W H a K a T a N E B U I L T H E R I T a G E S T U D Y P a R T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Annual Report

LION FOUNDATION 2021 ANNUAL REPORT Our aim is to be New Zealand’s leading charitable trust, nationally recognised and respected for helping New Zealanders achieve great things in the community. We value integrity, compelling us to act honestly, ethically and transparently. For 36 years we have been working with NZ communities to make a difference. During this time we have granted over $985 million to support community projects across the country. In the last financial year we distributed more than $35 million to community-based organisations. We’re here to make a difference. Barnardos NZ “We can’t do the work we do without the help of generous supporters like The Lion Foundation.” – Dr Claire Achmad, General Manager Advocacy, Fundraising, Marketing & Communications THETHETHE LION LION LION FOUNDATION FOUNDATIONFOUNDATION | CHAIRMAN | CHAIRMAN AND AND CEO CEO REPORT REPORT Chairman and CEO Report CHAIRMAN’SCHAIRMAN’S REPORT REPORT CHIEFCHIEF EXECUTIVE’S EXECUTIVE’S REPORT REPORT Chairman’sThe LionThe FoundationLion Report Foundation has continued has continued its proud its proudthan inthan March in March 2020, 2020, when, when,as a nationas a nationwe weWhat anWhatChief interesting an interestingExecutive’s end to end our to2019/2020 our Report 2019/2020 financial financial year asyear as record of community fundraising over the past experienced a life changing pandemic. the Covid-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges I have had therecord privilege of community of writing thisfundraising message over to the the pastplatforms experienced disappear a lifeoverseas changing and pandemic.no resulting funding theWell, Covid-19 our 2020/21 pandemic financial presented year unprecedentedhas certainly beenchallenges an year, withyear, $38,296,847with $38,296,847 being beingdistributed distributed to Despiteto these unchartered times, The Lion - not only- not for only The for Lion The Foundation, Lion Foundation, our venue our venueoperators operators and and Lion Foundationsupport community forprojects several throughoutyears. -

East Coast Inquiry District: an Overview of Crown-Maori Relations 1840-1986

OFFICIAL Wai 900, A14 WAI 900 East Coast Inquiry District: An Overview of Crown- Maori Relations 1840-1986 A Scoping Report Commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal Wendy Hart November 2007 Contents Tables...................................................................................................................................................................5 Maps ....................................................................................................................................................................5 Images..................................................................................................................................................................5 Preface.................................................................................................................................................................6 The Author.......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................................ 6 Note regarding style........................................................................................................................................... 6 Abbreviations...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One: Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand

A supplementary finding-aid to the archives relating to Maori Schools held in the Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand MAORI SCHOOL RECORDS, 1879-1969 Archives New Zealand Auckland holds records relating to approximately 449 Maori Schools, which were transferred by the Department of Education. These schools cover the whole of New Zealand. In 1969 the Maori Schools were integrated into the State System. Since then some of the former Maori schools have transferred their records to Archives New Zealand Auckland. Building and Site Files (series 1001) For most schools we hold a Building and Site file. These usually give information on: • the acquisition of land, specifications for the school or teacher’s residence, sometimes a plan. • letters and petitions to the Education Department requesting a school, providing lists of families’ names and ages of children in the local community who would attend a school. (Sometimes the school was never built, or it was some years before the Department agreed to the establishment of a school in the area). The files may also contain other information such as: • initial Inspector’s reports on the pupils and the teacher, and standard of buildings and grounds; • correspondence from the teachers, Education Department and members of the school committee or community; • pre-1920 lists of students’ names may be included. There are no Building and Site files for Church/private Maori schools as those organisations usually erected, paid for and maintained the buildings themselves. Admission Registers (series 1004) provide details such as: - Name of pupil - Date enrolled - Date of birth - Name of parent or guardian - Address - Previous school attended - Years/classes attended - Last date of attendance - Next school or destination Attendance Returns (series 1001 and 1006) provide: - Name of pupil - Age in years and months - Sometimes number of days attended at time of Return Log Books (series 1003) Written by the Head Teacher/Sole Teacher this daily diary includes important events and various activities held at the school. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 467 405 RC 023 651 AUTHOR Moana, Whare Te; Selby, Rachael TITLE Monitoring a Maori Teacher Training Programme in Aotearoa New Zealand. PUB DATE 1999-07-00 NOTE 11p.; In: Indigenous Education around the World. Workshop Papers from the World Indigenous People's Conference: Education (Albuquerque, New Mexico, June 15-22, 1996); see RC 023 640. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biculturalism; *Culturally Relevant Education; *Educational Innovation; Extension Education; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Indigenous Personnel; Indigenous Populations; Language Maintenance; *Maori (People); *Preservice Teacher Education; Program Descriptions; Rural Education; School Community Relationship; *Teacher Education Programs IDENTIFIERS New Zealand; *Program Monitoring ABSTRACT For years, Maori tribes have wanted their own people to be trained as teachers and to return to teach their own language and culture in their tribal regions. Many Maori who returned from colleges of education had absorbed too much of European New Zealanders' ways and did not meet their community's expectations. Maori-education preschools were graduating 5-year- olds who were bilingual, Maori-English speakers, but Maori parents and communities became increasingly concerned that state primary-school teachers were unprepared to continue or maintain these students' Maori language development. Maori communities challenged the educational system to become more sensitive to -

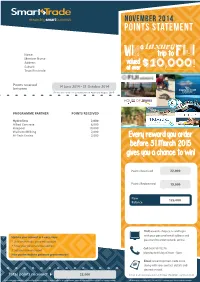

Points Statement

STstatement.pdf 7 10/11/14 2:27 pm NOVEMBER 2014 POINTS STATEMENT a luxury Name win trip to Fiji Member Name Address valued $10 000 Suburb at over , ! Town/Postcode Points received 14 June 2014 - 31 October 2014 between (Points allocated for spend between April and August 2014) FIJI’S CRUISE LINE PROGRAMME PARTNER POINTS RECEIVED Hydroflow 2,000 Allied Concrete 6,000 Hirepool 10,000 Waikato Milking 2,000 Hi-Tech Enviro 2,000 Every reward you order before 31 March 2015 gives you a chance to win! Points Received 22,000 Points Redeemed 15,000 New 125,000 Balance Visit rewards-shop.co.nz and login with your personal email address and Update your account in 3 easy steps: password to order rewards online. 1. Visit smart-trade .co.nz/my-account 2. Enter your personal email address Call 0800 99 76278 3. Set your new password Monday to Friday 8:30am - 5pm. Now you’re ready to get more great rewards! Email [email protected] along with your contact details and desired reward. * Total points received 22,000 Smart Trade International Ltd, PO Box 370, WMC, Hamilton 3240 *If your total points received does not add up, it may be a result of a reward cash top up, points transfer or manual points issue. Please call us if you have any queries. All information is correct as at 31 October 2014. Conditions apply. Go online for more details. GIVE YOUR POINTS A BOOST! Over 300 businesses offering Smart-Trade reward points. To earn points from any of the companies listed below, contact the business, express your desire to earn points and discuss opening an account. -

2018: New Zealand's Equal-2Nd Warmest Year on Record

New Zealand Climate Summary: 2018 Issued: 8 January 2019 2018: New Zealand’s equal-2nd warmest year on record Temperature Annual temperatures were above average (+0.51°C to +1.20°C above the annual average) across the majority of New Zealand, including much of the North Island as well as the western and southern South Island. A small strip of well above average (>1.20°C from average) temperatures were observed in southern Manawatu-Whanganui. Elsewhere, near average (within -0.50°C to +0.50°C of average) temperatures occurred in parts of southern Canterbury, Otago, small parts of Auckland and the Far North. 2018 was the equal 2nd-warmest year on record for New Zealand, based on NIWA’s seven- station series which began in 1909. Rainfall Yearly rainfall in 2018 was above normal (120-149% of the annual normal) across much of the eastern and upper South Island, as well as parts of Wellington, Wairarapa, Bay of Plenty, northern Waikato, and Auckland. Well above normal rainfall (>149% of normal) was observed in portions of southern Canterbury. Rainfall was near normal (80-119% of normal) for the remainder of New Zealand. Soil moisture 2018 began with below or well below normal soil moisture nearly nationwide, but soil moisture in the North Island and upper South Island gradually increased during January. Widespread heavy rainfall from ex-tropical cyclones Fehi and Gita during February resulted in well above normal soil moisture across most of New Zealand. Near to above normal soil moisture persisted through autumn, with near normal soil moisture widespread during the winter. -

A Critical Examination of Māori Economic Development: a Ngāti Awa Perspective’

A Critical Examination of Māori Economic Development: A Ngāti Awa Perspective James Daniel Mather PhD 2014 ‘A Critical Examination of Māori Economic Development: A Ngāti Awa Perspective’ A Critical Examination of Māori Economic Development: A Ngāti Awa Perspective James Daniel Mather A thesis submitted to the Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2014 Department of Economics Page 2 of 300 ‘A Critical Examination of Māori Economic Development: A Ngāti Awa Perspective’ ABSTRACT This thesis provides a critical examination of Māori economic development with particular emphasis on the Eastern Bay of Plenty iwi of Ngāti Awa. A ‘development patterns framework’ was employed in order to explore key patterns and characteristics associated with Ngāti Awa development from the arrival of Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand, the subsequent colonisation by Britain, and the outcome of these two very different settlement patterns. The preliminary sections of the thesis discuss the relevant social, cultural, political and economic contexts that are used to build the multi-layered historical foundation of the research. The underlying evidential base includes a comprehensive literature review of historical records such as examination of the Ngāti Awa Treaty of Waitangi claim, as well as a comparative analysis of alternative indigenous development models in both non-tribal and international contexts. The research approach was designed with two aims: Firstly, to clarify what is meant by ‘Maori Economic Development’ – an approach that allows the researcher to refine both its meaning and practical application. And secondly, to provide the foundation for the field research and to elicit key findings from a series of interviews conducted with ‘key informants’. -

Eight Existing Poverty Initiatives in NZ and the UK: a Compilation

Title page July 2017 Working Paper 2017/04 Eight Existing Poverty Initiatives in NZ and the UK: A compilation Working Paper 2017/04 Fact Sheets on Existing Initiatives: A compliation July 2017 Title Working Paper 2017/04 – Eight Existing Poverty Initiatives in NZ and the UK: A compilation Published Copyright © McGuinness Institute, July 2017 ISBN 978-1-98-851842-8 (Paperback) ISBN 978-1-98-851843-5 (PDF) This document is available at www.mcguinnessinstitute.org and may be reproduced or cited provided the source is acknowledged. Prepared by The McGuinness Institute, as part of the TacklingPovertyNZ project. Authors Alexander Jones and Ali Bunge Research team Ella Reilly and Eleanor Merton For further information McGuinness Institute Phone (04) 499 8888 Level 2, 5 Cable Street PO Box 24222 Wellington 6142 New Zealand www.mcguinnessinstitute.org Disclaimer The McGuinness Institute has taken reasonable care in collecting and presenting the information provided in this publication. However, the Institute makes no representation or endorsement that this resource will be relevant or appropriate for its readers’ purposes and does not guarantee the accuracy of the information at any particular time for any particular purpose. The Institute is not liable for any adverse consequences, whether they be direct or indirect, arising from reliance on the content of this publication. Where this publication contains links to any website or other source, such links are provided solely for information purposes and the Institute is not liable for the content of any such website or other source. Publishing This publication has been produced by companies applying sustainable practices within their businesses. -

Health Literacy in Palliative Care

Kia Mau te Kahu Whakamauru: Health Literacy in Palliative Care June 2014 Dr Jacquie Kidd Susan Reid Nicola Collins Dr Veronique Gibbons Stella Black Rawiri Blundell Tamati Peni Matua Hone Ahu Te puāwaitanga o te hinengaro mō te tangata He Mihimihi He hōnore, he korōria ki te Atua He maungarongo ki te whenua He whakaaro pai ki ngā tāngata katoa Tēnā rā koutou, e te iwi nui tonu, ka whakakorōria tonu i te Atua Kaha Rawa. Kia tau tonu ōna manaakitanga maha ki runga i Te Arikinui Kīngi Tūheitia, me te Whare o te Kāhui Ariki. Kua tangihia kēngia, ngā mate o te wā! Nō reira, rātou ki a rātou! Tātou, kē, o te ao mōrehu, ki a tātou! Ka kitea i raro nei, he kaupapa whakahirahira, ka pā ki ngā tāngata kua tino pāngia e ngā momo mate pukupuku, me ngā tūroro, kua tata whakawhiti atu ki tua o te ārai. Anō hoki, o rātou whānau e mōhio pai ana ki ngā āhuatanga whai pānga ki te manaaki pai i te tūroro. E mihi ana ki ngā whānau kua uiuingia mō te taha rangahau o te kaupapa me rātou ngā kaimahi o te ratonga mō ngā tūroro kua tata te whakawhiti ki tua o te ārai. Mā te Runga Rawa e tiaki, e manaaki tonu i a koutou; ahakoa te aha! This report was written by Dr Jacquie Kidd (University of Auckland); Susan Reid (Workbase Education Trust); Nicola Collins (UniServices), Stella Black (University of Auckland), Dr Veronique Gibbons (University of Auckland); Rawiri Blundell (Midlands Cancer Network); Tamati Peni (University of Waikato) and Matua Hone Ahu (Tainui). -

Very Wet in Many Parts and an Extremely Cold Snap for the South

New Zealand Climate Summary: June 2015 Issued: 3 July 2015 Very wet in many parts and an extremely cold snap for the south. Rainfall Rainfall was above normal (120-149%) or well above normal (> 149%) for much of the Manawatu-Whanganui, Taranaki, Westland, Tasman, Nelson, Marlborough, Canterbury, Otago, and Southland regions. Rainfall was well below normal (< 50%) or below normal (50-79%) for parts of Northland, Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay, and north Canterbury. Temperature June temperatures were near average across much of the country (within 0.5°C of June average). Below average temperatures were recorded in inland Canterbury, Wairarapa, western Waikato (0.5-1.2°C below June average) and above average temperatures experienced in northern, eastern, and western parts of the North Island and northern, western, and south-central parts of the South Island (0.5-1.2°C above June average). A polar outbreak in late June led to the 4th-lowest temperature ever recorded in New Zealand. Soil Moisture As of 1 July 2015, soil moisture levels were below normal for this time of year for East Cape, around and inland from Napier, coastal Wairarapa, coastal southern Marlborough and eastern parts of Canterbury north of Christchurch. It was especially dry about north Canterbury where soils were considerably drier than normal for this time of year. Sunshine Well above normal (>125%) or above normal (110-125%) sunshine was recorded in Northland, Auckland, western Waikato, Wellington, Marlborough, north Canterbury, and Central Otago. Near normal sunshine (within 10% of normal) was recorded elsewhere, expect in Franz Josef and Tauranga where below normal sunshine was recorded. -

Archaeology of the Bay of Plenty

Figure A3.1. Distribution of C14 dated sites (sites in the Recording Scheme only) in the Bay of Plenty region. The presence of human bone in the materials does not represent modern archaeological practice. The samples reported here as containing this were all submitted by people other than archaeologists for forensic identification purposes. The distribution of dated material naturally closely follows the excavated sites plot, but illustrates a concentration around Tauranga/Papamoa, where samples collected from mitigation excavations have frequently been dated. 131 TABL E A3.2. CARBON 14 DATES LISTED IN THE NEW ZEALAND RADIOCARBON DATABASE. This table of dates was sourced from the New Zealand Radiocarbon Database (http://waikato.ac.nz/nzcd/index.html; viewed June 2008). More information on the dates can be found at that source. CRA is the conventional radiocarbon age in years. Note: dates in this table are presented without the reservoir correction that is routinely applied to shell and other marine-sourced sample ages; dates with reservoir correction are more commonly found in archaeological publications. LAB NO. CRA ± MATERIAL SITE SITE CONTEXT ERROR NUMBEr namE ANU0025 495 ± 78 Charcoal (unspecified) U13/4 Kauri Point Pa Sample from the first modified terrace on the pa. ANU0026 230 ± 70 Charcoal (unspecified) U13/4 Kauri Point Pa Square L29–30. Sample from a depression in the floor of the pit. ANU0046 395 ± 53 Charcoal (unspecified) U13/4 Kauri Point Pa Second shell midden, younger than the first defensive ditch. NZ0592 404 ± 59 Wood (unspecified) U13/4 Kauri Point Swamp Sample from the base of the archaeological deposit. -

Komiti Māori

Komiti Māori NOTICE IS GIVEN that the next meeting of Komiti Māori will be held at Wairuru Marae, 9860 State Highway 35, Raukōkore, Waihau Bay on: Tuesday, 11 June 2019 commencing at 9.30 am Please note: A pōhiri/welcome will take place at 9.30 am with the meeting to start at approximately 10.30 am. Fiona McTavish Chief Executive 30 May 2019 Komiti Māori Terms of Reference The Komiti Māori has the core function of implementing and monitoring Council’s legislative obligations to Māori. Delegated Function To set operational direction for Council’s legislative obligations to Māori and monitor how these obligations are implemented. This will be achieved through the development of specific operational decisions which translate legislative obligations to Māori into action. Membership Three Māori constituency councillors and three general constituency councillors (the membership of the general constituency councillors to be rotated every two years), and the Chairman as ex-officio. Quorum In accordance with Council standing order 10.2, the quorum at a meeting of the committee is not fewer than three members of the committee. Co-Chairs to preside at meetings Notwithstanding the Komiti Māori has an appointed Chairperson, Māori Constituency Councillors may host-Chair committee meetings that are held in the rohe of their respective constituency. Term of the Committee For the period of the 2016-2019 Triennium unless discharged earlier by the Regional Council. Meeting frequency Two-monthly. Specific Responsibilities and Delegated Authority The Komiti