centennial Summer n 1944, Meet Me in St. Louis and E.Y. Harburg. In the end, ev- favorably compared to Meet Me in captivated moviegoers the world eryone ends up where they want St. Louis by critics of the day, but Iover. The unbridled nostalgia for to be and happy endings abound. Centennial Summer is not that film a simpler time was very appealing and can stand proudly on its own in the turbulent war years. Two Centennial Summer was Jerome all these years later. It did receive years later, Twentieth Century-Fox Kern’s final score – he died in No- two Academy Award nominations, made its own film to appeal to that vember of 1945 at sixty years of both in the music category – for same audience – Centennial Sum- age, a great loss to the world of Best Music, Scoring of a Motion mer. With an excellent screenplay musical theatre and film. At the Picture for Alfred Newman, and by Michael Kanin and elegant and time of his death, Metro-Gold- Best Music, Original Song for “All stylish direction by Otto Preminger, wyn-Mayer was making a film Through the Day” by Kern and Centennial Summer takes a color- loosely based on his life (Till the Hammerstein – it lost both, but it ful, fun and even touching look at Clouds Roll By) and he’d just was a very competitive year. the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition begun work on a new musical, and one family’s trials and tribula- Annie Get Your Gun (Irving Berlin None of the stars of Centennial tions and follies and foibles. -

LINER NOTES Including the Show’S Transition from Radio to Make up for All That Had Been Stolen from Him

Advise and Consent law Josey Wales, The Enforcer, Demon Seed, He assembled a starry cast: Henry Fonda, and many others. His scores were brilliant, and Charles Laughton (whose final film it was), Don he had a unique musical voice. He was a three- ADVISE AND CONSENT Murray, Walter Pidgeon, Peter Lawford, Gene time Oscar nominee. Tierney (who’d starred in Preminger’s break- Adapted from the 1959 novel by Allen Drury, out film, Laura), Franchot Tone, Lew Ayres, In Advise and Consent, Fielding’s great sense Otto Preminger’s 1962 film of Advise and Con- Burgess Meredith, Paul Ford, George Griz- of melody is apparent from the first notes of sent was a hard-hitting political drama with zard, Inga Swenson, Edward Andrews, and its main theme, a beautiful piece that never an all-star cast. Preminger, by this time, was in a small role, Betty White. The screenplay overplays its musical hand in the film – it’s a expert at these kinds of films, but also one of was by the wonderful writer Wendell Mayes gorgeous melody, so gorgeous in fact that a the most eclectic of filmmakers, tackling what- (who’d done the screenplay for Preminger’s prominently credited Frank Sinatra sings the ever genre came his way and if that project Anatomy of a Murder and would subsequently theme, which is playing on a jukebox in the had some controversy, Preminger embraced it write Preminger’s film of In Harm’s Way), and infamous gay bar sequence. The song was en- rather vociferously. In those days, he was a the cameraman was Sam Leavitt (who’d pho- titled “Heart of Mine” and the lyric was by Ned groundbreaker – hiring Dalton Trumbo to write tographed Preminger’s Carmen Jones, The Washington. -

The Actress ART and REALITY

The Actress ART AND REALITY By RICHARD LIPPE George Cukor’s The Actress (1953) is a consistently overlooked must face the disapproval of her commonsensical father, film. In part this reaction may stem from the fact that the work, Clinton/Spencer Tracy, a man of little formal education who in scale and subject matter, suggests a modest project. barely supports his family, holding a low-paying, menial job. Additionally, The Actress , which is based on Ruth Gordon’s auto - The most extravagant aspect of Ruth’s life and image is her biographical play, Years Ago , has been eclipsed by the critical clothing that her mother sews. Ruth’s clothes are inspired by successes of the four Ruth Gordon/Garson Kanin/George Cukor the costumes she sees in theatre magazines and reflect her collaborations. The film, in fact, is treated often as the least sig - wish to be a part of that world of daring and glamour. The nificant of the various projects that involved Gordon and/or Actress, in foregrounding that the Joneses are an impoverished Kanin with Cukor. Yet, The Actress , in addition to embodying family, makes Ruth’s desire to be an actress, which she thinks Cukor’s thematic concerns, admirably illustrates again his abili - will make her rich and famous, both understandable and ty to respond to a project with original and fresh approach. seemingly foolish. The Actress belongs to the small town domestic comedy Not only do Meet Me in St. Louis and The Actress take oppo - genre and, given that it is a period film, it is a piece of site visual approaches, the films differ in their respective han - Americana in the tradition of Minnelli’s classic Meet Me in St. -

Appendix 1: Selected Films

Appendix 1: Selected Films The very random selection of films in this appendix may appear to be arbitrary, but it is an attempt to suggest, from a varied collection of titles not otherwise fully covered in this volume, that approaches to the treatment of sex in the cinema can represent a broad church indeed. Not all the films listed below are accomplished – and some are frankly maladroit – but they all have areas of interest in the ways in which they utilise some form of erotic expression. Barbarella (1968, directed by Roger Vadim) This French/Italian adaptation of the witty and transgressive science fiction comic strip embraces its own trash ethos with gusto, and creates an eccentric, utterly arti- ficial world for its foolhardy female astronaut, who Jane Fonda plays as basically a female Candide in space. The film is full of off- kilter sexuality, such as the evil Black Queen played by Anita Pallenberg as a predatory lesbian, while the opening scene features a space- suited figure stripping in zero gravity under the credits to reveal a naked Jane Fonda. Her peekaboo outfits in the film are cleverly designed, but belong firmly to the actress’s pre- feminist persona – although it might be argued that Barbarella herself, rather than being the sexual plaything for men one might imagine, in fact uses men to grant herself sexual gratification. The Blood Rose/La Rose Écorchée (aka Ravaged, 1970, directed by Claude Mulot) The delirious The Blood Rose was trumpeted as ‘The First Sex Horror Film Ever Made’. In its uncut European version, Claude Mulot’s film begins very much like an arthouse movie of the kind made by such directors as Alain Resnais: unortho- dox editing and tricks with time and the film’s chronology are used to destabilise the viewer. -

Twentieth Century Fox: 1935-1965

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release June 1990 Twentieth Century Fox: 1935-1965 July 1 - September 11, 1990 This summer, The Museum of Modern Art pays tribute to Twentieth Century Fox with a retrospective of over ninety films made between 1935 and 1965. Opening on July 1, 1990, TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX: 1935-1965 traces three key decades in the history of the studio, celebrating the talents of the artists on both sides of the cameras who shaped this period. The exhibition continues through September 11. Formed in 1915, the Fox Film Corporation merged in 1935 with the much younger Twentieth Century to launch a major new studio. Under the supervision of Darryl F. Zanuck, Twentieth Century Fox developed a new house style, emphasizing epic biographies such as John Ford's The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936) and Allan Dwan's Suez (1938) and snappy urban pictures such as Sidney Lanfield's Hake Up and Live (1937) and Roy Del Ruth's Thanks a Million (1935). The studio also featured such fresh screen personalities as Tyrone Power, Alice Faye, and Shirley Temple. From this time on, the studio masterfully anticipated and shaped the tastes of the movie-going public. During World War II, Twentieth Century Fox made its mark with a series of exuberant Technicolor musicals featuring such actresses as Betty Grable and Carmen Miranda. After the war, the studio shifted focus and began to highlight other genres including films noirs such as Edmund Goulding's Nightmare Alley (1947) and Otto Preminger's Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950), wry satirical films such as Joseph L. -

•Œfemme/S, Film/S, Noir/E

UCLA Thinking Gender Papers Title “Femme/s, Film/s, Noir/e: Revisions” Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/23s0b500 Author Stulman, Valerie Publication Date 2007-02-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Stulman 1 Femme/s, Film/s, Noir/e: Revisions Valerie Stulman “There is no one true version of which all the others are but copies or distortions. Every version belongs to the myth.” Claude Levi-Strauss, The Structural Study of Myth Thinking Gender 17th Annual Graduate Student Research Conference February 2, 2007 UCLA Stulman 2 “Femme/s, Film/s, Noir/e: Revisions” Film noir is a relatively small group of films, which span the years between World War II and the late 1950s. These films share a number of stylistic conventions which include the use of various permutations of stereotypical bad girl/femme fatale and good girl/household nun (Martin 207) type characters. In most of these films, women and their sexuality are considered to be (as Freud believed) “ a dark continent” (Breger 331), symbolically “Other” (Leitch 1283), outside the norm, therefore not ‘normal.’ This phallocentric bias permeates film noir (as well as most film up until that point, and since,) and “reflects the normal status of women within contemporary society” (Harvey 38). However, due to noir’s topsy-turvy nature, where contradictions, nightmares, narrative disconnects, and role reversals abound, “the normal representation of women as the founders of families undergoes an interesting displacement” (38). This displacement came about in society and film noir in part as a reaction to the horrifying effects of World War II on America and the survivors of the Nazi terror. -

Otto Preminger and the Surface of Cinema Christian Keathley in 100

Otto Preminger and the Surface of Cinema Christian Keathley In 100 Semesters–a lively, readable memoir of half a century in academics–William Chace describes a challenge he faced early in his teaching career as an English professor at Stanford. No sooner did he become a comfortably skilled college instructor than Chace began to suspect that his lectures on classics by Hemingway, Wharton, Fitzgerald, and the like were “saying no more than what a reasonably attentive and responsive reader could get out of those books unaccompanied by my help. I paused to think: was there anything to understand about The Great Gatsby that needed my guiding hand?” Chace’s response was to trade these (allegedly) “obvious” books for something more opaque–“a subject the ordinary reader would not read easily, or read at all, without help”–and so he began teaching a seminar on Joyce’s Ulysses. While the analogy between teaching literature and teaching film is obvious, Chace’s experience is exactly the opposite of my own. I find it far easier to teach “difficult” works like Vivre sa vie or L’Avventura than it is to teach transparent works like Casablanca or Winchester 73–and I’m talking about formal and aesthetic analysis here, not ideological. With the former films, students come in confused, perplexed, maybe irritated, but always in need of help understanding—help that I am well-equipped to give. But the latter films, so it seems, require no critical explication: they are so obviously what they are, and what they are is obvious. And therein lies the challenge. -

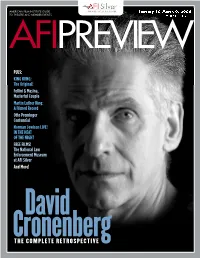

32 • Iissuessue 16 Afipreview

AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE Januaryuary 10–March 9, 2006 TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUMEVOLUME 32 • ISSUEISSUE 61 AFIPREVIEW PLUS: KING KONG: The Original! Fellini & Masina, Masterful Couple Martin Luther King: A Filmed Record Otto Preminger Centennial Norman Jewison LIVE! IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT FREE FILMS! The National Law Enforcement Museum at AFI Silver And More! David CronenbergTHE COMPLETE RETROSPECTIVE NOW PLAYING AWARD NIGHTS AT AFI 2 Oscar® and Grammy® Night Galas! 3 David Cronenberg: The Visceral BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! and the Cerebral ® 6 A True Hollywood Auteur: Otto Preminger Oscar Night 2006! 9 Norman Jewison Presents Sunday, March 5 IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT AFI Silver is proud to host the only Academy®- 9 Martin Luther King Honored sanctioned Oscar Night® party in the Washington area, 9 SILVERDOCS: Save the Date! presented by First Star. On Sunday, March 5, at 6:30 10 About AFI p.m., AFI Silver will be abuzz with red carpet arrivals, 11 Calendar specialty cocktails, a silent auction and a celebrity- 12 Federico Fellini and Giulietta Masina, moderated showing of the Oscar® Awards broadcast— Masterful Pair presented on-screen in high definition! 12 ANA Y LOS OTROS, Presented by Cinema Tropical All proceeds 13 THE FRENCH CONNECTION, SE7EN, and DRAGNET! from this National Law Enforcement Museum’s exclusive event Inaugural Film Festival benefit First 13 Washington, DC, Premiere of Star, a national Terrence Malick’s THE NEW WORLD non-profit 14 One Week Only! CLASSE TOUS RISQUES public charity and SPIRIT OF THE BEEHIVE dedicated to 14 Exclusive Washington Engagement! SYMBIOPSYCHOTAXIPLASM improving life 15 Montgomery College Film Series for child victims 15 Membership News: It Pays to of abuse and Be an AFI Member! neglect. -

Introduction to the European Convention on Human Rights

Introduction to the European Convention on Human Rights The rights guaranteed and the protection mechanism Jean-François Renucci Doctor, Professeur, University of Nice Sophia-Antipolis (France) Director, Centre d’études sur les droits de l’homme (CEDORE-IDPD) Council of Europe Publishing French edition Introduction générale à la Convention européenne des Droits de l’Homme: Droits garantis et mécanisme de protection ISBN 92-871-5714-6 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not engage the responsibility of the Council of Europe. They should not be regarded as placing upon the legal instruments mentioned in it any official interpretation capable of binding the governments of member states, the Council of Europe’s statutory organs or any organ set up by virtue of the European Convention on Human Rights. Council of Europe Publishing F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex ISBN 92-871-5715-4 © Council of Europe, 2005 1st printing June 2005 Printed at the Council of Europe Contents Introduction Part One: The rights guaranteed Chapter 1: General protection . 9 I. Civil and political rights. 9 A. The right to life . 9 B. Prohibition of ill-treatment . 12 1. The definition of ill-treatment . 13 2. Applicability of Article 3 . 14 3. Scope of Article 3 . 16 4. Proof of ill-treatment . 17 C. Prohibition of slavery and servitude . 18 D. Prohibition of discrimination . 19 1. Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights: a limited prohibition . 19 2. Protocol No. 12: a general prohibition . 21 E. Freedom of expression. 22 1. Affirmation of the principle of freedom . -

The Otto Preminger Film Noir Collection Limited Edition Blu-Ray Box Fallen Angel, Whirlpool, Where the Sidewalk Ends

The Otto Preminger Film Noir Collection Limited Edition Blu-ray box Fallen Angel, Whirlpool, Where the Sidewalk Ends Released on 28 September 2015, this Limited Edition box set brings together three of acclaimed director Otto Preminger’s greatest films for the first time on Blu-ray. Presented with essential extras, including audio commentaries, these classic films deliver a unique combination of intrigue, moral ambiguity and stylish photography which truly define the influential film noir genre. In Fallen Angel, Dana Andrews stars as a down-on-his-luck press agent turned amateur sleuth, investigating the murder of the sultry waitress, Stella (Linda Darnell). Whirlpool is a fascinating blend of noir and woman’s picture, starring the beautiful Gene Tierney as a troubled socialite who falls prey to the machinations of a sinister hypnotist (José Ferrer). Whilst in the downbeat Where the Sidewalk Ends, Dana Andrews again stars as a tough cop whose brutal methods leave a trail of murder, deceit and cover-ups. Special features All films presented in High Definition Original theatrical trailers Audio commentaries for Fallen Angel, Whirlpool and Where the Sidewalk Ends by film scholar and critic Adrian Martin The Guardian Lecture: Otto Preminger interviewed by Joan Bakewell (1972, 80 mins, audio with stills): the director talks about his career in film in this discussion with the English journalist Illustrated booklet with essays by Edward Buscombe and full film credits Blu-ray product details RRP: £59.99 / Cat. no. BFIB1216 / Cert 12 Fallen