Temple of Heaven, Beijing, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beijing - Hotels

Beijing - Hotels Dong Fang Special Price: From USD 43* 11 Wan Ming Xuanwu District, Beijing Dong Jiao Min Xiang Special Price: From USD 56* 23 A Dongjiaominxiang, Beijing Redwall Special Price: From USD 66* 13 Shatan North Street, Beijing Guangxi Plaza Special Price: From USD 70* 26 Hua Wei Li, Chaoyang Qu, Beijing Hwa (Apartment) Special Price: From USD 73* 130 Xidan North Street, Xicheng District Beijing North Garden Special Price: From USD 83* 218-1 Wangfujing Street, Beijing Wangfujing Grand (Deluxe) Special Price: From USD 99* 57 Wangfujing Avenue, International Special Price: From USD 107* 9 Jian Guomennei Ave Dong Cheng, Beijing Prime Special Price: From USD 115* 2 Wangfujing Avenue, Beijing *Book online at www.octopustravel.com.sg/scb or call OctopusTravel at the local number stated in the website. Please quote “Standard Chartered Promotion.” Offer is valid from 1 Nov 2008 to 31 Jan 2009. Offer applies to standard rooms. Prices are approximate USD equivalent of local rates, inclusive of taxes. Offers are subject to price fluctuations, surcharges and blackout dates may apply. Other Terms and Conditions apply. Beijing – Hotels Jianguo Special Price: From USD 116* * Book online at www.octopustravel.com.sg/scb or call Octopus Travel at the local number stated in the website. Please quote “Standard Chartered Promotion.” Offer applies to standard rooms. Prices are approximate USD equivalent of local rates, inclusive of taxes. Offers are subject to price fluctuations, surcharges and blackout dates may apply. Other Terms and Conditions apply. 5 Jianguo Men Wai Da Jie, Beijing Novotel Peace Beijing • Special Price: From USD 69 (10% off Best unrestricted rate)* • Complimentary upgrade to next room category • Welcome Drink for 2 • Late checkout at 4pm, subject to availability • Complimentary accommodation and breakfast for 1 or 2 children *Best unrestricted rate refers to the best publicly available unrestricted rate at a hotel as at the time of booking. -

Temple of Heaven Cultural Circle to Emerge

CHINA DAILY SPECIALSUPPLEMENT FRIDAY MARCH 9, 2007 19 Temple of Heaven cultural circle to emerge Balancing the protection of cultural HIGHLIGHT OF cultural relics protection area Qinian Multi-Cultural Street, sports competitions, the sale were relocated, experts were which lies to the east of the of sports equipment as well relics with better living conditions LOCAL GOVERNMENT WORK REPORT 2007 able to meticulously inspect Front Gate cultural innova- as sports-related leisure and the historical heritage sites and tion industrial area, will see entertainment activities. The government of Chon- sured Watchtower over the Front CHONGWEN DISTRICT, BEIJING set down individual protection the construction of a series The goal of the park is to form gwen District in Beijing is Gate, the Yongding Gate Tower, programs. of modern buildings such as a sports leisure and entertain- committed to building the and the Zuoan Gate Tower, situ- This practice strikes a bal- luxury hotels, an international ment center, as well as a sports Cultural Circle of the Temple ated to the northeast, northwest, on constructing three areas residents have been moved out ance between protection of auction center and a cultural business exchange center. A of Heaven, in order to develop southwest and southeast corners with distinct industrial func- of the area, while numerous cultural relics and improve- innovation industrial base for sports sector headquarter base the economy while preserv- respectively of the district, form tions – the Front Gate cultural hazardous structures have ment of living conditions, and youngsters. In the southern and a sports R&D (research and ing local characteristics, as a square city pattern. -

Beijing City Day Tour to Forbidden City and Temple of Heaven

www.lilysunchinatours.com Beijing City Day Tour to Forbidden City and Temple of Heaven Basics Tour Code: LCT - BJ - 1D - 04 Duration: 1 Day Attractions: Forbidden City, Temple of Heaven, Summer Palace, Tian’anmen Square Overview: Embark on a journey to four major classic attractions in Beijing in a single day. Take the morning to explore the palatial and extravagant Forbidden City and the biggest city square in the world - Tian’anmen Square. In the afternoon, head for the old royal garden of Summer Palace and Temple of Heaven, the very place where emperors from Ming and Qing Dynasties held grand sacrifice ceremonies to the heaven. Highlights Stroll on the Tian’anmen Square and listen to the stories behind all the monuments, gates, museums and halls. Marvel at the exquisite Forbidden City - the largest palace complex in the world. Enjoy a peaceful time in Summer Palace. Meet a lot of Beijing local people in Temple of Heaven; Satisfy your tongue with a meal full of Beijing delicacies. Itinerary Date Starting Time Destination Day 1 09:00 a.m Forbidden City, Temple of Heaven, Summer Palace, Tian’anmen Square After breakfast, your tour expert and guide will take you to the first destination of the day - Tel: +86 18629295068 1 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] www.lilysunchinatours.com Tian’anmen Square. Seated in the center of Beijing, the square is well-known to be the largest city square in the world. The fact is the Tian’anmen Square is also a witness of numerous historical events and changes. At present, the square has become a place hosting a lot of monuments, museums, halls and the grand celebrations and military parades. -

Guidelines for Authors

The Axis of Ancient BeiJing that Declaraed the World Cultural Heritage and the Tourism of BeiJing First Author Beijing University of Technology, the Collage of Architecture and Urban Planning, Zhangfan, No.100 Pingleyuan, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This essay is mainly about six aspects on the Axis of Ancient BeiJing which Declaraed the WCH and it’s relationship between the Tourism of BeiJing: First, how to find out the Outstanding Universal Value of the Axis? Second, how to estimate the OUV? Which Criterias shall we choose for the assessment? Third, Authenticity vs Integrality: Rebuilt or Restoration (Rehabilitation)? Some discussions about the rebuilt of QianMen (the front gate which is also the south gate of the inner city) District and the DiAnMen (the north gate of the inner city). Forth, what are the main tourism problems along the Axis of Ancient BeiJing and what we are going to do with it after the Axis’ Declaration? Keywords: The Axis of Ancient BeiJing, WCH (World Cultural Heritage), OUV (Outstanding Universal Value), Criteria for the Assessment of OUV, Tourism (three lines) Introduction (two lines) The ancient capital of Beijing's central axis which is the landmark of the city center, is also the world's longest existing city axis. There are many existing heritage buildings along the 7.8 km of the axis including the Yongding Gate (rehabilitation), Yan Tun, Temple of Heaven, Xian Nong Temple, Zhengyang Gate, the Imperial Ancestral Temple, Tiananmen Square, Forbidden City, Jingshan, Beihai, Pudu Temple, Wanning Bridge, fire temples, the Drum Tower, Bell Tower and so on(Figure 1: Heritage Area and it’s buffer zone). -

Remodeling and Reflection of Historic District - Taking Qianmen Street As an Example

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 112 4th International Conference on Renewable Energy and Environmental Technology (ICREET 2016) Remodeling and Reflection of Historic District - Taking Qianmen Street as an example WANG ZHI 1, a, 1 Institution of Agricultural Scientech Information,Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing, 100097 aemail: [email protected] Keywords: Historic District, Qianmen Street, Business evolution, Remodeling. Abstract. Qianmen area is no longer in those years of prosperity spectacular, there is a historical reason, a more important reason is its commercial positioning fuzzy, overall positioning error caused. This paper studies the Qianmen Street commercial development context, to extract the elements of Qianmen Street economy and cultural prosperity. We would like to see through the nature of the phenomenon and find Qianmen Street "soul", which stimulate the revival of the potential for the revival of the historic district of cultural, economic revival and morphological remodeling, providing development ideas and implementation strategies. Introduction Qianmen Street was founded 570 years ago, it is the only way forroyal ritual, hunting, patrol at Ming and Qing Dynasties, known as "Heaven Street". Sedimentary nearly 600 years, making Beijing Qianmen Street became the architectural culture, business culture, cultural hall, opera culture, folk culture precipitate profound characteristic historic district, is one of Beijing landmark. Today, however, Qianmen Street no longer have the same spectacular, so many people confused by its development. History Commercial Streets become ordinary street shops, tasteless attractions. By combing historical context of Qianmen Street, the author were compared for business forms and characteristics in different periods, to extract the Qianmen Street’s economic and cultural boom operating mode. -

Beijing Subway Map

Beijing Subway Map Ming Tombs North Changping Line Changping Xishankou 十三陵景区 昌平西山口 Changping Beishaowa 昌平 北邵洼 Changping Dongguan 昌平东关 Nanshao南邵 Daoxianghulu Yongfeng Shahe University Park Line 5 稻香湖路 永丰 沙河高教园 Bei'anhe Tiantongyuan North Nanfaxin Shimen Shunyi Line 16 北安河 Tundian Shahe沙河 天通苑北 南法信 石门 顺义 Wenyanglu Yongfeng South Fengbo 温阳路 屯佃 俸伯 Line 15 永丰南 Gonghuacheng Line 8 巩华城 Houshayu后沙峪 Xibeiwang西北旺 Yuzhilu Pingxifu Tiantongyuan 育知路 平西府 天通苑 Zhuxinzhuang Hualikan花梨坎 马连洼 朱辛庄 Malianwa Huilongguan Dongdajie Tiantongyuan South Life Science Park 回龙观东大街 China International Exhibition Center Huilongguan 天通苑南 Nongda'nanlu农大南路 生命科学园 Longze Line 13 Line 14 国展 龙泽 回龙观 Lishuiqiao Sunhe Huoying霍营 立水桥 Shan’gezhuang Terminal 2 Terminal 3 Xi’erqi西二旗 善各庄 孙河 T2航站楼 T3航站楼 Anheqiao North Line 4 Yuxin育新 Lishuiqiao South 安河桥北 Qinghe 立水桥南 Maquanying Beigongmen Yuanmingyuan Park Beiyuan Xiyuan 清河 Xixiaokou西小口 Beiyuanlu North 马泉营 北宫门 西苑 圆明园 South Gate of 北苑 Laiguangying来广营 Zhiwuyuan Shangdi Yongtaizhuang永泰庄 Forest Park 北苑路北 Cuigezhuang 植物园 上地 Lincuiqiao林萃桥 森林公园南门 Datunlu East Xiangshan East Gate of Peking University Qinghuadongluxikou Wangjing West Donghuqu东湖渠 崔各庄 香山 北京大学东门 清华东路西口 Anlilu安立路 大屯路东 Chapeng 望京西 Wan’an 茶棚 Western Suburban Line 万安 Zhongguancun Wudaokou Liudaokou Beishatan Olympic Green Guanzhuang Wangjing Wangjing East 中关村 五道口 六道口 北沙滩 奥林匹克公园 关庄 望京 望京东 Yiheyuanximen Line 15 Huixinxijie Beikou Olympic Sports Center 惠新西街北口 Futong阜通 颐和园西门 Haidian Huangzhuang Zhichunlu 奥体中心 Huixinxijie Nankou Shaoyaoju 海淀黄庄 知春路 惠新西街南口 芍药居 Beitucheng Wangjing South望京南 北土城 -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Beijing Travel Guide

BEIJING TRAVEL GUIDE FIREFLIES TRAVEL GUIDES BEIJING Beijing is a great city, famous Tiananmen Square is big enough to hold one million people, while the historic Forbidden City is home to thousands of imperial rooms and Beijing is still growing. The capital has witnessed the emergence of more and higher rising towers, new restaurants and see-and-be-seen nightclubs. But at the same time, the city has managed to retain its very individual charm. The small tea houses in the backyards, the traditional fabric shops, the old temples and the noisy street restaurants make this city special. DESTINATION: BEIJING 1 BEIJING TRAVEL GUIDE The Beijing Capital International Airport is located ESSENTIAL INFORMATION around 27 kilometers north of Beijing´s city centre. At present, the airport consists of three terminals. The cheapest way to into town is to take CAAC´s comfortable airport shuttle bus. The ride takes between 40-90 minutes, depending on traffic and origin/destination. The shuttles leave the airport from outside gates 11-13 in the arrival level of Terminal 2. Buses depart every 15-30 minutes. There is also an airport express train called ABC or Airport to Beijing City. The airport express covers the 27.3 km distance between the airport and the city in 18 minutes, connecting Terminals 2 and 3, POST to Sanyuanxiao station in Line 10 and Dongzhimen station in Line 2. Jianguomen Post Office Shunyi, Beijing 50 Guanghua Road Chaoyang, Beijing +86 10 96158 +86 10 6512 8120 www.bcia.com.cn Open Monday to Saturday, 8 am to 6.30 pm PUBLIC TRANSPORT PHARMACY The subway is the best way to move around the Shidai Golden Elephant Pharmacy city and avoid traffic jams in Beijing. -

EBNX (Tuesday.)】

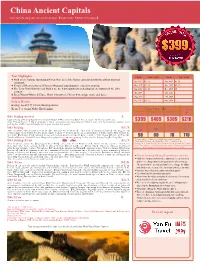

China Ancient Capitals Itinerary:Beijing Arr.-Xi’an-Xi’an Dep.【Tour Code: EBNX (Tuesday.)】 Tour Highlights: Month Tues. Arrival Month Tues. Arrival ● Walk on the famous Juyongguan Great Wall to feel the history associated with this almost mystical landmark. Apr. 2019 09, 16 Oct. 2019 08, 22 ● Temple of Heaven,Ancient Chinese Ming and qing dynasties emperors, praying. May. 2019 07, 21 Nov. 2019 05, 19 ● The Terra Cotta Warriors and Horses are the most significant archeological excavations of the 20th Jun. 2019 11, 18 Dec. 2019 10 century. Jul. 2019 - Jan. 2020 - ● Tang Dynasty Music & Dance Show is known as China's first antique music and dance. Aug. 2019 - Feb. 2020 - Deluxe Hotels: Sep. 2019 03, 17 Mar. 2020 - Beijing: Local 5 ☆ U Hotel Beijing/similar Xi’an: 5 ☆ Grand Noble Hotel/similar Tour Fare($) Single Room Supp. Child between 2-11 Child between 2-11 ($) Adults years old with bed years old without bed D01 Beijing Arrival X Upon arriving at Beijing Capital International Airport (PEK), transfer to hotel. Free at leisure for the rest of the day. (Free Pick-up Period: 9:00a.m.-midnight 1:30a.m.; passengers arriving adjacent within 2 hours will be picked up together; extra $399 $409 $309 $210 pick up fee: USD60 vehicle/transfer for 2-3pax, exclude tour guide). Admission fee as Extra pick-up/ Early check in/ Service Charge indicated drop-off Extend stay D02 Beijing B/L/X (USD) ( ) (USD) (USD) After breakfast, take an outside view of 【the National Grand Theater】. Then visit 【Tiananmen Square】-the biggest city USD central square in the world, the area of the square is about 44 hectares and it can accommodate 1 million people. -

October 10 to 21, 2019

Join SPIRAL International’s Paths of Chinese Spirituality Tour October 10 to 21, 2019 DISCOVER THE DIFFERENT FACES OF CHINESE SPIRITUALITY! Explore four of China’s most fascinating cities! World-famous historical sites Awe-inspiring places of worship Authentic local dishes Beijing: China’s capital for more than 800 years. Discover the Forbidden City, Tiananmen Square, the Temple of Heaven, the Summer Palace and the unforgettable Great Wall. Observe a Baiyun Daoist ceremony and tour the Chengdu: famous for its adorable baby pandas. Cathedral of Beijing. Discover the Giant Panda Center. Traditional meal: Beijing Roast Duck. Tour the Wuhou Temple. Traditional meal: Chen Mapu Tufu Xi’an: home of the incredible Terracotta Soldiers. Spend an entire morning with the Terracotta Solders; Chongqing: considered the world’s largest visit the unique bathing pool of the Tang Dynasty municipality with a population of 35 million. royal family and the Museum of Chinese Folk Culture. Explore the Huaqing Buddhist Temple and the Visit the Huajuexiang Mosque. Taoist Lingbao Pagoda. Traditional meal: Chinese dumplings Traditional meal: Chongqing Hot Pot. Cost of the 12-day trip: $3,800 (includes air fare!) Includes round-trip international airfare to Beijing, hotel, all meals, all transportation within China, entertainment, international travel insurance, and the visa application fee. Personal expenses are not included. Minimum group size is 15. The group will be led by Laurie Gossens, retired Vermont School Superintendent and experienced world traveler. How to participate Today! Send a deposit of $100 + your registration form to secure your place in the group. The deposit is refundable any time up to July 15. -

Exporting the Silicon Valley to China

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 2020, 10(3), e202016 e-ISSN: 1986-3497 Exporting the Silicon Valley to China Gianluigi Negro 1* 0000-0003-2485-6797 Jing Wu 2 0000-0002-3177-1815 1 University of Siena, ITALY 2 Peking University, CHINA * Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Negro, G., & Wu, J. (2020). Exporting the Silicon Valley to China. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 10(3), e202016. https://doi.org/10.29333/ojcmt/7996 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 7 Feb 2020 This article focuses on the history of Zhongguancun as one of the most important area used by Accepted: 9 Apr 2020 the official Chinese narrative to promote the historical shift from the “made in China” model to the “created in China” one. We reconfigure this process through three historical phases that reflect the engagement of policymakers, business and high-tech agents in the creation of a specific social imaginary. Based on a textual analysis as well as on political and sectorial sources, this historical study argues that Zhongguancun carries a set of cultural values influenced by the Silicon Valley experience, however it still fails to achieve success in terms of creation and innovation. In detail, our article highlights three findings: Zhongguacun satisfied the conditions of creative area only during its first stage, when local industries had to adapt its services and products to the Chinese language and culture. Second, Zhongguancun shared with the Silicon Valley neoliberalists issues such as those related to the risk of a real estate bubble burst. Third, although Chinese documents show that Zhongguancun has not the same creativity outputs compared to the Silcon Valley, it shares with California its financial dynamics mainly driven by huge investments in innovation places like innovation cafes. -

Can China Go High-Tech When Exports Slump? Yu Zhou Vassar College

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 China Beat Archive 3-12-2009 Can China Go High-Tech When Exports Slump? Yu Zhou Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Zhou, Yu, "Can China Go High-Tech When Exports Slump?" (2009). The China Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012. 501. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive/501 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the China Beat Archive at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Can China Go High-Tech When Exports Slump? March 12, 2009 in In Case You Missed It by The China Beat | 3 comments By Yu Zhou As the financial Tsunami batter China’s exporting hubs, everyone is wondering how well China can weather the storm in the next couple of years, but a more important question is how China’s economy will emerge after the crisis. As a result of extensive research, I argue that there have been sustained forces pushing China’s industry to more innovative fields with a stronger orientation to the domestic market. The crisis will only strengthen the shift in a more dramatic manner. This conclusion is based on my research in Beijing’s Zhongguancun, a region dedicated to innovative industry and domestic market.