Building Kites David Brian Anderson University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 2021 at 10:00 AM

www.reddingauction.com 1085 Table Rock Road, Gettysburg, PA PH: 717-334-6941 Pennsylvania's Largest No Buyers Premium Gun Auction Service Your Professional FireArms Specialists With 127+ Combined Years of Experience Striving to Put Our Clients First & Achieving Highest Prices Realized as Possible! NO RESERVE – NO BUYERS PREMIUM If You Are Interested in Selling Your Items in an Upcoming Auction, Email [email protected] or Call 717- 334-6941 to Speak to Someone Personally. We Are Consistently Bringing Higher Prices Realized Than Other Local Auction Services Due to Not Employing a Buyer’s Premium (Buyer’s Penalty). Also, We Consistently Market Our Sales Nationally with Actual Content For Longer Periods of Time Than Other Auction Services. SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 2021 at 10:00 AM PLEASE NOTE: -- THIS IS YOUR ITEMIZED LISTING FOR THIS PARTICULAR AUCTION PLEASE BRING IT WITH YOU WHEN ATTENDING Abbreviation Key for Ammo Lots: NIB – New in Box WTOC – Wrapped at Time of Cataloging (RAS Did Not Unwrap the Lots With This Designation in Order to Verify the Correctness & Round Count. We depend on our consignor’s honesty and integrity when describing sealed boxes. RAS Will Offer No Warranties or No Guarantees Regarding Count or the Contents Inside of These Boxes) Any firearms with a “R” after the lot number means it is a registrable firearm. Any firearms without the “R” is an antique & Mfg. Pre-1898 meaning No registration is required. Lot #: 1. Winchester – No. W-600 Caged Copper Room Heater w/Cord – 12½” Wide 16” High w/Gray Base (Excellent Label) 2. Winchester-Western – “Sporting Arms & Ammunition” 16” Hexagon Shaped Wall Clock – Mfg. -

Kitchen? the Heart and Soul of Every Restaurant Resides in the Kitchen

What's Cookin' in the Kitchen? The heart and soul of every restaurant resides in the kitchen. From prep to storage and all points in-between, the kitchen is the life force of every dining establishment. Creative culinary gadgets and modern innovations have made kitchen work easier and given way to new methods of cooking and serving. A well-stocked kitchen isn't just about the food, the manner in which the meal is prepared and served is as important as the ingredients used in every recipe. RITZ® 685° Silicone Heat Protection • Flame and heat resistant up to 685°F • Unique tread design for better grip • Oven mitts feature 100% cotton interior • Dishwasher safe and bleach resistant RZS685BK10 Oven Mitt, 10" RZS685BK13 Oven Mitt, 13" RZS685BK15 Oven Mitt, 15" RZS685BK17 Oven Mitt, 17" RZS685PMBK17 Puppet-Style Oven Mitt, 17" RZS685PHBK8 Pot Holder/Trivet, 8" x 9" 1 RZS685HHBK6 Handle Holder, 6 ⁄4" Hold everything with the ultimate Oven Mitt in heat protection! Puppet Mitt Pot Holder/Trivet Handle Holder 72 KITCHEN Features breast and thermometer pockets, reversible closures and fold-back cuffs. Long Sleeve Chef Coats • 8 matching pearl buttons • 65% polyester, 35% cotton twill • Features breast and thermometer pockets, reversible closures and fold-back cuffs • White RZEC8SM Small RZEC8M Medium RZEC8LG Large RZEC81X X-Large RZEC82X XX-Large Long Sleeve Chef Coats • 10 matching pearl buttons • 65% polyester, 35% cotton twill Beanies • Black • Unisex, one size fits all RZCOATBKSM Small • 65% polyester, 35% cotton twill RZCOATBKM Medium • Elastic -

New Parking Ordinance Wins Board's Approval

BISDURT EOX Tiirs FLA 32034 Vol. 13, No. 118 BOCA RATON NEWS Sunday, Sept. 1, 1968 18 Pages New parking ordinance wins board's approval Proposal must pass City Council It took Planning and Zoning Board members five months and practically a whole night of debating, but they finally came up with a tighter parking lot ordinance. Now all the proposed ordi- nance needs is the approval of City Councilmen. The ordinance basically lim- its the location of off street parking facilities to the same plot or parcel of land they are intended to serve, with a few exceptions. Exceptions must be okayed by the board following a public hearing. It also places restrictions on the appearance of the parking lot and access routes to the lots. For example the ordinance reads that in no case shall single fam'ly residentially zon- ed property be used for drive- ways for access to the park- ing area. A protective wall also must be provided to hide the parking area from view, and all parking Workmen set aside their hard hats as the city started it's areas must be provided with long-weekend observance of Labor Day. landscaped yards subject to the approval of community appear- m ance board. The whole bit began in March with an appeal by F. L. Brad- City quiet for last Construction is running at double the pace set last year. fute, president of Eoca Atlan- tic Homeowners Association, to stop apartment house construc- 65.. homes in August tors from'building parking lots in tineas family residential i weekend zones. -

Quality Kitchen Products Since 1948 Paring Knives

CATALOG VALID UNTIL JULY 31, 2020 Introducing Anthem Wave details on page 10 PROUDLY Quality Kitchen Products Since 1948 Paring Knives A non-serrated blade Rada’s all-time best seller. Perfectly sized all-around paring knife used for cutting, slicing, and peeling. A) Regular Paring 3¼” blade | 6¾” overall Silver Handle R101 $6.00 Black Handle W201 $6.00 B super fine B) Serrated Regular Paring serration! 3¼” blade | 6¾” overall Silver Handle R142 $6.10 Black Handle W242 $6.10 Paring Gift Sets on Page 30 Super Parer Granny Paring Our largest paring knife provides comfort and versatility. This curved blade is perfect for intricate kitchen tasks. Perfect for paring jobs, big or small. Makes slicing and cutting a cinch – whether in a motion toward or away from you. Super Parer 43⁄8” blade | 83⁄8” overall | Silver Handle R127 $8.10 Granny Paring 23⁄8” blade 57⁄8” overall Black Handle (shown) W227 $8.10 Silver Handle (shown) R100 $6.00 Black Handle W200 $6.00 2 RadaCutlery.com Peeling Paring Heavy Duty Paring This small knife fits nicely in your hand. Exceptional Ideally suited for a wide range of kitchen tasks, this for peeling fruits and vegetables, and great for creating knife offers more control for cooks who prefer a slightly garnishes too. longer handle. Peeling Paring 2½” blade | 61⁄8” overall Heavy Duty Paring 3¼” blade | 71⁄8” overall Silver Handle R102 $6.00 Silver Handle (shown) R103 $6.30 Black Handle (shown) W202 $6.00 Black Handle W203 $6.30 Craftsmanshipsurgical quality T420 high Care Instructions carbon stainless steel blades Hand washing all fine cutlery is finger guard for on all knives recommended to prevent microscopic maximum protection dings on the blades’ cutting edge. -

Fine Art and Collectables Auction Sale Lynden House, Lower Road Trading Estate Ledbury Herefordshire HR8 2SS

Fine Art and Collectables Auction Sale Lynden House, Lower Road Trading Estate Ledbury Herefordshire HR8 2SS Friday 9th October 2020 Sale starts at 10 a.m. Auctioneer: Chris Maulkin FNAEA Buyers Premium 18% Catalogue Price (15%+ VAT) £1.00 Card payments can be accepted by debit card ONLY, there is no charge We are UNABLE to accept credit card payment Sale Room Tel No. 07968 694746 Please note that in line with government guidelines, attendance at the sale will be limited and it will be necessary to pre-register. The sale will be conducted live using the Easylive bidding platform for remote internet bidding. Alternatively, commission bids can be left with the auctioneer. PLEASE NOTE All auction business is governed by the conditions of business, a copy of which are available upon request. 1. Whilst we endeavour to provide accurate descriptions all statements contained in the Catalogue are made without responsibility on the part of the Vendors or the Auctioneers. 2. Lots may carry abbreviations such as a/f (as found, considerable damage), the absence of such a note does not imply that the lot is without defect. 3. The lots will be sold as they stand at the time of the sale with all their qualities and defects - irrespective of their description in the catalogue. 4. Any measurements and weights are approximate. Please note all weights given are in avoirdupois ounces unless stated otherwise. 5. All statements contained in the Catalogue as to the authenticity, attribution, genuineness, origin, authorship, date, age, period, condition or quality of any lot are statements of opinion and are not to be taken as, or as implying, statements or representations of fact. -

Military Despatches Vol 18, Dec 2018

Military Despatches Vol 18 December 2018 What’s the real story Unsolved mysteries of Nazi Germany It’s a tradition Some military Christmas traditions Daralago Sahasa The fearless courage of the Gurkha Nuts! General Anthony McAuliffe Head-to-Head World War II paras For the military enthusiast CONTENTS December 2018 Page 48 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and Battlefield techno-speak that few Pearl Harbour outside the military could hope to under- 26 stand. Some of the terms Features were humorous, some A matter of survival 6 This month we look at finding were clever, while others and gathering plants for food. were downright crude. Unsolved Nazi Mysteries Ten mysteries of Nazi Germany 30 that have never been solved or Remembrance Day Round-up Part of Hipe’s “On the explained. We look at some of the events couch” series, this is an 12 18 that commemorated Armistice interview with one of It’s a traditional thing Christmas and a world at war Day. author Herman Charles How did the British celebrate For anyone in the military, Quiz Bosman’s most famous spending Christmas on duty or Christmas during World War I? characters, Oom Schalk away from home is never great. 21 22 A taxi driver was shot Lourens. Hipe spent time in Yet there are some that at least The Sharp Edge try and make it easier. -

Holiday-2Nd Draft.Indd

HOLIDAY COOKING AND GIFT COLLECTION 2010 FREE SHIPPING see page 46 for details HOLIDAY SHOPPINGS O NG Great Ideas page 2 Holiday Baking page 6 Stocking Stuffers page 8 Entertaining page 10 Gourmet page 23 LOTS OF NEWITEMS Visit us online to view our entire collection of over 1500 products RECIPE CARDS AND BOX New AG1895 Box $ 14.95 Oversized AG1896 Cards $ 4.95 NORDIC WALKING STICKS Because no kitchen is truly complete without a rec- ipe box, this will store your fantastic family food se- AG1834 $ 39.95 crets in a neat and organized manner. The Recipe Get a low impact full body workout with these Nor- Box is made out of strong cardboard and measures dic Walking Sticks. Nordic walking is an effi cient, 6.5” x 4” x 4.5”. The box comes with 24 double- low-stress, exercise technique that makes use of sided starter cards complete with dividers. Recipe walking poles to engage the upper and lower body Box holds as many as 96 cards. If you need more in a workout that has clinically proven physical and cards, however, these double-sided recipe cards, psychological benefi ts. These Nordic Walking Sticks are just what you need. Made specifi cally for the have adjustable poles, 35.5” to 54”, and feature built Recipe Box, cards are made of stronger paper and in springs that offer more cushioning and fl exibility. measure 4” x 6”. Fits standard size recipe boxes as The set includes 2 telescopic walking sticks, 2 inter- well. 24 cards per package. changeable rubber tips, step counter, refl ective safety wrist strap and nylon carrying pouch. -

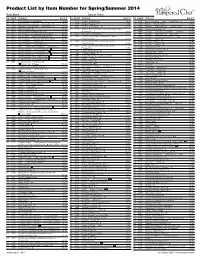

Spring 2014 Product List by Item Number

Product List by Item Number for Spring/Summer 2014 Guest Name Email or Phone Pg. Item# Product price $ Pg. Item# Product price $ Pg. Item# Product price $ 33 1001 Cutting Board — Bar Board 10.50 3 1236 Garden Cultivator l 24.00 55 1691 Mix ‘N Scraper ® — Mini — Cobalt Blue l 10.50 48 1003 Bamboo Cheese Board — Reversible l 27.50 3 1237 Garden Weeder l 15.00 59 1692 Brush — Round Scrub 9.00 31 1005 Bamboo Carving Board — Reversible l 73.50 3 1238 Garden Transplanter l 24.00 55 1694 Scraper — Batter Me Up — Orange Swirl 12.50 33 1012 Cutting Board ★ 18.50 3 1239 Garden Pruning Shears l (Excluding Blades 41 1695 Flour/Sugar Shaker l 7.50 32 1013 Cutting Mat — Flexible (Set of 3) 17.00 & Springs) 29.50 55 1696 Scraper — Stressed is Desserts — Orange 12.50 33 1014 Cutting Board — Large with Juice Wells 35.50 25 1241 Microwave Chip Maker 26.50 55 1697 Scraper — Batter Me Up — Blue Swirl 12.50 32 1015 Cutting Mat — Small Flexible (Set of 3) 10.50 62 1245 On-the-Go Insulated Collapsible Cooler — 55 1698 Scraper — Stressed is Desserts — Pink 12.50 33 1016 Cutting Board — Medium with Juice Wells 21.50 Gray Chevron 36.00 55 1701 Scraper — Mega l 20.50 33 1018 Cutting Board — Cobalt Blue 18.50 62 1246 On-the-Go Insulated Beverage Cooler — 55 1702 Scraper — Micro l 13.50 Gray Chevron 16.50 33 1023 Cutting Board — Large Grooved 33.00 55 1703 Scraper — Master l 16.50 62 1248 On-the-Go Insulated Beverage Cooler — 33 1037 Knife — Color Coated Tomato — Cobalt Blue 15.50 41 1706 Torte Pan Set l 29.00 Paisley Dot 16.50 30 1051 Forged Cutlery — 3.5" Paring -

GETTING TOUGH Brooklyn Women's Martial Arts

No. 17 October 15, 1989 $1.50 GETTING TOUGH Brooklyn Women's Martial Arts COMMON 1H1lIADS: HBO'S DlNMARK'S GAY GROOMS PATCHWORK POLI1'ICS URIAN AIDS ACIIVIS1S DOWNTOWN DOWN AND OUT NEWS • SEXUALPOUTICS' HEALm' 11IE ARTS "S11anghaied!JJ he groaned. "My head-/" c.n ..... c.Rs Chip Duckett presents MARS NEEDSMEN/Sunday Nights at Mars/Dancing / Go-Go Boys / Drag Queens / Live Bands 7 OJ's Michael Connolly, Larry Tee, Perlidia & John Suliga/West Side Highway and 13th Street QPM-4AM Theater (Big Hotel) 48 Theater (Orpheus Descending) 49 lANCE RI~GEL Video (Hungry Hearn) 50 MAKES Video (Lesbian and Gay Video Festival) 52 HISTORY WITH Television (Common Threads) 51 NY STATE I See page:22. Art (The Quilt: ResjXmSe To A National Crisis) 53 Photo: I Books (Manhattan On TheRocks) 54 Peter LeVa;sseur On The Cover: Brooklyn Women's Martial Arts photographed by T.L.Litt In Our Own Hands (McCarthy&Kirschenbaum) I 30 GE1TING TOUGH Kelly Kuwahara:On Brooklyn Women's MartialArts Outspoken (Editorial) 4 Dykes to Watch Out For (Bechdel) 6 Sdomayor 6 Xeroxed 8 Nightmare of the Week 9 Out Of Control (Day) 32 Look Out 40 Out Of My Hands (Ball) 42 Gossip Watch (Signorile) 43 Social Terrorism (Conrad) 44 From Tom Kalin's They are lost to vision altogether Homoscope (deZodiaca) 47 Bar Guide 56 LOOKING KINDA QUEER Community Directory 58 RayNavarro Screens The Queer Filmsand Tapes Of How l}) ILook? 38 Classifieds 61 Personals . 66 Going Out Calendar (X) 78 DANGERS BELOW 14TH STREET Crossword (Greco) 82 John Umlaut Braves the Perils of Downtown 46 Gays and the Mainstream -

Volume 7 Our Dedication to Innovation and Quality

Volume 7 Our Dedication to Innovation and Quality Messermeister is committed to designing new and The innovative products by sourcing the world to find the very best manufacturing quality at the right price for Messermeister the market. We offer a product warranty for the life of the user against defects in materials and workmanship. Messermeister is proud to have served the culinary Story community for 4 decades and will continue into the 1981 next generation. History 1985 The story of Messermeister, “messer” meaning knife and “meister” meaning master, begins with a man and his passion for premium German cutlery. Bernd Dressler was born in Germany and in his teens immigrated with his family to Australia. In 1967 he sought after bigger dreams in America and began his career as a salesperson in cutlery for a large German knife company. By 1995 Bernd’s brother, Bruen, introduced 2000 Messermeister to the Australian market and from In 1981, having gained the necessary sales there the brand began to expand internationally. experience, Bernd decided to start his own Today, proud to be a 100% woman owned venture in cutlery with the help of his wife, Debbie company, Debra, Chelcea and Kirsten Dressler Dressler. Bernd sought to reconnect with his continue Bernd’s mission to bring innovation and countrymen by collaborating with a 3rd generation creativity to the forefront of all kitchens and to knife making family in Solingen, Germany. His provide the highest quality knives and culinary passion for premium cutlery led him to design and tools to culinary students, chefs and home cooks. -

The Cutlery Story

The Cutlery Story A Brief History of the Romance and Manufacture of Cutlery from the Earliest Times to Modern Methods of Manufacture Pocket Knives --- Sportsman's Knives Professional and Industrial Knives and Household Cutlery with a Short Summary on the Selection and Care of Knives and Minimum Requirements of Today's Kitchen by Lewis D. Bement published by THE ASSOCIATED CUTLERY INDUSTRIES OF AMERICA DEERFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS 1950 FOREWORD ~-'/~ Have you ever stopped to consider what life would be like if we had no knives? Even a casual glance at the history of man reveals that the invention and perfection of the knife, which is in effect to say all cutting tools, freed man from endless toil, made possible his thousand and one uses of natural resources, and thereby his evolution from savage to contemporary man. Modern industry, which makes the things with which we work and live, uses knives every hour of the day. The individual workman would be helpless without cutting tools. The housewife, without whom the home would have little meaning, uses a knife on the average of 32 times a day. It is not surprising that cutlery, which we take for granted almost without second thought, is indispensable! ?'UJ#Ie St~Nee ~leWe4 ta 7a&e eeet~ Some 175,000 years ago the un couth, hairy Dawn Man made his knives and axes of stone. For perhaps 15,000 years he developed and improved his crude stone im plements. Then he substituted flint for other coarser stone and employed great skill in chipping, grinding, and polishing this ma terial into knives, axes, spear Stone Flint points, and many other articles that STONE AGE KNIVES made living easier and better. -

Sales of Antiques and Collectors’ Items Wednesday 28 November 2012 09:30

Sales of Antiques and Collectors’ Items Wednesday 28 November 2012 09:30 Penrith Farmers' & Kidd's The Skirsgill Saleroom Agricultural Hall, Skirsgill CA11 0DN Penrith Farmers' & Kidd's ( Sales of Antiques and Collectors’ Items) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 A VICTORIAN BRASS AND GLASS COLUMN OIL LAMP having an etched peach tinted Lot: 7 shade, brass burner with two A LATE 19TH/EARLY 20TH adjusters and mottled glass CENTURY EPNS AND reservoir, raised on a reeded LEATHER BELT with shaped, brass column, stepped circular pierced and impressed links base and turned ceramic base. marked 'EPNS British made'. 47cm(to burner) 59cm(L) Estimate: £140.00 - £180.00 Estimate: £80.00 - £120.00 Lot: 2 A PAIR OF SWAINE & ADENEY Lot: 8 COPPER HUNTING HORNS, A GEORGIAN OAK SPOON one with unmarked white metal RACK with broken swan-neck top mount and mouth piece, the and pierced aperture, two pierced other with mouth piece with racks for twelve spoons, a hinged marks for London, maker D.K. box and base drawer, sold with 16.5cm(h) & 14.5cm(h) twelve 19th century British plate, Estimate: £120.00 - £180.00 fiddle pattern dessert spoons. 73cm(h) Estimate: £150.00 - £200.00 Lot: 3 A SMALL WOODEN PROPELLER, the two shaped Lot: 9 blades with brass boss, marked A 20TH CENTURY CARVED 'A.I.D H43, 8336 T.28153 WOODEN PANEL carved with a 500watt No1', also marked with family of weasels and a bird crows foot under an A. 48cm(L) under ivy. 59cm x 36cm Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 Estimate: £80.00 - £120.00 Lot: 4 A LARGE VICTORIAN COPPER EXTERIOR LANTERN having a Lot: 10 brass finial over the gadrooned A 19TH CENTURY surmount, sloping hexagonal CONTINENTAL CHAMPLEVE superstructure with lion mask ENAMEL MARBLE AND GILT ornaments, the six glazed panels METAL INK STAND having a enclosing the later adapted hinged, circular, finial topped electrical fitting.