Informed Trading in Government Bond Markets*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informed and Strategic Order Flow in the Bond Markets

Informed and Strategic Order Flow in the Bond Markets Paolo Pasquariello Ross School of Business, University of Michigan Clara Vega Simon School of Business, University of Rochester and FRBG We study the role played by private and public information in the process of price formation in the U.S. Treasury bond market. To guide our analysis, we develop a parsimonious model of speculative trading in the presence of two realistic market frictions—information heterogeneity and imperfect competition among informed traders—and a public signal. We test its equilibrium implications by analyzing the response of two-year, five-year, and ten-year U.S. bond yields to order flow and real-time U.S. macroeconomic news. We find strong evidence of informational effects in the U.S. Treasury bond market: unanticipated order flow has a significant and permanent impact on daily bond yield changes during both announcement and nonannouncement days. Our analysis further shows that, consistent with our stylized model, the contemporaneous correlation between order flow and yield changes is higher when the dispersion of beliefs among market participants is high and public announcements are noisy. (JEL E44, G14) Identifying the causes of daily asset price movements remains a puzzling issue in finance. In a frictionless market, asset prices should immediately adjust to public news surprises. Hence, we should observe price jumps only during announcement times. However, asset prices fluctuate significantly during nonannouncement days as well. This fact has motivated the introduction of various market frictions to better explain the behavior The authors are affiliated with the Department of Finance at the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan (Pasquariello) and the University of Rochester, Simon School of Business and the Federal Reserve Board of Governors (Vega). -

Government Bonds Have Given Us So Much a Roadmap For

GOVERNMENT QUARTERLY LETTER 2Q 2020 BONDS HAVE GIVEN US SO MUCH Do they have anything left to give? Ben Inker | Pages 1-8 A ROADMAP FOR NAVIGATING TODAY’S LOW INTEREST RATES Matt Kadnar | Pages 9-16 2Q 2020 GOVERNMENT QUARTERLY LETTER 2Q 2020 BONDS HAVE GIVEN US SO MUCH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Do they have anything left to give? The recent fall in cash and bond yields for those developed countries that still had Ben Inker | Head of Asset Allocation positive yields has left government bonds in a position where they cannot provide two of the basic investment services they When I was a student studying finance, I was taught that government bonds served have traditionally provided in portfolios – two basic functions in investment portfolios. They were there to generate income and 1 meaningful income and a hedge against provide a hedge in the event of a depression-like event. For the first 20 years or so an economic disaster. This leaves almost of my career, they did exactly that. While other fixed income instruments may have all investment portfolios with both a provided even more income, government bonds gave higher income than equities lower expected return and more risk in the and generated strong capital gains at those times when economically risky assets event of a depression-like event than they fell. For the last 10 years or so, the issue of their income became iffier. In the U.S., the used to have. There is no obvious simple income from a 10-Year Treasury Note spent the last decade bouncing around levels replacement for government bonds that similar to dividend yields from equities, and in most of the rest of the developed world provides those valuable investment government bond yields fell well below equity dividend yields. -

Chapter 7 Interest Rates and Bond Valuation

Chapter 7 When corp. need to investment in new plant and equipment, it required money. So’ corp. need to raise cash / funds. Interest Rates and • Borrow the cash from bank (or Issue bond Bond Valuation / debt securities) (CHP. 7) • Issue new securities (i.e. sell additional shares of common stock) (CHP. 8) 7-0 7-1 Differences Between Debt and Chapter Outline Equity • Debt • Equity • Bonds and Bond Valuation • Not an ownership • Ownership interest interest • Common stockholders vote • Bond Ratings and Some Different Types of • Creditors do not have for the board of directors and other issues voting rights Bonds • Dividends are not • Interest is considered a considered a cost of doing • The Fisher Effect – the relationship cost of doing business business and are not tax and is tax deductible deductible between inflation, nominal interest rates • Creditors have legal • Dividends are not a liability and real interest rates remedy if interest or of the firm and stockholders have no legal remedy if principal payments are dividends are not paid missed • An all equity firm can not go • Excess debt can lead to bankrupt financial distress and bankruptcy 7-2 7-3 BOND • When corp. (or gov.) wishes • In return, they promise to pay to borrow money from the series of fixed interest payments public on a L-T basis, it and then to repay the debt to the usually does so by issuing or bondholders (lenders). selling debt securities that • Par value is usually $1000 are generally called BOND. for corporate bond 7-4 7-5 Bond • Par value (face value) • Face Value (Par Value): The principal • Coupon rate amount of a bond that will be repaid at • Coupon payment the end of the loan. -

Secondary Market Trading Infrastructure of Government Securities

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Balogh, Csaba; Kóczán, Gergely Working Paper Secondary market trading infrastructure of government securities MNB Occasional Papers, No. 74 Provided in Cooperation with: Magyar Nemzeti Bank, The Central Bank of Hungary, Budapest Suggested Citation: Balogh, Csaba; Kóczán, Gergely (2009) : Secondary market trading infrastructure of government securities, MNB Occasional Papers, No. 74, Magyar Nemzeti Bank, Budapest This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/83554 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu MNB Occasional Papers 74. 2009 CSABA BALOGH–GERGELY KÓCZÁN Secondary market trading infrastructure of government securities Secondary market trading infrastructure of government securities June 2009 The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official view of the central bank of Hungary (Magyar Nemzeti Bank). -

Corporate Bonds

UNDERSTANDING INVESTING Corporate Bonds After government bonds, the corporate bond market is the largest section of the global bond universe. With a vast array of maturities, yields and credit quality available, investing in corporate bonds has the potential to provide higher yields than government bonds and diversification benefits for investors. WHAT ARE CORPORATE BONDS? Speculative-grade bonds are issued by companies perceived to have a lower level of credit quality compared to more highly When companies want to expand operations or fund new rated, investment-grade, companies. The investment-grade business ventures, they often turn to the corporate bond category has four rating grades while the speculative-grade market to borrow money. A company determines how much category is comprised of six rating grades. it would like to borrow and then issues a bond offering in that amount; investors that buy a bond are effectively lending money to the company according to the terms established in STANDARD MOODY’S & POORS the bond offering or prospectus. INVESTMENT GRADE Unlike equities, ownership of corporate bonds does not signify an ownership interest in the company that has issued the Highest quality (Best quality, smallest degree of Aaa AAA bond. Instead, the company pays the investor a rate of interest investment risk) over a period of time and repays the principal at the maturity High Quality Aa AA date established at the time of the bond’s issue. (Often called high-grade bonds) While some corporate bonds have redemption or call features -

Speculation in the United States Government Securities Market

Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 2/25/2020 Se t m e 1, 958 p e b r 1 1 To Members of the Federal Open Market Committee and Presidents of Federal Reserve Banks not presently serving on the Federal Open Market Committee From R. G. Rouse, Manager, System Open Market Account Attached for your information is a copy of a confidential memorandum we have prepared at this Bank on speculation in the United States Government securities market. Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 2/25/2020 C O N F I D E N T I AL -- (F.R.) SPECULATION IN THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT SECURITIES MARKET 1957 - 1958* MARKET DEVELOPMENTS Starting late in 1957 and carrying through the middle of August 1958, the United States Government securities market was subjected to a vast amount of speculative buying and liquidation. This speculation was damaging to mar- ket confidence,to the Treasury's debt management operations, and to the Federal Reserve System's open market operations. The experience warrants close scrutiny by all interested parties with a view to developing means of preventing recurrences. The following history of market events is presented in some detail to show fully the significance and continuous effects of the situation as it unfolded. With the decline in business activity and the emergence of easier Federal Reserve credit and monetary policy in October and November 1957, most market elements expected lower interest rates and higher prices for United States Government securities. There was a rapid market adjustment to these expectations. -

The Innovation of Government Bonds in the Growth of an Emergent Capital Market

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity Article The Innovation of Government Bonds in the Growth of an Emergent Capital Market Cordelia Onyinyechi Omodero 1,* and Philip Olasupo Alege 2 1 Department of Accounting, College of Management and Social Sciences, Covenant University, Ota 110001, Ogun State, Nigeria 2 Department of Economics and Development Studies, College of Management and Social Sciences, Covenant University, Ota 110001, Ogun State, Nigeria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The growth of an emerging capital market is necessary and requires all available resources and inputs from various sources to realize this objective. Several debates on government bonds’ contribution to Nigeria’s capital market developmental growth have ensued but have not triggered comprehensive studies in this area. The present research work seeks to close the breach by probing the impact of government bonds on developing the capital market in Nigeria from 2003–2019. We employ total market capitalization as the response variable to proxy the capital market, while various government bonds serve as the independent variables. The inflation rate moderates the predictor components. The research uses multiple regression technique to assess the explanatory variables’ impact on the total market capitalization. At the same time, diagnostic tests help guarantee the normality of the regression model’s data distribution and appropriateness. The findings reveal that the Federal Government of Nigeria’s (FGN) bond is statistically significant and positive in influencing Nigeria’s capital market growth. The other predictor variables are not found significant in this study. The study suggests that the Government should improve on the government bonds’ coupon, while still upholding the none default norm in paying interest and refunding principal to investors when due. -

Chapter 10 Bond Prices and Yields Questions and Problems

CHAPTER 10 Bond Prices and Yields Interest rates go up and bond prices go down. But which bonds go up the most and which go up the least? Interest rates go down and bond prices go up. But which bonds go down the most and which go down the least? For bond portfolio managers, these are very important questions about interest rate risk. An understanding of interest rate risk rests on an understanding of the relationship between bond prices and yields In the preceding chapter on interest rates, we introduced the subject of bond yields. As we promised there, we now return to this subject and discuss bond prices and yields in some detail. We first describe how bond yields are determined and how they are interpreted. We then go on to examine what happens to bond prices as yields change. Finally, once we have a good understanding of the relation between bond prices and yields, we examine some of the fundamental tools of bond risk analysis used by fixed-income portfolio managers. 10.1 Bond Basics A bond essentially is a security that offers the investor a series of fixed interest payments during its life, along with a fixed payment of principal when it matures. So long as the bond issuer does not default, the schedule of payments does not change. When originally issued, bonds normally have maturities ranging from 2 years to 30 years, but bonds with maturities of 50 or 100 years also exist. Bonds issued with maturities of less than 10 years are usually called notes. -

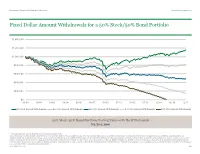

Fixed Dollar Amount Withdrawals for a 50% Stock/50% Bond Portfolio

Independent Perspective | Real-World Solutions www.manning-napier.com Fixed Dollar Amount Withdrawals for a 50% Stock/50% Bond Portfolio $1,400,000 $1,200,000 $1,000,000 $800,000 $600,000 $400,000 $200,000 $0 03/00 09/01 03/03 08/04 02/06 08/07 01/09 07/10 01/12 07/13 12/14 06/16 12/17 $40,000 Annual Withdrawals $50,000 Annual Withdrawals $60,000 Annual Withdrawals $70,000 Annual Withdrawals $80,000 Annual Withdrawals 50% Stock/50% Bond Portfolio Ending Value with No Withdrawals $2,504,990 For illustrative purposes only. Past performance does not guarantee future returns. Source: Morningstar. The 50% Stock/50% Bond Portfolio is reflected by 50% Ibbotson Associates SBBI U.S. Large Stock Index and 50% Ibbotson Associates SBBI U.S. Intermediate-Term Government Bond Index. The Ibbotson Associates SBBI U.S. Large Stock Index is an unmanaged index representing the broad U.S. large cap stock market. The Ibbotson Associates SBBI U.S. Intermediate-Term Government Bond Index is an unmanaged index representing the U.S. intermediate-term government bond market. The index is constructed as a one bond portfolio consisting of the shortest-term non callable government bond with less than 5 years to maturity. The Index returns do not reflect any fees or expenses. ©2018 Morningstar, Inc. All rights reserved. The information contained herein: (1) is proprietary to Morningstar and/or its content providers; (2) may not be copied, adapted or distributed; and (3) is not warranted to be accurate, complete or timely. -

China's Sovereign Bonds

Brandywine Global Investment Management, LLC Topical Insight | April 22, 2021 China’s Sovereign Bonds The Alternative Safe Haven OVERVIEW Against a dreary backdrop of low, zero, or negative yields from traditionally safe-haven bonds like U.S. Treasuries, China’s sovereign bonds offer an alternative way to diversify a global portfolio. By combining higher yields, relative to developed market bonds, and lower volatility, relative to emerging market bonds, Chinese sovereign bonds have produced high risk-adjusted returns with low correlations over the past 10 years. Within a global framework, we believe China’s government bonds now compare more closely to developed markets (DM) than to emerging markets (EM). However, there are several major trends impacting the world’s largest developed bond markets and reducing their ability to hedge portfolios during risk-off periods. We review these trends and demonstrate how their impact on China may differ. We also discuss how the opening of China’s onshore market equates to a “Big Bang” event in global fixed income, on par with China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO). Faced with the structural decline of its current account surplus, China needs more foreign capital to fund its future growth, upgrade its manufacturing value chain, and promote its currency globally. As China seeks to pivot away from an export-driven economy, its more welcoming stance could benefit foreign investors in its onshore bond market. Lastly, we examine the information and price risks to our China safe-haven investment thesis. On the back of China’s strong post-pandemic, V-shaped recovery, we expect growth momentum will taper off later in 2021 as policymakers return to the delicate process of deleveraging financial risks and asset bubbles while avoiding a policy cliff. -

The Development of the Domestic Government Bond Market in Mexico1

Serge Jeanneau Carlos Pérez Verdia +52 55 9138 0294 +52 55 5227 8840 [email protected] [email protected] Reducing financial vulnerability: the development of the domestic government bond market in Mexico1 There is broad evidence that various initiatives undertaken by the Mexican government have been successful in helping to develop the domestic government bond market. The market has grown rapidly, its maturity structure has lengthened and secondary market liquidity has improved. Primary market auctions have also become more efficient. Notwithstanding these significant advances, some vulnerabilities remain. JEL classification: E440, G180, H630, O160. The domestic government bond market has expanded rapidly in Mexico since the mid-1990s. In part, this has reflected a conscious effort by the authorities to develop domestic sources of financing as a means of reducing the country’s dependence on external capital flows. The abrupt withdrawal of external capital in late 1994, in what became widely known as the “tequila crisis”, resulted in a deep economic and financial crisis in Mexico. This made policymakers acutely aware of the vulnerabilities associated with a heavy reliance on external financing. The Mexican government has promoted the shift to financing in the domestic market through macroeconomic and structural reforms aimed at strengthening the demand for domestic debt, as well as through the introduction of a clearly defined debt management strategy. These measures have been broadly successful: the government has been able to issue a growing amount of domestic fixed rate securities and to create a long-term yield curve. These are notable developments in a region where short-term or indexed debt remains the rule. -

City National Rochdale Government Bond Fund a Series of City National Rochdale Funds

City National Rochdale Government Bond Fund a series of City National Rochdale Funds SUMMARY PROSPECTUS DATED JANUARY 31, 2021 Class: Ticker: Servicing Class (CNBIX) Class N (CGBAX) Before you invest, you may want to review the Fund’s Prospectus, which contains more information about the Fund and its risks. You can find the Fund’s Prospectus and other information about the Fund, including the Fund’s Statement of Additional Information and shareholder reports, online at http://www.citynationalrochdalefunds.com. You can also get this information at no cost by calling (888) 889-0799 or by sending an e-mail request to [email protected] or from your financial intermediary. The Fund’s Prospectus and Statement of Additional Information, dated January 31, 2021, as may be amended or further supplemented, and the independent registered public accounting firm’s report and financial statements in the Fund’s Annual Report to shareholders, dated September 30, 2020, are incorporated by reference into this Summary Prospectus. City National Rochdale Government Bond Fund INVESTMENT GOAL The City National Rochdale Government Bond Fund (the “Government Bond Fund” or the “Fund”) seeks to provide current income (as the primary component of a total return intermediate duration strategy) by investing primarily in U.S. Government securities. FEES AND EXPENSES OF THE FUND The table below describes the fees and expenses you may pay if you buy, hold, and sell shares of the Government Bond Fund. You may pay other fees, such as brokerage commissions and other fees to financial intermediaries, which are not reflected in the table and example below.