Artistic Research in Music and the Performing Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Syllabus Live-Performance Disc Jockey Techniques 3 Credits

Course Syllabus Live-Performance Disc Jockey Techniques 3 Credits MUC135, Section 33575 Scottsdale Community College, Department of Music Fall 2015 (September 1 to December 18, 2015) Tuesday Evenings 6:30 PM - 9:10 PM (Room MB-136) Instructor: Rob Wegner, B.S., M.A. ([email protected] or [email protected]); Cell: 480-695-6270 Office Hours: Monday’s 6:00 - 7:30PM (Room MB-139) Recommended Text: How to DJ Right: The Art and Science of Playing Records by Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton (Grove Press, 2003). ISBN: 0-8021- 3995-7 Groove Music: The Art and Culture of the Hip-Hop DJ by Mark Katz (Oxford University Press, 2012). ISBN-10: 0195331125 Recommended DVD: Scratch: A Film by Doug Prey by Doug Prey (Palm Pictures, 2001). Required Gear: Headphones (for labs) Additional Suggested Reading: Off the Record by Doug Shannon (1982), Pacesetter Publishing House. Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, The History of the Disc Jockey by Bill Brewster & Frank Broughton (2000), Grove Press. On The Record: The Scratch DJ Academy Guide by Phil White & Luke Crisell (2009), St. Martin’s Griffin. Looking for the Perfect Beat by Kurt B. Reighley (2000), Pocket Books. How to Be a DJ by Chuck Fresh (2001), Brevard Marketing. DJ Culture by Ulf Poschardt (1995), Quartet Books Limited. The Mobile DJ Handbook, 2nd Edition by Stacy Zemon (2003), Focal Press. Turntable Basics by Stephen Webber (2000), Berklee Press. Course Objectives Upon successful completion of this course, you should be able to: explain the historical innovations that led to the evolution of -

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Works for Ensemble English

composed 137 works for ensemble (2 players or more) from 1950 to 2007. SCORES , compact discs, books , posters, videos, music boxes may be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag . A complete list of Stockhausen ’s works and CDs is available free of charge from the Stockhausen-Verlag , Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax: +49 [0 ] 2268-1813; e-mail [email protected]) www.stockhausen.org Karlheinz Stockhausen Works for ensemble (2 players or more) (Among these works for more than 18 players which are usu al ly not per formed by orches tras, but rath er by cham ber ensem bles such as the Lon don Sin fo niet ta , the Ensem ble Inter con tem po rain , the Asko Ensem ble , or Ensem ble Mod ern .) All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are pub lished by Uni ver sal Edi tion in Vien na, with the excep tion of ETUDE, Elec tron ic STUD IES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE , KON TAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYM NEN , which are pub lished since 1993 by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Start ing with work num ber 30, all com po si tions are pub lished by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , Ket ten berg 15, 51515 Kürten, Ger ma ny, and may be ordered di rect ly. [9 ’21”] = dura tion of 9 min utes and 21 sec onds (dura tions with min utes and sec onds: CD dura tions of the Com plete Edi tion ). -

A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a Study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and His Effect on the Trumpet

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet Michael Joseph Berthelot Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Berthelot, Michael Joseph, "A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3187. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SYMPHONIC POEM ON DANTE’S INFERNO AND A STUDY ON KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN AND HIS EFFECT ON THE TRUMPET A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Michael J Berthelot B.M., Louisiana State University, 2000 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 December 2008 Jackie ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dinos Constantinides most of all, because it was his constant support that made this dissertation possible. His patience in guiding me through this entire process was remarkable. It was Dr. Constantinides that taught great things to me about composition, music, and life. -

The Computational Attitude in Music Theory

The Computational Attitude in Music Theory Eamonn Bell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Eamonn Bell All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Computational Attitude in Music Theory Eamonn Bell Music studies’s turn to computation during the twentieth century has engendered particular habits of thought about music, habits that remain in operation long after the music scholar has stepped away from the computer. The computational attitude is a way of thinking about music that is learned at the computer but can be applied away from it. It may be manifest in actual computer use, or in invocations of computationalism, a theory of mind whose influence on twentieth-century music theory is palpable. It may also be manifest in more informal discussions about music, which make liberal use of computational metaphors. In Chapter 1, I describe this attitude, the stakes for considering the computer as one of its instruments, and the kinds of historical sources and methodologies we might draw on to chart its ascendance. The remainder of this dissertation considers distinct and varied cases from the mid-twentieth century in which computers or computationalist musical ideas were used to pursue new musical objects, to quantify and classify musical scores as data, and to instantiate a generally music-structuralist mode of analysis. I present an account of the decades-long effort to prepare an exhaustive and accurate catalog of the all-interval twelve-tone series (Chapter 2). This problem was first posed in the 1920s but was not solved until 1959, when the composer Hanns Jelinek collaborated with the computer engineer Heinz Zemanek to jointly develop and run a computer program. -

TEXTE Zur MUSIK Band 4 Werk-Einführungen Elektronische Musik Weltmusik Vorschläge Und Standpunkte Zum Werk Anderer

Inhalt TEXTE zur MUSIK Band 4 Werk-Einführungen Elektronische Musik Weltmusik Vorschläge und Standpunkte Zum Werk Anderer „Glauben Sie, daβ eine Gesellschaft ohne Wertvorstellungen leben kann?” „Was steht in TEXTE Band 4?” I Werk-Einführungen CHÖRE FÜR DORIS und CHORAl DREI LIEDER SONATINE KREUZSPIEL FORMEL SPIEL SCHLAGTRIO MOMENTE MIXTUR STOP HYMNEN mit Orchester Zur Uraufführung der Orchesterfassung Eine ‚amerikanische’ Aufführung im Freien PROZESSION AUS DEN SIEBEN TAGEN RICHTIGE DAUERN UNBEGRENZT VERBINDUNG TREFFPUNKT NACHTMUSIK ABWÄRTS OBEN UND UNTEN INTENSITÄT SETZ DIE SEGEL ZUR SONNE KOMMUNION ES Fragen und Antworten zur Intuitiven Musik GOLDSTAUB POLE und EXPO MANTRA FÜR KOMMENDE ZEITEN STERNKLANG 1 TRANS ALPHABET Am Himmel wandre ich... YLEM INORI Neues in INORI Vortrag über Hu Atmen gibt das Leben HERBSTMUSIK MUSIK IM BAUCH TIERKREIS Version für Kammerorchester HARLEKIN DER KLEINE HARLEKIN SIRIUS AMOUR JUBILÄUM IN FREUNDSCHAFT DER JAHRESLAUF II Elektronische Musik Vier Kriterien der Elektronischen Musik Fragen und Antworten zu den Vier Kriterien… Die Zukunft der elektroakustischen Apparaturen in der Musik III Weltmusik Erinnerungen an Japan Moderne Japanische Musik und Tradition Weltmusik IV Vorschläge und Standpunkte Interview I: Gespräch mit holländischem Kunstkreis Interview II: Zur Situation (Darmstädter Ferienkurse ΄74) Interview III: Denn alles ist Musik... Interview IV Die Musik und das Kind Du bist, was Du singst – Du wirst, was Du hörst – Vorschläge für die Zukunft des Orchesters Ein Briefwechsel ‚im Geiste der Zeit’ 2 Brief an den Deutschen Musikrat Briefwechsel über das Urheberrecht Silvester-Umfrage Fragen, die keine sind Finden Sie die Programmierung gut ? (Beethoven – Webern – Stockhausen) V Zum Werk Anderer Mahlers Biographie Niemand kann über seinen Schatten springen? Eine Buchbesprechung Über John Cage Zu Schönbergs 100. -

Karlheinz Stockhausen List of Works

Karlheinz Stockhausen List of Works All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are published by Universal Edition in Vienna, with the exception of ETUDE, Electronic STUDIES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE, KONTAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYMNEN, which are published since 1993 by the Stockhausen-Verlag, and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Starting with work number 30, all compositions are published by the Stockhausen-Verlag, Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany, and may be ordered directly. 1 = numeration of the individually performable works. r1 = orchestra works with at least 19 players (or fewer when the instrumentation is unconventional), and works for orchestra with choir. o1 = chamber music works. Among these are several which have more than 18 players, but are usually not performed by orchestras, but rather by chamber ensembles such as the London Sinfonietta, the Ensemble Intercontemporain, the Asko Ensemble, or Ensemble Modern. J35 = Works, which may also be performed as “chamber music” (for example INORI with 2 dancer- mimes and tape [instead of orchestra] or works for choir in which the choir may be played back on tape. 1. ex 47 = 1st derivative of Work No. 47. [9’21”] = duration of 9 minutes and 21 seconds (durations with minutes and seconds: CD durations of the Complete Edition). U. E. = Universal Edition. St. = Stockhausen-Verlag. For most of the works, an electro-acoustic installation is indicated. Detailed information about the required equipment may be found in the scores. In very small halls (for less than 100 people), it is possible to omit amplification for some solo works and works for small ensembles. -

Kreuzspiel, Louange À L'éternité De Jésus, and Mashups Three

Kreuzspiel, Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus, and Mashups Three Analytical Essays on Music from the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Thomas Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2013 Committee: Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ©Copyright 2013 Thomas Johnson Johnson, Kreuzspiel, Louange, and Mashups TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1: Stockhausen’s Kreuzspiel and its Connection to his Oeuvre ….….….….….…........1 Chapter 2: Harmonic Development and The Theme of Eternity In Messiaen’s Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus …………………………………….....37 Chapter 3: Meaning and Structure in Mashups ………………………………………………….60 Appendix I: Mashups and Constituent Songs from the Text with Links ……………………....103 Appendix II: List of Ways Charles Ives Used Existing Musical Material ….….….….……...104 Appendix III: DJ Overdub’s “Five Step” with Constituent Samples ……………………….....105 Bibliography …………………………………........……...…………….…………………….106 i Johnson, Kreuzspiel, Louange, and Mashups LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE 1.1. Phase 1 pitched instruments ……………………………………………....………5 EXAMPLE 1.2. Phase 1 tom-toms …………………………………………………………………5 EXAMPLE 1.3. Registral rotation with linked pitches in measures 14-91 ………………………...6 EXAMPLE 1.4. Tumbas part from measures 7-9, with duration values above …………………....7 EXAMPLE 1.5. Phase 1 tumba series, measures 7-85 ……………………………………………..7 EXAMPLE 1.6. The serial treatment of the tom-toms in Phase 1 …………………………........…9 EXAMPLE 1.7. Phase two pitched mode ………………………………………………....……...11 EXAMPLE 1.8. Phase two percussion mode ………………………………………………....…..11 EXAMPLE 1.9. Pitched instruments section II …………………………………………………...13 EXAMPLE 1.10. Segmental grouping in pitched instruments in section II ………………….......14 EXAMPLE 1.11. -

House-Constructor

1,3 GB Plug-ins & MIDI auf der Heft-DVD Beat Producer-Tricks: House-Constructor House ist eine der ältesten Konstanten elektronischer Musik und existiert mittlerweile in zahlreichen Facetten, von Progres- sive- über Deep- bis hin zum modernen Tech-House. Was prägt den Sound des Originals und wie wird er produziert? In dieser Folge der Constructor-Serie bauen Sie einen kompletten House-Track von der Pike auf. von Marco Scherer Anspiel-Tipps: ie Wurzeln von House reichen nach wie vor aktiv, aber auch Nachfolger wie chen Varianten vor. Teils in Form von Adlibs, zurück bis zu den Anfängen des Armand van Helden, Basement Jaxx, Eric einzelnen Worten oder – wie auch gern in DTechno, mancherorts werden sie Pryzd oder Afrojack tragen das Erbe erfolg- Minimal und Glitch verwendet – kurzen sogar als der Ursprung selbst genannt. Alles reich weiter. Phrasen, die nacheinander abgefeuert wer- beginnt mit dem „Warehouse“, einem Club den. Ebenso zeichnen sich viele House-Tracks in Chicago: Frankie Knuckles experimentiert Was ist House? durch Gesang mit Strophen und Refrains mit den „Extended Versions“ seiner Disco- House-Tracks zeichnen sich vor allem durch aus, wie man es von Pop-Songs her kennt. Vinyls, die sich durch lange und auf den Beat zwei Dinge aus: Vier-Viertel-Rhythmus und reduzierte Passagen auszeichnen. Sein Publi- Vocals. Die Beats folgen sehr einfachen und Die Werkzeuge kum dankt es ihm mit frenetischen Tanzein- eingängigen Mustern, die schon nach weni- Aktuelle House Produktionen lassen sich in lagen und weitere DJs springen auf den los- gen Sekunden klar erfasst sind. Die Sounds jeder DAW realisieren, je nach Genre auch Mr. -

Ιnspired by the Purification Rituals Held by the Minoans During the Bronze

Ιnspired by the purification rituals held by the Minoans during the Bronze Age MAGIC MONDAYS at The Beach House The ultimate amalgam of extraordinary experiences packed into one evening – we proudly present Magic Mondays. Starting with a contemporary interpretation of the spiritual ceremony, created and practiced by the Minoans during the Bronze Age. The purifying blessing with laurel and sage calls on the divine goddess of the sun to relinquish her power and give way to the night. The evening unfolds whilst our renowned artists and DJs reveal their talent on The Beach House decks. Join us and be a part of the communal feeling that is Magic Mondays at The Beach House. VISITING ARTISTS BEN BRIDGEWATER MAY 27 / JUN 10 / SEP 2 Ben has been a permanent fixture on the London party scene for 20 years, as well as playing at the world's coolest parties for royals and roughnecks, viscounts and vagabonds. He has held residencies at The Arts Club, The Scotch, The Box, 5 Herford St, The Double Club, The Groucho and The Cuckoo Club, supported Stevie Wonder and The Stones, played at parties in Paris for Stella McCartney as well as at film premieres for James Bond and Star Wars. As co-founder and creative director of Playlister, Daios Cove's in-house music team, Ben understands the sound of The Beach House better than anyone. ALEX NUDE JUN 3 / SEP 9 / OCT 7 Having DJed for over a decade, Alex Nude has been based in Mykonos since 2013. As resident DJ for Scorpios Mykonos for the first three years he became well-known for his branded night 'Blaq Theory' with great tech sounds recorded at the world-class Nightclub Moni, also in Mykonos. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Hubert Howe\My Documents\Courses

Musical works of Karlheinz Stockhausen (b. 1928) [Information taken from www.stockhausen.org.] Nr. Chöre für Doris for choir a capella, 1950 Drei Lieder for chorus and chamber orchestra, 1950 Chorale for four-part choir a capella, 1950 Sonatine for violin and piano, 1951 Kreuzspiel (“Cross-play”) for oboe, bass clarinet, piano, percussion, 1951 Formel (“Formula”) for orchestra, 1951 Etüde, musique concrète, 1952 Spiel (“Play”) for orchestra, 1952 Schlagtrio (percussion trio), for piano and 3x2 timpani, 1952 Punkte (“Points”) for orchestra, 1952 (revised, 1962) 1 Kontra-Punkte (“Counter-points”) for 10 instruments, 1952-3 2 Klavierstücke I-IV (Piano pieces I-IV), 1952-3 (Klavierstück IV revised 1961) 3/I Studie I, electronic music, 1954 3/II Studie II, electronic music, 1954 4 Klavierstücke V-X, (Piano pieces V-X), 1954-5 (Klavierstück X revised 1961) 5 Zeitmasze (“Tempi”) for woodwind quintet, 1955-6 6 Gruppen (“Groups”) for three orchestras, 1955-57 7 Klavierstück XI (Piano piece XI), 1956 8 Gesang der Jünglinge (“Song of the Youths”), electronic music, 1955-6 9 Zyklus (“Cycle”) for one percussionist, 1959 10 Carré for four orchestras and choruses, 1959-60 11 Refrain for three players, 1959 12 Kontakte (“Contacts”) for electronic sounds, 1959-60 Kontakte for electronic sounds, piano and percussion, 1959-60 Originale (“Originals”), musical theater with Kontakte, 1961 13 Momente (“Moments”) for soprano, four choral groups and 13 instruments, 1962-4 (Revised 1965, 1998) 14 Plus/Minus 2 x 7 pages for elaboration, 1963 15 Mikrophonie I (“Microphony -

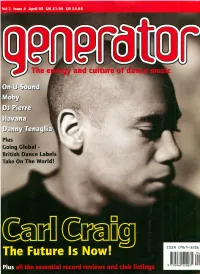

Generator Magazine, 4-8 One) to : Sven Vath Competition, Generator, Project for R&S, Due for Release in the Early Peartree Street, London, Ecl V 3SB

and culture of Plus Going Global - British Dance Labels Take On The World! ISSN 0969-5206 11 111 " 9 770969 ,,,o,, I! I OW HMV • KNOW Contents April 1995 Vol 2 Issue 3 Features 10 Moby 14 Move D 19 Riccardo Rocchi 20 Danny Tenaglia 24 Crew 2000 2 6 Carl Craig 32 DJ Pierre 37 Dimitri 38 A Bad Night Out? 40 Havana 44 On-U-Sound 52 Caroline Lavelle 54 Going Global! 70 DJ Rap 81 Millennium Records Live 65 Secret Knowledge 68 A Positive Life Regulars 5 Letters 8 From The Floor 50 Fashion 57 Album Reviews 61 Single Reviews 71 Listings 82 The World According To ... Generator 3 YOU IOlC good music, ri&11t? Sl\\\.tle, 12 KILLER MASTERCUTS FLOOR-FILLERS ~JIIA1fJ}J11JWJ}{@]1J11~&tjjiiliJ&kiMJj P u6-:M44kiL~ffi:t.t&8/W ~-i~11J#JaJJA/JliliID1il1- ~~11JID11ELJ.JfiZW-J!U11-»R dftlhiMillb~JfJJlkmt@U¾l E-.fiW!JJlJMiijifJ~)JJt).ilw,i1!J!in 11Y$#~1kl!I . ' . rJOJ,t'tJi;M)J4&,j~ letters.·• • Editor Dear Generator, Dear Generator, and wasting hours-worth of Tim Barr Que Pasa? Something seems to My friends and I are wondering conversationa l aimlessness in Assistant Editor (Advertising) have happened at Generator about a frequent visitor to your an attempt to discover exactly Barney York HQ. One minute, there I was letters page. It seems that the where it was you left those last thinking your magazine was military have moved up north three papers, or, indeed, your Art Direction & Design Paul Haggis & Derek Neeps well and t ruly firmed up with and installed someone with head. -

STOCKHAUSEN-VERLAG Price List English

Stockhausen-Verla g Price list 2018 All Stockhausen scores which are published by Universal Edition , Vienna, may also be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag (prices on request) . scores / books / posters / music boxes: Scores Quantity € 3 x REFRAIN 2000 ............................................................ –––– 45.00 AM HIMME L WANDR E ICH . ............................................ –––– 38.00 AMOUR for clarinet ........................................................... –––– 22.00 for flute ............................................................... –––– 22.00 for saxophone . ..................................................... –––– 33.00 ANTRAG ......................................................................... –––– 35.00 ARGUMENT .................................................................... –––– 46.00 ARIES ............................................................................. –––– 24.50 ATMEN GIBT DAS LEBEN .............................................. –––– 50.50 AVE ................................................................................. –––– 76.00 th BALANCE – 7 Hour from KLANG ................................... –––– 60.00 BASSETSU ...................................................................... –––– 40.00 BASSETSU-TRIO ............................................................. –––– 34.00 Betmoment ....................................................................... –––– 60.00 BIJOU .............................................................................. ––––