Graph-Based Classification of Intestinal Glands in Colorectal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digestive System Small and Large Intestines Lec. 21

Digestive System Small and Large Intestines Lec. 21 Histology Second year L. Hadeel Kamil 1 Small Intestine • The small intestine is a long, convoluted tube about 5 to 7 m long; it is the longest section of the digestive tract. The small intestine extends from the junction with the stomach to join with the large intestine or colon. For descriptive purposes, the small intestine is divided into three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Although the microscopic differences among these three segments are minor, they allow for identification of the segments. The main function of the small intestine is the digestion of gastric contents and absorption of nutrients into blood capillaries and lymphatic lacteals. 2 Surface Modifications of Small Intestine for Absorption • The mucosa of the small intestine exhibits specialized structural modifications that increase the cellular surface areas for absorption of nutrients and fluids. These modifications include the plicae circulares, villi, and microvilli. In contrast to the rugae of stomach, the plicae circulares are permanent spiral folds or elevations of the mucosa ( with a submucosal core) that extend into the intestinal lumen. The plicae circulares are most prominent in the proximal portion of the small intestine, where most absorption takes place; they decrease in prominence toward the ileum. Villi are permanent fingerlike projections of lamina propria of the mucosa that extend into the intestinal lumen. They are covered by simple columnar epithelium and are also more prominent in the proximal portion of the small intestine. The height of the villi decreases toward the ileum of the small intestine. The connective tissue core of each villus contains a lymphatic capillary called a lacteal, blood capillaries, and individual strands of smooth muscles 3 • Each villus has a core of lamina propria that is normally filled with blood vessels, lymphatic capillaries, nerves, smooth muscle, and loose irregular connective tissue. -

The Digestive System

69 chapter four THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM The digestive system is structurally divided into two main parts: a long, winding tube that carries food through its length, and a series of supportive organs outside of the tube. The long tube is called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The GI tract extends from the mouth to the anus, and consists of the mouth, or oral cavity, the pharynx, the esophagus, the stomach, the small intestine, and the large intes- tine. It is here that the functions of mechanical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption of nutrients and water, and release of solid waste material take place. The supportive organs that lie outside the GI tract are known as accessory organs, and include the teeth, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. Because most organs of the digestive system lie within body cavities, you will perform a dissection procedure that exposes the cavities before you begin identifying individual organs. You will also observe the cavities and their associated membranes before proceeding with your study of the digestive system. EXPOSING THE BODY CAVITIES should feel like the wall of a stretched balloon. With your skinned cat on its dorsal side, examine the cutting lines shown in Figure 4.1 and plan 2. Extend the cut laterally in both direc- out your dissection. Note that the numbers tions, roughly 4 inches, still working with indicate the sequence of the cutting procedure. your scissors. Cut in a curved pattern as Palpate the long, bony sternum and the softer, shown in Figure 4.1, which follows the cartilaginous xiphoid process to find the ventral contour of the diaphragm. -

Nomina Histologica Veterinaria, First Edition

NOMINA HISTOLOGICA VETERINARIA Submitted by the International Committee on Veterinary Histological Nomenclature (ICVHN) to the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists Published on the website of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists www.wava-amav.org 2017 CONTENTS Introduction i Principles of term construction in N.H.V. iii Cytologia – Cytology 1 Textus epithelialis – Epithelial tissue 10 Textus connectivus – Connective tissue 13 Sanguis et Lympha – Blood and Lymph 17 Textus muscularis – Muscle tissue 19 Textus nervosus – Nerve tissue 20 Splanchnologia – Viscera 23 Systema digestorium – Digestive system 24 Systema respiratorium – Respiratory system 32 Systema urinarium – Urinary system 35 Organa genitalia masculina – Male genital system 38 Organa genitalia feminina – Female genital system 42 Systema endocrinum – Endocrine system 45 Systema cardiovasculare et lymphaticum [Angiologia] – Cardiovascular and lymphatic system 47 Systema nervosum – Nervous system 52 Receptores sensorii et Organa sensuum – Sensory receptors and Sense organs 58 Integumentum – Integument 64 INTRODUCTION The preparations leading to the publication of the present first edition of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria has a long history spanning more than 50 years. Under the auspices of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists (W.A.V.A.), the International Committee on Veterinary Anatomical Nomenclature (I.C.V.A.N.) appointed in Giessen, 1965, a Subcommittee on Histology and Embryology which started a working relation with the Subcommittee on Histology of the former International Anatomical Nomenclature Committee. In Mexico City, 1971, this Subcommittee presented a document entitled Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft as a basis for the continued work of the newly-appointed Subcommittee on Histological Nomenclature. This resulted in the editing of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft II (Toulouse, 1974), followed by preparations for publication of a Nomina Histologica Veterinaria. -

Digestive Tracttract

Digestive System ——DigestiveDigestive TractTract Dept.Dept. ofof HistologyHistology andand EmbryologyEmbryology 周莉周莉 教授教授 Introduction of digestive system * a long tube extending from the mouth to the anus, and associated with glands. * its main function: -digestion: physical/chemical -absorption * three major sections -the oral cavity including oropharynx -the tubular digestive tract -the major digestive glands: salivary glands, pancreas, liver, the general structure of the digestive tract Ⅰ. General Structure of the Digestive Tract 1. mucosa (1) epithelium: stratified squamous epithelium in two ends, the rest simple columnar epithelium (2) lamina propria: loose connective tissue rich in glands, lymphoid tissue and blood vessel (3) muscularis mucosa: thin layer of smooth muscle cells (innerinner circularcircular andand outerouter longitudinallongitudinal )) 2.2. SubmucosaSubmucosa:: CTCT,, esophagealesophageal glandsglands andand duodenumduodenum glandsglands,, submucosa(Meissnersubmucosa(Meissner)) nervenerve plexusplexus 3.3. muscularismuscularis:: innerinner circularcircular andand outerouter longitudinallongitudinal smoothsmooth musclemuscle cellscells myentericmyenteric nervenerve plexusplexus 4.4. Adventitia:Adventitia: fibrosafibrosa oror serosaserosa Ⅱ. The Oral Cavity 1.1. GeneralGeneral StructureStructure ofof MucosaMucosa ofof OralOral CavityCavity 2.2. tongue:tongue: mucosamucosa andand tonguetongue musclemuscle (( skeletalskeletal muscle)muscle) linguallingual papillaepapillae (1)(1) filiformfiliform papillaepapillae (2)(2) -

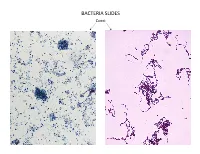

Bacteria Slides

BACTERIA SLIDES Cocci Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES _______________ __ BACTERIA SLIDES Spirilla BACTERIA SLIDES ___________________ _____ BACTERIA SLIDES Bacillus BACTERIA SLIDES ________________ _ LUNG SLIDE Bronchiole Lumen Alveolar Sac Alveoli Alveolar Duct LUNG SLIDE SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL Superior Concha Auditory Tube Middle Concha Opening Inferior Concha Nasal Cavity Internal Nare External Nare Hard Palate Pharyngeal Oral Cavity Tonsils Tongue Nasopharynx Soft Palate Oropharynx Uvula Laryngopharynx Palatine Tonsils Lingual Tonsils Epiglottis False Vocal Cords True Vocal Cords Esophagus Thyroid Cartilage Trachea Cricoid Cartilage SAGITTAL SECTION OF HUMAN HEAD MODEL LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View Hyoid Bone Superior Horn Thyroid Cartilage Inferior Horn Thyroid Gland Cricoid Cartilage Trachea Tracheal Rings LARYNX MODEL Posterior View Epiglottis Hyoid Bone Vocal Cords Epiglottis Corniculate Cartilage Arytenoid Cartilage Cricoid Cartilage Thyroid Gland Parathyroid Glands LARYNX MODEL Side View Anterior View ____________ _ ____________ _______ ______________ _____ _____________ ____________________ _____ ______________ _____ _________ _________ ____________ _______ LARYNX MODEL Posterior View HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Larynx Tracheal Rings Found on the Trachea Left Superior Lobe Left Inferior Lobe Heart Right Superior Lobe Right Middle Lobe Right Inferior Lobe Diaphragm HUMAN HEART & LUNGS MODEL Hilum (curvature where blood vessels enter lungs) Carina Pulmonary Arteries (Blue) Pulmonary Veins (Red) Bronchioles Apex (points -

Clonal Transitions and Phenotypic Evolution in Barrett Esophagus

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.31.21252894; this version posted April 6, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Clonal transitions and phenotypic evolution in Barrett esophagus Short title: Phenotypic evolution in Barrett esophagus James A Evans1*, Emanuela Carlotti1*, Meng-Lay Lin1, Richard J Hackett1, Adam Passman1, , Lorna Dunn2§, George Elia1, Ross J Porter3#, Mairi H McClean3**, Frances Hughes4, Joanne ChinAleong5, Philip Woodland6, Sean L Preston6, S Michael Griffin2,7, Laurence Lovat8, Manuel Rodriguez-Justo9, Nicholas A Wright1, Marnix Jansen10,11 & Stuart AC McDonald1 1Clonal dynamics in epithelia laboratory, 3Epithelial stem cell laboratory, Centre for Cancer Genomics and Computational Biology, Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK 2Nothern Institute for Cancer Research, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK 3Department of Gastroenterology, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK 4Department of Surgery, 5Histopathology, 6Endoscopy Unit, Barts Health NHS Trust, Royal London Hospital, London, UK 7Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK 8Oeosophagogastric Disorders Centre, Department of Gastroenterology, University College London Hospitals, London, UK 9Research Department of Tissue and Energy, UCL Division of Surgical and Interventional Science, University College London -

Immunohistochemical Localization of Carbonic Anhydrase Isoenzymes in Salivary Gland and Intestine in Adult and Suckling Pigs

FULL PAPER Anatomy Immunohistochemical Localization of Carbonic Anhydrase Isoenzymes in Salivary Gland and Intestine in Adult and Suckling Pigs Tomoko AMASAKI1), Hajime AMASAKI2)*, Jun NAGASAO3), Nobutsune ICHIHARA1), Masao ASARI1), Toshiho NISHITA1), Kazumi TANIGUCHI3) and Ken-ichiro MUTOH3) 1)Department of Anatomy and Physiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, Azabu University, Sagamihara-shi 229–8501, 2)Department of Veterinary Anatomy, Nippon Veterinary and Animal Science University, Musashino-shi 180–8602 and 3)Department of Veterinary Anatomy, School of Veterinary Medicune and Animal Sciences, Kitasato University, Towada-shi 034–8628, Japan (Received 30 December 2000/Accepted 17 May 2001) ABSTRACT. Localizations of carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes (CA I, CA II and CA III) were investigated immunohistochemically in the salivary glands and intestine of mature and suckling pigs. Carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes were not detected in the salivary glands of sucklings, but were present in the adult. Bicarbonate ion in saliva might be important for the digestion of solid foods in mature pigs, but unnecessary for the digestion of milk in sucklings. Expressions of CAI and CAII were detected strongly in the large intestine of the adult and sucklings, and faintly only at duodenum in the small intestine. CA I and CA II isoenzymes in the large intestine may be involved, at least in part, in ion absorption and water metabolism during digestion and absorption of milk in suckling pigs. In addition, CA I and CA II expression in the duodenal villus enterocyte may support the process of bicarbonate absorption in the duodenum. KEY WORDS: adult and suckling pig, carbonic anhydrase, intestine, salivary gland. J. Vet. -

Gross and Microanatomy of the Digestive Tract and Pancreas of the Channel Catfish, Ictalurus Punctatus

THE GROSS AND MICROANATOMY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT AND PANCREAS OF THE CHANNEL CATFISH, ICTALURUS PUNCTATUS by RONALD LESTER GAMMON B. S. , Kansas State University, 1968 B. S. , Kansas State University, 1970 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Divis ion of Biology KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1970 Approved by: mm£Major Professor L-2> i i M6. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 I NTRODUCT I ON REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 2 G ros s Ana tomy 2 Mouth 2 Pha rynx k Esophagus 6 Stomach 8 Intestine 9 Histological Characteristics 11 Buccal Cavity 11 Esophagus 14 Stomach 18 Intestine 21 MATERIALS AND METHODS 23 RESULTS 26 Gross Anatomy 26 Oral Cavity and Pharynx 26 Esophagus 27 Stomach 27 Intestine 28 Histological Characteristics 28 Esophagus 28 Stomach 32 1 1 1 Intestine 36 Pa nc rea s 39 Dl SCUSS ION H ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 50 LITERATURE CITED 51 INTRODUCTION catfish, During recent years Ictalurus punctatus , the channel has become an economically important species for food and for sport. Sport fishermen have increasingly sought the channel catfish because these fish grow large enough to be fun for the sportsman to catch and the fish caught have good flavor. Consequently, many federal, state, and private lakes are stocked regularly. The use of channel catfish as a source of protein for human consumption has made the rearing of channel catfish an important industry. Since this fish is easy to raise and feed, its importance as a human foodstuff seems likely to increase in the future. -

5.Small Intestine

Small intestine Divided into three parts: duodenum jejunum ileum Function: *digestion *absorption *secreted certain hormones Plicae circulares : a fold of mucosa and submucosa in the lumen of digestive tract Intestinal villi *small finger- or leaf-like projection of the mucosa, found only in the small intestine; *varying in the form and height in different region *being covered by epith. *having a core of lamina propria with capillary network, a central lacteal and few smooth muscle fibers. microvilli: the minute projections (1 µm long and about 0.1 µm wide) of cell membranes The inner surface of small intestine can be greatly enlarged by: * plicae circularesX3. * villiX 10. * microvilliX 20. jejunum H.E. staining 模式图 Core of villus epithelium villus Smooth muscle gland Artery Lacteal vein Longitudinal section of small intestine 5.1.1 Epithelium * Simple columnar epith. 5.1.2 lamina propria * C.T. containing lymphatic tissue, solitary lymphatic nodule, intestinal glands. * protrudes into the lumen together with epithelium to form villi. Small intestinal gland *infolding the epithelium to the lamina propria at the base of villus *types of cells: Goblet c. Absorptive c. Paneth c Stem c. Endocrine c. absorptive cells * a tall columnar cell with ovoid nucleus located toward the base. * striated border formed by closely packed, parallel microvilli * tight junction complex at the periphery and near the apex * function as absorption of sugar, amino acid and lipid. * involving in secretion of IgAand producing enterokinase goblet cells EM of goblet cells { The RER is present mainly in the basal portion of the cell { the cell apex is filled with light secretory granules (SG) some of which are being discharged. -

PANCREAS, LIVER, SMALL INTESTINE and LARGE INTESTINE PANCREAS Anatomy of Pancreas the Pancreas Is a Pale Grey Gland Weighing About 60 Grams

PANCREAS, LIVER, SMALL INTESTINE AND LARGE INTESTINE PANCREAS Anatomy of pancreas The pancreas is a pale grey gland weighing about 60 grams. It is about 12 to 15 cm long and is situated in the epigastric and left hypochondriac regions of the abdominal cavity. • It consists of a broad head (in the curve of the duodenum), a body (behind the stomach )and a narrow tail(lies in front of the left kidney and just reaches the spleen). • The abdominal aorta and the inferior vena cava lie behind the gland. • Pancreas is a dual organ having two functions, namely endocrine function and exocrine function. -Endocrine function is concerned with the production of hormones. -Exocrine function is concerned with the secretion of digestive juice called pancreatic juice. The exocrine pancreas This consists of a large number of lobules made up of small alveoli, the walls of which consist of secretory cells. Each lobule is drained by a tiny duct and these unite eventually to form the pancreatic duct, which extends the whole length of the gland and opens into the duodenum. Just before entering the duodenum the pancreatic duct joins the common bile duct to form the hepatopancreatic ampulla. The duodenal opening of the ampulla is controlled by the hepatopancreatic sphincter (of Oddi). The endocrine pancreas Distributed throughout the gland are groups of specialized cells called the pancreatic islets (of Langerhans). The islets have no ducts so the hormones diffuse directly into the blood. The islets have 4 types of cell, which produce different hormones. Alpha cells (glucagon), beta cells (insulin), delta cells (somatostatin) and PP cells (pancreatic polypeptide). -

46 Small Intestine

Small Intestine The small intestine extends between the stomach and colon and is divided into the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Although there are minor microscopic differences among these subdivisions, all have the same basic organization as the rest of the digestive tube - mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa or adventitia. The transition from one segment to another is gradual. The proximal 12 inches of its length is generally considered duodenum, the remaining proximal two-fifths jejunum and the distal three-fifths ileum. The small intestine moves chyme from the stomach to the colon and completes the digestive processes by adding enzymes secreted by the intestinal mucosa and accessory glands (liver and pancreas). Its primary function, however, is absorption. Approximately 8 to 9 liters of fluid enters the small intestine on a daily basis. Food and liquid intake represents 1-2 liters of this volume the remainder coming from endogenous sources such as salivary, gastric, intestinal, pancreatic, and biliary secretions. Of this volume 6-7 liters is absorbed in the small intestine with only 1-2 liters entering the colon the majority of which is absorbed at this location. Only as very small amount of fluid is evacuated in the stool. The majority of water is absorbed passively in the gut and is largely dependent on an osmotic gradient. Specializations for Absorption Three specializations - plicae circulares, intestinal villi, and microvilli - markedly increase the surface area of the intestinal mucosa to enhance the absorptive process. It is estimated that these morphological features provide an absorptive surface area of 200 M2. Plicae circulares are large, permanent folds that consist of the intestinal mucosa and a core of submucosa. -

Anatomical and Histochemical Studies of the Large Intestine of the African Giant Rat ( Cricetomysgambianus -Water House)- I

Available online a t www.aexpbio.com RESEARCH ARTICLE Annals of Experimental Biology 2015, 3 (4):27-35 ISSN : 2348-1935 Anatomical and Histochemical Studies of the Large Intestine of the African Giant rat ( Cricetomysgambianus -Water house)- I Nzalak, J.O*1, Onyeanusi, B.I 1, Wanmi, N2, Maidawa, S.M 1 1Department of Veterinary Anatomy, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria. 2Department of Veterinary Anatomy, University of Agriculture Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria *Corresponding e-mail: [email protected] _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Forty African giant rats (AGRs), (Cricetomysgambianus-Waterhouse) were used for morphometric, morphologic, histologic and histochemical studies. The rats were sacrificed according to the method of Adeyemo and Oke (1990) and the different segments of the large intestine (caecum, colon and rectum) were weighed, measured and photographs taken. Transverse sections of the different segments of the large intestine were stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin for normal histological studies. For Histochemical studies, the transverse sections were stained with Alcian Blue (AB), Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) and Alcian Blue-Periodic Acid Schiff (AB-PAS) to determine their nature of secretions. The large intestine was observed to have a mean weight and length of 19.98 ± 0.39 g and 75.57 ± 1.00 cm respectively. The large intestine was observed to be made up of the caecum, colon and rectum, and all had similar basic histological structures, none of them had villi. The mucosal surfaces were smooth with goblet cells. Histochemical studies of the large intestine showed a positive response to AB, PAS, and AB-PAS. The thickening of the tunica muscularis of the colon and rectum was correlated with the temporary storage and expulsion of fecal materials.