Spasticity Outcome Measures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drugs to Avoid in Patients with Dementia

Detail-Document #240510 -This Detail-Document accompanies the related article published in- PHARMACIST’S LETTER / PRESCRIBER’S LETTER May 2008 ~ Volume 24 ~ Number 240510 Drugs To Avoid in Patients with Dementia Elderly people with dementia often tolerate drugs less favorably than healthy older adults. Reasons include increased sensitivity to certain side effects, difficulty with adhering to drug regimens, and decreased ability to recognize and report adverse events. Elderly adults with dementia are also more prone than healthy older persons to develop drug-induced cognitive impairment.1 Medications with strong anticholinergic (AC) side effects, such as sedating antihistamines, are well- known for causing acute cognitive impairment in people with dementia.1-3 Anticholinergic-like effects, such as urinary retention and dry mouth, have also been identified in drugs not typically associated with major AC side effects (e.g., narcotics, benzodiazepines).3 These drugs are also important causes of acute confusional states. Factors that may determine whether a patient will develop cognitive impairment when exposed to ACs include: 1) total AC load (determined by number of AC drugs and dose of agents utilized), 2) baseline cognitive function, and 3) individual patient pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic features (e.g., renal/hepatic function).1 Evidence suggests that impairment of cholinergic transmission plays a key role in the development of Alzheimer’s dementia. Thus, the development of the cholinesterase inhibitors (CIs). When used appropriately, the CIs (donepezil [Aricept], rivastigmine [Exelon], and galantamine [Razadyne, Reminyl in Canada]) may slow the decline of cognitive and functional impairment in people with dementia. In order to achieve maximum therapeutic effect, they ideally should not be used in combination with ACs, agents known to have an opposing mechanism of action.1,2 Roe et al studied AC use in 836 elderly patients.1 Use of ACs was found to be greater in patients with probable dementia than healthy older adults (33% vs. -

Tizanidine Brands: Zanaflex®

Medication Information Sheet Tizanidine brands: Zanaflex® Medications are only ONE part of a successful treatment plan. They are appropriate when they provide benefit, improve function and have either no or mild, manageable side effects. Importantly, medications (even if natural) are chemical substances not expected in the body, and as such have side effects. Some of the side effects might be unknown. The use of medications/drugs for any purpose requires patient consent. This practice does NOT require a patient to use any medication. Information & potential benefits Tizanidine is a medication that helps with muscle spasms and musculoskeletal pain syndromes; there is evidence that it helps neuropathic and musculoskeletal pain through alpha‐2‐receptor activity. Studies have shown Zanaflex helpful for neuropathic pain and some types of headache. It is currently FDA approved for muscle spasticity. Potential risks and side effects Tizanidine should be used carefully in cases of liver or kidney disease, low blood pressure, or heart conduction problems (QT interval problems). It should not be used with Luvox or with the antibiotic Cipro (ciprofloxacin). There are many other drugs that can interact with Tizanadine. In addition to the standard side effects listed in the disclaimer, common side effects or Zanaflex include dry mouth, sleepiness, dizziness, asthenia, infection, constipation, urinary frequency, flu‐like feeling, low blood pressure, more spasms, sore throat and runny nose. More serious side effects include liver damage, severe slowing of the heart beat and hallucinations. Tizanidine occasionally causes liver injury. In controlled clinical studies, approximately 5% of patients treated with tizanidine had non‐serious elevations of liver function tests. -

Paper Clip—High Risk Medications

You belong. PAPER CLIP—HIGH RISK MEDICATIONS Description: Some medications may be risky for people over 65 years of age and there may be safer drug choices to treat some conditions. It is recommended that medications are reviewed regularly with your providers/prescriber to ensure patient safety. Condition Treated Current Medication(s)-High Risk Safer Alternatives to Consider Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs), Nitrofurantoin Bactrim (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) or recurrent UTIs, or Prophylaxis (Macrobid, or Macrodantin) Trimpex/Proloprim/Primsol (trimethoprim) Allergies Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Xyzal (Levocetirizine) Anxiety Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Buspar (Buspirone), Paxil (Paroxetine), Effexor (Venlafaxine) Parkinson’s Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Symmetrel (Amantadine), Sinemet (Carbidopa/levodopa), Selegiline (Eldepryl) Motion Sickness Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Antivert (Meclizine) Nausea & Vomiting Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Zofran (Ondansetron) Insomnia Hydroxyzine (Vistaril, Atarax) Ramelteon (Rozerem), Doxepin (Silenor) Chronic Insomnia Eszopiclone (Lunesta) Ramelteon (Rozerem), Doxepin (Silenor) Chronic Insomnia Zolpidem (Ambien) Ramelteon (Rozerem), Doxepin (Silenor) Chronic Insomnia Zaleplon (Sonata) Ramelteon (Rozerem), Doxepin (Silenor) Muscle Relaxants Cyclobenazprine (Flexeril, Amrix) NSAIDs (Ibuprofen, naproxen) or Hydrocodone Codeine Tramadol (Ultram) Baclofen (Lioresal) Tizanidine (Zanaflex) Migraine Prophylaxis Elavil (Amitriptyline) Propranolol (Inderal), Timolol (Blocadren), Topiramate (Topamax), -

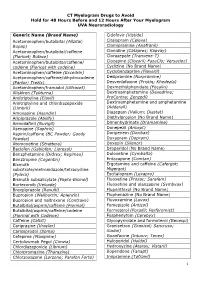

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

Use of Amitriptyline for the Treatment of Chronic Tension-Type Headache

Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008 Sep1;13(9):E567-72. Amitriptyline and chronic tension-type headache Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008 Sep1;13(9):E567-72. Amitriptyline and chronic tension-type headache Publication Types: Review Use of amitriptyline for the treatment of chronic tension-type headache. Review of the literature Eulalia Torrente Castells 1, Eduardo Vázquez Delgado 2, Cosme Gay Escoda 3 (1) Odontóloga. Residente del Máster de Cirugía Bucal e Implantología Bucofacial. Facultad de Odontología de la Universidad de Barcelona (2) Odontólogo. Profesor Asociado de Cirugía Bucal. Profesor responsable de la Unidad de Patología de la ATM y Dolor Bucofacial del Máster de Cirugía Bucal e Implantología Bucofacial. Facultad de Odontología de la Universidad de Barcelona. Especialista de la Unidad de Patología de la ATM y Dolor Bucofacial del Centro Médico Teknon. Barcelona (3) Médico-Estomatólogo y Cirujano Maxilofacial. Catedrático de Patología Quirúrgica Bucal y Maxilofacial. Director del Máster de Cirugía Bucal e Implantología Bucofacial. Facultad de Odontología de la Universidad de Barcelona. Co-director de la Unidad de Patología de la ATM y Dolor Bucofacial del Centro Médico Teknon. Barcelona Correspondence: Prof. Cosme Gay Escoda Centro Médico Teknon C/Vilana nº 12 08022 Barcelona E-mail: [email protected] Torrente-Castells E, Vázquez-Delgado E, Gay-Escoda C. Use of amitrip- Received: 28/09/2007 tyline for the treatment of chronic tension-type headache. Review of the Accepted: 11/07/2008 literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008 Sep1;13(9):E567-72. © Medicina Oral S. L. C.I.F. B 96689336 - ISSN 1698-6946 Indexed in: http://www.medicinaoral.com/medoralfree01/v13i9/medoralv13i9p567.pdf -Index Medicus / MEDLINE / PubMed -EMBASE, Excerpta Medica -SCOPUS -Indice Médico Español -IBECS Abstract Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant, considered the treatment of choice for different types of chronic pain, including chronic myofascial pain. -

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information No

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information No. 242 December 2007 Table of Contents 1. Important Safety Information ·························································3 .1. Atorvastatin Calcium Hydrate ······························································3 .2. Tizanidine Hydrochloride ····································································· 6 .3. Thiamazole ··························································································8 2. Revision of PRECAUTIONS (No. 192) Amitriptyline Hydrochloride and 11 others·······································13 3. List of products subject to Early Post-marketing Phase Vigilance ·········································································································· 21 This Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Safety Information (PMDSI) is issued based on safety information collected by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. It is intended to facilitate safer use of pharmaceuticals and medical devices by healthcare providers. PMDSI is available on the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency website (http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/index.html) and on the MHLW website (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/) (Japanese only). Published by Translated by Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Pharmaceutical and Food Safety Bureau, Office of Safety, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency 1-2-2 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, -

Alternatives to the Most-Prescribed HMSA High-Risk Medication (HRM) List 2018 Items in Bold Are on the 2018 HMSA Formulary

Alternatives to the Most-prescribed HMSA High-risk Medication (HRM) List 2018 Items in bold are on the 2018 HMSA formulary. Drugs to Avoid Concern Possible Alternatives eszopiclone Cognitive impairment, delirium, unsteady gait, Nonpharmacologic therapy (e.g., avoid daytime naps and caffeinated zolpidem syncope, falls, motor vehicle accidents, beverages, and other sleep hygiene techniques), assess for treatment zaleplon fractures, sleep behaviors, and anterograde for depression and anxiety. amnesia with minimal improvement in sleep latency and duration. methyldopa High risk of adverse CNS effects; may cause Consider thiazide diuretics (HCTZ, indapamide, metolazone); ACEI bradycardia and orthostatic hypotension. (benazepril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, lisinopril, quinapril, ramipril, trandolapril); ARBs (irbesartan, losartan, valsartan); long- digoxin In heart failure, high dosages are associated acting dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, >0.125 mg/day with no additional benefit; decreased clearance felodipine, nifedipine ER). may lead to risk of toxic effects. Consider rate control before rhythm control; monitor SCr and digoxin levels (free digoxin level). nitrofurantoin Potential for pulmonary toxicity; hepatotoxicity For uncomplicated cystitis: trimethoprim or TMP-SMX. Consider and peripheral neuropathy with long-term use. patient's allergy history, renal adjustment, and other risk factors and local Avoid in patients with CrCl <30 mL/min due to resistance patterns. inadequate drug concentration in the urine. amitriptyline Highly anticholinergic, (i.e., constipation, dry For depression: SSRI (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, clomipramine mouth), cognitive impairment, delirium, sedation sertraline), SNRI (desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, venlafaxine), or others doxepin >6 mg/day orthostatic hypotension. (buproprion, mirtazapine) can be selected based on adverse effect imipramine profiles, cost, and patient preferences. For neuropathic pain: gabapentin, duloxetine, pregabalin. -

Opioid Initiative Wave I – Treating Opioid-Use Disorder in the ED Part 1 Presenter

Opioid Initiative Wave I – Treating Opioid-Use Disorder in the ED Part 1 Presenter Eric Ketcham, MD, MBA Reuben J. Strayer, MD emergency department management of the patient with opioid withdrawal OD is #1 cause of death of americans under age 50 1999-2016: more than 600,000 overdose deaths I have chronic pain and need meds I overdosed and got naloxone by EMS I overdosed and am now in cardiac arrest I inject heroin and now have cellulitis / endocarditis I have complications from HIV or Hep C I sell sex to get drugs and now have an STI I’m homeless I’ve been arrested I’ve been assaulted I’m addicted to narcotics and am now in withdrawal I have a problem and need help I’m dope sick and can’t stop vomiting opioid withdrawal case 27F no PMH, visiting from LA opioid addict, prefers fentanyl arrives at 5p severe body aches, restlessness, vomiting,diarrhea 4 IV start attempts over 30 minutes,conflict++ receives, over 11 hours in the ED: Ondansetron 8mg IV x2: 16mg IV Promethazine 25mg IVPB x2: 50mg IV Clonidine 0.2mg PO x 4 doses: 0.8mg PO Lorazepam 2mg IV x 3 doses: 6mg IV Haloperidol 5mg IV x 2 doses: 10mg IV Normal Saline 2 liters IV. Discharged with promethazine and clonidine prescription opioid withdrawal case 4 IV start attempts over 30 minutes,conflict++ receives, over 11 hours in the ED: Ondansetron 8mg IV x2: 16mg IV Promethazine 25mg IVPB x2: 50mg IV Clonidine 0.2mg PO x 4 doses: 0.8mg PO Lorazepam 2mg IV x 3 doses: 6mg IV Haloperidol 5mg IV x 2 doses: 10mg IV Normal Saline 2 liters IV. -

Evidence Tables

Evidence Table 1. Included systematic reviews and meta-analyses of skeletal muscle relaxants in patients with spasticity Time period covered Funding Author and sources used in Exclusion source and Method of Characteristics of identified Year Aims literature search Eligibility criteria criteria role appraisal articles Systematic reviews Shakespeare Assess the absolute Through February Double-blind, RCTs <7 days None Independently 36/157 157 identified studies met 2001 and comparative 2001 (for MEDLINE) (either placebo- duration abstracted by inclusion criteria efficacy and controlled or two reviewers tolerability of anti- MEDLINE, EMBASE, comparative studies) and findings 23 placebo-controlled trials (5 oral spasticity agents in reference lists, summarized baclofen, 4 dantrolene, 3 tizanidine, multiple sclerosis personal 3 botulinum toxin, 2 vigabitrin, 1 (MS) patients communications, drug prazepam, 3 progabide, 1 brolitene, manufacturers, 1 L-threonine) manual searches of journals, collaborative 13 head-to-head trials met selection MS trial registry, criteria (7 tizanidine vs. baclofen; 1 Cochrane database, baclofen vs. diazepam, 1 diazepam National Health vs. dantrolene, 2 ketazolam vs. Service National diazepam, 2 tizanidine vs. Research Register diazepam) 1359 patients overall Taricco Assess the Through 1998 All parallel and RCTs with None Data 9 of 53 studies met inclusion criteria 2000 effectiveness and crossover RCTs <50% of independently (1 oral baclofen, 4 intrathecal safety of drugs for CCTR, MEDLINE, including SCI patients with abstracted by baclofen, 1 amytal and valium, 1 the treatment of EMBASE, CINAHL patients with "severe SCI two reviewers gabapentin, 1 clonidine, 1 long term spasticity spasticity" using data tizanidine) in spinal cord injury extraction form patients 8 crossover studies, 1 parallel group trial 218 patients overall RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial; CCTR = Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry; CINAHL = Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health; SCI = Spinal Cord Injury 62 Evidence Table 1. -

The Effects of Antimuscarinic Treatment on the Cognition of Spinal Cord

Spinal Cord (2018) 56, 22–27 & 2018 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/18 www.nature.com/sc ORIGINAL ARTICLE The effects of antimuscarinic treatment on the cognition of spinal cord injured individuals with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction: a prospective controlled before-and- after study J Krebs1, A Scheel-Sailer2, R Oertli3 and J Pannek4 Study design: Prospective controlled before-and-after study. Objectives: To investigate the effects of antimuscarinic treatment of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction on the cognition of individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) during the early post-acute phase. Setting: Single SCI rehabilitation center. Methods: Patients with acute traumatic SCI admitted for primary rehabilitation from 2011 to 2015 were screened for study enrollment. Study participants underwent baseline neuropsychological assessments prior to their first urodynamic evaluation (6–8 weeks after SCI). Individuals suffering from neurogenic detrusor overactivity received antimuscarinic treatment, and those not requiring antimuscarinic treatment constituted the control group. The neuropsychological follow-up assessment was carried out 3 months after the baseline assessment. The effects of group and time on the neuropsychological parameters were investigated. Results: The data of 29 individuals were evaluated (control group 19, antimuscarinic group 10). The group had a significant (P ≤ 0.033) effect on immediate recall, attention ability and perseveration. In the control group, individuals performed significantly (P ≤ 0.05) better in immediate recall both at baseline (percentile rank 40, 95% CI 21–86 versus 17, 95% CI 4–74) and follow-up (percentile rank 40, 95% CI 27–74 versus 16, 95% CI 2–74). The time had a significant (P ≤ 0.04) effect on attention ability, processing speed, word fluency and visuospatial performance. -

High-Risk Medication Pocket Guide

High-Risk Medication Pocket Guide Therapeutic Class High-Risk Medication Potential Risks Alternative Medication Option Antihistamines Brompheniramine, Carbinoxamine, Highly anticholinergic (can cause dry mouth, flushing, dry Allergies: Cetirizine, Fexofenadine, Loratadine, Chlorpheniramine, Clemastine, skin, confusion, or difficulty urinating); Sedation. Levocetirizine (as a single agent or as Cyproheptadine, Dexbrompheniramine, Anxiety: Buspirone, SSRIs (Fluoxetine, Paroxetine), part of a combination Dexchlorpheniramine, Diphenhydramine SNRIs (Venlafaxine, Cymbalta) product) - excludes (oral), Doxylamine, Hydroxyzine, OTC products Promethazine, Triprolidine Insomnia: Melatonin, low-dose Trazodone Anti-Infectives Nitrofurantoin (when cumulative day supply Potential for pulmonary toxicity or peripheral neuropathy Infection: Ciprofloxacin, Trimethoprim/ is >90 days during plan year) (numbness, tingling, or pain in the hands, feet, or toes. Sulfamethoxazole, Amoxicillin/Clavulanate, Muscle weakness. Cephalexin Difficulty walking and/or problems with balance or coordination). Antiparkinson Agents Benztropine (oral), Trihexyphenidyl Highly anticholinergic (can cause dry mouth, flushing, Parkinson Disease: Selegiline, dry skin, confusion, or difficulty urinating); Carbidopa/Levodopa, Ropinirole, Pramipexole, Not recommended for prevention of extrapyramidal Entacapone symptoms with antipsychotics due to potential Antipsychotic induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms: hallucinations. Quetiapine, Clozapine Antipsychotics Thioridazine Highly anticholinergic