Aicardi Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practitioners' Section

407 408 GENETICS OF MENTAL RETARDATION [2] [4] PRACTITIONERS’ SECTION epiphenomena. A specific cause for mental a group heritability of 0.49. The aetiology of retardation can be identified in approximately idiopathic mental retardation is usually 80% of people with SMR (IQ<50) and 50% of explained in terms of the ‘polygenic GENETICS OF MENTAL RETARDATION people with MMR (IQ 50–70). multifactorial model.’ The difficulty is that there A. S. AHUJA, ANITA THAPAR, M. J. OWEN are too few studies to provide sufficiently In this article, we will begin by considering precise estimates of the likely role of genes ABSTRACT what is known about the genetics of idiopathic and environment in determining idiopathic mental retardation and then move onto discuss mental retardation. Given the dearth of Mental retardation can follow any of the biological, environmental and psychological events that are capable of producing deficits in cognitive functions. specific genetic causes of mental retardation. published literature we are reliant on Recent advances in molecular genetic techniques have enabled us to understand attempting to draw conclusions from family and more about the molecular basis of several genetic syndromes associated with mental Search methodology twin studies, most of which are very old and retardation. In contrast, where there is no discrete cause, the interplay of genetic Electronic searching was done and the which report widely varying recurrence risks.[5] and environmental influences remains poorly understood. This article presents a relevant studies were identified by searching Recent studies of MMR have shown high rates critical review of literature on genetics of mental retardation. -

ICARE: Interagency Collaborative to Advance Research in Epilepsy 2014 Member Reports

ICARE: Interagency Collaborative to Advance Research in Epilepsy 2014 Member Reports Table of Contents National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) ............................................................... 2 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) ..................................................................................... 4 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) ................................................................... 7 The National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB)................................................ 9 Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) .............. 10 National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) ................................................................................................... 12 Other Federal Participants Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC Epilepsy Program .............................................................................................................................. 13 National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities (NCBDDD) ....................................... 17 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services ................. 20 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Epilepsy Centers of Excellence (ECoE) ......................................... 22 Nongovernmental Organizations American Epilepsy Society (AES) .............................................................................................................. -

Genetic Disorder

Genetic disorder Single gene disorder Prevalence of some single gene disorders[citation needed] A single gene disorder is the result of a single mutated gene. Disorder Prevalence (approximate) There are estimated to be over 4000 human diseases caused Autosomal dominant by single gene defects. Single gene disorders can be passed Familial hypercholesterolemia 1 in 500 on to subsequent generations in several ways. Genomic Polycystic kidney disease 1 in 1250 imprinting and uniparental disomy, however, may affect Hereditary spherocytosis 1 in 5,000 inheritance patterns. The divisions between recessive [2] Marfan syndrome 1 in 4,000 and dominant types are not "hard and fast" although the [3] Huntington disease 1 in 15,000 divisions between autosomal and X-linked types are (since Autosomal recessive the latter types are distinguished purely based on 1 in 625 the chromosomal location of Sickle cell anemia the gene). For example, (African Americans) achondroplasia is typically 1 in 2,000 considered a dominant Cystic fibrosis disorder, but children with two (Caucasians) genes for achondroplasia have a severe skeletal disorder that 1 in 3,000 Tay-Sachs disease achondroplasics could be (American Jews) viewed as carriers of. Sickle- cell anemia is also considered a Phenylketonuria 1 in 12,000 recessive condition, but heterozygous carriers have Mucopolysaccharidoses 1 in 25,000 increased immunity to malaria in early childhood, which could Glycogen storage diseases 1 in 50,000 be described as a related [citation needed] dominant condition. Galactosemia -

A Rare Case of Aicardi Syndrome

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research www.ijhsr.org ISSN: 2249-9571 Case Report Unlike the Textbook Triad: A Rare Case of Aicardi Syndrome Niharika Prasad1, Sanjay Purushothama2 1Senior Resident, Department of Radio-Diagnosis All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna 2Assistant Professor, Department of Radio-Diagnosis, Mysore Medical College and Research Institute, Mysore Corresponding Author: Niharika Prasad ABSTRACT Aicardi syndrome (AS) is an X-linked inherited disorder characterized by infantile spasms, chorioretinal lacunae, and agenesis or hypogenesis of the corpus callosum. Since the description of the first case of Aicardi syndrome in 1965 not many have contributed to the list, hence preserving its rarity. The purpose of this case report was to demonstrate the spectrum of MRI findings and follow up in the course of Aicardi syndrome. Key words: Corpus callosum; agenesis; Aicardi; microcephaly; infant INTRODUCTION limits and CSF testing did not yield any Aicardi syndrome (AS) was first clues to diagnosis. No chromosomal disease described by Jean Aicardi in 1965 and is pattern was discovered on analysis. Detailed characterized by agenesis or hypogenesis of birth and development history was elicited the corpus callosum, chorioretinal lacunae, from parents. No episode of seizures had and early infantile spasms. Most of AS occurred although they confirmed delayed patients develop normally until 3 months of milestones compared to a normal infant. age, and then, epileptic seizures and Plain MRI study of brain and orbits on a developmental delay start. It is an X-linked Siemens Magnetom Avanto 1.5T system dominant genetic disorder and lethal in revealed partial agenesis of corpus callosum males and, therefore, almost exclusively and unilateral optic nerve hypoplasia. -

Soonerstart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions

SoonerStart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions - Appendix O Abetalipoproteinemia Acanthocytosis (see Abetalipoproteinemia) Accutane, Fetal Effects of (see Fetal Retinoid Syndrome) Acidemia, 2-Oxoglutaric Acidemia, Glutaric I Acidemia, Isovaleric Acidemia, Methylmalonic Acidemia, Propionic Aciduria, 3-Methylglutaconic Type II Aciduria, Argininosuccinic Acoustic-Cervico-Oculo Syndrome (see Cervico-Oculo-Acoustic Syndrome) Acrocephalopolysyndactyly Type II Acrocephalosyndactyly Type I Acrodysostosis Acrofacial Dysostosis, Nager Type Adams-Oliver Syndrome (see Limb and Scalp Defects, Adams-Oliver Type) Adrenoleukodystrophy, Neonatal (see Cerebro-Hepato-Renal Syndrome) Aglossia Congenita (see Hypoglossia-Hypodactylia) Aicardi Syndrome AIDS Infection (see Fetal Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) Alaninuria (see Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Deficiency) Albers-Schonberg Disease (see Osteopetrosis, Malignant Recessive) Albinism, Ocular (includes Autosomal Recessive Type) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Brown Type (Type IV) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Negative (Type IA) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Positive (Type II) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Yellow Mutant (Type IB) Albinism-Black Locks-Deafness Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy (see Parathyroid Hormone Resistance) Alexander Disease Alopecia - Mental Retardation Alpers Disease Alpha 1,4 - Glucosidase Deficiency (see Glycogenosis, Type IIA) Alpha-L-Fucosidase Deficiency (see Fucosidosis) Alport Syndrome (see Nephritis-Deafness, Hereditary Type) Amaurosis (see Blindness) Amaurosis -

Case Report: Aicardi Syndrome Presenting As Cleft Lip and Palate

Case Report Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg Volume 3 Issue 5 - May 2017 DOI: 10.19080/OAJNN.2017.03.555625 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Juan Pablo Appendino Case Report: Aicardi Syndrome presenting as Cleft Lip and Palate Danielle Weidman1 and Juan Pablo Appendino2* 1Paediatric Resident, The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Canada 2Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary, Canada Submission: March 02, 2017; Published: May 30, 2017 *Corresponding author: Juan Pablo Appendino, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Paediatrics, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Pediatric Epilepsy and Child Neurology, Alberta Children’s Hospital 2888 Shaganappi Trail NW, Calgary, AB T3B 6A8, Tel: Fax: 403-955-7609; Pager: 403-212-8223 #14691; Email: Abstract Aicardi syndrome (AS) is an unusual neurological disorder that was originally described in 1965 by Dr. Jean Aicardi. This disorder is characterized by a triad of abnormalities: agenesis of the corpus callosum, chorio retinal lacunae, and infantile spasms. There are infrequent reports of cleft lip and palate in patients with AS. This report details a case of a patient with AS who presented with left-sided cleft lip and palate and right eye coloboma to her pediatrician; however, the diagnosis of AS was not suspected until later when the she presented with appropriateInfantile Spasms. diagnosis. The discussion will focus on the existing literature of AS with cleft lip and palate and ophthalmological findings offering a learning point to the pediatric community in regards with her clinical, neuroimaging and neurophysiological findings for an earlier and Introduction Aicardi syndrome (AS) is a relatively rare disease that was presents to the pediatrician for medical advice. -

The Genetics of Rett Syndrome

TheThe GeneticsGenetics ofof RettRett SyndromeSyndrome JohnJohn ChristodoulouChristodoulou Head, NSW Rett Syndrome Research Unit Western Sydney Genetics Program, Children’s Hospital at Westmead Discipline of Paediatrics & Child Health, University of Sydney ClinicalClinical DiagnosisDiagnosis •• specificspecific developmentaldevelopmental profileprofile basedbased onon aa consistentconsistent constellationconstellation ofof clinicalclinical featuresfeatures •• diagnosticdiagnostic criteriacriteria developeddeveloped •• classicalclassical andand variantvariant RTTRTT phenotypesphenotypes – atypical Rett syndrome – “speech preserved” variant – congenital onset variant – male Rett syndrome equivalent GeneticsGenetics ofof RettRett SyndromeSyndrome X:X: autosomeautosome translocations:translocations: - t (X; 22) - Xp11.22 - t (X; 3) - Xp21.3 Deletions:Deletions: - del (3) (3p25.1 - p25.2) - del (13) (13q12.1 - q21.2) mtDNAmtDNA mutationmutation screening:screening: - 16S rRNA - A2706G (1 patient & mother) ExclusionExclusion mappingmapping inin familialfamilial cases:cases: (incl. Brazilian family with 3 affected sisters) - gene likely to be in Xq28 or Xpter “Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG binding protein 2” (Amir et al, Nature Genet 1999: 23; 185 - 188) 6 mutations identified in 21 sporadic classical cases - 4 de novo missense mutations in methyl-binding domain (MBD) - 1 de novo frame-shift mutation in transcription repression domain (TRD) - 1 de novo nonsense mutation in TRD MECP2MECP2 MutationsMutations -

Genetic Diseases

Genetic Diseases You are now familiar with the role of DNA in our bodies; how it is replicated and expressed within a cell. You also know how DNA can accumulate mutations and what this can do to the protein that may be coded by that sequence. Also keep in mind how DNA is organized into multiple chromosomes. During mitosis and meiosis, it is crucial that chromosomes be separated equally between the daughter cells. In our current unit, we will discuss how traits (carried on our chromosomes) are inherited from one generation to the next. You will learn how to predict the probability of a trait being passed on and how this information is practical for potential parents and genetic counselors. Through this assignment, you will choose a genetic disease which you will research. You will create a wiki page about your disease and post it on the Pingry server. In addition you will give a brief (5 minute) oral presentation to the class. And provide a brochure of your disease and syndrome. During your research, look for the following: • What is the genetic cause of the disease? • What gene is mutated or chromosome altered? • What is the pattern of inheritance of the disease (dominant or recessive)? • What are the symptoms and characteristics of the disease? • What are the current methods of treatment/cure for the disease? Guidelines for the wiki page that you will be creating: • Treat your wiki as if you are presenting the information live to a group of people. • Create your own work. If you use material from another source, be certain that you give proper credit to that source. -

Genetic Disorder Pamphlet Project

Genetic Disorder Pamphlet Project Purpose: To create a pamphlet that describes a specific genetic disorder, much the same as a pamphlet found in a doctors office. G rading: Y ou w ill be graded on the follow ing four areas: - N eatness 20% - Cover all 6 folds 10% - Pictures 10% - Information 60% The information w ill be broken into five sections: how the disorder is diagnosed, possible treatments, w hat causes the disorder, current research, and five interesting facts. W here do I find Information? - Y ou are required to have at least one book source and no more than tw o w eb sources. Y ou must include a w orks cited section on the back of the pamphlet, w hich displays the sources you used for your information. - Pictures are good to have, but remember that most of your grade is based on the information you find. W rite w ell, because you w ill be docked points for poor grammar. W hat G enetic D isorders Can I Research? There is a list of some possible disorders listed on the next tw o folds. If you w ould like to research a disorder not listed, all you need to do is ask and get the okay from the teacher. Possible D isorders: Long QT Syndrome Marfan Syndrome Achondroplasia Moebius Syndrome Achromatopsia Mucopolysaccaridosis (MPS) Acid Maltase Deficiency Nail Patella Syndrome Adrenoleukodystrophy Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus Aicardi Syndrome Neurofibromatosis Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Niemann-Pick Disease Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Osteogenesis Imperfecta Apert Syndrome Progeria Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia Proteus -

Genomeposter2009.Pdf

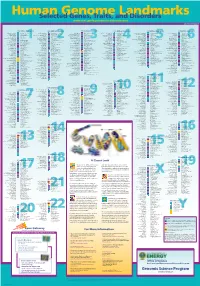

Fold HumanSelected Genome Genes, Traits, and Landmarks Disorders www.ornl.gov/hgmis/posters/chromosome genomics.energy. -

Aicardi Syndrome: MR Assessment of Brain Structure and Myelination

532 Aicardi Syndrome: MR Assessment of Brain Structure and Myelination Margaret Anne Haii-Craggs,1 Michael Geoffrey Harbord,2 John Paul Finn, 1 Edward Brett,2 and Brian Ernest Kendall 1 Aicardi syndrome is characterized by the combination , in An EEG performed after starting ACTH therapy showed high girls, of agenesis of the corpus callosum, epilepsy, and typical amplitude slow waves over both hemispheres with freq uent sharp choroidal lacunae. Other associated brain abnormalities that waves. An intermittent burst suppression pattern was clinically as have been described include gross asymmetry of the cerebral sociated with flexor spasms. MR performed at 6 months showed that the body of the corpus callosum was small and the genu and splenium hemispheres, irregular ventricular contours caused by sub were absent (Fig. 1A) . A midline cyst was shown lying posterior to ependymal heterotopic nodules, cysts in the hemispheres and the corpus callosum , extending behind and above the third ventricle, the posterior fossa, cerebellar hypoplasia, papillomas of the of signal intensity higher than CSF on both T1- and T2-weighted SE choroid plexus, holoprosencephaly, microphthalmia, and neu images. The origin of the cyst was unknown, and was possibly ronal migrational abnormalities [1-5]. Detailed neuropatho hamartomatous (Figs. 1A and 1 B). Myelination was appropriate for logic reports have not previously described abnormal myeli age, being symmetrically present in the middle cerebellar peduncles, nation as a feature of this syndrome [1-3]. We report three the posterior limb of the internal capsule, and the cerebellar white cases in which MR Imaging provided detailed information on matter (Figs. -

Neuronal Maturation Defect in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells from Patients with Rett Syndrome

Neuronal maturation defect in induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with Rett syndrome Kun-Yong Kim, Eriona Hysolli, and In-Hyun Park1 Department of Genetics, Yale Stem Cell Center, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06520 Edited* by Sherman M. Weissman, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved July 13, 2011 (received for review December 29, 2010) Rett syndrome (RTT) is one of the most prevalent female neuro- MeCP2 recapitulates the RTT symptoms of the whole-body KO developmental disorders that cause severe mental retardation. mouse, implicating an essential role for MeCP2 in neurons (11). Mutations in methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) are mainly As neuronal stem cells differentiate into neurons, MeCP2 ex- responsible for RTT. Patients with classical RTT exhibit normal pression gradually increases. Recently, glial cells were also found – to express MeCP2 and to play an important role in pathogenesis development until age 6 18 mo, at which point they become – symptomatic and display loss of language and motor skills, pur- of RTT (12 14). Regardless of the essential information on RTT disease poseful hand movements, and normal head growth. Murine ge- obtained from murine models, the phenotypes of the MeCP2 netic models and postmortem human brains have been used to null KO mouse are not identical to the human phenotypes. study the disease and enable the molecular dissection of RTT. In Homozygous MeCP2 null female mice are born to term and this work, we applied a recently developed reprogramming ap- survive until 4 wk after birth, and heterozygous MeCP2 female proach to generate a novel in vitro human RTT model.