Cyberbullying 2.0: a Schoolhouse Problem Grows Up

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nikki Heat Novels by “Richard Castle”

The Nikki Heat novels by “Richard Castle” Heat Wave [2009] of their unresolved romantic conflict and crackling sexual tension fills the air as Heat and Rook embark on a search for a killer among celebrities and mobsters, singers and hookers, pro A New York real estate tycoon plunges to his athletes and shamed politicians. This new explosive case brings death on a Manhattan sidewalk. A trophy on the heat in the glittery world of secrets, cover-ups, and wife with a past survives a narrow escape scandals. from a brazen attack. Mobsters and moguls, with no shortage of reasons to kill, trot out their alibis. And then, in the suffocating grip Heat Rises [2011] of a record heat wave, comes another shocking murder and a sharp turn in a tense journey into the dirty little secrets of the The bizarre murder of a parish priest at a New wealthy. Secrets that prove to be fatal. Secrets that lay hidden York bondage house opens Nikki Heat’s most in the dark until one NYPD detective shines a light. thrilling and dangerous case so far, pitting her against New York’s most vicious drug lord, an Mystery sensation Richard Castle, blockbuster author of the arrogant CIA contractor, and a shadowy death wildly best-selling Derrick Storm novels, introduces his newest squad out to gun her down. And that is just the tip of the character, NYPD Homicide Detective Nikki Heat. Tough, sexy, iceberg that leads to a dark conspiracy reaching all the way to professional, Nikki Heat carries a passion for justice as she leads the highest level of the NYPD. -

Plastic Bag Law Activist Toolkit 2019 Surfrider Foundation’S Plastic Bag Law Activist Toolkit for U.S

Plastic Bag Law Activist Toolkit 2019 Surfrider Foundation’s Plastic Bag Law Activist Toolkit for U.S. Cities & States Supplement to Surfrider’s Rise Above Plastics Activist Toolkit January 2019 Written and Compiled by: Jennie Romer, Esq., Founder of PlasticBagLaws.org, in partnership with Surfrider Foundation Table Of Contents I. Introduction: How to Use This Toolkit II. Types of Plastic Bag Laws: a. Why Straight Plastic Bag Bans Are Problematic b. Recommended U.S. Bag Law Structures: Ban/Fee Hybrids and Fee on All Bags c. Non-Recommended Plastic Bag Law Structures d. Important Clauses to Consider in Drafting Bag Laws e. Map of Bag Laws in the U.S III. Preemption: Watch Out That Local Bag Laws Don’t Get Blocked by State Legislation IV. Best Statistics to Include in Your Bag Law Campaign a. Harmful Effects of Plastics & Plastic Bags b. Studies Show Bag Fee Laws and Ban/Fee Hybrid Laws Are Effective V. Start a Bag Campaign in Your Community a. Build a Campaign in Your Community (Using the RAP Activist Toolkit) b. Typical Bag Law Allies and Opponents VI. Implementing a Bag Law a. Implementation b. Enforcement c. How to Gather Effectiveness Data Appendix: Recommended Online Resources, Sample Local and State Bag Laws The information in this toolkit is not, nor is it intended to be, legal advice. You should consult an attorney for individual advice regarding your specific situation. CONTACT: If you have questions about this toolkit or would like information and/or help with a plastic bag law initiative in your area, please contact: Trent Hodges Shannon Waters Plastic Pollution Manager Healthy Beaches Manager Surfrider Foundation Surfrider Foundation [email protected] [email protected] (208) 863-8486 (415) 470-3409 1 I. -

Castle Season 5 Episode 24 Watch Onl

Castle season 5 episode 24 watch onl Continue Important: You should only upload images that you have created yourself or that you are directly authorized or licensed to download. By clicking on the Publication button, you confirm that the image is fully compliant with the terms of use of the TV.com and that you own all the rights to the image or have permission to download it. Please read the following before downloading Don't download anything that you don't have or is fully licensed to download. Images must not contain sexually explicit content, racial hate material, or other offensive symbols or images. Remember: the abuse of the TV.com system can lead to you being banned from downloading images or from around the site - so, play nicely and respect the rules! Watch Castle Season 5 full episodes with English subtitles Castle season five finale did not disappoint and just as last season was not quite about the murder they have to solve, but about Rick and Beckett. Beckett goes to the FBI interview in Washington without telling Rick. It sets up the whole episode. Beckett tries to hide the interview from everyone, but ryan and Eposito know that something is wrong. At one point, Ryan even suggests that Beckett might be pregnant, but Esposito doesn't want to hear it. As the episode continues, Rick reveals that Beckett was to D.C. to interview and not discuss it with him. Beckett continues to work on the case and ponder his choice. The captain calls Beckett and tells her to take the job. -

From Casa to Castle: Bolivian Architecture in the Evo Era

The Avery Review Max Holleran – From Casa to Castle: Bolivian Architecture in the Evo Era The image of the cholita has preoccupied Bolivia for decades— Citation: Shantel Blakely, “You Are the Weather: Philippe Rahm’s A Sentimental Meteorology,” in sometimes reviled but, recently, renowned. The archetypical cholita is a The Avery Review, no. 14 (March 2016), http:// short, middle-aged woman wearing a long dress with petticoats, a shawl, averyreview.com/issues/14/you-are-the-weather. and an emblematic bowler cap atop her thickly braided hair. She chews on The research for this piece was conducted collaboratively by Max Holleran and Pedro Rodríguez coca leaves and sometimes sells them in small plastic bags. She is often García . seen waiting for buses to and from the Andean countryside, shouldering an absurdly large bundle on her compact frame. If cholitas are taken to signify an actual demographic group, it is Bolivia’s rural poor, who for centuries have kept indigenous languages alive and traded between towns and villages while maintaining a distinguishing country aesthetic. To urban Bolivians, their bowler hats and braids seem to proclaim that cholitas —despite their frequent contact with cities—have not forgotten where they truly come from. Yet these women and their families have lived in informal urban settlements for generations, often suffering everything from official neglect to acts of outright racism. The lives of cholitas changed dramatically with the election of Evo Morales in 2006, along with their neighborhoods—usually vast, high-altitude slums, which are now slowly being fitted with better transportation and public services. -

Anti-Bullying Policy, to Include Cyber-Bullying

Anti-Bullying Policy This School Policy document is available to all pupils, parents and staff; a copy can be obtained on request from the School Office and is freely available on the School’s website. It is made available to all prospective parents when they visit the School and is automatically given to the parents of all new pupils in the New Pupils’ Handbook. Parents of all pupils are reminded of the policy’s existence and availability in Headmaster’s emails to Parents during each academic year. Staff can also use this policy to guide them if they feel bullied or harassed at work. They are protected by the Whistle-blowing Policy. Principles A supportive School environment characterised by warmth and mutual respect is our ambition. This is stressed to all new and existing pupils and staff. This is stated each term by the Headmaster in his beginning of term School address. There is positive involvement from adults and a sense of co-operation and mutual respect between pupils, and between pupils and staff. Individuality is respected and all members of the School must be enabled to flourish without fear. We publicise the stance that pupils have a right not to be bullied and we all have a responsibility to counter bullying. Aims & Objectives The aim of our counter-bullying policy is to ensure that all students and staff that bullying is always unacceptable. All staff, pupils and parents must understand that the negative effects that bullying has on individuals and the School in general. We all encourage an environment where individuals can flourish without fear. -

Group Captain Dr R a J CASTLE Phd MDA BA Afbpss C.Psychol RAF (Retired) BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Group Captain Dr R A J CASTLE PhD MDA BA AFBPsS C.Psychol RAF (Retired) BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES Born in North London, Richard Castle studied Social Science at the University of East Anglia before being commissioned into the Royal Air Force (RAF). He initially undertook postings within the air transport and human resources spheres. Subsequent career highlights included Command of Support Wing at the Hercules C-130 base at RAF Lyneham and Assistant Director Personnel & Resilience Policy where he initiated and evolved the then innovative RAF Resilience & Stress Management Policy. His final RAF tour was within the UK Defence Academy where he was responsible for developing links between Defence and the Higher Education sector. Richard Castle was seriously injured in the Paddington Rail Crash in West London on 5 October 1999. Following this episode, and his treatment for severe burn injuries, he undertook a PhD research project at Cranfield University into the “Psychological Aspects of Burns Trauma” which was completed in 2006. Additionally, he was seconded to the NHS National Burn Care Review Team for 9 months in 2005 to assist in the development of the concept of psychosocial rehabilitation within a holistic NHS Standard for Burn Care. Richard Castle left the RAF in 2012 and is now an independent mental health policy consultant with particular interests in preparing for, and responding to, collective trauma events and in burns rehabilitation. Since July 2017 he has been Director, Clinical & Compliance for the Grenfell Hope Project, a volunteer-based organisation founded with the aim of honing the long-term psychological resilience of the local community following the Grenfell Tower Fire. -

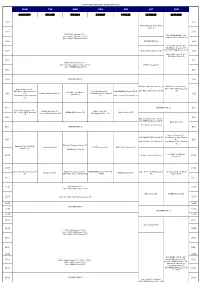

FOX Program Schedule August(Easiness)

FOX Program Schedule August(easiness) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 3.10.17.24.31 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 4:00 4:00 American Horror Story: Freak Show (S) 4:30 4:30 NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / 7th~ NAVY NCIS Season7 (S) / FOX IKKIMI SUNDAY JUL. 25th~ NAVY NCIS Season8 (S) 2nd NAVY NCIS Season12 (S) 5:00 INFORMATION (J) / 5:00 FOX IKKIMI SUNDAY AUG. 9th NCIS:LA Season5 (S) / 5:30 Modern Family Season5 (S) 16th NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) 5:30 / 23rd Castle Season6 (S) / 30th Battle Creek (S) 6:00 6:00 Sleepy Hollow Season2 (S) / 13th~ Da Vinci's Demons Season2 (S) / BONES Season9 (B) 27th~ BONES Season8 (S) 6:30 6:30 7:00 INFORMATION (J) 7:00 Da Vinci's Demons Season2 (S) NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / New Girl Season4 (S) / / 9th~ NAVY NCIS Season12 24th Modern Family Season5 New Girl Season4 (S) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) 29th Major Crimes Season3 (S) (S) How I Met Your Mother (S) / Modern Family Season5 (S) 27th Modern Family Season5 / 7:30 Season5 (S) 7:30 31st Modern Family Season6 (S) 28th 2 Broke Girls Season2 (S) (S) 8:00 INFORMATION (J) 8:00 NAVY NCIS Season11 (S) / NCIS:LA Season5 (S) / Battle Creek (B) / 10th~ NAVY NCIS Season12 HOMELAND Season1 (S) Castle Season 6 (S) 11th~ NCIS:LA Season6 (S) 27th Wayward Pines (S) (S) 8:30 8:30 New Girl Season4 (S) (~9:00) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) Battle Creek (S) / 8th~ NCIS:LA Season6 (S) 9:00 INFORMATION (J) 9:00 New Girl Season4 (S) / THE SIMPSONS Season26 (S) 23rd Modern Family Season5 9:30 / (S) / 9:30 29th 2 Broke Girls Season2 (S) 30th Modern Family -

Substantial Disruption: an Inside Look at Cyberbullying and First Amendment Rights in Public Schools

Substantial Disruption: An Inside Look at Cyberbullying and First Amendment Rights in Public Schools BY: ROBERT CASTLE* I. INTRODUCTION The freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution exemplify our nation’s commitment to ensuring a liberated, freethinking society of individuals capable of changing the world.1 The lives of Americans, past and present, would be radically different had the Founding Fathers built a society restricting the ability to speak freely, explore different religions and cultures, or navigate the countless genres of thought life has to offer. For generations, the U.S. has been a symbol of tolerance, innovation, and progressive thinking.2 This is not to say, however, that our nation has not faced its share of immense challenges and bouts of controversy. These noble ideals often clash with societal advancements, like technology, which foster problems never intended by our forefathers.3 One of the most controversial issues facing our society today begs the question of whether the freedoms granted by the First Amendment extend to Internet communication.4 On one hand, the Internet has * Loyola University Chicago School of Law, J.D. expected May 2014. 1 See U.S. CONST. amend. I. 2 See United States Founded on Liberty and Freedom, PENN LIVE (Sept. 29, 2009), available at http://www.pennlive.com/letters/index.ssf/2009/05/united_states_founded_on_liber.html (“The right to discuss and disagree without fear of retribution is what makes the United States the great and unique country that it is.”). 3 Privacy Technology, and the USA Patriot Act, SOCIAL THEMES (Jan. 4, 2004), available at http://cs.furman.edu/digitaldomain/themes/privacy/privacy1.html (“Of course, the Founding Fathers could not have anticipated the breadth and depth of changes that circumscribe modern life.”). -

Risk and Culture of Health Portrayal in a U.S. Cross-Cultural TV Adaptation, a Pilot Study

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2019, Volume 7, Issue 1, Pages 32–42 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v7i1.1489 Article Risk and Culture of Health Portrayal in a U.S. Cross-Cultural TV Adaptation, a Pilot Study Darien Perez Ryan * and Patrick E. Jamieson Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.P.R), [email protected] (P.E.J.) * Corresponding author Submitted: 22 March 2018 | Accepted: 17 September 2018 | Published: 5 February 2019 Abstract Because media portrayal can influence adolescents’ health, we assessed the health-related content of a popular tele- novela—a Spanish-language TV soap opera genre—and its widely watched English adaptation. To test our “culture of corruption” hypothesis, which predicts that the English-language adaptation of telenovelas will “Americanize” their con- tent by increasing risky and reducing healthy portrayal on screen, we coded the depictions of five risk variables and five culture of health ones in ten episodes each of “Juana la Virgen” (2002) and its popular English-language counterpart, “Jane the Virgin” (2014). A significant increase was found between the Spanish and English-language shows in the risk category of sexual content and a marginally significant increase was found in violence. “Jane” also had larger numbers of charac- ters modeling alcohol consumption, sex, or violence. Across culture of health variables, “Juana” and “Jane” did not exhibit significant differences in the amounts of education-related content, social cohesion, and exercise at the episode level. However, “Jane” had significantly more unhealthy food content (specifically, fats, oils, and sweets and takeout food) and more pro-health messaging than did “Juana.” “Jane” also had a larger amount of modeled food/beverage consumption. -

Castle Academy Tuition Payment Schedule

Castle Academy Tuition Payment Schedule Effective 06/2019 5 4 3 2 Program/Age Days/Week Days/Week Days/Week Days/Week Tuition Tuition Tuition Tuition Infant $1185/month 6 Weeks – 15 Months $1505/month $1365/month $(279/week) $955/month 6:00 – 6:00 ($354/week) ($321/week) Must include ($224/week) Monday and/or Friday Toddler/2-Year-Old Full Day $1045/month 16 Months – 3 Years $1335/month $1215/month ($245/week) $845/month 6:00 – 6:00 ($314/week) ($285/week) Must include ($198/week) Monday and/or Friday Full Day Preschool 2.5 Years – 3 Years $1195/month $1085/month $945/month $795/month and potty-trained ($281/week) ($255/week) ($223/week) ($187/week) 6:00 – 6:00 Full Day / Pre K $850/month 3 Years – 6 Years $1060/month $955/month ($200/week) $745/month 6:00 – 6:00 ($249/week) ($225/week) Must include ($175/week) Monday and/or Friday Half Day Preschool $525/month 3 Years – 6 Years $725/month $625/month ($124/week) $425/month 9:00 to 3:00 ($171/week) ($147/week) Must include ($100/week) August and May are billed as full Monday and/or months regardless of start or end date. Friday School Age Tuition Child Care Tuition includes: Diapers and wipes for infants and toddlers Before & After School Age $22/Day Breakfast before 7:00 a.m., Lunch w/Transportation Mid-morning / afternoon Snacks Before or After School Age $15/Day w/Transportation Kindergarten-6th Grade School Age Tuition includes: In-Service Day/Summer $38/Day Transportation, snacks, fieldtrips (No lunch provided) Additional day for any schedule $75 per day Initial Deposit: $100.00 -- one child $200.00 – family If more than 1 month prior to enrollment, ½ month tuition Family Discount: 10% off the lower monthly rate Tuition is billed monthly and is due in full by the 1st of each month. -

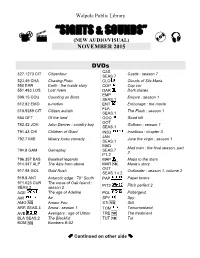

November 2015

Walpole Public Library “SIGHTS & SOUNDS” (NEW AUDIO/VISUAL) NOVEMBER 2015 DVDs CAS 327.1273 CIT Citizenfour Castle : season 7 SEAS.7 523.49 CHA Chasing Pluto CLO Clouds of Sils Maria 550 EAR Earth : the inside story COP Cop car 551.483 LOS Lost rivers DAR Dark places EMP 598.15 COU Counting on Birds Empire : season 1 SEAS.1 612.82 EMO e-motion ENT Entourage : the movie FLA 618.9289 CIT Citizen autistic The Flash : season 1 SEAS.1 664 OFT Of the land GOO Good kill GOT 782.42 JOH John Denver : country boy Gotham : season 1 SEAS.1 791.43 CHI Children of Giant INS3 Insidious : chapter 3 JAN 792.7 MIS Misery loves comedy Jane the virgin : season 1 SEAS.1 MAD Mad men : the final season, part 794.8 GAM Gameplay SEAS.7 2 PT.2 796.357 BAS Baseball legends MAP Maps to the stars 914.947 ALP The Alps from above MAR NR Marie’s story OUT 917.98 GOL Gold Rush Outlander : season 1, volume 2 SEAS.1 v.2 919.8 ANT Antarctic edge : 70 South PAP Paper towns 971.623 CUR The curse of Oak Island : Pitch perfect 2 SEAS.2 season 2 PIT2 AGE The age of Adeline POL Poltergeist AIR Air SPY Spy AMO NR Amour Fou STI NR Still ARR SEAS.3 Arrow : season 1 TOM Tomorrowland AVE Avengers : age of Ultron TRE NR The treatment BLA SEAS.2 The Blacklist TUT NR Tut BOM NR Bombers B-52 Continued on other side 2 Walpole Public Library NEW AUDIO/VISUAL 2015 CDs BOO SHOW Original Broadway Cast The Book of Mormon Books on CD 152.4 DOU Anxious HIGGINS If you only knew 158 BRO Rising strong KARON Come rain or come shine 813.54 GAB The outlandish LAGERCRANT The girl in the spider’s web companion Z BALOGH Only a kiss MACOMBER Dashing through the snow BANVILLE The blue guitar MCCALLSMITH The novel habits of happiness The gilded life of Christmas in Mustang Creek BRUNKHORST MILLER Matilda Duplaine BURDETT The Bangkok asset MOSS Minute zero CARR Wildest dreams PATTERSON Murder house CHILD Make me PATTERSON The murder house CHO Sorcerer to the crown PERRY Corridors of the night CLARK The Jezebel remedy SLAUGHTER Pretty girls DOIG Last bus to wisdom STEWART Girl waits with a gun FRANZEN Purity TUCKER Murder, D.C. -

Mexican Melodrama in the Age of Netflix: Algorithms for Cultural

Mexican Melodrama in the Age of Netflix: Algorithms for Cultural Proximity Melodrama mexicano en la era de Netflix: ELIA MARGARITA algoritmos para la proximidad cultural CORNELIO-MARÍ1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2020.7481 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5495-1870 By using algorithms to track the data of their users in Mexico, Netflix has managed to solve the equation of cultural proximity. Since 2015 it has produced original series that include melodramatic traits, even if they align with genres like comedy, biopic and political thriller. Applying industrial and textual analysis, this article argues that Netflix has established a love-hate relationship with Mexican melodrama, making fun of its conventions but using them nevertheless. It concludes that algorithms have the potential to transform Internet TV providers into competitors for local producers. KEYWORDS: Netflix, InternetTV , algorithms, melodrama, cultural proximity, telenovela. Netflix ha resuelto la ecuación de la proximidad cultural en México utilizando algoritmos para monitorear los datos de sus usuarios. Desde 2015 ha producido series originales que muestran rasgos melodramáticos a pesar de pertenecer a géneros como la comedia, la biografía o la acción de trasfondo político. Con base en un análisis textual y de la in- dustria, este artículo sostiene que Netflix ha establecido una relación de amor-odio con el melodrama mexicano, burlándose de sus convenciones pero usándolas al mismo tiempo. Se concluye que el uso de algoritmos tiene el potencial de transformar a los proveedores de televisión por Internet en competidores de los productores locales. PALABRAS CLAVE: Netflix, televisión por Internet, algoritmos, melodrama, proximidad cultural, telenovela.