Asphyxiation of an Endangered Cook Inlet Beluga Whale, Delphinapterus Leucas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Mammals of Hudson Strait the Following Marine Mammals Are Common to Hudson Strait, However, Other Species May Also Be Seen

Marine Mammals of Hudson Strait The following marine mammals are common to Hudson Strait, however, other species may also be seen. It’s possible for marine mammals to venture outside of their common habitats and may be seen elsewhere. Bowhead Whale Length: 13-19 m Appearance: Stocky, with large head. Blue-black body with white markings on the chin, belly and just forward of the tail. No dorsal fin or ridge. Two blow holes, no teeth, has baleen. Behaviour: Blow is V-shaped and bushy, reaching 6 m in height. Often alone but sometimes in groups of 2-10. Habitat: Leads and cracks in pack ice during winter and in open water during summer. Status: Special concern Beluga Whale Length: 4-5 m Appearance: Adults are almost entirely white with a tough dorsal ridge and no dorsal fin. Young are grey. Behaviour: Blow is low and hardly visible. Not much of the body is visible out of the water. Found in small groups, but sometimes hundreds to thousands during annual migrations. Habitat: Found in open water year-round. Prefer shallow coastal water during summer and water near pack ice in winter. Killer Whale Status: Endangered Length: 8-9 m Appearance: Black body with white throat, belly and underside and white spot behind eye. Triangular dorsal fin in the middle of the back. Male dorsal fin can be up to 2 m in high. Behaviour: Blow is tall and column shaped; approximately 4 m in height. Narwhal Typically form groups of 2-25. Length: 4-5 m Habitat: Coastal water and open seas, often in water less than 200 m depth. -

Chlorinated Organic Contaminants in Blubber Biopsies from Northwestern Atlantic Balaenopterid Whales Summering in the Gulf of St Lawrence

Marine Environmental Research, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 201-223, 1997 0 1997 Elsevier Science Ltd All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain PII: SOl41-1136(97)00004-4 0141-1136/97 $17.00+0.00 Chlorinated Organic Contaminants in Blubber Biopsies from Northwestern Atlantic Balaenopterid Whales Summering in the Gulf of St Lawrence J. M. Gauthier,a* C. D. Metcalfe” & R. Sear@ “Environmental and Resources Studies, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada K9J 7B8 bMingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS), 285 Green, St. Lambert, Quebec, Canada J4P IT3 (Received 16 May 1996; revised version received 16 December 1996; accepted 29 December 1996. Published June 1997) ABSTRACT Concentrations and patterns of chlorinated biphenyls (CBS) and other persistent organochlorine compounds (OCs) were determined from small blubber biopsy samples collected from northwestern Atlantic minke (Balaenoptera acuros- trata) , fin (Balaenoptera physalus), blue (Balaenoptera musculus) , and humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) whales summering in the Gurf of St. Lawrence, Quebec. Concentrations of CPCB (sum of 19 congeners) in biopsy samples ranged from 0.2-10 pg g-’ lipid, and congeners 52, 101, 118, 153, 138 and 180 accounted for 79% of CPCB. Mean concentration of the sum of non- ortho CB congeners in selected biopsy samples was 2 ng g-t lipid, and relative concentrations of these analytes were: 77 > 126 > 81> 169. Concentrations of XDDT ranged from 0.613 pg g-t lipid, and the average proportion of DDE to CDDT was 72%. All other organochlorine analytes were present at concentra- tions below 2 pg g-t lipid. On average, cis-nonachlor, trans-nonachlor and oxy- chlordane accounted for 27, 26 and 23%, respectively, of the chlordane-related analytes, and cl-hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) comprised 67% of XHCH. -

Federal Register/Vol. 80, No. 162/Friday, August 21, 2015/Notices

50990 Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 162 / Friday, August 21, 2015 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE An authorization for incidental scan sonar, geophysical resistivity takings shall be granted if NMFS finds meters, and magnetometer to National Oceanic and Atmospheric that the taking will have a negligible characterize the bottom surface and Administration impact on the species or stock(s), will subsurface. The planned shallow RIN 0648–XE018 not have an unmitigable adverse impact geotechnical investigations include on the availability of the species or vibracoring, sediment grab sampling, Takes of Marine Mammals Incidental to stock(s) for subsistence uses (where and piezo-cone penetration testing Specified Activities; Taking Marine relevant), and if the permissible (PCPT) to directly evaluate seabed Mammals Incidental to Geophysical methods of taking and requirements features and soil conditions. and Geotechnical Survey in Cook Inlet, pertaining to the mitigation, monitoring Geotechnical borings are planned at Alaska and reporting of such takings are set potential shoreline crossings and in the forth. NMFS has defined ‘‘negligible terminal boring subarea within the AGENCY: National Marine Fisheries impact’’ in 50 CFR 216.103 as ‘‘an Marine Terminal survey area, and will Service (NMFS), National Oceanic and impact resulting from the specified be used to collect information on the Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), activity that cannot be reasonably mechanical properties of in-situ soils to Commerce. expected to, and is not reasonably likely support feasibility studies for ACTION: Notice; issuance of an incidental to, adversely affect the species or stock construction crossing techniques and harassment authorization. through effects on annual rates of decisions on siting and design of pilings, dolphins, and other marine SUMMARY: NMFS is issuing an recruitment or survival.’’ structures. -

Dall's Porpoise

Dall’s Porpoise Phocoenoides dalli, commonly known as the Dall’s porpoise, is most easily recognized by its unique black and white markings similar to those of a killer whale/orca. It was named by the American naturalist William Healey Dall who was the first to collect a specimen. The Dall’s porpoise is capable of swimming in excess of 30 knots and is often seen riding along side the bows of boats. General description: The Dall’s porpoise is black with white markings. Most commonly the animal will be mostly black with large white sections on the sides, belly, on the edges of the flukes, and around the dorsal fin, though there are exceptions to this pattern. The Dall’s porpoise is born at an approximate size of 3ft. The average size of an adult is 6.4 ft and weighs approximately 300 lbs. The body is stocky and more powerful than other members of phocoenidae (porpoises). The head is small and lacks a distinct beak. The flippers are small, pointed, and located near the head. The dorsal fin is triangular in shape with a hooked tip. The mouth of the Dall’s porpoise is small and has a slight underbite. Food habits: Dall’s porpoises eat a wide variety of prey species. In some areas they eat squid, but in other areas they may feed on small schooling fishes such as capelin, lantern fish (Myctophids), and herring. They generally forage at night. Life history: Female Dall’s porpoises reach sexual maturity at between 3 and 6 years of age and males around 5 to 8 years, though there is little known about their mating habits. -

Review of Small Cetaceans. Distribution, Behaviour, Migration and Threats

Review of Small Cetaceans Distribution, Behaviour, Migration and Threats by Boris M. Culik Illustrations by Maurizio Wurtz, Artescienza Marine Mammal Action Plan / Regional Seas Reports and Studies no. 177 Published by United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Secretariat of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). Review of Small Cetaceans. Distribution, Behaviour, Migration and Threats. 2004. Compiled for CMS by Boris M. Culik. Illustrations by Maurizio Wurtz, Artescienza. UNEP / CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 343 pages. Marine Mammal Action Plan / Regional Seas Reports and Studies no. 177 Produced by CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany in collaboration with UNEP Coordination team Marco Barbieri, Veronika Lenarz, Laura Meszaros, Hanneke Van Lavieren Editing Rüdiger Strempel Design Karina Waedt The author Boris M. Culik is associate Professor The drawings stem from Prof. Maurizio of Marine Zoology at the Leibnitz Institute of Wurtz, Dept. of Biology at Genova Univer- Marine Sciences at Kiel University (IFM-GEOMAR) sity and illustrator/artist at Artescienza. and works free-lance as a marine biologist. Contact address: Contact address: Prof. Dr. Boris Culik Prof. Maurizio Wurtz F3: Forschung / Fakten / Fantasie Dept. of Biology, Genova University Am Reff 1 Viale Benedetto XV, 5 24226 Heikendorf, Germany 16132 Genova, Italy Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.fh3.de www.artescienza.org © 2004 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) / Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. -

Magnetic Resonance Images of the Brain of a Dwarf Sperm Whale (Kogia Simus)

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 7-2003 Magnetic Resonance Images of the Brain of a Dwarf Sperm Whale (Kogia simus) L. Marino Emory University K. Sudheimer Michigan State University D. A. Pabst University of North Carolina - Wilmington J. I. Johnson Michigan State University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_vsm Part of the Animal Structures Commons, Animal Studies Commons, and the Veterinary Anatomy Commons Recommended Citation Marino, L., Sudheimer, K., Pabst, D. A., McLellan, W. A., & Johnson, J. I. (2003). Magnetic resonance images of the brain of a dwarf sperm whale (Kogia simus). Journal of anatomy, 203(1), 57-76. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Magnetic resonance images of the brain of a dwarf sperm whale (Kogia simus) L. Marino1, K. Sudheimer2, D. A. Pabst3, W. A. McLellan3, and J. I. Johnson2 1 Emory University 2 Michigan State University 3 University of North Carolina at Wilmington KEYWORDS Brain, dwarf sperm whale, Kogia, MRI ABSTRACT Cetacean (dolphin, whale and porpoise) brains are among the least studied mammalian brains because of the difficulty of collecting and histologically preparing such relatively rare and large specimens. Among cetaceans, there exist relatively few studies of the brain of the dwarf sperm whale (Kogia simus). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers a means of observing the internal structure of the brain when traditional histological procedures are not practical. Therefore, MRI has become a critical tool in the study of the brain of cetaceans and other large species. -

Beluga Whales and Climate Change

BELUGA WHALES AND CLIMATE CHANGE © Bill Liao Summary are changes in populations of their prey, changes in ice conditions (more ice entrapment is a possibility), greater • Beluga whales live in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters competition with co-predators, more frequent predation and are sociable and vocal animals. They are hunted by by killer whales and exposure to novel pathogens. indigenous Arctic people for food and are captured alive on a relatively small scale in eastern Russia to supply the • As Arctic ice cover rapidly declines and the passages live animal display industry throughout the world. across northern landmasses become more navigable, humans will gain easier access to formerly pristine areas • Climate change is likely to affect Belugas both that have long served as refuges for Belugas and other directly through ecological interactions and indirectly marine mammals. through its effects on human activity. • Belugas are increasingly at risk from vessel and • Among the ecological factors that may affect Belugas industrial noise, ship strikes and toxin exposure. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species ™ BELUGA WHALES AND CLIMATE CHANGE The scientific name for the Beluga Whale (Delphinapterus year. But new evidence suggests that only one dentine leucas) means “white dolphin without wings”. Adult layer is laid down per year, and as a result, estimates of Belugas are entirely white and their common name Beluga longevity have at least doubled to 60 years or comes from the Russian word belukha or “white one”. more, with significant implications for population growth projections. Belugas are toothed whales that measure up to 4 (females) or 5.5 metres (males). -

BOEM ESP Ongoing Studies Template

Environmental Studies Program: Ongoing Study Title Aerial Surveys of Arctic Marine Mammals (ASAMM) – Personnel and Aircraft Needs (AK-16-01) Administered by Alaska Regional Office BOEM Contact(s) Rick Raymond, [email protected] Conducting Organizations(s) NOAA-MML; USDOI National Business Center Total BOEM Cost $11,437,309 plus Joint Funding (~$420,000) Performance Period FY 2016–2020 Final Report Due June 2020 Date Revised January 21, 2021 PICOC Summary Problem Information is needed about distributions and relative densities of bowhead whales and other marine mammals to support NEPA analyses related to oil and gas exploration and development activities in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas. Intervention Aerial surveys are conducted in the Chukchi Sea and Beaufort Sea Planning Areas from mid-July to the end of October to observe the fall migration of the bowhead whales. Comparison Past surveys are available for comparison with new data to assess whether changes in distribution or abundance have occurred since the earlier surveys were completed. Outcome This continuation of long-term monitoring activities provides updated information about distribution and abundance of bowheads and other marine mammals in the U.S. Arctic areas. Context Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea BOEM Information Need(s): This study will maintain long-term monitoring information about potential impacts to marine mammals from OCS oil and gas-related activities and subsequent leasing in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. The information will assist BOEM in NEPA analyses for lease sales, EPs, and DPPs, ESA Section 7 consultations, and decision-making in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas. Background: Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus), gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus), beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas), Pacific walrus (Odobenus rosmarus divergens), polar bears (Ursus maritimus), bearded seals (Phoca fasciata), and several other species of ice seals are known to occupy the Chukchi Sea, at least during some seasons. -

Appendix E Marine Mammal Density Report

Appendix E Marine Mammal Density Report GULF OF ALASKA NAVY TRAINING ACTIVITIES EIS/OEIS FINAL (MARCH 2011) TABLE OF CONTENTS E MARINE MAMMAL DENSITY AND DEPTH DISTRIBUTION .................................... E-1 E.1 BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW .............................................................................................. E-1 E.1.1 DENSITY ................................................................................................................................. E-1 E.1.2 DEPTH DISTRIBUTION ......................................................................................................... E-6 E.1.3 DENSITY AND DEPTH DISTRIBUTION COMBINED ....................................................... E-6 E.2 MYSTICETES ............................................................................................................................ E-7 E.2.1 BLUE WHALE, BALAENOPTERA MUSCULUS ................................................................... E-7 E.2.2 FIN WHALE, BALAENOPTERA PHYSALUS ......................................................................... E-8 E.2.3 SEI WHALE, BALAENOPTERA BOREALIS........................................................................... E-8 E.2.4 MINKE WHALE, BALAENOPTERA ACUTOROSTRATA ..................................................... E-8 E.2.5 HUMPBACK WHALE, MEGAPTERA NOVAEANGLIAE ..................................................... E-9 E.2.6 NORTH PACIFIC RIGHT WHALE, EUBALAENA JAPONICA ............................................ E-9 E.2.7 GRAY WHALE, ESCHRICHTIUS -

CONCENTRATIONS and INTERACTIONS of SELECTED ESSENTIAL and NON-ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS in BOWHEAD and BELUGA WHALES of ARCTIC ALASKA Author(S): Victoria M

CONCENTRATIONS AND INTERACTIONS OF SELECTED ESSENTIAL AND NON-ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS IN BOWHEAD AND BELUGA WHALES OF ARCTIC ALASKA Author(s): Victoria M. Woshner, Todd M. O'Hara, Gerald R. Bratton, Robert S. Suydam, and Val R. Beasley Source: Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 37(4):693-710. Published By: Wildlife Disease Association DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-37.4.693 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.7589/0090-3558-37.4.693 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 37(4), 2001, pp. 693–710 ᭧ Wildlife Disease Association 2001 CONCENTRATIONS AND INTERACTIONS OF SELECTED ESSENTIAL AND NON-ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS IN BOWHEAD AND BELUGA WHALES OF ARCTIC ALASKA Victoria M. Woshner,1,2 Todd M. O’Hara,2,4 Gerald R. Bratton,3 Robert S. Suydam,2 and Val R. -

Lesson 3: Researching Whales and Dolphins

Lesson 3: Researching Individual Species -1st grade Page 3-1 Lesson 3: Researching Whales and Dolphins Objective: Students will play a modified game of Bingo to learn information about different types of whales You will need: • Copies of cetacean fact sheets (one copy of each fact sheet) • Bingo sheets (pages 3-3 to 3-32; one per student) and bingo markers (you could use small foam pieces or paper cutouts—anything that the students can use to cover the squares on their bingo sheets; if bingo sheets are laminated, dry erase markers or washable markers could be used. A sheet of “bingo chips” is provided on page 3-33; this can be copied and given to students to cut out and use to cover the squares on their bingo sheets) • Bingo call sheet (page 3-34 and/or page 3-35) • Optional: PowerPoint bingo presentation (there are two versions, corresponding to call sheets 1 and 2) and ability to project this. • Optional: “Only One Ocean” CD (by the Banana Slug String Band) and ability to play the “Cetacea” song. Vocabulary: Cetacea—the group of animals that includes whales and dolphins. Baleen—instead of teeth, some whales have baleen which hangs down in their mouths and lets them catch tiny animals to eat. Beak—the pointy part of a whale or dolphin’s head (usually where its mouth is). Callosities—rough patches of skin on a right whale’s head. These are usually white in color. Cookie cutter shark—a small shark that lives in deep water. It takes circle-shaped bites out of whales’ and dolphins’ skin. -

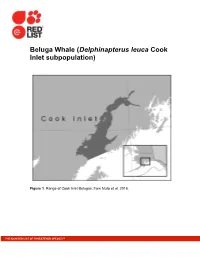

Beluga Whale (Delphinapterus Leuca Cook Inlet Subpopulation)

Beluga Whale (Delphinapterus leuca Cook Inlet subpopulation) Figure 1. Range of Cook Inlet Belugas, from Muto et al. 2016. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Figure 2. Observed distribution of Belugas in Cook Inlet, Alaska, during systematic aerial surveys in June and July during 1978–79 (upper left panel), 1993–97 (upper right panel), 1998–2008 (lower left panel), and 2009–16 (lower right panel). The star is the geographic center of the distribution, the dark gray region is the central 68%, and the striped region is the central 95% of the population. The open circles represent locations and sizes of individual groups of belugas sighted during surveys. The area occupied 2 during 2009-2016 is only 29% of the area occupied during 1978-1979 (from Figure 20 in Shelden et al. 2017; see Shelden et al. 2015 for details of analysis). Figure 3. Abundance estimates and one standard error (SE; vertical line) from aerial surveys of Cook Inlet Belugas in the summer of 1994-2012, 2014, and 2016. The gray line is the trend from 1999-2016 which has a declining rate of -0.4%/yr (SE = 0.6%). Solid squares indicate the years that hunts occurred with digits indicating estimated removals (Shelden et al. 2017). 3 Estimating generation time and the number of mature individuals Critical to the estimation of life history parameters is the ability to accurately estimate the age of individuals, which for Belugas and other toothed cetaceans is typically done by counting growth layer groups (GLGs) in their teeth. For Belugas it has been demonstrated that one GLG is deposited each year (Stewart et al.