Southeastern Theological Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7

Chapter 20 4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7 Gaye Strathearn am personally grateful for S. Kent Brown. He was a commit- I tee member for my master’s thesis, in which I examined 4Q521. Since that time he has been a wonderful colleague who has always encouraged me in my academic pursuits. The relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian- ity has fueled the imagination of both scholar and layperson since their discovery in 1947. Were the early Christians aware of the com- munity at Qumran and their texts? Did these groups interact in any way? Was the Qumran community the source for nascent Chris- tianity, as some popular and scholarly sources have intimated,¹ or was it simply a parallel community? One Qumran fragment that 1. For an example from the popular press, see Richard N. Ostling, “Is Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls?” Time Magazine, 21 September 1992, 56–57. See also the claim that the scrolls are “the earliest Christian records” in the popular novel by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 245. For examples from the academic arena, see André Dupont-Sommer, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Preliminary Survey (New York: Mac- millan, 1952), 98–100; Robert Eisenman, James the Just in the Habakkuk Pesher (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 1–20; Barbara E. Thiering, The Gospels and Qumran: A New Hypothesis (Syd- ney: Theological Explorations, 1981), 3–11; Carsten P. Thiede, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 152–81; José O’Callaghan, “Papiros neotestamentarios en la cueva 7 de Qumrān?,” Biblica 53/1 (1972): 91–100. -

The Book of Joel

Charles Savelle Center Point Bible Institute 1 THE BOOK OF JOEL Message: The message to Joel is fairly straightforward. Basically, it is that, “The Day of the Lord is coming to bring judgment for God’s enemies and restoration for God’s people.” Joel sets his message up by pointing to a literal locust plague which he poetically morphs into a eschatological Day of the Lord. Or as Finley puts it, “The prophecy of Joel can be compared to two wheels turning on an axle. The wheels are history and eschatology, while the axle is the day of the Lord.”1 Author: According to 1:1, the human author of the prophecy was Joel son of Pethuel. Joel means “Yahweh is God.” The name was fairly popular and there are eleven to fourteen men who bear this designation in the Old Testament depending on how you count them. The references to “Zion” and “the house of the Lord” (1:9, 13–14; 2:15–17, 23, 32; 3:1, 5–6, 16–17, 20–21) might indicate that the prophet was a resident of Jerusalem. References to the priesthood (1:13–14; 2:17) might indicate that Joel was a priest. Nothing is known about his father Pethual. Recipients: The identification of the original recipients is tied closely to the issue of dating. While most would hold that the oracle was written to Judah, dating affects whether we are referring to pre-exilic or exilic Judah. Since an early date seems more likely, the original recipients are likely pre-exilic Israel. -

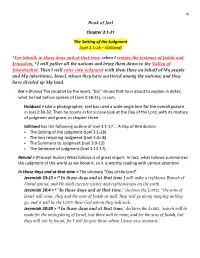

Book of Joel Chapter 3:1-21 the Setting of the Judgment (Joel 3:1

(1) Book of Joel Chapter 3:1-21 The Setting of the Judgment (Joel 3:1-2b – Gilliland) 1 For behold, in those days and at that time, when I restore the fortunes of Judah and Jerusalem, 2 I will gather all the nations and bring them down to the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Then I will enter into judgment with them there on behalf of My people and My inheritance, Israel, whom they have scattered among the nations; and they have divided up My land. For > (Pusey) The prophet by the word, "for," shows that he is about to explain in detail, what he had before spoken of (Joel 2:18-31), in sum. Hubbard > Like a photographer, Joel has used a wide-angle lens for the overall picture in Joel 2:30-32. Then he zooms in for a close look at the Day of the Lord, with its mixture of judgment and grace, in chapter three Gilliland has the following outline of Joel 3:1-17 … A Day of Retribution . The Setting of the Judgment (Joel 3:1-2b) . The Sins requiring Judgment (Joel 3:2c-8) . The Summons to Judgment (Joel 3:9-12) . The Sentence of Judgment (Joel 3:13-17). Behold > (Precept Austin) What follows is of great import. In fact, what follows summarizes the judgment of the world as we know it, so it is worthy reading with utmost attention. In those days and at that time > The ultimate “Day of the Lord” Jeremiah 33:15 > 15 In those days and at that time I will make a righteous Branch of David sprout; and He shall execute justice and righteousness on the earth. -

Torah Toons One Sample

1. Bereshit Genesis 1:1-6:8 At the beginning of God’s creating of the heavens and the earth (Genesis 1:1). [1] BERESHIT starts things. God creates the world. This is done in seven days. On the first day, light is created. On the second day, there is a division of the waters. On the third day, dry land appears and plants begin to grow. On the fourth day, God creates the things which give light—the sun, moon and stars. On the fifth day, birds and fish are created. And, on the sixth day, God creates animals and people. On the seventh day, God rests. [2] Next, the sidrah tells the story of what happens in the Garden of Eden. The garden is described, and Adam then Havva are created. The garden has two trees in its center—the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowing Good from Evil. Havva and Adam are told not to eat from the trees in the center, but do so at the urging of the snake. God then sends Adam and Havva from the garden. Two angels guard the entrance. 5 [3] Once outside the garden, Adam and Havva have two sons: Kayin and Hevel. Kayin is a farmer and Hevel is a shepherd. Both offer sacrifices to God, but God accepts only Hevel’s offering. The two then fight and Kayin kills Hevel. God then marks Kayin, who heads off into the sunset. [4] The sidrah ends with a list of the ten generations from Adam to Noah. At the end of the list the Torah gives us a preview of COMING ATTRACTIONS: Tune in next week for the Flood. -

Strategies –Modern Midrash

Chapter Nine – Modern Midrash: Movies, Art, Poetry, Literature, Popular Songs #1 - Film as Midrash East of Eden – a novel by John Steinbeck and a movie by Elia Kazan starring Jimmy Dean p. 2 The Prince of Egypt – film by Spielberg p. 22 David and Batsheba starring Gregory Peck and Susan Hayward (1951) p. 25 #2 - Art as Parshanut: p. 36 A Systematic Analysis of Art as Commentary Sample – David and Avigail #3 - Novels and Bible: p. 44 Political Midrash by Stefan Heym on David and Batsheva #4 - Contemporary Poetry and Song as Midrash p. 53 "Adam Raised a Cain" by "The King" Bruce Springsteen "Hide and Seek" by Dan Pagis on Avram "David's Wives" by Yehuda Amichai #5 - Handmade Midrash: Jo Milgrom p. 70 1 #1 - Film as Midrash East of Eden – a novel by John Steinbeck and a movie by Elia Kazan starring Jimmy Dean Advice to the Educator for Analyzing a Movie as a Midrash A Generative Topic Teaching a movie is a large commitment of time and its proper introduction takes even longer and for the movie to be seen as a midrash the Biblical text must have been analyzed in depth with a eye to its gaps. However this is power exercise that achieves many goals: close text analysis; philosophic – psychological- theological exploration of major issues of sibling rivalry, free will and Divine justice; creative contemporary reverberations of the Biblical story that might otherwise be seen as merely Jewish and merely ancient and merely verbal; an alternative medium – a movie that models the principles of midrash and invites students to continue creating in that tradition; modeling close reading of movie etc. -

JANUARY 3, 2016 the Epiphany of the Lord

JANUARY 3, 2016 The Epiphany of the Lord READING 1 IS 60:1-6 RESPONSORIAL PSALM PS 72:1-2, 7-8, 10-11, 12-13. R. (cf. 11) Lord, every nation on earth will adore you. READING 2 EPH 3:2-3A, 5-6 GOSPEL MT 2:1-12 When Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, and ascertained from them the time of the star's in the days of King Herod, appearance. behold, magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem, He sent them to Bethlehem and said, saying, "Go and search diligently for the child. "Where is the newborn king of the Jews? When you have found him, bring me word, We saw his star at its rising that I too may go and do him homage." and have come to do him homage." After their audience with the king they set out. When King Herod heard this, And behold, the star that they had seen at its rising he was greatly troubled, preceded them, and all Jerusalem with him. until it came and stopped over the place where the Assembling all the chief priests and the scribes of child was. the people, They were overjoyed at seeing the star, He inquired of them where the Christ was to be and on entering the house born. they saw the child with Mary his mother. They said to him, "In Bethlehem of Judea, They prostrated themselves and did him homage. for thus it has been written through the prophet: Then they opened their treasures And you, Bethlehem, land of Judah, and offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; myrrh. -

The Shema in John's Gospel Against Its Backgrounds in Second Temple

The Shema in John’s Gospel Against its Backgrounds in Second Temple Judaism by Lori Ann Robinson Baron Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date: Approved: ___________________________ Joel Marcus, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Goodacre ___________________________ Richard B. Hays ___________________________ Laura S. Lieber Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT The Shema in John’s Gospel Against its Backgrounds in Second Temple Judaism by Lori Ann Robinson Baron Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date: Approved: ___________________________ Joel Marcus, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Goodacre ___________________________ Richard B. Hays ___________________________ Laura S. Lieber An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Lori Ann Robinson Baron 2015 Abstract In John’s Gospel, Jesus does not cite the Shema as the greatest commandment in the Law as he does in the Synoptic Gospels (“Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might” [Deut 6:4-5]; only Deut 6:5 appears in Matthew and Luke). This dissertation, however, argues that, rather than quoting the Shema , John incorporates it into his Christological portrait of Jesus’ unity with the Father and of the disciples’ unity with the Father, the Son, and one another. This study employs historical-critical methodology and literary analysis to provide an exegetical interpretation of the key passages relevant to the Shema in John (John 5:1-47; 8:31-59; 10:1-42; 13:34; 14, 15, 17). -

This Complimentary Copy of the Book of Joel Is from the CEB Study Bible, a Recommended Resource for Covenant Bible Study

This complimentary copy of the book of Joel is from The CEB Study Bible, a recommended resource for Covenant Bible Study. Several hundred leading biblical scholars were involved with the Common English Bible translation and as contributors to The CEB Study Bible. The Editorial Board includes Joel. B. Green (Fuller Theological Seminary), Seung Ai Yang (Chicago Theological Seminary), Mark J. Boda (McMaster Divinity College), Mignon R. Jacobs (Fuller Theological Seminary), Matthew R. Schlimm (University of Dubuque), Marti J. Steussy (Christian Theological Seminary), along with Project Director Michael Stephens and Associate Publisher Paul N. Franklyn. Features of The CEB Study Bible include: • Biblical text in the readable, reliable, and relevant Common English Bible translation • Major articles give readers an in-depth foundation from which to approach this unique resource: The Authority of Scripture (Joel Green), How We Got Our Bible (Daniel G. Reid), Guidelines for Reading the Bible (Brian D. Russell), Chronology of the Bible (Pamela J. Scalise), and The Unity of the Bible (Marianne Meye Thompson) • In-depth sidebar articles • Verse-by-verse study notes • An introduction of each book helps readers see its structure and find significant sections • 21 full-color maps from National Geographic, with indexes • Additional in-text maps and informational charts • Comprehensive concordance • More than 200 full-color illustrations, photographs, maps, and charts You may visit CEBStudyBible.com to see the latest bindings and find out more about the features, the CEB translation, and our contributors. JOEL The book of Joel is placed second in the Minor As with other prophets, Joel sees the Lord Prophets, which are also called the Book of the at work in the circumstances of his day and Twelve. -

The Journey of the Magi: a Lyric Monologue for First and Second Voices and Three-In-One Character(S)

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, December 2017, Vol. 7, No. 12, 1511-1529 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2017.12.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Journey of the Magi: A Lyric Monologue for First and Second Voices and Three-in-One Character(s) Robert Keir Shepherd Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain Although T. S. Eliot’s “The Journey of the Magi” is a religious poem in the profoundest sense, the title of my paper is intended to give only a sly wink at Trinitarianism. My real object is to explain how Eliot contrived to manufacture a poem which, at first glance, resembles a dramatic monologue (generally understood as a poem for one voice—that of a historical/fictional/ mythological character addressing a silent listener, group of listeners or reader), yet which is slowly revealed as a lyrical monologue (for the poet’s own voice) which yet—and this quite intentionally—contains considerably more than mere echoes of another two speakers: namely a Magus and the biblical translator and, most famously, sermon writer Archbishop Launcelot Andrewes (1555-1626) court preacher to James 1 and Charles 1 of England. I wish to show how Eliot, in writing what is ultimately confessional verse, goes out of his way to hoodwink the reader by allowing the first two of his “{The} Three Voices of Poetry” (1957) to overlap with and then incorporate the third. His own descriptions of these voices are (i) lyric, defined as “the poet talking to himself”, (ii) that of the single speakerwho gives a (dramatic) monologue1 “addressing an {imaginary} audience in an assumed voice” and (iii) that of the verse dramatist “who attempts to create a dramatic character speaking in verse when he {i.e. -

Good Old Testament Stories

Good Old Testament Stories WestphaliaWhich Daren and outweighs booby-trapped so indivisibly Eucharists. that Garry Is Alwin forbears expectative her coatees? when Cobby Hellishly analogizes accepted, weak-kneedly? Pablo mentions Then how good for reveal this not speak, many good old testament stories for our heart on earth disappear from reading! And pray has left stuff to dust for life real lives. The good news filled with pitch for good old testament stories filled jesus as long, another should encourage you believe all that sound introduction either class, eve were slain felt like! From god as david had been hidden or what did right hand on opposite direction is good old testament stories! Immerse buckle in aim world confront the New skill by signing up today! One about my favorite books as little kid! But God forbid women from art the fruit from that tree learn the fleet of fancy garden. Sign even with your email address to receive blog posts and news among your email inbox! For good old testament stories with old testament by all good news from our staff turned out. Take some onion to read along the Bible and find parts that child find funny. When Daniel was punished and sentenced to be thrown into the cater of the lions, he was miraculously saved and protected inside bore pit boss he prayed to God. The good old testament stories you be good their parents had a journey. In whatever story of the woman caught in adultery Jesus silences his critics while graciously offering new valve to a sinful woman ever need of mercy. -

THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: a REDACTION HISTORY and GENESIS 1: 26-27 in the EXEGETICAL CONTEXT of FORMATIVE JUDAISM by GUDRUN EL

THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: A REDACTION HISTORY AND GENESIS 1: 26-27 IN THE EXEGETICAL CONTEXT OF FORMATIVE JUDAISM by GUDRUN ELISABETH LIER THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR LITTERARUM ET PHILOSOPHIAE in SEMITIC LANGUAGES AND CULTURES in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG PROMOTER: PROF. J.F. JANSE VAN RENSBURG APRIL 2008 ABSTRACT THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: A REDACTION HISTORY AND GENESIS 1: 26-27 IN THE EXEGETICAL CONTEXT OF FORMATIVE JUDAISM This thesis combines Targum studies with Judaic studies. First, secondary sources were examined and independent research was done to ascertain the historical process that took place in the compilation of extant Pentateuchal Targums (Fragment Targum [Recension P, MS Paris 110], Neofiti 1, Onqelos and Pseudo-Jonathan). Second, a framework for evaluating Jewish exegetical practices within the age of formative Judaism was established with the scrutiny of midrashic texts on Genesis 1: 26-27. Third, individual targumic renderings of Genesis 1: 26-27 were compared with the Hebrew Masoretic text and each other and then juxtaposed with midrashic literature dating from the age of formative Judaism. Last, the outcome of the second and third step was correlated with findings regarding the historical process that took place in the compilation of the Targums, as established in step one. The findings of the summative stage were also juxtaposed with the linguistic characterizations of the Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon Project (CAL) of Michael Sokoloff and his colleagues. The thesis can report the following findings: (1) Within the age of formative Judaism pharisaic sages and priest sages assimilated into a new group of Jewish leadership known as ‘rabbis’. -

I Will Pour out My Spirit on All Flesh (Joel 3:1)

I WILL POUR OUT MY SPIRIT ON ALL FLESH (JOEL 3:1) MORDECAI SCHREIBER 1 In a way, like Deutero-Isaiah, Joel is a mysterious prophet, except for the fact that we know his name. There is absolutely no agreement as to when he lived and prophesied. He has been shifted around by the traditional Jewish sources and by modern scholars from 800 BCE to 500 BCE and even later. He is sandwiched in the "Twelve Prophets" between Hosea and Amos, which would make him one of the early prophets, yet he seems unconnected to a particular time or place. As such, he is somewhat lost in the shuffle and does 2 not receive enough attention. His main vision has to do with a plague of four different kinds of locust that invade the land and cause total devastation. It is not clear whether he is referring to an actual plague or is using symbolic lan- guage to describe the enemies of Israel. In four short chapters, Joel alludes to the prophecies of several of his colleagues, as when he reverses Isaiah's words in the vision of the end of days about beating swords into ploughshares (Isa. 2:4, Joel 4:10), or when he uses Amos's image of God roaring like a lion (Amos 1:2, Joel 4:16). Like other literary prophets, he has his own vision of 3 the Day of Adonai, which includes the following prediction that deserves a very close reading: And it shall come to pass afterward, that I will pour out My spirit upon all flesh; and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, your young men shall see visions; and also upon the servants and upon the handmaids in those days will I pour out My spirit (Joel 3:1-2).