Lucky Luke Shaped by Myth and History [1] by Annick Pellegrin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'organigramme Des Éditions Dupuis

Journal de bord d'u’une stagiaire Delsy Gérard 1 Profil de l’entreprise Table des matières 3 Dupuis, éditeur de caractères 3 Son combat 3 L’univers 3 La cible primaire 4 Les valeurs 4 Les 6 secteurs du groupe Dupuis 4 Ses atouts 4 Les preuves 5 Histoire du groupe 5 L’organigramme des éditions Dupuis 8 Une petite histoire 9 Quelques exemples de travaux réalisés 12 Buck Danny 12 Quelques pages de présentation des séries du Méga Spirou. 15 Séparation pour le nouvel album de Nelson 21 Simulation de box pour L'Agent 212 et Les Femmes en Blanc 24 3 Profil de l’entreprise Nom : Éditions Prénom : Dupuis Lieu de naissance : Marcinelle Nationalité : Belge Signature : Lieu de résidence : 52, rue Destrée - 6001 Marcinelle Dupuis, éditeur de caractères Son combat Être l’éditeur de référence sur le marché de la bande dessinée. L’uni v er s Depuis sa création en 1938, Dupuis a écrit une grande page de l’Histoire de la bande dessinée. Au-delà de son an- crage franco-belge et des grandes séries qui ont fait sa réputation, la force de l’entreprise repose sur sa capacité à se projeter en avant et à savoir régulièrement réinventer son métier : le lancement des albums cartonnés, l’intégration des studios d’animations ainsi qu’une forte culture marketing et commerciale ont marqué l’histoire du secteur. Dans le même esprit, Dupuis a toujours intégré les métiers de l’édition, de l’animation et des droits dérivés, en vue d’assurer une exploitation cohérente de ses univers. -

Liste Des Bandes Dessinées Jeunes Version 26/02/2018 Page 1 Disponible Disponible Temporairement Indisponible / À Paraître Commandé

Disponible Disponible temporairement Indisponible / À paraître Commandé #5 Le tour de Gaule d’Astérix Liste des #6 Astérix et Cléopâtre bandes dessinées jeunes #7 Le combat des chefs #8 Astérix chez les Bretons AGENT JEAN (L’) #9 Astérix et les Normands BD AAL #10 Astérix légionnaire #11 Le bouclier Averne Saison 1 #12 Astérix aux Jeux Olympiques #1 Le cerveau de l’apocalypse #13 Astérix et le chaudron #2 La formule V #14 Astérix en Hispanie #3 Opération Moignons #15 La Zizanie #4 La prophétie des quatre #16 Astérix chez les Helvètes #5 Le frigo temporel #17 Le domaine des Dieux #6 Un mouton dans la tête (2014) #18 Les lauriers de César #7 L’ultime symbole absolu (2014) #19 Le devin #8 Le castor à jamais (2015) #20 Astérix en Corse H.S Les dossiers secrets de moignons (2015) #21 Le cadeau de César #22 La grande traversée Saison 2 #23 Obélix et compagnie #1 Épopée virtuelle (2016) #24 Astérix chez les Belges #2 La nanodimension (2017) #25 Le grand fossé #3 (9 avril 2018) #26 L’odyssée d’Astérix #27 Le fils d’Astérix AMULET #28 Astérix chez Rahàzade BD KIB #29 La rose et le glaive #30 La galère d’Obélix #1 Le gardien de la pierre (2008) #31 Astérix et Latraviata #2 La malédiction du gardien de la pierre (2009) #32 Astérix et la rentrée gauloise #3 Les chercheurs de nuages (2010) #33 Le ciel lui tombe sur la tête #4 Le dernier conseil (2011) #34 L’anniversaire « Le livre d’or » #5 Le prince des elfes (2012) #35 Astérix chez les Pictes #6 L’évasion (2016) #36 Le papyrus du César #7 Feu et lumière (2016) #37 Astérix et la transitalique (2017) -

Subversion of the Western Myth, the Western in Modern Literature a Case Study of Patrick Dewitt’S the Sisters Brothers and Cormac Mccarthy’S Blood Meridian

Subversion of the Western Myth, the Western in Modern Literature A Case Study of Patrick deWitt’s The Sisters Brothers and Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian Word count: 27.798 Sebastiaan Mattheeuws Student number: 01405193 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Marco Caracciolo A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Linguistics and Literature: Dutch-English. Academic year: 2017 – 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the year I found myself lucky that there were many people who were there to support and help me in the long creation process that was this dissertation. A special word of thanks is the least I can give. First of all I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Dr. Marco Caracciolo, for being the supervisor every student dreams of having, for giving me advice whenever I felt I needed it, for stimulating me to come up with my own ideas and for being enthusiastic yet critical when I presented them. Secondly, Prof. Dr. Hilde Staels who has introduced met to The Sisters Brothers in her lecture on contemporary Canadian literature and provided me with a list of initial sources on the Western. Saar for motivating me during the many hours we spend working side by side each on our own dissertations. My parents and my brothers for putting up with my absence and for giving me the support I needed. (Sorry that I somewhat ruined our vacation in The Netherlands by locking myself in my room for approximately half of the time). My other friends, you all know who you are, for supporting me in this process and giving me the opportunity to relax and do something else once in a while. -

Oklahoma Territory Inventory

Shirley Papers 180 Research Materials, General Reference, Oklahoma Territory Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials General Reference Oklahoma Territory 251 1 West of Hell’s Fringe 2 Oklahoma 3 Foreword 4 Bugles and Carbines 5 The Crack of a Gun – A Great State is Born 6-8 Crack of a Gun 252 1-2 Crack of a Gun 3 Provisional Government, Guthrie 4 Hell’s Fringe 5 “Sooners” and “Soonerism” – A Bloody Land 6 US Marshals in Oklahoma (1889-1892) 7 Deputies under Colonel William C. Jones and Richard L. walker, US marshals for judicial district of Kansas at Wichita (1889-1890) 8 Payne, Ransom (deputy marshal) 9 Federal marshal activity (Lurty Administration: May 1890 – August 1890) 10 Grimes, William C. (US Marshal, OT – August 1890-May 1893) 11 Federal marshal activity (Grimes Administration: August 1890 – May 1893) 253 1 Cleaver, Harvey Milton (deputy US marshal) 2 Thornton, George E. (deputy US marshal) 3 Speed, Horace (US attorney, Oklahoma Territory) 4 Green, Judge Edward B. 5 Administration of Governor George W. Steele (1890-1891) 6 Martin, Robert (first secretary of OT) 7 Administration of Governor Abraham J. Seay (1892-1893) 8 Burford, Judge John H. 9 Oklahoma Territorial Militia (organized in 1890) 10 Judicial history of Oklahoma Territory (1890-1907) 11 Politics in Oklahoma Territory (1890-1907) 12 Guthrie 13 Logan County, Oklahoma Territory 254 1 Logan County criminal cases 2 Dyer, Colonel D.B. (first mayor of Guthrie) 3 Settlement of Guthrie and provisional government 1889 4 Land and lot contests 5 City government (after -

Scientifiction, Blake Et Mortimer Au Musée Des Arts Et Métiers 5 Une Rétrospective Inédite Du Chef-D’Œuvre Dessiné D’Edgar P

sommaire Introduction 3 Le mot des commissaires, Thierry Bellefroid et Éric Dubois Notre institution 21 Biographies des commissaires Le Conservatoire national des arts et métiers (Cnam) Le musée des Arts et Métiers Scientifiction, Blake et Mortimer au musée des Arts et Métiers 5 Une rétrospective inédite du chef-d’œuvre dessiné d’Edgar P. Jacobs Partenaires de l’exposition 22 Fondation Roi Baudouin Éditions Blake et Mortimer Parcours de l’exposition 6 Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles La salle Jacobs Les Utopiales Les quatre éléments Thalys Feu Canal BD 2 Terre Air Eau Informations pratiques 24 Le laboratoire Visuels pour la presse 25 Autour de l’exposition 17 Visites guidées Enfants et familles Scolaires Conférences Centre de documentation Catalogue de l’exposition Relations avec les médias Le Dernier Pharaon Musée des Arts et Métiers Amélie Zanetti 01 53 01 82 77 · 06 33 59 34 18 [email protected] LE MOT introduction DES COMMISSAIRES Le pari est de taille : exposer l’un des pères fondateurs de la bande Un Opéra de papier, titre de l’autobiographie d’Edgar P. Jacobs, nous dessinée franco-belge, Edgar P. Jacobs, dont les originaux sont restés guide. Blake et Mortimer c’est du spectacle, avec son et lumière s’il loin des regards depuis sa disparition, en 1987. Ses personnages, Blake vous plait, des acteurs grandioses, des costumes superbes, des décors et Mortimer, n’ont pourtant jamais été si populaires. Mais comment majestueux, des tirades mémorables, le tout au service de thèmes l’exposer ? Pas question d’un accrochage d’hommage, alignant les éternels. Le baryton du 9e art n’abandonne jamais l’opéra. -

The Testament of William S. © Editions Blake & Mortimer / Studio Jacobs (Dargaud-Lombard S.A.) - Sente & Juillard NEW TITLES to DECEMBER 2016 JULY OCTOBER

CATALOGUE 21 SUMMER/AUTUMN 2016 The Testament of William S. © Editions Blake & Mortimer / Studio Jacobs (Dargaud-Lombard s.a.) - Sente & Juillard NEW TITLES TO DECEMBER 2016 JULY OCTOBER P4 P5 P6 P7 P8 P17 P18 P19 P20 AUGUST NOVEMBER P9 P10 P11 P12 P21 P22 P23 P24 SEPTEMBER DECEMBER P13 P14 P15 P16 P25 P26 Dear readers, welcome to Cinebook’s Hunting will be the order of the day for ty, although their days as official agents Spirou is forced to investigate his friend 21st catalogue. some. The Marquis of Anaon is after a par- of Earth are now gone; two volumes of Fantasio, who appears to have turned art This year is the 400th anniversary of ticularly brutal creature that’s been terror- freelancing time travel adventures for your thief. Meanwhile, Lucky Luke is up to his William Shakespeare’s death, and amid ising the French Alps, and has the locals pleasure! And speaking of time travel, our usual shenanigans, supervising the Dal- the other celebrations, Sente and Juillard talking of demons. On the other hand, the latest Espresso Collection title, Clear Blue tons’ on a vengeance spree, helping a have done us the great pleasure of creat- stranded heroes of Barracuda find them- Tomorrows, explores a man’s attempt to newly founded town survive, and dealing ing a new adventure of Blake & Mortimer selves on an island populated by dan- change his past – and his memories of the with a haunted ranch. As for Iznogoud, his centred around The Bard and his legacy. gerous cannibals – and they become the future he doesn’t want to happen. -

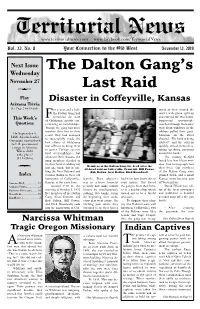

The Dalton Gang's Last Raid

Territorial News www.territorialnews.com www.facebook.com/TerritorialNews Vol. 33, No. 8 Your Connection to the Old West November 13, 2019 Next Issue The Dalton Gang’s Wednesday November 27 Last Raid Play Disaster in Coffeyville, Kansas Arizona Trivia See Page 2 for Details or a year and a half, nized as they crossed the the Dalton Gang had town’s wide plaza, split up This Week’s Fterrorized the state and entered the two banks. of Oklahoma, mostly con- Suspicious townspeople Question: centrating on train holdups. watched through the banks’ Though the gang had more wide front windows as the murders than loot to their robbers pulled their guns. On September 4, credit, they had managed Someone on the street 1886, Apache leader to successfully evade the shouted, “The bank is being Geronimo surrendered to U.S. government best efforts of Oklahoma robbed!” and the citizens troops in Arizona. law officers to bring them quickly armed themselves, Where did it to justice. Perhaps success taking up firing positions take place? bred overconfidence, but around the banks. (14 Letters) whatever their reasons, the The ensuing firefight gang members decided to lasted less than fifteen min- try their hand at robbing not utes. Four townspeople lost Members of the Dalton Gang lay dead after the just one bank, but at rob- ill-fated raid on Coffeyville. From left: Bill Power, their lives, four members bing the First National and Bob Dalton, Grat Dalton, Dick Broadwell. of the Dalton Gang were Index Condon Banks in their old gunned down, and a small hometown of Coffeyville,, feyville. -

Le Mystère Morris

Le mystère Morris Qui connaît Morris ? Que sait-on de la vie et de la personnalité du créateur de Lucky Luke ? A vrai dire, pas grand-chose. Jusqu'à la parution en décembre dernier de L'Art de Morris (1) , il n'y avait pas d'ouvrage de référence. "En préparant ce livre, nous avons été frappés par l'absence de documentation, quand, dans le même temps, on pourrait remplir une bibliothèque avec tout ce qui a été écrit sur Hergé, souligne Jean-Pierre Mercier, conseiller scientifique au musée de la BD d'Angoulême et commissaire de l'exposition qui lui est consacrée. Pour un auteur de cette importance, c'est incompréhensible, il y a un mystère Morris. "Certes, le dessinateur belge n'était pas un client facile. Comme souvent chez ceux de sa génération, les épanchements n'étaient pas son fort, mais, même pour ses pairs, il faisait figure de Martien. "Pour vivre heureux, vivons caché." Il avait fait sienne cette devise, fuyait les mondanités et n'aimait guère les médias. Disparu en 2001, à l'âge de 78 ans, l'homme donnait des interviews au compte-gouttes et préférait rester devant sa télé à dessiner des caricatures plutôt que d'y montrer sa bobine. Idem pour les rares expositions dont il a fait l'objet, car il répugnait autant à prêter ses planches et ses dessins originaux qu'à les voir accrochés aux murs. Curieusement, cet homme qui, dans les années 1960, plaidait pour la reconnaissance de la bande dessinée et fut l'un des premiers à parler de "neuvième art", s'agaçait de ce qu'elle était devenue la décennie suivante. -

Ebook Download Spirou & Fantasio Vol.10

SPIROU & FANTASIO VOL.10: VIRUS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tome | 48 pages | 07 Aug 2016 | CINEBOOK LTD | 9781849182973 | English | Ashford, United Kingdom Spirou & Fantasio Vol.10: Virus PDF Book Books will be free of page markings. Disable this feature for this session. Aventure en Australie , View 1 excerpt, cites background. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Virus , written by Tome and drawn by Janry , is the 33rd album of the Spirou et Fantasio series, and the first to come from this creative team, carrying on the series after the work of previous authors. Whilst it was nice to see an opener with Fantasio undertaking the heroics rather than Spirou, this wasn't my favourite outing from the duo - both writers and characters - and not a volume I'm likely to pick up again, sadly. The Count of Champignac can help, but only if he has access to a very rare toxin — one that is stored, for example, in that mysterious ice base, where more patients await Wong and R. Technical Specs. ABSTRACT Although coronaviruses are known to infect various animals by adapting to new hosts, interspecies transmission events are still poorly understood. Spirou et Fantasio. Trailers and Videos. An icebreaker has unexpectedly moored in the port of Le Havre where it has been put into quarantine. Trade Paperbacks Books. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. The story was initially serialised in Spirou magazine before being released by Dupuis as a hardcover album in Want to Read saving…. Enter the URL for the tweet you want to embed. -

Lucky Luke: Stagecoach V. 25 Free Ebook

FREELUCKY LUKE: STAGECOACH V. 25 EBOOK Goscinny,Morris | 48 pages | 16 Feb 2011 | CINEBOOK LTD | 9781849180528 | English | Ashford, United Kingdom Lucky Luke Lucky Luke 25 - The Stagecoach. ISBN: In Stock. £ inc. VAT. Lucky Luke (english version) - volume 25 - The Stagecoach book. Read reviews from world's largest community for readers. Plagued by constant bandit attac. Lucky Luke is a Western bande dessinée series created by Belgian cartoonist Morris in This started with the story "Des rails sur la Prairie," published on 25 August in Spirou. Ending a long Lucky Luke contre Pat Poker, (Lucky Luke versus Pat Poker); 6. La Diligence, (The Stagecoach); Lucky Luke Adventure GN (2006-Present Cinebook) comic books Lucky Luke is a Western bande dessinée series created by Belgian cartoonist Morris in This started with the story "Des rails sur la Prairie," published on 25 August in Spirou. Ending a long Lucky Luke contre Pat Poker, (Lucky Luke versus Pat Poker); 6. La Diligence, (The Stagecoach); Lucky Luke (CB) # Lucky Luke Versus Pat Poker. By: Cinebook Original Cover, Cinebook: Lucky Luke (CB) # The Stagecoach. Bull Lucky Luke (CB). La Diligence is a Lucky Luke adventure written by Goscinny and illustrated by Morris. It is the 28th book in the series and was originally published in French in , and in English by Cinebook in as The Stagecoach. This Franco- Belgian comics–related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. v · t · e. Lucky Luke Vol. 25: The Stagecoach Sep 7, Lucky luke, fastest gun in wild west trying hes best protectict innocents from criminals. -

Découvrez La Fiche PHILIPPE BERTHET & JEAN-LUC FROMENTAL

EXPOSITION PHILIPPE BERTHET & JEAN-LUC FROMENTAL FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DE LA BANDE DESSINÉE D’ANGOULÊME UN PARTENARIAT FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DE LA BANDE DESSINÉE D’ANGOULÊME ET SNCF GARES & CONNEXIONS En 2021, le Festival International de la Bande Filiale de SNCF Réseau en charge de la gestion, de Dessinée d’Angoulême continue de célébrer l’exploitation et du développement des 3 030 gares encore et toujours la bande dessinée dans toute sa françaises, SNCF Gares & Connexions, spécialiste de créativité et sa diversité. Avec la conviction militante la gare, s’engage pour ses 10 millions de voyageurs et que les gares sont des lieux de vie à part entière, visiteurs quotidiens à constamment améliorer la qualité SNCF Gares & Connexions continue d’offrir à ses voyageurs de l’exploitation, inventer de nouveaux services et des expositions culturelles où le 9e Art prend toute sa place. moderniser le patrimoine. Son ambition : donner envie Leurs ambitions respectives les réunissent donc de gare pour donner envie de train. Née de la conviction naturellement pour imaginer, en lien avec la Nouvelle- que les gares sont des lieux de vie à part entière, SNCF Aquitaine, terre d’accueil du Festival d’Angoulême, une Gares & Connexions enrichit ces « villages urbains » action au sein des gares d’une envergure sans précédent, afin de contribuer à la diffusion de la culture auprès de par sa dimension et son ambition. Ainsi, l’intégralité des tous les publics. Chaque année plus de 100 expositions, Sélections Officielles 2021 du Festival d’Angoulême – soit 75 interventions et manifestations artistiques sont ainsi créations d’autrices et d’auteurs – est aujourd’hui exposée conçues sur-mesure pour les gares sur l’ensemble du dans 40 gares partout en France. -

Jeu-Concours Rock Mastard

CONCOURS PRIX ATOMIUM – SPIROU EDITION 2020 RÈGLEMENT ARTICLE 1 : SOCIÉTÉ ORGANISATRICE LES ÉDITIONS DUPUIS, Société Anonyme de droit belge, immatriculée au Registre des Personnes Morales de Charleroi sous le numéro d’entreprise 0429 160 563, dont le siège social est établi au 52, rue Destrée à 6001 Marcinelle, dûment représentée par Julien Papelier en sa qualité d’Administrateur Délégué (ci-après dénommée « DUPUIS »), organise un concours à l’occasion du Prix Atomium – Spirou Edition 2020 dont les conditions sont indiquées dans le présent règlement (ci-après dénommé le « Concours »). ARTICLE 2 : PARTICIPATION 1. Ce Concours est ouvert à toute personne physique. Sont exclues les personnes ayant participé à l’élaboration directe du Concours (les membres de la société DUPUIS). 2. Pour les personnes mineures souhaitant participer, les parents ou le tuteur légal déclarent, par le fait de la participation au Jeu Concours, qu’ils en approuvent le règlement. La Société Organisatrice se réserve le droit, lors de la désignation des gagnants, de faire approuver le présent règlement par un parent ou un tuteur légal si une personne mineure a été choisie parmi les gagnants. 3. Toutes les éventuelles difficultés pratiques d’interprétation ou d’application seront tranchées par la société organisatrice, DUPUIS. 4. Les coordonnées incomplètes, non conformes au règlement ou reçues après la date limite de participation ne seront pas prises en considération. 5. En dehors des demandes de règlement, il ne sera répondu à aucune demande écrite ou téléphonique concernant le fonctionnement de ce Concours. ARTICLE 3 : ACCÈS ET DURÉE 1. Le Concours est ouvert du 22 juin 2020 à 00h01 au 31 août 2020 à 23h59.