(Acari: Ixodidae and Argasidae) Associated with Odocoileus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vector Hazard Report: Ticks of the Continental United States

Vector Hazard Report: Ticks of the Continental United States Notes, photos and habitat suitability models gathered from The Armed Forces Pest Management Board, VectorMap and The Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit VectorMap Armed Forces Pest Management Board Table of Contents 1. Background 4. Host Densities • Tick-borne diseases - Human Density • Climate of CONUS -Agriculture • Monthly Climate Maps • Tick-borne Disease Prevalence maps 5. References 2. Notes on Medically Important Ticks • Ixodes scapularis • Amblyomma americanum • Dermacentor variabilis • Amblyomma maculatum • Dermacentor andersoni • Ixodes pacificus 3. Habitat Suitability Models: Tick Vectors • Ixodes scapularis • Amblyomma americanum • Ixodes pacificus • Amblyomma maculatum • Dermacentor andersoni • Dermacentor variabilis Background Within the United States there are several tick-borne diseases (TBD) to consider. While most are not fatal, they can be quite debilitating and many have no known treatment or cure. Within the U.S., ticks are most active in the warmer months (April to September) and are most commonly found in forest edges with ample leaf litter, tall grass and shrubs. It is important to check yourself for ticks and tick bites after exposure to such areas. Dogs can also be infected with TBD and may also bring ticks into your home where they may feed on humans and spread disease (CDC, 2014). This report contains a list of common TBD along with background information about the vectors and habitat suitability models displaying predicted geographic distributions. Many tips and other information on preventing TBD are provided by the CDC, AFPMB or USAPHC. Back to Table of Contents Tick-Borne Diseases in the U.S. Lyme Disease Lyme disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi and the primary vector is Ixodes scapularis or more commonly known as the blacklegged or deer tick. -

Dermacentor Rhinocerinus (Denny 1843) (Acari : Lxodida: Ixodidae): Rede Scription of the Male, Female and Nymph and First Description of the Larva

Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res., 60:59-68 (1993) ABSTRACT KEIRANS, JAMES E. 1993. Dermacentor rhinocerinus (Denny 1843) (Acari : lxodida: Ixodidae): rede scription of the male, female and nymph and first description of the larva. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research, 60:59-68 (1993) Presented is a diagnosis of the male, female and nymph of Dermacentor rhinocerinus, and the 1st description of the larval stage. Adult Dermacentor rhinocerinus paras1tize both the black rhinoceros, Diceros bicornis, and the white rhinoceros, Ceratotherium simum. Although various other large mammals have been recorded as hosts for D. rhinocerinus, only the 2 species of rhinoceros are primary hosts for adults in various areas of east, central and southern Africa. Adults collected from vegetation in the Kruger National Park, Transvaal, South Africa were reared on rabbits at the Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute, where larvae were obtained for the 1st time. INTRODUCTION longs to the rhinoceros tick with the binomen Am blyomma rhinocerotis (De Geer, 1778). Although the genus Dermacentor is represented throughout the world by approximately 30 species, Schulze (1932) erected the genus Amblyocentorfor only 2 occur in the Afrotropical region. These are D. D. rhinocerinus. Present day workers have ignored circumguttatus Neumann, 1897, whose adults pa this genus since it is morphologically unnecessary, rasitize elephants, and D. rhinocerinus (Denny, but a few have relegated Amblyocentor to a sub 1843), whose adults parasitize both the black or genus of Dermacentor. hook-lipped rhinoceros, Diceros bicornis (Lin Two subspecific names have been attached to naeus, 1758), and the white or square-lipped rhino D. rhinocerinus. Neumann (191 0) erected D. -

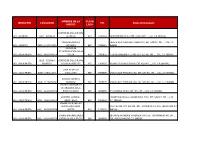

MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE LA UNIDAD CLAVE LADA TEL Domiciliocompleto

NOMBRE DE LA CLAVE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD TEL DomicilioCompleto UNIDAD LADA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 001 - ACONCHI 0001 - ACONCHI ACONCHI 623 2330060 INDEPENDENCIA NO. EXT. 20 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84920) CASA DE SALUD LA FRENTE A LA PLAZA DEL PUEBLO NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. 001 - ACONCHI 0003 - LA ESTANCIA ESTANCIA 623 2330401 (84929) UNIDAD DE DESINTOXICACION AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 3382875 7 ENTRE AVENIDA 4 Y 5 NO. EXT. 452 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) 0013 - COLONIA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 002 - AGUA PRIETA MORELOS COLONIA MORELOS 633 3369056 DOMICILIO CONOCIDO NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) CASA DE SALUD 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0009 - CABULLONA CABULLONA 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84305) CASA DE SALUD EL 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0046 - EL RUSBAYO RUSBAYO 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84306) CENTRO ANTIRRÁBICO VETERINARIO AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA SONORA 999 9999999 5 Y AVENIDA 17 NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) HOSPITAL GENERAL, CARRETERA VIEJA A CANANEA KM. 7 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA AGUA PRIETA 633 1222152 C.P. (84250) UNEME CAPA CENTRO NUEVA VIDA AGUA CALLE 42 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , AVENIDA 8 Y 9, COL. LOS OLIVOS C.P. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 1216265 (84200) UNEME-ENFERMEDADES 38 ENTRE AVENIDA 8 Y AVENIDA 9 NO. EXT. SIN NÚMERO NO. -

Otobius Megnini Infestations in Race Horses Rupika S

We are IntechOpen, the world’s leading publisher of Open Access books Built by scientists, for scientists 4,800 122,000 135M Open access books available International authors and editors Downloads Our authors are among the 154 TOP 1% 12.2% Countries delivered to most cited scientists Contributors from top 500 universities Selection of our books indexed in the Book Citation Index in Web of Science™ Core Collection (BKCI) Interested in publishing with us? Contact [email protected] Numbers displayed above are based on latest data collected. For more information visit www.intechopen.com Chapter Spinose Ear Tick Otobius megnini Infestations in Race Horses Rupika S. Rajakaruna and Chulantha Prasanga Diyes Abstract Spinose ear tick, Otobius megnini, has a worldwide distribution causing otoaca- riasis or parasitic otitis in animals and humans. It mainly infests horses and cattle. It is a nidicolous, one-host soft tick spread from the New World to the Old World and is now distributed across all the continents. Only the larvae and nymphs are parasitic, feeding inside the ear canal of the host for a long period. Adult males and females are free-living and nonfeeding, and mating occurs off the host. Being inside the ear canal of the host allows the tick to be distributed over a vast geographic region through the distribution of the host animals. The presence of infectious agents Coxiella burnetii, the agent of Q fever, spotted fever rickettsia, Ehrlichia canis, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Babesia in O. megnini has been reported, but its role as a vector has not been confirmed. -

Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. Nogales, Santa Cruz Co., Ariz

r 4111111111111110 41111111111110 111111111111111b Ube Land of 1 Nayarit I ‘11•1114111111n1111111111n IMO In Account of the Great Mineral Region South of the Gila Mt) er and East from the Gulf of California to the Sierra Madre Written by ALLEN T. BIRD Editor The Oasis, Nogales, Arizona Published under the Auspices of the RIZONA AND SONORA CHAMBER. OF MINES 1904 THE OASIS PRINTING HOUSE, INCORPORATED 843221 NOGALES, ARIZONA Arizona and Sonora Chamber of Mines, Nogales, Arizona. de Officers. J. McCALLUM, - - President. A. SANDOVAL, First Vice-President. F. F. CRANZ, Second Vice-President. BRACEY CURTIS, - Treasurer. N. K. STALEY, - - Secretary. .ss Executive Committee. THEO. GEBLER. A. L PELLEGRIN. A. L. LEWIS. F. PELTIER. CON CY/017E. COLBY N. THOMAS. F. F. CRANZ. N the Historia del Nayarit, being a description of "The Apostolic Labors of the Society of Jesus in North America," embracing particularly that portion surrounding the Gulf of California, from the Gila River on the north, and comprising all the region westward from the main summits of the Sierra Madre, which history was first published in Barcelona in 1754, and was written some years earlier by a member of the order, Father Jose Ortega, being a compilation of writings of other friars—Padre Kino, Padre Fernanda Coasag, and others—there appear many interesting accounts of rich mineral regions in the provinces described, the mines of which were then in operation, and had been during more than a century preceding, constantly pour- ing a great volume of metallic wealth into that flood of precious metals which Mexico sent across the Atlantic to enrich the royal treasury of imperial Spain and filled to bursting the capacious coffers of the Papacy. -

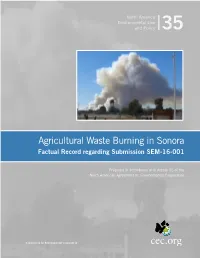

Agricultural Waste Burning in Sonora Factual Record Regarding Submission SEM-16-001

North America Environmental Law and Policy 35 Agricultural Waste Burning in Sonora Factual Record regarding Submission SEM-16-001 Prepared in accordance with Article 15 of the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation Commission for Environmental Cooperation Please cite as: CEC. 2014. Agricultural Waste Burning in Sonora. Factual Record regarding Submission SEM-16-001 . Montreal, Canada: Commission for Environmental Cooperation. 84 pp. This report was prepared by the Secretariat of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation’s Submission on Enforcement Matters Unit. The information contained herein does not necessarily reflect the views of the CEC, or the governments of Canada, Mexico or the United States of America. Reproduction of this document in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes may be made without special permission from the CEC Secretariat, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. The CEC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication or material that uses this document as a source. Except where otherwise noted, this work is protected under a Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-No Derivative Works License. © Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 2018 ISBN: 978-2-89700-251-0 Disponible en español – ISBN: 978-2-89700-252-7 Disponible en français – ISBN: 978-2-89700-253-4 Legal deposit—Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2018 Legal deposit—Library and Archives Canada, 2018 Publication Details Publication type: Factual Record Publication date: September 2018 Original language: Spanish Review and quality assurance procedures: Final Party review: From 28 February to 3 May 2018 For more information: Commission for Environmental Cooperation 393, rue St-Jacques Ouest, bureau 200 Montreal (Quebec) H2Y 1N9 Canada t 514.350.4300 f 514.350.4314 [email protected] / www.cec.org North America Environmental Law and Policy 35 Agricultural Waste Burning in Sonora Factual Record regarding Submission SEM-16-001 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 1. -

Response of the Tick Dermacentor Variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae) to Hemocoelic Inoculation of Borrelia Burgdorferi (Spirochetales) Robert Johns Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Biological Sciences Faculty Publications Biological Sciences 2000 Response of the Tick Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae) to Hemocoelic Inoculation of Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochetales) Robert Johns Old Dominion University Daniel E. Sonenshine Old Dominion University, [email protected] Wayne L. Hynes Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_fac_pubs Part of the Entomology Commons, and the Microbiology Commons Repository Citation Johns, Robert; Sonenshine, Daniel E.; and Hynes, Wayne L., "Response of the Tick Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae) to Hemocoelic Inoculation of Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochetales)" (2000). Biological Sciences Faculty Publications. 119. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_fac_pubs/119 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Journal of Medical Entomology Running Head: Control ofB. burgdorferi in D. variabilis. Send Proofs to: Dr. Daniel E. Sonenshine Department of Biological Sciences Old Dominion University Norfolk, Virginia 23529 Tel (757) 683 - 3612/ Fax (757) 683 - 52838 E-Mail [email protected] Control ofBorrelia burgdorferi (Spirochetales) Infection in the Tick Dennacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae). ROBERT JOHNS, DANIELE. SONENSHINE AND WAYNE L. HYNES Department ofBiological, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Vrrginia 23529 2 ABSTRACT. When Borre/ia burgdorferi B3 l low passage strain spirochetes are directly injected into the hemocoel ofDermacentor variabi/is females, the bacteria are cleared from the hemocoel within less than 24 hours. -

2019 Annual Report

Table of Contents A Message from the Chairman.............................................................. 1 A Message from the President .............................................................. 3 Our Impact .................................................................................... 4 What’s Unique About Sister Cities International?....................................... 5 Global Leaders Circle............................................................................... 6 2018 Activities....................................................................................... 7 Where We Are (Partnership Maps) ........................................................ 14 Membership with Sister Cities International ........................................... 18 Looking for a Sister City Partner?......................................................... 19 Membership Resources and Discounts ................................................. 20 Youth Leadership Programs ............................................................... 21 YAAS 2018 Winners & Finalists ............................................................ 23 2018 Youth Leadership Summit .......................................................... 24 Sister Cities International’s 2018 Annual Conference in Aurora, Colorado.......................................................................... 26 Annual Awards Program Winners......................................................... 27 Special Education and Virtual Learning in the United States and Palestine (SEVLUP) -

![Tick [Genome Mapping]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3561/tick-genome-mapping-753561.webp)

Tick [Genome Mapping]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Public Health Resources Public Health Resources 2008 Tick [Genome Mapping] Amy J. Ullmann Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, CO Jeffrey J. Stuart Purdue University, [email protected] Catherine A. Hill Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/publichealthresources Part of the Public Health Commons Ullmann, Amy J.; Stuart, Jeffrey J.; and Hill, Catherine A., "Tick [Genome Mapping]" (2008). Public Health Resources. 108. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/publichealthresources/108 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Public Health Resources at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Health Resources by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 8 Tick Amy J. Ullmannl, Jeffrey J. stuart2, and Catherine A. Hill2 Division of Vector Borne-Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, CO 80521, USA Department of Entomology, Purdue University, 901 West State Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA e-mail:[email protected] 8.1 8.1 .I Introduction Phylogeny and Evolution of the lxodida Ticks and mites are members of the subclass Acari Ticks (subphylum Chelicerata: class Arachnida: sub- within the subphylum Chelicerata. The chelicerate lin- class Acari: superorder Parasitiformes: order Ixodi- eage is thought to be ancient, having diverged from dae) are obligate blood-feeding ectoparasites of global Trilobites during the Cambrian explosion (Brusca and medical and veterinary importance. Ticks live on all Brusca 1990). It is estimated that is has been ap- continents of the world (Steen et al. -

Sonora, Mexico

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development SONORA, MEXICO, Sonora is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico and has made great strides in Sonora, building its human capital and skills. How can Sonora turn the potential of its universities and technological institutions into an active asset for economic and Mexico social development? How can it improve the equity, quality and relevance of education at all levels? Jaana Puukka, Susan Christopherson, This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional Patrick Dubarle, Jocelyne Gacel-Ávila, reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. Sonora, Mexico CONTENTS Chapter 1. Human capital development, labour market and skills Chapter 2. Research, development and innovation Chapter 3. Social, cultural and environmental development Chapter 4. Globalisation and internationalisation Chapter 5. Capacity building for regional development ISBN 978- 92-64-19333-8 89 2013 01 1E1 Higher Education in Regional and City Development: Sonora, Mexico 2013 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PRELIMINARY DEPOSIT-TYPE MAP of NORTHWESTERN MEXICO by Kenneth R

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PRELIMINARY DEPOSIT-TYPE MAP OF NORTHWESTERN MEXICO By Kenneth R. Leonard U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 89-158 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Any use of trade, product, firm, or industry names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Menlo Park, CA 1989 Table of Contents Page Introduction..................................................................................................... i Explanation of Data Fields.......................................................................... i-vi Table 1 Size Categories for Deposits....................................................................... vii References.................................................................................................... viii-xx Site Descriptions........................................................................................... 1-330 Appendix I List of Deposits Sorted by Deposit Type.............................................. A-1 to A-22 Appendix n Site Name Index...................................................................................... B-1 to B-10 Plate 1 Distribution of Mineral Deposits in Northwestern Mexico Insets: Figure 1. Los Gavilanes Tungsten District Figure 2. El Antimonio District Figure 3. Magdalena District Figure 4. Cananea District Preliminary Deposit-Type Map of -

Dermacentor Albipictus) in Two Regenerating Forest Habitats in New Hampshire, Usa

ABUNDANCE OF WINTER TICKS (DERMACENTOR ALBIPICTUS) IN TWO REGENERATING FOREST HABITATS IN NEW HAMPSHIRE, USA Brent I. Powers and Peter J. Pekins Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824, USA. ABSTRACT: Recent decline in New Hampshire’s moose (Alces alces) population is attributed to sus- tained parasitism by winter ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) causing high calf mortality and reduced productivity. Location of larval winter ticks that infest moose is dictated by where adult female ticks drop from moose in April when moose preferentially forage in early regenerating forest in the northeast- ern United States. The primary objectives of this study were to: 1) measure and compare larval abun- dance in 2 types of regenerating forest (clear-cuts and partial harvest cuts), 2) measure and compare larval abundance on 2 transect types (random and high-use) within clear-cuts and partial harvests, and 3) identify the date and environmental characteristics associated with termination of larval questing. Larvae were collected on 50.5% of 589 transects; 57.5% of transects in clear-cuts and 44.3% in partial cuts. The average abundance ranged from 0.11–0.36 ticks/m2 with abundance highest (P < 0.05) in partial cuts and on high-use transects in both cut types over a 9-week period; abundance was ~2 × higher during the principal 6-week questing period prior to the first snowfall. Abundance (collection rate) was stable until the onset of < 0°C and initial snow cover (~15 cm) in late October, after which collection rose temporarily on high-use transects in partial harvests during a brief warm-up.