The Use of the Eight-Year Cycle in the Early Malay Calendar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mathematics of the Chinese, Indian, Islamic and Gregorian Calendars

Heavenly Mathematics: The Mathematics of the Chinese, Indian, Islamic and Gregorian Calendars Helmer Aslaksen Department of Mathematics National University of Singapore [email protected] www.math.nus.edu.sg/aslaksen/ www.chinesecalendar.net 1 Public Holidays There are 11 public holidays in Singapore. Three of them are secular. 1. New Year’s Day 2. Labour Day 3. National Day The remaining eight cultural, racial or reli- gious holidays consist of two Chinese, two Muslim, two Indian and two Christian. 2 Cultural, Racial or Religious Holidays 1. Chinese New Year and day after 2. Good Friday 3. Vesak Day 4. Deepavali 5. Christmas Day 6. Hari Raya Puasa 7. Hari Raya Haji Listed in order, except for the Muslim hol- idays, which can occur anytime during the year. Christmas Day falls on a fixed date, but all the others move. 3 A Quick Course in Astronomy The Earth revolves counterclockwise around the Sun in an elliptical orbit. The Earth ro- tates counterclockwise around an axis that is tilted 23.5 degrees. March equinox June December solstice solstice September equinox E E N S N S W W June equi Dec June equi Dec sol sol sol sol Beijing Singapore In the northern hemisphere, the day will be longest at the June solstice and shortest at the December solstice. At the two equinoxes day and night will be equally long. The equi- noxes and solstices are called the seasonal markers. 4 The Year The tropical year (or solar year) is the time from one March equinox to the next. The mean value is 365.2422 days. -

Islamic Calendar from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Islamic calendar From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia -at اﻟﺘﻘﻮﻳﻢ اﻟﻬﺠﺮي :The Islamic, Muslim, or Hijri calendar (Arabic taqwīm al-hijrī) is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 months in a year of 354 or 355 days. It is used (often alongside the Gregorian calendar) to date events in many Muslim countries. It is also used by Muslims to determine the proper days of Islamic holidays and rituals, such as the annual period of fasting and the proper time for the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Islamic calendar employs the Hijri era whose epoch was Islamic Calendar stamp issued at King retrospectively established as the Islamic New Year of AD 622. During Khaled airport (10 Rajab 1428 / 24 July that year, Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to 2007) Yathrib (now Medina) and established the first Muslim community (ummah), an event commemorated as the Hijra. In the West, dates in this era are usually denoted AH (Latin: Anno Hegirae, "in the year of the Hijra") in parallel with the Christian (AD) and Jewish eras (AM). In Muslim countries, it is also sometimes denoted as H[1] from its Arabic form ( [In English, years prior to the Hijra are reckoned as BH ("Before the Hijra").[2 .(ﻫـ abbreviated , َﺳﻨﺔ ﻫِ ْﺠﺮﻳّﺔ The current Islamic year is 1438 AH. In the Gregorian calendar, 1438 AH runs from approximately 3 October 2016 to 21 September 2017.[3] Contents 1 Months 1.1 Length of months 2 Days of the week 3 History 3.1 Pre-Islamic calendar 3.2 Prohibiting Nasī’ 4 Year numbering 5 Astronomical considerations 6 Theological considerations 7 Astronomical -

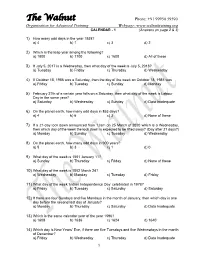

CALENDAR - 1 (Answers on Page 2 & 3)

The Walnut Phone: +91 99950 59590 Organisation for Advanced Training Webpage: www.walnuttraining.org CALENDAR - 1 (Answers on page 2 & 3) 1) How many odd days in the year 1938? a) 4 b) 1 c) 3 d) 2 2) Which is the leap year among the following? a) 1800 b) 1100 c) 1600 d) All of these 3) If July 5, 2017 is a Wednesday, then what day of the week is July 5, 2018? a) Tuesday b) Friday c) Thursday d) Wednesday 4) If October 18, 1986 was a Saturday, then the day of the week on October 18, 1985 was a) Friday b) Tuesday c) Sunday d) Monday 5) February 27th of a certain year falls on a Saturday, then what day of the week is Labour Day in the same year? a) Saturday b) Wednesday c) Sunday d) Data Inadequate 6) On the planet earth, how many odd days in 853 days? a) 4 b) 6 c) 3 d) None of these 7) If a 21-day lock down announced from 12am on 25 March of 2020 which is a Wednesday, then which day of the week the lock down is expected to be lifted away? (Day after 21 days?) a) Monday b) Sunday c) Tuesday d) Wednesday 8) On the planet earth, how many odd days in 900 years? a) 5 b) 3 c) 1 d) 0 9) What day of the week is 1501 January 11? a) Sunday b) Thursday c) Friday d) None of these 10) What day of the week is 1802 March 24? a) Wednesday b) Monday c) Tuesday d) Friday 11) What day of the week ‘Indian Independence Day’ celebrated in 1978? a) Friday b) Tuesday c) Saturday d) Saturday 12) If there are four Sundays and five Mondays in the month of January, then which day is one day before the second last day of January? a) Monday b) Thursday c) Saturday d) Data Inadequate 13) Which is the same calendar year of the year 1596? a) 1608 b) 1636 c) 1624 d) 1640 14) Which day is New Years’ Eve, if there are five Tuesdays and five Wednesdays in the month of December? a) Friday b) Wednesday c) Thursday d) Data Inadequate 1 The Walnut Phone: +91 99950 59590 Organisation for Advanced Training Webpage: www.walnuttraining.org Basic facts of calendars (Answers next page): 1) Odd Days Number of days more than the complete weeks, are called odd days in a given period. -

How Long Is a Year.Pdf

How Long Is A Year? Dr. Bryan Mendez Space Sciences Laboratory UC Berkeley Keeping Time The basic unit of time is a Day. Different starting points: • Sunrise, • Noon, • Sunset, • Midnight tied to the Sun’s motion. Universal Time uses midnight as the starting point of a day. Length: sunrise to sunrise, sunset to sunset? Day Noon to noon – The seasonal motion of the Sun changes its rise and set times, so sunrise to sunrise would be a variable measure. Noon to noon is far more constant. Noon: time of the Sun’s transit of the meridian Stellarium View and measure a day Day Aday is caused by Earth’s motion: spinning on an axis and orbiting around the Sun. Earth’s spin is very regular (daily variations on the order of a few milliseconds, due to internal rearrangement of Earth’s mass and external gravitational forces primarily from the Moon and Sun). Synodic Day Noon to noon = synodic or solar day (point 1 to 3). This is not the time for one complete spin of Earth (1 to 2). Because Earth also orbits at the same time as it is spinning, it takes a little extra time for the Sun to come back to noon after one complete spin. Because the orbit is elliptical, when Earth is closest to the Sun it is moving faster, and it takes longer to bring the Sun back around to noon. When Earth is farther it moves slower and it takes less time to rotate the Sun back to noon. Mean Solar Day is an average of the amount time it takes to go from noon to noon throughout an orbit = 24 Hours Real solar day varies by up to 30 seconds depending on the time of year. -

M a Late-11Th-Century Copy of Ibn Comes to Us from the Middle East and Central and Inner Asia

ARAMCOWORLD.COMARAMC O W O RLD.C O M MAPS 2020 1441–1442 GREGORIAN HIJRI shows how the Nile emerges from the mythical Mountains of the Moon (now Ethiopia), flows through multiple cataracts and heads north, crosses the equator to pass through the lands of Nubia, Aswan and Beja toward Fustat (medieval Cairo) and finishes in the Nile Delta near Dumyat (Damietta), where it empties into the Mediterranean Sea. Cartographers replicated this depiction of the Nile in various ways in every cartographic manuscript thereafter for centuries. As copies proliferated throughout the medieval Islamic Middle East, this helped establish what became, in effect, the world’s first geographical atlas series. Introduction and calendar captions by KAREN C. PINTO The maps pictured for the months of May and August are by different authors from that “Islamic atlas series” spawned by al-Khwarizmi. May shows the exceptional, three-folio map The richest–surviving heritage of premodern maps of the world of the Mediterranean Sea from a late-11th-century copy of Ibn comes to us from the Middle East and Central and Inner Asia. Hawqal’s Kitab surat al-‘ard. It is the earliest-known copy of the most-mimetic map of the Mediterranean. On it one can see the outlines of the Iberian Peninsula, the Calabrian Peninsula, the Al-Khwarizmi’s rom the Babylonian clay tablet of 600 bce to Katip as the Bahr al-Muhit (Encircling Ocean), which was the most Peloponnese, Constantinople, the map of the Nile Çelebi’s map of Japan drawn in 1732, geographers and basic marker of world maps up through medieval periods. -

The Central Islamic Lands

77 THEME The Central Islamic 4 Lands AS we enter the twenty-first century, there are over 1 billion Muslims living in all parts of the world. They are citizens of different nations, speak different languages, and dress differently. The processes by which they became Muslims were varied, and so were the circumstances in which they went their separate ways. Yet, the Islamic community has its roots in a more unified past which unfolded roughly 1,400 years ago in the Arabian peninsula. In this chapter we are going to read about the rise of Islam and its expansion over a vast territory extending from Egypt to Afghanistan, the core area of Islamic civilisation from 600 to 1200. In these centuries, Islamic society exhibited multiple political and cultural patterns. The term Islamic is used here not only in its purely religious sense but also for the overall society and culture historically associated with Islam. In this society not everything that was happening originated directly from religion, but it took place in a society where Muslims and their faith were recognised as socially dominant. Non-Muslims always formed an integral, if subordinate, part of this society as did Jews in Christendom. Our understanding of the history of the central Islamic lands between 600 and 1200 is based on chronicles or tawarikh (which narrate events in order of time) and semi-historical works, such as biographies (sira), records of the sayings and doings of the Prophet (hadith) and commentaries on the Quran (tafsir). The material from which these works were produced was a large collection of eyewitness reports (akhbar) transmitted over a period of time either orally or on paper. -

Package 'Lubridate'

Package ‘lubridate’ February 26, 2021 Type Package Title Make Dealing with Dates a Little Easier Version 1.7.10 Maintainer Vitalie Spinu <[email protected]> Description Functions to work with date-times and time-spans: fast and user friendly parsing of date-time data, extraction and updating of components of a date-time (years, months, days, hours, minutes, and seconds), algebraic manipulation on date-time and time-span objects. The 'lubridate' package has a consistent and memorable syntax that makes working with dates easy and fun. Parts of the 'CCTZ' source code, released under the Apache 2.0 License, are included in this package. See <https://github.com/google/cctz> for more details. License GPL (>= 2) URL https://lubridate.tidyverse.org, https://github.com/tidyverse/lubridate BugReports https://github.com/tidyverse/lubridate/issues Depends methods, R (>= 3.2) Imports generics, Rcpp (>= 0.12.13) Suggests covr, knitr, testthat (>= 2.1.0), vctrs (>= 0.3.0), rmarkdown Enhances chron, timeDate, tis, zoo LinkingTo Rcpp VignetteBuilder knitr Encoding UTF-8 LazyData true RoxygenNote 7.1.1 SystemRequirements A system with zoneinfo data (e.g. /usr/share/zoneinfo) as well as a recent-enough C++11 compiler (such as g++-4.8 or later). On Windows the zoneinfo included with R is used. 1 2 R topics documented: Collate 'Dates.r' 'POSIXt.r' 'RcppExports.R' 'util.r' 'parse.r' 'timespans.r' 'intervals.r' 'difftimes.r' 'durations.r' 'periods.r' 'accessors-date.R' 'accessors-day.r' 'accessors-dst.r' 'accessors-hour.r' 'accessors-minute.r' 'accessors-month.r' -

Calendars Tell History : Social Rhythm and Social Change in Rural Pakistan.', History and Anthropology., 25 (5)

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 20 November 2014 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Mughal, M. A. Z. (2014) 'Calendars tell history : social rhythm and social change in rural Pakistan.', History and anthropology., 25 (5). pp. 592-613. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2014.930034 Publisher's copyright statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor Francis Group in History and Anthropology on 18/06/2014, available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/02757206.2014.930034. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Calendars Tell History: Social Rhythm and Social Change in Rural Pakistan Muhammad Aurang Zeb Mughal Durham University Abstract Time is an important element of social organization. The temporal models such as the calendar provide social rhythm by regulating various activities. -

In Interdisciplinary Studies of Climate and History

PERSPECTIVE Theimportanceof“year zero” in interdisciplinary studies of climate and history PERSPECTIVE Ulf Büntgena,b,c,d,1,2 and Clive Oppenheimera,e,1,2 Edited by Jean Jouzel, Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de L’Environ, Orme des Merisiers, France, and approved October 21, 2020 (received for review August 28, 2020) The mathematical aberration of the Gregorian chronology’s missing “year zero” retains enduring potential to sow confusion in studies of paleoclimatology and environmental ancient history. The possibility of dating error is especially high when pre-Common Era proxy evidence from tree rings, ice cores, radiocar- bon dates, and documentary sources is integrated. This calls for renewed vigilance, with systematic ref- erence to astronomical time (including year zero) or, at the very least, clarification of the dating scheme(s) employed in individual studies. paleoclimate | year zero | climate reconstructions | dating precision | geoscience The harmonization of astronomical and civil calendars have still not collectively agreed on a calendrical in the depths of human history likely emerged from convention, nor, more generally, is there standardi- the significance of the seasonal cycle for hunting and zation of epochs within and between communities and gathering, agriculture, and navigation. But difficulties disciplines. Ice core specialists and astronomers use arose from the noninteger number of days it takes 2000 CE, while, in dendrochronology, some labora- Earth to complete an orbit of the Sun. In revising their tories develop multimillennial-long tree-ring chronol- 360-d calendar by adding 5 d, the ancient Egyptians ogies with year zero but others do not. Further were able to slow, but not halt, the divergence of confusion emerges from phasing of the extratropical civil and seasonal calendars (1). -

Library Classification Systems and Organization of Islamic Knowledge Current Global Scenario and Optimal Solution

LRTS 56(3) 171 Library Classification Systems and Organization of Islamic Knowledge Current Global Scenario and Optimal Solution Haroon Idrees Standard library classification systems like Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC), U.S. Library of Congress Classification (LCC), and Universal Decimal Classification (UDC) are internationally known and widely used by librar- ies as the tools for organizing information. Charles Ammi Cutter’s Expansive Classification (EC), James Duff Brown’s Subject Classification (SC), Henry E. Bliss’ Bibliographic Classification (BC), and S. R. Ranganathan’s Colon Classification (CC) also are standard classification systems, but they are less commonly used compared to aforementioned three systems. All these systems are easy to use and convenient for most general collection libraries. However, these systems are not adequate for some special collections. Libraries with rich collec- tions on Islam also face problems while using these systems, although such librar- ies often use expansions in the original systems for their collections. This paper examines this problem and presents a potential optimal solution. The author collected data, using a semistructured interview technique, from a representative sample of thirty libraries in eight countries with strong collections in Islam. These data were analyzed employing qualitative methods. ewey Decimal Classification (DDC), Charles Ammi Cutter’s Expansive Haroon Idrees (h.haroonidrees@gmail .com) is Senior Librarian, Islamic Research D Classification (EC), James Duff Brown’s Subject Classification (SC), U.S. Institute, International Islamic University, Library of Congress Classification (LCC), Universal Decimal Classification Islamabad, Pakistan, and a PhD candi- (UDC), Henry E. Bliss’s Bibliographic Classification (BC), and S. R. Rangana- date at the Berlin School of Library and Information Science, Humboldt Universi- than’s Colon Classification (CC) are internationally known standard classification ty of Berlin. -

Gauss' Calendar Formula for the Day of the Week

GAUSS’ CALENDAR FORMULA FOR THE DAY OF THE WEEK BERNDT E. SCHWERDTFEGER In memory of my father Martin Walter (1910–1977) ABSTRACT. This paper describes a formula of C. F. GAUSS for calculating the day of the week from the calendar date and gives a conceptual proof. A formula for the Julian day number is derived. My implementation of the formula in REXX and C is included. PREFACE GAUSS’ formula calculates the day of the week, Monday, . , Sunday, from the calendar date year-month-day. I learned about it in 1962 when reading the Mathematical Recreations [2] by MAURICE KRAITCHIK (1882–1957). It is stated there without proof, together with an application to a perpetual calendar. This article explains the formula and its mathematical background, including a proof and the concepts behind the algorithms implemented in the program gauss.c. GAUSS never published his formula; it appeared only in 1927 in his Werke [1, [XI, 1.]. For the convenience of the reader I have included this notice in appendix A.1 Berlin, 11 May 2009 © 2001–2018 Berndt E. Schwerdtfeger v1.4a, 14 November 2018 1. GAUSS’ FORMULAEXPLAINED 1.1. The Gauss formula. Given are d day, m month, y year. We split the year into Æ Æ Æ the century part and the two digit year inside the century. For m 3 it is done for the ¸ year y 100 c g, i.e. c [y/100], g y 100 c, such that 0 g 99. For m 1,2 it is Æ ¢ Å Æ Æ ¡ ¢ · · Æ done for the year y 1 100 c g. -

Calendars from Around the World

Calendars from around the world Written by Alan Longstaff © National Maritime Museum 2005 - Contents - Introduction The astronomical basis of calendars Day Months Years Types of calendar Solar Lunar Luni-solar Sidereal Calendars in history Egypt Megalith culture Mesopotamia Ancient China Republican Rome Julian calendar Medieval Christian calendar Gregorian calendar Calendars today Gregorian Hebrew Islamic Indian Chinese Appendices Appendix 1 - Mean solar day Appendix 2 - Why the sidereal year is not the same length as the tropical year Appendix 3 - Factors affecting the visibility of the new crescent Moon Appendix 4 - Standstills Appendix 5 - Mean solar year - Introduction - All human societies have developed ways to determine the length of the year, when the year should begin, and how to divide the year into manageable units of time, such as months, weeks and days. Many systems for doing this – calendars – have been adopted throughout history. About 40 remain in use today. We cannot know when our ancestors first noted the cyclical events in the heavens that govern our sense of passing time. We have proof that Palaeolithic people thought about and recorded the astronomical cycles that give us our modern calendars. For example, a 30,000 year-old animal bone with gouged symbols resembling the phases of the Moon was discovered in France. It is difficult for many of us to imagine how much more important the cycles of the days, months and seasons must have been for people in the past than today. Most of us never experience the true darkness of night, notice the phases of the Moon or feel the full impact of the seasons.