Effects of Nonprofit Competition on Charitable Donations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 5450 FILING 990S - Basics March, 2021

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 5450 FILING 990s - Basics March, 2021 Every Rotary Club 501(c)(4) and every Rotary Foundation 501(c)(3) is required to file a tax return and mail to the IRS every year. A nonprofit, tax-exempt organization does not exempt an organization from the requirement to file. What form to file (depends on gross income and assets of your club): Gross income/Total assets File Form Gross income $50,000 or less 990- N (e- postcard) Gross income >$50,000 <$200,000 990 EZ Gross income > $200,000 or $500,000 total assets 990 WHEN: Due date of return: 15th day of the 5th month after year end November 15th for club and foundation with a June 30th fiscal year end. WHERE: If paper filing: Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Center Ogden, UT 84201-0027 EXTENSION: Available automatic six month extension, use Form 8868 WHEN: File on or before the date the original return is due. WHERE: If paper filing: Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Center Ogden, UT 84201-0045 PENALTIES FOR NONFILING: A penalty of $20 a day (IRC Section 6652(c)(1)(A)) can be charged if a return is filed late. Exceptions and limitations apply. LOSS OF TAX EXEMPT STATUS: If an organization does not file an annual return for 3 consecutive years, its tax exempt status is automatically revoked. The organization which has lost tax-exempt status may need to file tax returns as taxable entity and pay taxes. Has your club lost its tax exempt status? Go to: www.irs.gov Then to: Tax Exempt Organization Search (formerly Select Check) to check club status. -

Download Running Start's 990S

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax 2017 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) G Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Open to Public Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service G Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2017 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2017, and ending , B Check if applicable: C D Employer identification number Address change Running Start 20-8666097 Name change 1310 L Street, NW #820 E Telephone number Initial return Washington, 20005, 2022233895 Final return/terminated Amended return G Gross receipts $ 1,084,331. Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: Susannah Wellford H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes X No H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No Same As C Above If 'No,' attach a list. (see instructions) I Tax-exempt status X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ()H (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 J Website: G runningstart.org H(c) Group exemption number G K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association OtherG L Year of formation: 2007 M State of legal domicile: Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities:Training young women to run for political office on a nonpartisan basis. 2 Check this box G if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

X"997 13 0 a 14 Occupancy, Rent, Utilities, and Maintenance

Short Form OMB No 1545-1150 Fwm 990-EZ, Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 41115- 0 0 form as it may ► Do not enter social seaaity numbers on this be made public. Information about Form 990-EZ and its instructions is at www.bs.gov/lonn9®0. ► ia A For the 2015 calendar year, or tax year beginning October 1 , 2015, and ending September 30 .20 16 g check it appp e C Name of organization D Employer Identification number 0 Address diang• Optimist tntemationa135 Dakotas Manitoba Minnesota District 41-6053928 q Name change Number and street (or P.O. box, if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/surte E Telephone number inmainiturn q F ^ 475 Marley Avenue 204 453-7524 wm q Gly w town, state w province, country, and ZIP w foreign postal code F Group Exemption Amended Appsaeanperilina lonnima. L QY8 Number ► 1334 q Other (specify) G Accounting Method: 0 Cash Accrual ► H Check ► 0 if the organization is not Website: ► www.optitnist-dmm.org required to attach Schedule B J Tax-en pt slates (check only one) - q 501 (c)(3 ) q 501 c 4 t insert no.) q 4947(a)(1 ) or [1527 (Form 990, 990-E. or 990-PF). K Form of organization: q Corporation q Trust 2 Association q Other L Add lines 5b, 6c, and 7b to line 9 to determine gross receipts. If gross receipts are $200,000 or more, or if total assets (Part 11, column (B) below) are $500,000 or more, file Form 990 instead of Form 990-EZ . -

3.2 Precipitation Or Dry-Wet Reconstructions

Climate change in China during the past 2000 years: An overview Ge Quansheng , Zheng Jingyun Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Email: [email protected] Outline 1 Introduction 2 Historical Documents as Proxy 3 Reconstructions and Analyses 4 Summary and Prospects 1. Introduction: E Asia2K Climate System Socio-economic System •typical East Asian •dense population and rapid monsoon climate economic development • significant seasonal and • be susceptible to global inter-annual and inter- warming and extreme decadal variability climate events Climate change study in the past 2ka in East Asian is both beneficial and advantageous. • various types of natural proxy • Plenty of historical documents Fig. Active regional working groups under as proxy the past 2ka theme (PAGES 2009) 2. Historical Documents as Proxy Type Period Amount Chinese classical 1,531 kinds, 137 BC~1470 AD documents 32,251 volumes More than 8,000 1471~1911 (The Ming Local gazettes books (部), 110, and Qing Dynasty) 000 volumes Memos to the About 120,000 1736~1911 emperor pieces Archives of the 1912~1949 20,000 volumes Republic of China More than 200 Private diaries 1550~ books (部) Chinese classical documents AD 833, North China plain: Extreme drought event was occurred, crops were shriveling, no yields, people were in hungry…. Fig. Example for Ancient Chinese writings Local gazettes The 28th year of the Daoguang reign (1848 AD), the 6th (lunar) month, strong wind and heavy rain, the Yangtze River overflowed; the 7th month, strong wind Fig. Gazettes of Yangzhou Prefecture and thunder storm, field published in 1874 AD and houses submerged. -

Tourism, the Economy, Population Growth, and Conservation in Galapagos

Tourism, the Economy, Population Growth, and Conservation in Galapagos Bruce Epler CHARLES DARWIN FOUNDATION Puerto Ayora, Santa Cruz Island, Galapagos Islands, Ecuador Revised and Updated in September 2007 Tourism, the Economy, Population Growth, and Conservation in Galapagos ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is particularly indebted to Susana Cardenas who, in addition to providing general guidance and logistical support, oversaw the distribution and collection of surveys and data entry. Johanna Castañeda assisted in distributing surveys to tourists waiting to depart the airport on Baltra and data entry. Liz Llerena assisted in data entry and interviews with hotel owners on Santa Cruz. Jairo Alvarado circulated surveys in the airport on San Cristóbal. Paulina Buenaño, Carmen Nicolade, and Delsy Jaramillo assisted with surveys and interviews with hotels on Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, and Isabela. Graham Watkins, Executive Director of the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), oversaw the study, provided numerous and relevant data files and studies, and submitted comments that improved the study. Johannah Barry, President of the Galapagos Conservancy, contributed data and insight into tourists’ and industry donations. Roslyn Cameron shared her knowledge about tour vessels, tourists, and fundraising. Craig MacFarland added information on the early years of the CDF, the development of the tourism industry, and ongoing and evolving issues and concerns. Oscar Aguirre, of the Galapagos Chamber of Tourism (CAPTURGAL), generously supplied summaries of survey information collected over several years. Edwin Naula, Head of the Galapagos National Park Service’s Tourism Unit, and Daniel Silva provided useful data compiled by the Park Service. Eliecer Cruz, of the World Wildlife Fund, provided insight into immigration, industry trends, and changes occurring in populated areas. -

The Teen Project & Freehab 990S

The Teen Project & Freehab 990s Please see the following 990 forms for both The Teen Project Inc. and Freehab Inc. herein. Freehab was dissolved and the assets merged under The Teen Project Inc. (the surviving organization) due to the long history, similar mission and supportive recurring donor base as is described herein. The Teen Project has five components: PAD Venice Drop in Center College Housing FREEHAB Life Transformation Center National Shelter Cell Service National Shelter Database OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax 2013 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) G Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Open to Public Department of the Treasury G Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990 and its instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990. Inspection A For the 2013 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2013, and ending , B Check if applicable: C D Employer Identification Number Address change FREEHAB INC 46-1498077 E Name change 22431 B160 ANTONIO PKY #527 Telephone number X Initial return RANCHO SANTA MARGARITA, CA 92688 Terminated Amended return G Gross receipts $ 1,448,938. Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes X No H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No If 'No,' attach a list. (see instructions) I Tax-exempt status X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ()H (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 G J Website: G N/A H(c) Group exemption number T G K Form of organization: X Corporation rust Association Other L Year of formation: 2013 M State of legal domicile: CA Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: ORGANIZATION THAT PROVIDES "STREET TO EMPLOYMENT" SERVICES FOR THE HOMELESS, THE DISPOSED AND SOCIALLY IGNORED. -

CRS-990S-2014-2019.Pdf

CARLOS ROSARIO INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC Form 990 (2018) CHARTER SCHOOL, INC. 52-2157082 Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission: THE CARLOS ROSARIO SCHOOL DELIVERS HIGH QUALITY EDUCATION, CAREER TRAINING, AND SUPPORTIVE SERVICES THAT ENABLE ADULT IMMIGRANTS TO REALIZE THEIR DREAMS WHILE STRENGTHENING OUR COMMUNITY AND ECONOMY. 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Yes X No If "Yes," describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? ~~~~~~ Yes X No If "Yes," describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization's program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 26,606,469. including grants of $ 115,416. ) (Revenue $ 28,605,322. ) MORE THAN FORTY YEARS OF HISTORY SERVING WASHINGTON, D.C.'S DIVERSE IMMIGRANT POPULATION, NATIONALLY AND INTERNATIONALLY RECOGNIZED AS A MODEL IN ADULT EDUCATION. THE SCHOOL OFFERS AN AWARD-WINNING HOLISTIC MODEL OF ADULT EDUCATION FOR IMMIGRANTS INCLUDING CLASSES IN LANGUAGE, LITERACY, GED, CITIZENSHIP AND WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT AS WELL AS COMPREHENSIVE SUPPORTIVE SERVICES. THE SCHOOL SERVES MORE THAN 2,500 STUDENTS AND IS RANKED AS A TIER 1, HIGH PERFORMING SCHOOL BY THE D.C. -

MF2474 Economics of On-Farm Storage

The Economics of On-Farm Storage Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service The interest in grain storage in Kansas and those years. Total production of these four crops other states has escalated recently. This interest exceeded storage capacity in the late 990s, which can be attributed to increased yields due to put pressure on the state’s ability to store grain improved technology and genetics, wide basis and led to the increase in storage capacity in 2000. levels at harvest, and a shift to more corn acres However, since 2000, production levels have been due to the growing number of ethanol plants below the peak levels of the late 990s and the being constructed. More specifically, corn gener- storage pressure that existed at that time generally ally has higher yields than other competing grain has not prevailed in the state, at least on average crops, requiring more storage room, or otherwise – though on a regional basis there have been some replaces crops not dependent on conventional instances of storage pressures. storage, for example, cotton or alfalfa. The rising Since 987 total storage capacity in Kansas demand for storage has led to grain being stored has been above a billion bushels (on-farm grain in temporary structures, the leasing of old facili- storage data first became available in 986). ties, and a renewed interest in the construction of From 987 through 2006 total production of the new storage structures. four major grain crops ranged from 67 to ,253 Kansas traditionally has stored the majority of million bushels, with total production surpassing its grain production in commercial elevators, as a billion bushels eight times. -

School District Reference Map (2010 Census)

42.938990N 42.940561N 114.638441W SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP (2010 CENSUS): Jerome County, ID 113.912115W Shoshone LEGEND 26 73900 SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE Federal American Indian Reservation L'ANSE RES 1880 Dietrich 21790 Off-Reservation Trust Land T1880 State American Indian Reservation Tama Res 4125 Alaska Native Regional Corporation NANA ANRC 52120 24 UNI State (or statistically NEW YORK 36 01260 equivalent entity) County (or statistically ERIE 029 UNI equivalent entity) LINCOLN 063 00900 GOODING 047 Minor Civil Division (MCD)1,2 Bristol town 07485 Consolidated City MILFORD 47500 Incorporated Place 1,3 Davis 18100 Census Designated Place Incline Village 35100 (CDP) 3 E 900 N Unified School District UNI 03370 h t r d o SEC N R Secondary School District 99965 Elementary School District ELM E 7 02220 50 N W 700 N E 700 N DESCRIPTION SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL N 2 Pleasant Lake 0 N 250 E Interstate 3 Water Body 0 W N 400 E U.S. Highway 2 Okefenokee Swamp W 600 N E 600 N Swamp or Marsh R LINCOLN 063 4 C State Highway n l Bering Glacier E Glacier JEROME 053 Marsh Ln 0 0 Other Road 4 N N 350 E 4WD Trail, Stairway, W 500 N Military E 500 N Alley, Walkway, or Ferry Fort Belvoir Southern RR N 800 E Raiload National or State Park, W 450 N Yosemite NP Forest, or Recreation Area Pipeline or 93 Power Line N 200 E W 400 N North Rd E 400 N Inset Area N 300 E A 400 N UNI Ridge or Fence N 450 W N 100 W E 350 N 02940 Property Line Outside Subject Area 900 E N N 900 E UNI E 3 30 03360 Nonvisible Boundary N 200 W W 300 N E 300 N Sugar Loaf Rd or Feature Not 300 N Elsewhere Classified E 290 N N 400 W N 400 E Hall Rd N 300 W W 0 6 1 N 250 W N 525 E E Where state, county, and/or MCD boundaries coincide, the map shows the 22 N 800 E Hall Rd 5 W 200 N N E 200 N N 600 E boundary symbol for only the highest-ranking of these boundaries. -

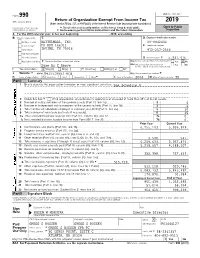

2019 IRS Form

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax (Rev. January 2020) 2019 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) Open to Public Department of the Treasury G Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service G Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2019 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2019, and ending , B Check if applicable: C D Employer identification number Address change BAITULMAAL, INC. 20-0942434 Name change PO BOX 166911 E Telephone number Initial return IRVING, TX 75016 972-257-2564 Final return/terminated Amended return G Gross receipts $ 5,937,476. Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes X No H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No Same As C Above If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( )H (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 J Website: G www.baitulmaal.org H(c) Group exemption number G K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association OtherG L Year of formation: 2004 M State of legal domicile: TX Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: See Schedule O 2 Check this box G if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. 3 Number of voting members of the governing body (Part VI, line 1a) . -

The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000: Augustinian Historiography, Medieval and Modern Author(S): Richard Landes Reviewed Work(S): Source: Speculum, Vol

Medieval Academy of America The Fear of an Apocalyptic Year 1000: Augustinian Historiography, Medieval and Modern Author(s): Richard Landes Reviewed work(s): Source: Speculum, Vol. 75, No. 1 (Jan., 2000), pp. 97-145 Published by: Medieval Academy of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2887426 . Accessed: 04/11/2011 16:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Medieval Academy of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Speculum. http://www.jstor.org The Fear of an ApocalypticYear 1000: Augustinian Historiography, Medieval and Modern By Richard Landes In 1901 George Lincoln Burr published an article in the American Historical Review in which he summarized for American historians a new consensus among their European colleagues: the arrival of the year 1000 had not provoked any apocalyptic expectations.1 This position completely reversed the previous view championed in the mid-nineteenth century by historians like Jules Michelet, who had drawn a dramatic picture of mass apocalyptic expectations climaxing in the year 1000. Despite extensive advances in scholarship since 1900, medieval his- torians continue to accept and repeat this revisionist position, a position that is methodologically jejune and that almost completely ignores the social dynamics of millennial beliefs. -

The Millennium Is Here Again: Is It Panic Time? Jon Paulien

Andrews Univers~rySenlanary Studies, Autumn 1999, Vul. 37, No. 2,167-178 Copyright " 1999 by Andrews University Press. THE MILLENNIUM IS HERE AGAIN: IS IT PANIC TIME? JON PAULIEN Andrews University As the third millennium of the Christian era approaches, it is natural to look back to the previous turn of amillennium for clues regarding what is just ahead. Those who ignore the lessons of history tend to repeat the mistakes of the past. Thus the events surrounding the year 1000 are of more than academic interest. They have the potential to serve as a premonition of events to come. Questions must be answered: Was there a great deal of excitement in Europe as the year 1000 approached? Or is this agitation something we project back to that time because of our own expectations for the year 2000? The purpose of this article is to survey the basic trends in historical study of the year 1000, noting the current state of the evidence and its major interpretations. The article concludes with a brief reflection on the implications of that evidence for our entrance into a new millennium. The Popular View of the Year 1000 The popular view of rnillennial panic around the year 999 seems to have had its origin in isolated passages found in documents published from the end of the sixteenth century through the early part of the nineteenth century.' Prompted by the work of ppular historian Jules Michelet in 1835, encyclopedias, dictionaries, literary annals, comic operas, and novels of the time generally agreed on an account summarized in the following paragraph.2 In the year 999 the people of Europe gathered in panic to await the catastrophic conclusion of all things.