Notes on the Palms of Guinea-Bissau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Fur Harvester Digest 3 SEASON DATES and BAG LIMITS

2021 Michigan Fur Harvester Digest RAP (Report All Poaching): Call or Text (800) 292-7800 Michigan.gov/Trapping Table of Contents Furbearer Management ...................................................................3 Season Dates and Bag Limits ..........................................................4 License Types and Fees ....................................................................6 License Types and Fees by Age .......................................................6 Purchasing a License .......................................................................6 Apprentice & Youth Hunting .............................................................9 Fur Harvester License .....................................................................10 Kill Tags, Registration, and Incidental Catch .................................11 When and Where to Hunt/Trap ...................................................... 14 Hunting Hours and Zone Boundaries .............................................14 Hunting and Trapping on Public Land ............................................18 Safety Zones, Right-of-Ways, Waterways .......................................20 Hunting and Trapping on Private Land ...........................................20 Equipment and Fur Harvester Rules ............................................. 21 Use of Bait When Hunting and Trapping ........................................21 Hunting with Dogs ...........................................................................21 Equipment Regulations ...................................................................22 -

Karwar, Close to the National Highway 17 (NH-17)

E421 VOL. 9 Wilsol In association with Public Disclosure Authorized IJiE IIIE Phase II - Environment Assessment Report for the Segment of Corridor 13A which passes through Dandeli Wildlife and Anshi National Park Public Disclosure Authorized Project Co-ordinating Consultancy Services (PCC) For the Karnataka State Highways Improvement Project IBRD Loan/Credit No. LN-4114 Belga Wi~~~~~dar Public Disclosure Authorized Karwa.r Mangalor, -g)alore Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared for Gov, of Karnataka Pubi c Works Dept. (PIU,KSHIP) Jqnuary 2005 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Karnataka State Highways Environnmental Assessment Reportfor the Segmenit of Improvement Project Corridorl3A which passes tlroughi Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary and Anshi National Park EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Introduction Corridor 13A, also known as State Highway 95 (SH 95), commences at Ramanagar junction on NH-4A near Londa in Belgaum District, enters Uttarakannada District and ends at Sadashivgadh, near Karwar, close to the National Highway 17 (NH-17). The total length of this Corridor is 121 Km and it offers c onnectivity to Belgaum, Karwar and Goa. This corridor passes through the Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary and Anshi National Park. Corridor 13A has been selected for rehabilitation under the Kamataka State Highways Improvement Project (KSHIP). 2. Project Road A 28 km section of Corridor 13A i.e from chainage 55.57 Km to 83.41 Km, passes through the Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary and the Anshi National Park. The corridor traverses buffer and core zones w ith undulating and hilly terrain t hroughout its e ntire length. T he width o f t he e xisting carriageway varies from 3.75m to 5.5m. -

Fur, Skin, and Ear Mites (Acariasis)

technical sheet Fur, Skin, and Ear Mites (Acariasis) Classification flank. Animals with mite infestations have varying clinical External parasites signs ranging from none to mild alopecia to severe pruritus and ulcerative dermatitis. Signs tend to worsen Family as the animals age, but individual animals or strains may be more or less sensitive to clinical signs related Arachnida to infestation. Mite infestations are often asymptomatic, but may be pruritic, and animals may damage their skin Affected species by scratching. Damaged skin may become secondarily There are many species of mites that may affect the infected, leading to or worsening ulcerative dermatitis. species listed below. The list below illustrates the most Nude or hairless animals are not susceptible to fur mite commonly found mites, although other mites may be infestations. found. Humans are not subject to more than transient • Mice: Myocoptes musculinus, Myobia musculi, infestations with any of the above organisms, except Radfordia affinis for O. bacoti. Transient infestations by rodent mites may • Rats: Ornithonyssus bacoti*, Radfordia ensifera cause the formation of itchy, red, raised skin nodules. Since O. bacoti is indiscriminate in its feeding, it will • Guinea pigs: Chirodiscoides caviae, Trixacarus caviae* infest humans and may carry several blood-borne • Hamsters: Demodex aurati, Demodex criceti diseases from infected rats. Animals with O. bacoti • Gerbils: (very rare) infestations should be treated with caution. • Rabbits: Cheyletiella parasitivorax*, Psoroptes cuniculi Diagnosis * Zoonotic agents Fur mites are visible on the fur using stereomicroscopy and are commonly diagnosed by direct examination of Frequency the pelt or, with much less sensitivity, by examination Rare in laboratory guinea pigs and gerbils. -

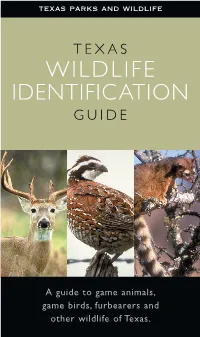

Texas Wildlife Identification Guide: a Guide to Game Animals, Game

texas parks and wildlife TEXAS WILDLIFE IDENTIFICATION GUIDE A guide to game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife of Texas. INTRODUCTION TEXAS game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife are important for many reasons. They provide countless hours of viewing and recreational opportunities.They benefit the Texas economy through hunting and “nature tourism” such as birdwatching. Commercial businesses that provide birdseed, dry corn and native landscaping may be devoted solely to attracting many of the animals found in this book. Local hunting and trapping economies, guiding operations and hunting leases have prospered because of the abun- dance of these animals in Texas.The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department benefits because of hunting license sales, but it uses these funds to research, manage and pro- tect all wildlife populations – not just game animals. Game animals provide humans with cultural, social, aesthetic and spiritual pleasures found in wildlife art, taxi- dermy and historical artifacts. Conservation organizations dedicated to individual species such as quail, turkey and deer, have funded thousands of wildlife projects throughout North America, demonstrating the mystique game animals have on people. Animals referenced in this pocket guide exist because their habitat exists in Texas. Habitat is food, cover, water and space, all suitably arranged.They are part of a vast food chain or web that includes thousands more species of wildlife such as the insects, non-game animals, fish and i rare/endangered species. Active management of wild landscapes is the primary means to continue having abundant populations of wildlife in Texas. Preservation of rare and endangered habitat is one way of saving some species of wildlife such as the migratory whooping crane that makes Texas its home in the winter. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

ECOSYSTEM SERVICES OF PTEROPODID BATS, WITH SPECIAL ATTENTION TO FLYING FOXES (PTEROPUS AND ACERODON) IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA By SHEHERAZADE A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Sheherazade To my mom Thank you for teaching me how to be an independent, strong, and happy woman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Holly Ober, for her guidance and patience during my study. I thank her for always encouraging me to maximize all learning opportunities to gain skills and knowledge that will be important for my future. I thank Dr. Bette Loiselle and Dr. Todd Palmer for their invaluable advice to this study and thesis. I thank the Center for International Forestry and United States Agency for International Development for funding my master program. I thank Dr. Steven Lawry, Ms. Dina Hubuddin, Ms. Rahayu Koesnadi, Ms. Raya Soendjoto, Dr. Karen Kainer, and Dr. Bette Loiselle for providing supports and managing administrative issues during my entire study. I thank Tropical Conservation and Development (TCD) University of Florida for allowing me to learn about the interdisciplinary aspects of conservation and awarding me a field research grant. I thank Rufford Small Grant, Bat Conservation International, and IdeaWild for also funding my research. I thank Government Agency of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries of Central Sulawesi, Integrated Permit Service Agency of Central and West Sulawesi, Longkoga Barat/Timur village, Bualemo Subdistrict, Batetangnga village and Binuang Subdistrict for permits. I thank Alliance for Tompotika Conservation and my team for their tremendous assistance in the field. -

• 5 Plants- Skunk Cabbage, Sassafras Tree, Cross Vine, Royal Fern, Trumpet

5 plants- skunk cabbage, sassafras tree, cross vine, royal fern, trumpet vine 5 insects/ arachnids- six-spotted fishing spider, green darner dragon fly, ground beetle, mud dauber, black swallowtail caterpillar 3 reptiles or amphibians- Eastern river cooter, marbled salamander, Fowler’s toad 3 fish- longear sunfish, walleye, smallmouth bass 3 water birds- king fisher, egret, blue heron 2 raptors- red-shouldered hawk, great-horned owl 3 small mammals- muskrat, Elliot’s short-tailed shrew, Eastern cottontail rabbit 2 medium mammals- mink, raccoon 2 large mammals- black bears, white-tailed deer 3 decomposers- fungus, white- nosed fungus syndrome, morel mushroom, pill bug 3 non-living components Skunk cabbage is a perennial wildflower that grows in swampy, wet areas of forest lands. This unusual plant sprouts very early in the spring, and has an odd chemistry that creates its own heat, often melting the snow around itself as it first sprouts in the spring. While the first sprout, a pod-like growth, looks like something out of a science-fiction movie, the skunk cabbage is a plain-looking green plant once the leaves appear. You may find two common types: Eastern skunk cabbage, which is purple, and Western skunk cabbage, which is yellow. Skunk cabbage gets its name from the fact that, when the leaves are crushed or bruised, it gives off a smell of skunk or rotting meat. Skunk cabbage is eaten by wood ducks, honey bees, and the eastern forest snail. The sassafras tree is known for its brilliant display of autumn foliage and aromatic smell. The species are unusual in having three distinct leaf patterns on the same plant: unlobed oval, bilobed (mitten-shaped), and trilobed (three-pronged). -

Zoey and Sassafras Covers a Glowing Photo and Learns an Like

Family Activities Who is Zoey? Design and experiment like Zoey to figure out In the first book of this series, Zoey dis- what a bug you may find outside would look Zoey and Sassafras covers a glowing photo and learns an like. Make sure that an adult helps you and that your bug can breathe, is kept out of direct sun- amazing secret. Injured magical animals light and has access to water. After a few hours come to their backyard barn for help! Dragons & Marshmallows of observing your bug, release it back into the When a sick baby dragon appears, it’s up wild. to Zoey and Sassafras to figure out what’s wrong using the scientific method. Will Can you think of another magical creature that Zoey might encounter? Draw a picture of your they be able to help little Marshmallow magical creature. Then write or verbally ex- before it’s too late? Little Rock School District staff who plain what the creature is like and what it needs _____________________________ help with. Start a science journal just like Zoey helped with the creation of the guide in- after drawing your magical creature. Be sure to clude: include a drawing of your creature and all the The Case for STEM Education parts to the experiment of what your creature Joel Spencer needs help with (question, hypothesis, materi- “60% of U.S. employers are having difficulties als, steps to the experiment and conclusion). finding qualified workers to fill STEM va- Laura Beth Arnold cancies.” - Council of Foreign elations _________________________________ Nolan Brown What is the scientific method? “54% percent of the nation’s 4th graders Margaret Wang and 47% of its 8th graders report that The scientific method is a way to ask and they “never or hardly ever” write re- Sabrina Stout answer scientific questions by making ob- ports about science projects. -

Nutrition of Fur Animals

NUTRITION OF FUR ANIMALS by Charles E. Kellogg ^ SILVER FOXES, minks, and rabbits are now being raised as part-time enterprises on a considerable number of farms, and some producers are in the business on a large scale. There is also some interest in the raising of martens and fishers. Here is a summary of the scientific work—not yet very extensive—that has been done on the feeding of of these animals, with special emphasis on its practical application. THE ONLY FUR ANIMALS that are now being raised commercially to any great extent are silver foxes and minks. Martens and fishers also have commercial possibilities if satisfactory reproduction can be obtained in captivity. Attempts have been made at one time or -another, largely through the efforts of propagandists, to ''ranch-raise'' skunks, badgers, raccoons, beavers, and muskrats for their fur, but the undertakings were not profitable because the cost of feeding and other costs of production exceeded the market quotations on similar wild-caught skins. A striking mutation may develop in some of these species, however, which will produce an animal with new^ characteris- tics that will make production in captivity remunerative. Natural selection in the wild, where matings are promiscuous, fosters the survival of those animals best fitted to live under rigorous conditions. The survival of fur animals in captivity, where matings can be controlled, is dependent upon their ability^ to produce beautiful pelts economically under more or less pampered conditions, rather than upon adaptation to rigorous competitive living. The profitable t^^pe is the docile, tractable, easily kept animal that responds to care without putting on excess fat and becoming sluggish and nonproduc- tive. -

Report B. E. Fernow

U S DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE REPORT OF TIlE CHIEF OF THE DIVISION OF FORESTRY FOIl 1 8t, () . DY B. E. FERNOW. EROM THE REPORT OF THE SECRETARY OF AGRICULTURE FOR 1C2. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1893. CONTENTS. Page. THE WORK OF THE YEAR 294-302 Bulletin on timber physics published and favorably received, 294; in- creased value of Southern pine resulting from our investigations of the turpentine industry, 295; inquiry begun as to the tannin con- tents of certain woods, 296; revision of the nomenclature of our trees, 297; distribution of seeds and seedlings; forest-planting ex- periment, 298; preparation of exhibit for the World's Fair, 301; present situation of the division, 302. GENERAL CoNDITION or FOREST AREAS 303-313 Extent of forests at discovery of the continent, 302; causel of the re- duction in forest areas, 303value of exports of forest products during thirty years, value of forest products used in 1860, 1870, and 1880, 304; number, distribution, and capacity of sawmills, 305; aver- age prices of lumber anti stumpage for thirty years, 307; forest fires, 308; proposed act for protection of forests from fires, 310; present extent of forest area, 312; public and private ownership Of forests, Government forest reservations, 313. THE FORESTRY MOVEMENT 315-318 Present condition of the Arbor Day movement, 316; memorial of the A A. A. S. to Congress, appointment of Dr. Hongh to report on forestry, establishment of the Division of Forestry, organization of Ameri- can Forestry Congress, State forestry associations and commissions, 317; forest reservations made by proclamation of the President, 318. -

Chapter W-3 - Furbearers and Small Game, Except Migratory Birds

09/01/2021 CHAPTER W-3 - FURBEARERS AND SMALL GAME, EXCEPT MIGRATORY BIRDS Index Page ARTICLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS #300 Definitions 1 #301 License Fees 1 #302 Hours 2 #303 Manner of Take 2 #304 License Requirements 5 #305 Evidence of Sex/Species 5 ARTICLE II SMALL GAME SEASON DATES, UNITS (AS DESCRIBED IN CHAPTER O OF THESE REGULATIONS), BAG AND POSSESSION LIMITS, LIMITED LICENSES AND PERMITS #306 Cottontail Rabbit, Snowshoe Hare, White-tailed & Black-tailed 6 jackrabbit #307 Abert's Squirrels 6 #308 Fox Squirrel and Pine Squirrels 6 #309 Wyoming (Richardson's) ground squirrel, black-tailed, white-tailed, 6 and Gunnison prairie dogs #310 Common Snapping Turtle 7 #311 Marmot 7 #312 Prairie Rattlesnake 7 #313 Dusky (Blue) Grouse 7 #314 White-tailed Ptarmigan 7 #315 Greater Sage-grouse 8 #316 Gunnison Sage-grouse 8 #317 Mountain Sharp-tailed Grouse 8 #318 Chukar Partridge 9 #319 Pheasant 9 #320 Quail (Northern Bobwhite, Scaled, Gambel's) 9 #321 Greater Prairie-Chicken 9 #322 Wild Turkey 10 #322.5 Ranching for Wildlife - Turkey 17 #323 Mink, pine marten, badger, gray fox, red fox, swift fox, raccoon, 20 ring-tailed cat, striped skunk, western spotted skunk, long-tailed weasel, short-tailed weasel, opossum and muskrat #324 Bobcat 20 #325 Coyote 20 #326 Beaver 20 Basis and Purpose 22 Statement CHAPTER W-3 - FURBEARERS and SMALL GAME, EXCEPT MIGRATORY BIRDS ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS #300 - Definitions A. "Canada Lynx Recovery Area" means the area of the San Juan and Rio Grande National Forests and associated lands above 9,000 feet extending west from a north-south line passing through Del Norte and east from a north-south line passing through Dolores and from the New Mexico state line north to the Gunnison basin (including Taylor Park east to the Collegiate Range). -

Naval Stores: the Industry

286 NAVAL STORES: THE INDUSTRY JAY WARD Naval stores arc the derivatives of an ark of gopher wood; rooms shalt the crude gum—oleoresin—that comes thou make in the ark, and shalt pitch from living pine trees, pine stumps, it wdthin and without with pitch." and dead lightwood. Some arc byprod- When Columbus discovered Amer- ucts from sulfate pulp mills. The term ica, the center of production in Europe is limited generally to turpentine and extended from Scandinavia through rosin, but it can be said to cover pine the Baltic countries. From them came tar, pine oil, and rosin oils. In the trade, quantities of tar and pitch for use by the product from living pine trees is the fleets of wooden sailing vessels of known as gum naval stores; the prod- all the European nations. King Phillip uct from stumps, lightwood, and pulp of Spain drew from this source for mills is called wood naval stores. In his Spanish Armada. Queen Elizabeth Colonial days, gum was cooked down drew from it for her British fleet. One to a thick tar and used to preserve the of the basic commodities sought by the ropes and calk the seams of the ships— Europeans in the New World w^as a and from that we got the name "naval source of naval stores for their ships. stores" for the products used now in a Turpentining is one of the oldest hundred ways unconnected with ships. and most picturesque of American in- The gum naval stores industry, at its dustries. The production of tar, pitch, peak in 1908-9, produced 750,000 bar- rosin, and turpentine started when rels (50 gallons each) of gum spirits of the first settlers landed on the Atlan- turpentine and 1,998,400 drums of gum tic coast. -

Carson Naval Stores Company

} AND JOURNAL OF TRADE EN NB A WEEKLY PAPER FOR NAVAL STORES PRODUCERS, FACTORS, EXPORTERS AND ‘DEALERS, MANUFACTURERS OF SOAPS, VARNISHES, PAPER, PRINTING INKS, ETC. ea Vor. XXXII, No. 13 SAVANNAH, GA., SATURDAY, JUNE 24, 1922 Price $5.00 PER ANNUM Le J INININININININ INN TN ININTINININININININT NINININININ IN IN IN IN IN IN IN IN IN ININ INAS IN mate < GN J. A. G. CARSON, President H. L. KAYTON, Vice-President J. A. G. CARSON, Jr., Vice-President W. H. BARBER CO. C. H. CARSON, Vice-President at Jacksonville 3650 SOUTH HOMAN AVENUE Sr Carson CHICAGO, ILL. Rosin, Turpentine Naval Stores Company Pine Oil, Ete. Organized in 1879. Oldest House in the Business. DIRECT SHIPMENT FROM SOUTH. BUYERS, FACTORS IT WILL PAY YOU TO SECURE OUR PRICES. PRODUCERS,PLACE YOUR OFFERS WITH US. AND WHOLESALE GROCERS PRINCIPAL OFFICE BRANCH OFFICE SAVANNAH, GEORGIA JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA SALES DEPARTMENT National Bank Building Atlantic National Bank Building Gillican-Chipley With an organization unsurpassed and ample means at our command, our facilities for handling your business are second to none Company, Inc. WE INVITE YOUR CORRESPONDENCE | NEW ORLEANS, LA. A Suggestion! eee Good Business Policy demands COMPANY ie. NEW ORLEANS, LA. US.A. (GED PURE GUM TURPENTIN} that you buy your Rosin and Turpentine from Reliable Firms PRODUCERS, DEALERS AND EXPORTERS So Columbia Naval Stores Co. Savannah, Georgia Rosin—Turpentine » : : 2 SAVANNAH WEEKLY NAVAL STORES REVIEW AND JOURNAL OF TRADE ~~ JOHN E. HARRIS, President JOHN H. POWELL, Vice-President H. L. RICHMOND, Vice-President D. M. FLYNN, Vice-President ; L. M. POWELL, Secretary-Treasurer Flynn-Harris-Bullard Co.