Nothing Compares 2 U: Notes on Sincerity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

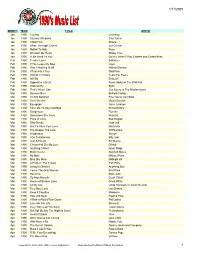

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Prince 20Ten Complete European Summer Tour Recordings Vol

Prince 20Ten Complete European Summer Tour Recordings Vol. 10 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Funk / Soul / Pop Album: 20Ten Complete European Summer Tour Recordings Vol. 10 Country: Germany MP3 version RAR size: 1482 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1272 mb WMA version RAR size: 1410 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 916 Other Formats: VOC WAV AUD MOD TTA AAC DXD Tracklist Yas Arena, Yas Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, November 14, 2010 1-1 Let's Go Crazy 1-2 Delirious 1-3 Let's Go Crazy (Reprise) 1-4 1999 1-5 Little Red Corvette 1-6 Controversy / Oh Abu Dhabi (Chant) 1-7 Sexy Dancer / Le Freak 1-8 Controversy (Coda) / Housequake (Chant) 1-9 Angel 1-10 Nothing Compares 2 U 1-11 Uptown 1-12 Raspberry Beret 1-13 Cream (Includes For Love) 1-14 U Got The Look 1-15 Shhh 1-16 Love...Thy Will Be Done 1-17 Keyboard Interlude 1-18 Purple Rain 2-1 Kiss 2-2 Prince And The Girls Pick Some Dancers 2-3 The Bird 2-4 Jungle Love 2-5 A Love Bizarre (Aborted) 2-6 A Love Bizarre (Nicole Scherzinger On Co-Lead Vocals) 2-7 Dance (Disco Heat) 2-8 Baby I'm A Star 2-9 Sometimes It Snows In April 2-10 Peach Soundcheck, Gelredome, Arnhem, November 18, 2010 2-11 Scandalous / The Beautiful Ones (Instrumental Takes) 2-12 The Beautiful Ones (Various Instrumental Takes) 2-13 Nothing Compares 2 U (3 Instrumental Takes) 2-14 Car Wash (Instrumental Groove) / Controversy (Instrumental) 2-15 Hot Thing (Extended Jam, Overmodulated) 2-16 Hot Thing (Extended Jam, Clean Part) 2-17 Flashlight (Instrumental) 2-18 Insatiable 2-19 Insatiable / If I Was Your Girlfriend -

C4 Music Guide

C4 Music Rights and Clearances Guide Part 1 – What do I need to clear and how much does it cost? Page. 1. Recording, Publishing and Performers Rights explained 3 2. Publishing a) Clearing publishing rights under the IPC scheme 3 b) Paying for publishing rights under the IPC scheme 4 c) Publishing Rights rate card 5 d) What about Broadcast rights? 7 3. Recordings a) Clearing recording rights 7 b) Paying for recording rights 8 4. Performers a) Clearing performers’ rights 8 b) Paying for performers’ rights 8 5. Cue Sheets and Music License forms 9 Part 2 – Clearing outside of C4’s blanket deals 1. Exceptions and Restrictions a) Respect the blankets! 11 b) Exempted artists 11 c) Appropriate Usage 11 d) Titles/Signature Music 12 e) Sponsorship and Advertising 12 f) Dramatico Musical Works 13 2. Help! My track won’t clear! a) I can’t find the track on the PRS/PPL databases 13 b) Copyright control / Non Society shares 13 c) International collecting societies 14 d) Out of copyright / Traditional / Public Domain 14 e) Sample suspense 15 3. How to clear non PRS/PPL repertoire a) Things to consider 16 i) Time Consuming 16 ii) Problematic 16 iii) Confusing 16 iv) Costly 16 b) Alternatives i) Use another track 17 ii) Use a library track 17 c) Negotiating a license i) Clearing PRS/PPL repertoire 17 ii) Clearing Non PRS/PPL repertoire 18 iii) MFN (Most Favoured Nations) 18 iv) Await Claim 18 1 Part 3 – Specialist music uses 1. Other music uses Cont…… a) Live performances by cast members 19 b) Live performances by artists or bands 19 c) Music Videos VPL 19 d) Music based shows 20 e) Dramatico Musical Works 20 f) Promos and Trailers 21 g) Online and ‘New Make’ 21 h) Clearing for DVD and DTO i) Publishing 21 ii) Recordings 22 iii) Reporting 22 2. -

Bad Habit Song List

BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song 4 Non Blondes Whats Up Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Crazy Alanis Morissette You Learn Alanis Morissette Uninvited Alanis Morissette Thank You Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette Hand In My Pocket Alice Merton No Roots Billie Eilish Bad Guy Bobby Brown My Prerogative Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Aguilera Fighter Corey Hart Sunglasses at Night Cyndi Lauper Time After Time David Guetta Titanium Deee-Lite Groove Is In The Heart Dishwalla Counting Blue Cars DNCE Cake By the Ocean Dua Lipa One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Dua Lipa Break My Heart Ed Sheeran Blow BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Elle King Ex’s & Oh’s En Vogue Free Your Mind Eurythmics Sweet Dreams Fall Out Boy Beat It George Michael Faith Guns N’ Roses Sweet Child O’ Mine Hailee Steinfeld Starving Halsey Graveyard Imagine Dragons Whatever It Takes Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Jessie J Price Tag Jet Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jewel Who Will Save Your Soul Jo Dee Messina Heads Carolina, Tails California Jonas Brothers Sucker Journey Separate Ways Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Say Something Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry Dark Horse Katy Perry I Kissed a Girl Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Yoü and I Lady Gaga Telephone BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Lady Gaga Shallow Letters to Cleo Here and Now Lizzo Truth Hurts Lorde Royals Madonna Vogue Madonna Into The Groove Madonna Holiday Madonna Border Line Madonna Lucky Star Madonna Ray of Light Meghan Trainor All About That Bass Michael Jackson Dirty Diana Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson Human Nature Michael Jackson Black Or White Michael Jackson Bad Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Something Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

90'S Medley Rihanna Medley Motown Medley Prince

Adele - Rolling in the Deep Jackson 5 - ABC Outkast - Miss Jackson 90’S MEDLEY Alabama Shakes - Hold on James Brown - Get Up Oa That Thing Outkast - Rosa Parks TLC Alicia Keys - Empire State of Mind James and Bobby Purify - Shake A Tail Feather Patrice Ruschen - Forget Me Nots Usher Alicia Keys - If I Ain’t Got You James Blake - Limit To Your Love Percy Sledge - You Really Got a Hold On Me Montell Jordan Al Green - Let’s Stay Together Jamie XX - Good Times Pharrell – Happy Mark Morrison Al Green - Take Me to the River Janelle Monae - Tightrope Prince – I Wanna Be Your Lover Next Amy Whinehouse - Valerie Jerry Lee Lewis - Great Balls of Fire Prince - Kiss Beck – Where It’s At Justin Timberlake - Can’t Stop The Feeling Ray Charles - Georgia Beyonce – Crazy In Love Justin Timberlake - Rock Your Body R Kelly - Remix to Ignition RIHANNA MEDLEY Beyonce - Love on Top King Harvest - Dancing in the Moonlight Sade - By Your Side What’s My Name Beyonce - Party Kendrick Lamar – If These Walls Could Talk Sade - Smooth Operator We Found Love Bill Withers - Ain’t No Sunshine Leon Bridges - Coming Home Sade - Sweetest Taboo Work Blondie – Rapture Lil Nas X - Old Town Road Sam Cooke - Wonderful World Blood Orange - You’re Not Good Enough Sam Cooke - Cupid Lionel Richie - All Night Long MOTOWN MEDLEY Bob Carlisle/Je Carson - Butterfly Kisses Little Richard - Good Golly Miss Molly Sam Cooke - Twistin’ Your Love Keeps Lifting Me Higher and Higher Bruno Mars - 24k Magic Lizzo - Juice Sam Cooke – You Send Me You Really Got a Hold On Me Bruno Mars - Treasure -

Song List by Artist

AMAZING EMBARRASSONIC Song list by Artist CALIFORNIA LUV 2PAC AND DR.DRE DANCING QUEEN ABBA MAMA MIA ABBA S. O. S. ABBA BIG BALLS AC/DC HAVE A DRINK ON ME AC/DC HELLS BELLS AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC LIVE WIRE AC/DC SIN CITY AC/DC TNT AC/DC WHOLE LOT OF ROSIE AC/DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC CUTS LIKE A KNIFE ADAMS, BRYAN SUMMER OF '69 ADAMS, BRYAN DRAW THE LINE AEROSMITH SICK AS A DOG AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH REMEMBER( WALKING IN THE SAND) AEROSMITH BEAUTIFUL AGUILARA, CHRISTINA LOST IN LOVE AIR SUPPLY MOUNTAIN MUSIC ALABAMA ROOSTER ALICE IN CHAINS ONE WAY OUT ALLMAN BROS RAMBLIN MAN ALLMAN BROS SISTER GOLDEN HAIR AMERICA SHE'S HAVING MY BABY ANKA, PAUL SUGAR, SUGAR ARCHIES AINT SEEN NOTHING YET BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE LET IT RIDE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE TAKIN CARE OF BUSINESS BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE EVERYBODY BACKSTREET BOYS FEEL LIKE MAKIN' LUV BAD CO. GOOD LOVIN' GONE BAD BAD CO. SHOOTING STAR BAD CO. NO MATTER WHAT BADFINGER DO THEY KNOW IT'S X-MAS BAND-AID MANIC MONDAY BANGLES WALK LIKE AN EGYPTIAN BANGLES SATURDAY NIGHT BAY CITY ROLLERS IN MY ROOM BEACH BOYS FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHT TO PARTY BEASTIE BOYS COME TOGETHER BEATLES DAY TRIPPER BEATLES HARD DAYS NIGHT BEATLES LET IT BE BEATLES HELTER SKELTER BEATLES HEY JUDE BEATLES SOMETHING BEATLES TWIST AND SHOUT BEATLES LOSER BECK JIVE TALKIN' BEE GEES www.amazingembarrassonic.com Page 1 9/30/15 AMAZING EMBARRASSONIC Song list by Artist MASSACHUSETTS BEE GEES STAYIN' ALIVE BEE GEES HEARTBREAKER BENATAR, PAT HELL IS FOR CHILDREN BENATAR, PAT HIT ME W/YOUR BEST SHOT -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Mccain-Theatre-Brochure.Pdf

2018 – 2019 2018 – 2019 Chick Corea: Vigilette with The Mavericks: 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 21 Carlitos Del Puerto and Hey! Merry Christmas! ........ 16 7:30 p.m. Friday, Feb. 22 Marcus Gilmore ......................... 4 7:30 p.m. Monday, Nov. 26 2:30 and 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 23 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 13 Judy Collins: Sir James Galway, Flute ..... 28 Trevor Noah ................................ 5 Holiday & Hits ............................17 7:30 p.m. Friday, March 8 7:30 p.m. Friday, Sept. 21 7:30 p.m. Friday, Dec. 7 Switchback The Fabulous Thunderbirds STOMP ......................................... 18 (Wareham Opera House) ........... 28 Featuring Kim Wilson ........... 6 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, Jan. 15 7 and 9:30 p.m. Saturday, March 9 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 27 The Hot Sardines Storm Large & Le Bonheur Black Violin ................................. 7 (Wareham Opera House) ........... 19 (Wareham Opera House) ............29 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 2 7 and 9:30 p.m. Friday, Jan. 18 7 and 9:30 p.m. Saturday, March 23 iLuminate ..................................... 8 imPerfect Dancers Company: The Manhattan Transfer 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 9 Anne Frank — Words From meets Take 6 — The Summit .............................. 30 Emmylou Harris ........................ 9 the Shadow .......................................22 7:30 p.m. Sunday, March 31 7:30 p.m. Friday, Oct. 12 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, Jan. 29 Diana Krall ................................ 31 DHOAD Gypsies of Legally Blonde — 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, April 2 Rajasthan ................................... 10 The Musical ............................... 23 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 16 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 2 The King and I ........................ -

Prince Talks and with the Release of 'Graffiti Bridge,' the Soundtrack to His Forthcoming Movie Musical, the Critics Are Listening

Prince Talks And with the release of 'Graffiti Bridge,' the soundtrack to his forthcoming movie musical, the critics are listening. But don't even try to take notes. Prince performing at Wembley, London, August 22nd, 1990. Graham Wiltshire/Hulton Archive/Getty By Neal Karlen October 18, 1990 The phone rings at 4:48 in the morning. "Hi, it's Prince," says the wide-awake voice calling from a room several yards down the hallway of this London hotel. "Did I wake you up?" Though it's assumed that Prince does in fact sleep, no one on his summer European Nude Tour can pinpoint precisely when. Prince seems to relish the aura of night stalker; his vampire hours have been a part of his mad-genius myth ever since he was waging junior-high-school band battles on Minneapolis's mostly black North Side. "Anyone who was around back then knew what was happening," Prince had said two days earlier, reminiscing. "I was working. When they were sleeping, I was jamming. When they woke up, I had another groove. I'm as insane that way now as I was back then." For proof, he'd produced a crinkled dime-store notebook that he carries with him like Linus's blanket. Empty when his tour started in May, the book is nearly full, with twenty-one new songs scripted in perfect grammar-school penmanship. He has also been laboring on the road over his movie musical Graffiti Bridge, which was supposed to be out this past summer and is now set for release in November. -

Dig If You Will the Picture

Barrelhouse Magazine Dig if You Will the Picture Writers Reflect on Prince First published by Barrelhouse Magazine in 2016. Copyright © Barrelhouse Magazine, 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher. It is illegal to copy this book, post it to a website, or distribute it by any others means without permission. This book was professionally typeset on Reedsy. Find out more at reedsy.com Contents Prince Rogers Nelson v The Beautiful Ones 7 The Birthday Suit 9 Freak 13 When the Cicadas Were Out of Their Fucking Minds 16 Two Poems After Prince 19 Try to Imagine What Silence Looks Like 24 And This Brings Us Back to Pharoah 27 Chant for a New Poet Generation 29 Trickster 31 Let's Go Crazy 36 Seventeen in '84 39 Elegy 41 Could Have Sworn It Was Judgement Day 43 Prince Called Me Up Onstage at the Pontiac Silverdome 47 Backing Up 49 The King of Purple 54 What It Is 55 I Shall Grow Purple 59 Group Therapy: Writers Remember Prince 61 Anthem for Paisley Park 77 Liner Notes 78 Nothing Compares 2 U 83 3 Because They Was Purple 88 Reign 90 Contributors 91 About Barrelhouse 101 Barrelhouse Editors 103 Prince Rogers Nelson June 7, 1958 – April 21, 2016 (art by Shannon Wright) In this life, things are much harder than in the afterworld. In this life, you're on your own. v 1 The Beautiful Ones by Sheila Squillante We used to buy roasted chickens at the Grand Union after school and take them back to Jen’s house.