The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Witness for Freedom: Curriculum Guide for Using Primary Documents

WITNESS FOR FREEDOM A Curriculum Guide for Using Primary Documents to teach Abolitionist History By Wendy Kohler and Gaylord Saulsberry Published by The Five College Public School Partnership 97 Spring Street, Amherst, MA 01002 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Witness for Freedom project began in 1995 with the vision of Christine Compston, then Director of the National History Education Network. She approached Mary Alice Wilson at the Five College Public School Partnership with the idea of developing an institute for social studies teachers that would introduce them to the documents recently published by C. Peter Ripley in Witness for Freedom: African American Voices on Race, Slavery, and Emancipation. Together they solicited the participation of David Blight, Professor of History at Amherst College, and author of Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee. The Witness for Freedom Summer Institute was held in 1996 under their direction and involved twenty teachers from Western Massachusetts. The project was made possible by a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the National Archives with additional support from the Nan and Matilda Heydt Fund of the Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts. The publication of this guide by Wendy Kohler and Gaylord Saulsberry of the Amherst Public Schools offers specific guidance for Massachusetts teachers and district personnel concerned with aligning classroom instruction with the state curriculum frameworks. The Five College Public School Partnership thanks all of the above for their involvement in this project. Additional copies of this guide and the Witness for Freedom Handbook for Professional Development are available from the Five College Public School Partnership, 97 Spring Street, Amherst, MA 01002. -

Dueling, Honor and Sensibility in Eighteenth-Century Spanish Sentimental Comedies

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES Kristie Bulleit Niemeier University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Niemeier, Kristie Bulleit, "DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 12. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/12 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kristie Bulleit Niemeier The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 DUELING, HONOR AND SENSIBILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH SENTIMENTAL COMEDIES _________________________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _________________________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the University of Kentucky By Kristie Bulleit Niemeier Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ana Rueda, Professor of Spanish Literature Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Kristie Bulleit Niemeier 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION DUELING, HONOR AND -

J Ohn S. and J Ames L. K Night F Oundation

A NNUAL REPORT 1999 T HE FIRST FIFTY YEARS J OHN S. AND JAMES L. KNIGHT FOUNDATION he John S. and James L. Kn i ght Fo u n d a ti on was estab- TA B L E O F CO N T E N T S l i s h ed in 1950 as a priva te fo u n d a ti on indepen d en t Tof the Kn i g ht bro t h ers’ n e ws p a per en terpri s e s . It is C h a i r m a n’s Letter 2 ded i c a ted to f urt h ering their ideals of s ervi ce to com mu n i ty, to the highest standards of j o u r n a l i s t ic excell en ce and to the Pr e s i d e n t ’s Message 4 defense of a free pre s s . In both their publishing and ph i l a n t h ropic undert a k i n g s , History 5 the Kn i ght bro t h ers shared a broad vi s i on and uncom m on devo ti on to the com m on wel f a re . It is those ide a l s , as well as Philanthropy Takes Root 6 t h eir ph i l a n t h ropic intere s t s , to wh i ch the Fo u n d a ti on rem a i n s The First Fifty Years 8 f a i t h f u l . -

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

Viewer's Guide

SELMA T H E BRIDGE T O T H E BALLOT TEACHING TOLERANCE A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER VIEWER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-12 Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is the story of a courageous group of Alabama students and teachers who, along with other activists, fought a nonviolent battle to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Standing in their way: a century of Jim Crow, a resistant and segregationist state, and a federal govern- ment slow to fully embrace equality. By organizing and marching bravely in the face of intimidation, violence, arrest and even murder, these change-makers achieved one of the most significant victories of the civil rights era. The 40-minute film is recommended for students in grades 6 to 12. The Viewer’s Guide supports classroom viewing of Selma with background information, discussion questions and lessons. In Do Something!, a culminating activity, students are encouraged to get involved locally to promote voting and voter registration. For more information and updates, visit tolerance.org/selma-bridge-to-ballot. Send feedback and ideas to [email protected]. Contents How to Use This Guide 4 Part One About the Film and the Selma-to-Montgomery March 6 Part Two Preparing to Teach with Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot 16 Part Three Before Viewing 18 Part Four During Viewing 22 Part Five After Viewing 32 Part Six Do Something! 37 Part Seven Additional Resources 41 Part Eight Answer Keys 45 Acknowledgements 57 teaching tolerance tolerance.org How to Use This Guide Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a versatile film that can be used in a variety of courses to spark conversations about civil rights, activism, the proper use of government power and the role of the citizen. -

Mississippi Freedom Summer: Compromising Safety in the Midst of Conflict

Mississippi Freedom Summer: Compromising Safety in the Midst of Conflict Chu-Yin Weng and Joanna Chen Junior Division Group Documentary Process Paper Word Count: 494 This year, we started school by learning about the Civil Rights Movement in our social studies class. We were fascinated by the events that happened during this time of discrimination and segregation, and saddened by the violence and intimidation used by many to oppress African Americans and deny them their Constitutional rights. When we learned about the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964, we were inspired and shocked that there were many people who were willing to compromise their personal safety during this conflict in order to achieve political equality for African Americans in Mississippi. To learn more, we read the book, The Freedom Summer Murders, by Don Mitchell. The story of these volunteers remained with us, and when this year’s theme of “Conflict and Compromise” was introduced, we thought that the topic was a perfect match and a great opportunity for us to learn more. This is also a meaningful topic because of the current state of race relations in America. Though much progress has been made, events over the last few years, including a 2013 Supreme Court decision that could impact voting rights, show the nation still has a way to go toward achieving full racial equality. In addition to reading The Freedom Summer Murders, we used many databases and research tools provided by our school to gather more information. We also used various websites and documentaries, such as PBS American Experience, Library Of Congress, and Eyes on the Prize. -

Freedom Summer

MISSISSIPPI BURNING THE FREEDOM SUMMER OF 1964 Prepared by Glenn Oney For Teaching American History The Situation • According to the Census, 45% of Mississippi's population is Black, but in 1964 less than 5% of Blacks are registered to vote state-wide. • In the rural counties where Blacks are a majority — or even a significant minority — of the population, Black registration is virtually nil. The Situation • For example, in some of the counties where there are Freedom Summer projects (main project town shown in parenthesis): Whites Blacks County (Town) Number Eligible Number Voters Percentage Number Eligible Number Voters Percentage Coahoma (Clarksdale) 5338 4030 73% 14004 1061 8% Holmes (Tchula) 4773 3530 74% 8757 8 - Le Flore (Greenwood) 10274 7168 70% 13567 268 2% Marshall (Holly Spgs) 4342 4162 96% 7168 57 1% Panola (Batesville) 7369 5309 69% 7250 2 - Tallahatchie (Charleston) 5099 4330 85% 6438 5 - Pike (McComb) 12163 7864 65% 6936 150 - Source: 1964 MFDP report derived from court cases and Federal reports. The Situation • To maintain segregation and deny Blacks their citizenship rights — and to continue reaping the economic benefits of racial exploitation — the white power structure has turned Mississippi into a "closed society" ruled by fear from the top down. • Rather than mechanize as other Southern states have done, much of Mississippi agriculture continues to rely on cheap Black labor. • But with the rise of the Freedom Movement, the White Citizens Council is now urging plantation owners to replace Black sharecroppers and farm hands with machines. • This is a deliberate strategy to force Blacks out of the state before they can achieve any share of political power. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

The Complex Relationship Between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement

The Gettysburg Historical Journal Volume 20 Article 8 May 2021 The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement Hannah Labovitz Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Labovitz, Hannah (2021) "The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 20 , Article 8. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol20/iss1/8 This open access article is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement Abstract The Civil Rights Movement occurred throughout a substantial portion of the twentieth century, dedicated to fighting for equal rights for African Americans through various forms of activism. The movement had a profound impact on a number of different communities in the United States and around the world as demonstrated by the continued international attention marked by recent iterations of the Black Lives Matter and ‘Never Again’ movements. One community that had a complex reaction to the movement, played a major role within it, and was impacted by it was the American Jewish community. The African American community and the Jewish community were bonded by a similar exclusion from mainstream American society and a historic empathetic connection that would carry on into the mid-20th century; however, beginning in the late 1960s, the partnership between the groups eventually faced challenges and began to dissolve, only to resurface again in the twenty-first century. -

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963 Compiled and Edited by Stephen Coester '63 Dedicated to the Twenty-Eight Classmates Who Died in the Line of Duty ............ 3 Vietnam Stories ...................................................................................................... 4 SHOT DOWN OVER NORTH VIETNAM by Jon Harris ......................................... 4 THE VOLUNTEER by Ray Heins ......................................................................... 5 Air Raid in the Tonkin Gulf by Ray Heins ......................................................... 16 Lost over Vietnam by Dick Jones ......................................................................... 23 Through the Looking Glass by Dave Moore ........................................................ 27 Service In The Field Artillery by Steve Jacoby ..................................................... 32 A Vietnam story from Peter Quinton .................................................................... 64 Mike Cronin, Exemplary Graduate by Dick Nelson '64 ........................................ 66 SUNK by Ray Heins ............................................................................................. 72 TRIDENTS in the Vietnam War by A. Scott Wilson ............................................. 76 Tale of Cubi Point and Olongapo City by Dick Jones ........................................ 102 Ken Sanger's Rescue by Ken Sanger ................................................................ 106 -

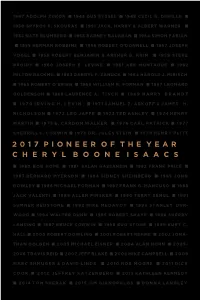

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

National Delta Kappa Alpha

,...., National Delta Kappa Alpha Honorary Cinema Fraternity. 31sT ANNIVERSARY HONORARY AWARDS BANQUET honoring GREER GARSON ROSS HUNTER STEVE MCQUEEN February 9, 1969 TOWN and GOWN University of Southern California PROGRAM I. Opening Dr. Norman Topping, President of USC II. Representing Cinema Dr. Bernard R. Kantor, Chairman, Cinema III. Representing DKA Susan Lang Presentation of Associate Awards IV. Special Introductions Mrs. Norman Taurog V. Master of Ceremonies Jerry Lewis VI. Tribute to Honorary l\llembers of DKA VII. Presentation of Honorary Awards to: Greer Garson, Ross Hunter, Steve McQueen VIII. In closing Dr. Norman Topping Banquet Committee of USC Friends and Alumni Mrs. Tichi Wilkerson Miles, chairman Mr. Stanley Musgrove Mr. Earl Bellamy Mrs. Lewis Rachmil Mrs. Harry Brand Mrs. William Schaefer Mr. George Cukor Mrs. Sheldon Schrager Mrs. Albert Dorskin Mr. Walter Scott Mrs. Beatrice Greenough Mrs. Norman Taurog Mrs. Bernard Kantor Mr. King Vidor Mr. Arthur Knight Mr. Jack L. Warner Mr. Jerry Lewis Mr. Robert Wise Mr. Norman Jewison is unable to be present this evening. He will re ceive his award next year. We are grateful to the assistance of 20th Century Fox, Universal studios, United Artists and Warner Seven Arts. DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA In 1929, the University of Southern California in cooperation with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences offered a course described in the Liberal Arts Catalogue as : Introduction to Photoplay: A general introduction to a study of the motion picture art and industry; its mechanical founda tion and history; the silent photoplay and the photoplay with sound and voice; the scenario; the actor's art; pictorial effects; commercial requirements; principles of criticism; ethical and educational features; lectures; class discussions, assigned read ings and reports.