Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Augustus Muhlenberg and Phillips Brooks and the Growth of the Episcopal Broad Church Movement

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Parties, Visionaries, Innovations: William Augustus Muhlenberg and Phillips Brooks and the Growth of the Episcopal Broad Church Movement Jay Stanlee Frank Blossom College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Blossom, Jay Stanlee Frank, "Parties, Visionaries, Innovations: William Augustus Muhlenberg and Phillips Brooks and the Growth of the Episcopal Broad Church Movement" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625924. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-x318-0625 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. P a r t ie s , V i s i o n a r i e s , I n n o v a t i o n s William Augustus Muhlenberg and Phillips Brooks and the Growth of the Episcopal Broad Church Movement A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts hy Jay S. F. Blossom 1994 Ap p r o v a l S h e e t This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Jay S. -

GREAT AWAKENING, MAINE, NEW HAMPSHIRE, REVIVAL) LAURA BRODERICK RICARD University of New Hampshire, Durham

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1985 THE EVANGELICAL NEW LIGHT CLERGY OF NORTHERN NEW ENGLAND, 1741-1755: A TYPOLOGY (GREAT AWAKENING, MAINE, NEW HAMPSHIRE, REVIVAL) LAURA BRODERICK RICARD University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation RICARD, LAURA BRODERICK, "THE EVANGELICAL NEW LIGHT CLERGY OF NORTHERN NEW ENGLAND, 1741-1755: A TYPOLOGY (GREAT AWAKENING, MAINE, NEW HAMPSHIRE, REVIVAL)" (1985). Doctoral Dissertations. 1471. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1471 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this rr production. t. P' muscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. -

A Primer on the Government of the Episcopal Church and Its Underlying Theology

A Primer on the government of The Episcopal Church and its underlying theology offered by the Ecclesiology Committee of the House of Bishops Fall 2013 The following is an introduction to how and why The Episcopal Church came to be, beginning in the United States of America, and how it seeks to continue in “the faith once delivered to the saints” (Jude 3). Rooted in the original expansion of the Christian faith, the Church developed a distinctive character in England, and further adapted that way of being Church for a new context in America after the Revolution. The Episcopal Church has long since grown beyond the borders of the United States, with dioceses in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador (Central and Litoral), Haiti, Honduras, Micronesia, Puerto Rico, Taiwan, Venezuela and Curacao, and the Virgin Islands, along with a Convocation of churches in six countries in Europe. In all these places, Episcopalians have adapted for their local contexts the special heritage and mission passed down through the centuries in this particular part of the Body of Christ. “Ecclesiology,” the study of the Church in the light of the self-revelation of God in Jesus Christ, is the Church’s thinking and speaking about itself. It involves reflection upon several sources: New Testament images of the Church (of which there are several dozen); the history of the Church in general and that of particular branches within it; various creeds and confessional formulations; the structure of authority; the witness of saints; and the thoughts of theologians. Our understanding of the Church’s identity and purpose invariably intersects with and influences to a large extent how we speak about God, Christ, the Spirit, and ourselves in God’s work of redemption. -

1966 the Witness, Vol. 51, No. 33

^ WITNESS OCTOBER 20, 1966 10* publication. Editorial and reuse Maybe We're All Heretics for required Articles Permission DFMS. / Should We Build Lavish Churches? A Trialogue Church Episcopal Give Us This Day the of Katherine S. Strong Archives 2020. Chocking the Gospel to Death Martin LeBrecht Copyright NEWS: Big Problems Face the Church Presiding Bishop Tells Council. Faith and Order Meeting in Soviet Union. Churches Pro- test Discontinuing Head Start Funds SERVICES The Witness SERVICES In Leading Churches For Christ and His Church In Leading Churches NEW YORK CITY EDITORIAL BOARD ST. STEPHEN'S CHURCH THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH Tenth Street, above Chestnut OF ST. JOHN THE DIVINE PHILADELPHIA, PENNA. Sunday: Holy Communion 7, 8, 9, 10, JOHN MCGILL KROMM, Chairman W. B. SPOFFOKD SK., Managing Editor The Rev. Alfred W. Price, D.D., Rector Morning Prayer, Holy Communion and The Rev. Gustav C. Meckling, B.D. Sermon. 11; Organ Recital, 3:15 and EDWARD J. MOHR, Editorial Assistant Minister to the Hard of Hearing sermon, 4. O. SYDNEY BABR; LBS A. BELFORD; ROSCOE Sunday: 9 and 11 a.m. 7:30 p.m. Morning Prayer and Holy Communion 7:15 T. Fousrrj RICHARD E. GARY; GORDON C. Weekdays: Mon., Tues., Wed., Thurs., Fri., (and 10 Wed.); Evening Prayer, 3, 12:30 - 12:55 p.m. GRAHAM; DAVID JOHNSON; HAROLD R. LAN- Services of Spiritual Healing, Thurs. 12:30 DON; LESLIE J. A. LANG; BENJAMIN MINIFIE; and 5:30 p.m. THE PARISH OF TRINITY CHURCH WIIXIAM STRINGFELLOW. TRINITY Broadway & Wall St. CHRIST CHURCH CAMBRIDGE, MASS. Rev. Bernard C. Newman, S.T.D., •fr The Rev. -

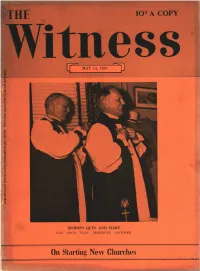

Lo* a COPY on Starting New Churches

THE lO* A COPY Wi t n e 8 s Q MAY 14, 1953 publication. and reuse for required Permission DFMS. / Church Episcopal the of Archives 2020. Copyright BISHOPS QUIN AND HART ONE GOOD TURN DESERVES ANOTHER On Starting New Churches SERVICES The WITNESS SERVICES In Leading Churches In Leading Churches For Christ and His Church THE CATHERDAL OF ST. JOHN CHRIST CHURCH CATHEDRAL THE DIVINE EDITORIAL BOARD Main & Church Sts., Hartford, Conn. New York City ROSCOE T. FOUST, EDITOR; WILLIAM B. Sunday: 8 and 10:10 a.m., Holy Com munion; 9:30, Church School; 11 a.m. Sundays: 7:30, 8, 9 Holy Communion; SPOFFORD, MANAGING EDITOR; ALGER L. Morning Prayer; 8 p.m., Evening Prayer. 9:30, Holy Communion and Address, ADAMS, KENNETH R. FORBES, GORDON C. Weekdays: Holy Communion, Mon. 12 Canon Green; 11, Morning Prayer, GRAHAM, ROBERT HAMPSHIRE, GEORGE H. Holy Communion; 4 Evensong. Ser noon; Tues., Fri. and Sat., 8; Wed., 11; MACMUBRAT JAMES A. MITCHELL, PAUL Thurs., 9; Wed. Noonday Service, 12:15. mons: 11 and 4; Weekdays: 7:30, 8 MOORE JR., JOSEPH H. TITUS. Columnists: (also 8:45, Holy Days and 10 Wed.), CLINTON J. KEW, Religion and the Mind; CHRIST CHURCH Holy Communion. Matins 8:30, Even MASSEY H. SHEPHERD JR., Living Liturgy. Cambridge, Mass. song 5 CChoir except Monday). Open Rev. Gardiner M. Day, Rector daily 7 p.m. to 6 p.m. Rev. Frederic B. Kellogg, Chaplain THE HEAVENLY REST, NEW YORK CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Fredrick C. Grant, Sunday Services: 8, 9, 10 and 11 a.m. Fifth Avenue at 90th Street F. -

In This Issue

A Quaker Weekly VOLUME 2 JUNE 30, 1956 NUMBER 26 IN THIS ISSUE 8PIL fir<t appeMs when the created will turns away from its divine origin, seeks The Problem of Theology its own puny separate good, by Virginia H. Davis and so sheds off the harmon izing light and love, uncover mg the hidden basis of dark ness and fire, pain and wrath. William Penn-Prophet of the Future Thus evil, whether that of the human soul or as shown by Edwin B. Bronner m the destructive, degenera tzve forces of nature, is essen tially a perversion, a disloca tion of harmonized elements. Challenge and Response in the Middle -STEPHEN HOBHOUSE East- Part II by Elmore Jackson Early Religious Freedom in Pennsylvania Quaker Pamphlet Reviews American Indian Policy FlnEEN CENTS A COPY $4.00 A YEAR ' 402 FRIENDS JOURNAL June 30, 1956 Books DOING THE TRUTH, A Summary of Christian Ethics. FRIENDS JOURNAL By JAMES A. PIKE. Doubleday and Company, Inc., New York, 1955. 192 pages. $2.95 In Doing the Truth, James A. Pike takes the reader on a journey of thought and discussion which reveals the depth and clarity of his religious insight. It is a book on the rela tionship of believing and doing. God is the ultimate ground of all being. "Not only is God in and through all things; He is concerned about all things." God means persons to be crea tive, redemptive, and to live and work in community. The Published weekly at 11115 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 2, Pennsylvania (Rittenhouse 6-7669) basis of Christian ethics, therefore, is not a set of laws but the By Friends Publlahlne Corporation individual's response to what God means persons to be. -

Dimensions of Discourse on the Religious Issue During the 1960 Presidential Election

Sentries of Separation: Dimensions of Discourse on the Religious Issue during the 1960 Presidential Election Kevin R McWilliams Thesis Advisor: Professor Alan Brinkley Second Reader: Professor Peter Awn Senior Thesis in History 5 April 2013 McWilliams 1 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………...2 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………........3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter 1………………………………………………………………………………………..10 Chapter 2………………………………………………………………………………………..18 Chapter 3………………………………………………………………………………………..28 Chapter 4………………………………………………………………………………………..39 Chapter 5………………………………………………………………………………………..52 Epilogue…………………………………………………………………………………………58 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………….62 Secondary Sources……………………………………………………………………….62 Primary Sources………………………………………………………………………….65 McWilliams 2 Abstract The presidential election of 1960 brought religious discourse in American politics to an unprecedented level of national consciousness. John F. Kennedy created a sensational moment as a Roman Catholic seeking the highest public office in the United States. Various groups resistant to any Catholic president organized to increase awareness of the separation of church and state. Faced with mounting opposition based on religion, John Kennedy and his campaign team created a group designed to face the challenges surrounding the issue. Dubbed Community Relations, the team handled every aspect of the religious issue for the Kennedy team. Ultimately winning the election, John Kennedy became the -

The Path of the Episcopal Church

The Path of the Episcopal Church Here are chronicled the events and their dates leading up to the "Walking Apart" of the US branch of the Anglican Communion from the main body of both the Communion and the “one, holy, catholic and apostolic church”. The Timeline 1965-1966 Heresy charges brought against Bishop James Pike, who had March 2000 Primates' meeting in Oporto, Portugal, issued pastoral letter declared that "the Church's classical way of stating what is represented by the upholding the authority of Scripture. doctrine of the Trinity is…not essential to the Christian faith"; Bishop Pike was censured, but there was no trial for heresy because the Church believed July 2000 General Convention of ECUSA approved Resolution D039 such a trial would give it an "oppressive image”. acknowledging relationships other than marriage and existence of disagreement on the Church's teaching. 1967 Weakening position on abortion appears to begin with 1967 General Convention Statement on Abortion. March 2001 Primates' meeting in Kanuga, N.C., issued pastoral letter acknowledging estrangement in Church due to changes in theology and 1968 Membership in the Episcopal Church peaks, by 2005 there is a net loss practice regarding human sexuality, and calling Communion to avoid actions of around one million members. that might damage "credibility of mission." 1974 Irregular ordination of women to the priesthood, “The Philadelphia April 2002 Primates' meeting at Canterbury issued a report recognizing the Eleven". responsibility for all bishops to be able to articulate the fundamentals of faith so as to maintain the Church in truth. 1976 General Convention of ECUSA approved Resolutions A068 and B101 calling for study/dialogue on sexuality and ordination of homosexuals. -

John-F-Kennedy-Separ

Separating God and State: The faith of John F. Kennedy James C. Denison, Ph.D. Denison Forum on Truth and Culture www.denisonforum.org Adolf Hitler told the German clergy, "You take care of the church. I'll take care of the German people." At the time, the German population had become accustomed to the doctrine of the "two spheres": Christ is Lord of the church while the Kaiser is lord over the political sphere.1 We know the results of such spiritual bifurcation. A similar trend is at work in American culture today. For instance, a recent poll indicates that 72 percent of Americans, including 67 percent of evangelicals, believe it's permissible to disagree with church teaching on abortion. Separation of church and state has become separation of faith and state. In a nation that leads the industrialized world in teenage pregnancy, with 100,000 child pornography websites, where illegal drugs cost our country $215 billion annually, how is our spiritual bifurcation working for us? John F. Kennedy was the second Catholic candidate for president in American history. Facing vociferous opposition from Protestants amid allegations that he would be unduly influenced by the Vatican, Kennedy repeatedly stated: "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President, who happens also to be a Catholic." Kennedy continued to claim that religion is personal while politics are public. This segregation allayed the fears of the voting public and constitutes his lasting effect on religion in America. Has this effect been positive or negative? How does it relate to faith and culture today? The faith of John F. -

Take a Look at This

Free Community Newspaper Helping Build Our Community May 2020 First Edition OUR FIRST ISSUE TAKE A LOOK IN THIS ISSUE You’ll find stories about our Pike Township Fire Department’s 1st Responders, Paramedics, and AT THIS other Healthcare Champions. Photography by Mid-States Media Group Photograph courtesy of Pike Fire Department FEATURE STORY FEATURE STORY Read Fire Chief Trag’s story about the most challenging call Dr. James Pike and his Urgent Care Center is saving lives and Pike Township Fire Department has ever taken and how they teaching us how to live through the COVID-19 challenges. responded. See pages 4-5. See pages 6-7. Meet the Paper The founders of the Pike Pulse all are in agreement. They see value in Pike’s community — and they want to bring it closer together, especially after a time when we’ve been required to be apart. Pike Pulse Publisher, Clint Fultz, who is treasurer of the Pike Township Our mission is to help build a Resident’s Association and a member of the Pike Township Advisory Commit- stronger sense of community by tee for the Westside Chamber of Commerce, is the driving force behind the paper’s launch. Having lived in Pike Township for almost 40 years, he’s long keeping our fingers on the pulse seen the need for a community newspaper, something he says he of Pike Township and publishing hopes will “really help stitch the community together.” positive, upbeat, and relevant news. A successful businessman and owner of commercial real es- tate, Fultz is a CCIM who has brokered land for public schools, local Pike Pulse is the only free businesses, and several locations for national companies in Pike. -

Scout and Ranger Personal

Narratives ofthe Trans-Mississippi Frontier SCOUT AND RANGER BEING THE PERSONAL ADVENTURES OF JAMES PIKE of the Texas Rangers in 1859-60 Reprinted from the edition of I 865, with Introduction and Notes by Carl L. Cannon PRINCETON ·· PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS ·• 1932 PRINTED AT THE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY, U.S.A. London: Humphrey Milford Oxford Uniuersity Press SCOUT AND RANGER ··'"" .. :_ .. :j-·~ ~~.. _:, ,,.( /~\?~i _;:-.... RANGER PIKE COPYRIGHT, 1932, PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS NARRATIVES OF THE TRANS-MISSISSIPPI FRONTIER CARLL. CANNON, General Editor ROUTE ACROSS THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS By OVERTON JOHNSON and WM. H. WINTER EDITED BY CAlU. L. CANNON A JOURNAL OF THE SANTA FE EXPEDITION UNDER COLONEL DONIPHAN By JACOB S. ROBINSON EDITED BY CARLL. CANNON THE EMIGRANTS' GUIDE TO CALIFORNIA By JOSEPH E. w ARE EDITED BY JOHN CAUGHEY THE PAST AND PRESENT OF THE PIKE'S PEAK GOLD REGIONS By HENRY VILLARD EDITED BY I.E ROY R.. · HAFEN HALL J. KELLEY ON OREGON A collection of five of Kelley's published works and a number of hitherto unpublished letters EDITED BY F. W. POWELL SCENERY OF TH1E PLAINS, MOUNTAINS AND MINES By FRANKLIN LANGWORTHY EDITED BY PA UL C. PHILLIPS THE EMIGRANTS' GUIDE TO OREGON AND CALIFORNIA By LANSFORD w. HASTINGS A facsimile of the edition of 1845, with Introduction and Notes by Charles H. Carey SCOUT AND RANGER By CORPORAL ]AMES PIKE EDITED BY CARL L. CANNON PRINTED AT THE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY, U.S.A. ADDENDUM After this edition of Scout and Ranger had gone to press, the following additional facts came to light : Pike's f a11iily history as given by his grand niece, Grace F. -

Eisenhower, Dwight D.: Papers, Post-Presidential, 1961-69

EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: PAPERS, POST-PRESIDENTIAL, 1961-69 SECRETARY’S SERIES (A67-37, A68-1, A68-14) Processed by: JWL Date Completed: February 1994 Scope and Content Note The Secretary’s Series consists of two subseries, a subject subseries which covers essentially the years 1964-1965, and a correspondence, or reading, subseries comprised of carbon copies of outgoing correspondence of General Eisenhower. This second subseries is organized in the following annual segments: 1962, 1963, 1964-65, 1966 and 1967. Although the files plan, or set of criteria by which materials were selected for Secretary’s Series was not found, the file may have been created in order to have readily at hand certain important materials frequently needed by General Eisenhower and/or his office staff. The Subject Subseries is organized in a fashion similar to the organization of the subject segments of the annual Principal Files, that is, particular subjects bear code designations- example, “AP” for appointments, “IN” for invitations, “ME” for messages, and so forth. A sample comparison of documents from the Subject Subseries with those found in the equivalent subject files in the Principal Files revealed that duplicate copies were often found in both files. Large segments, however, appear to be unique to this file and a substantial portion of this documentation is historically significant. For example, the “Politics” (PL) files found in Boxes 2 through 5 contain important original materials, most of it bearing on the 1964 elections. Likewise, the Speech and Publications files contain important unique documentation of Eisenhower’s literary activities. Such other subjects as “FO” (Foreign Affairs) and “FE” (Federal Government) are also apparently unique to this file.