A Canonical-Critical Study of Selected Traditions in the Book of Joel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7

Chapter 20 4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7 Gaye Strathearn am personally grateful for S. Kent Brown. He was a commit- I tee member for my master’s thesis, in which I examined 4Q521. Since that time he has been a wonderful colleague who has always encouraged me in my academic pursuits. The relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian- ity has fueled the imagination of both scholar and layperson since their discovery in 1947. Were the early Christians aware of the com- munity at Qumran and their texts? Did these groups interact in any way? Was the Qumran community the source for nascent Chris- tianity, as some popular and scholarly sources have intimated,¹ or was it simply a parallel community? One Qumran fragment that 1. For an example from the popular press, see Richard N. Ostling, “Is Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls?” Time Magazine, 21 September 1992, 56–57. See also the claim that the scrolls are “the earliest Christian records” in the popular novel by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 245. For examples from the academic arena, see André Dupont-Sommer, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Preliminary Survey (New York: Mac- millan, 1952), 98–100; Robert Eisenman, James the Just in the Habakkuk Pesher (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 1–20; Barbara E. Thiering, The Gospels and Qumran: A New Hypothesis (Syd- ney: Theological Explorations, 1981), 3–11; Carsten P. Thiede, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 152–81; José O’Callaghan, “Papiros neotestamentarios en la cueva 7 de Qumrān?,” Biblica 53/1 (1972): 91–100. -

Graduation Exercises Friday Morning, June Third at Ten O'clock

(?ARLETON eOLLEGE eighty,sixth cAnnual t'0mmencement 1960 Graduation Exercises Friday morning, June third at ten o'clock THE COMMON North of Skinner Memorial Chapel Northfield, Minnesota 'Program *THE ACADEMIC PROCESSION THE INVOCATION ANTHEM: Ye Shall Have a Song Thompson COMMENCEMENT AnDRESS JULIUS A. STRATTON, Sc.D. President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology ALUMNI AWARDS CONFERRING OF BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREES CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES THE BENEDICTION THE RECESSION *The audience is requested to remain seated throughout the pro gram, standing only for the benediction and the recession. SENIOR HONORS HONORS IN A FIELD OF CONCENTRATION LINDA MAY BUSWELL PSYCHOLGY Thesis: A Statistical Model of Learning ALISON APRIL KROTTER MATHEMATICS Thesis: Geometric Algebra JOHN WESLEY LANGO PHILOSOPHY Thesis: A Critical Comparison of Sartre and Wittgenstein JUNE LORRAINE MATTHEWS PHYSICS Thesis: A Semicircular Focusing Beta-Ray Spectrometer LAWRENCE PERLMAN GOVERNMENT AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Thesis: The Urban Renewal Program in St. Paul and Minneapolis: A Study in Intergovernmental Relations JAMES ALAN PLAMBECK CHEMISTRY Thesis: Logarithmic Equilibrium Diagrams KATHERINE ANN RANKIN ENGLISH Thesis: Order, an Ideal of T. S. Eliot JOEL SAMUEL RICHMON BIOLOGY Thesis: An Experimental Investigation of Colchicine Induced Strophosomy in the Chick Embryo DAVID ROBERT RINGROSE HISTORY Thesis: The Development of Turkey and Yugoslavia Since World War II STANFORD KENNETH ROBINS PHILOSOPHY Thesis: John Dewey's Theory of Valuation FLORENCE PALMER STAPLIN ENGLISH Thesis: Theme and Structure in Three Late Novels by Dickens DISTINCTION IN A DEPARTMENT LOIS-MARY ApPLE JEROME LERoy LONNES Biology Philosophy BENNET BRISTOL BRABSON ROBERT OELHAF Physics Physics LINDA MAY BUSWELL LAWRENCE PERLMAN Psychology Government and International Relations MARY T. -

And the Goal of New Testament Textual Criticism

RECONSTRUCTING THE TEXT OF THE CHURCH: THE “CANONICAL TEXT” AND THE GOAL OF NEW TESTAMENT TEXTUAL CRITICISM by DAVID RICHARD HERBISON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Biblical Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Kent Clarke, Ph.D.; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Craig Allert, Ph.D.; Second Reader TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY December 2015 © David Richard Herbison ABSTRACT Over the last several decades, a number of scholars have raised questions about the feasibility of achieving New Testament textual criticism’s traditional goal of establishing the “original text” of the New Testament documents. In light of these questions, several alternative goals have been proposed. Among these is a proposal that was made by Brevard Childs, arguing that text critics should go about reconstructing the “canonical text” of the New Testament rather than the “original text.” However, concepts of “canon” have generally been limited to discussions of which books were included or excluded from a list of authoritative writings, not necessarily the specific textual readings within those writings. Therefore, any proposal that seeks to apply notions of “canon” to the goals and methods of textual criticism warrants further investigation. This thesis evaluates Childs’ -

3 the Issue of Methodology Regarding Inner-Biblical and Inter-Biblical Interpretation: Rhetorical Criticism

3 The Issue of Methodology Regarding Inner-Biblical and Inter-Biblical Interpretation: Rhetorical Criticism In our last chapter, we delineated discourse analysis (text-linguistics) as one of the two methodological approaches we will apply in this project. In this chapter, we will examine our second methodological approach, rhetorical criticism, under the rubric of literary analysis. Literary analysis83 has a protracted history that encompasses a variety of methodologies that stretch beyond the scope of this project. While we refer to scholarly works that treat and discuss these subjects,84 our course of action is to focus on one of the methodologies and consider how it can be applied to our study. Literary analysis includes the following methodologies: source, tradition- historical, form, redaction, canonical, and rhetorical criticism.85 Regardless of the methodologies chosen, the aim of applying literary criticism to biblical studies – to borrow John Barton’s term – is for the ‟elucidation” of the biblical texts.86 After reviewing all the critical methods, we have settled on rhetorical criticism. The reasons why we have chosen rhetorical criticism above other methods of literary analysis serve as the subject of our next section. 83 Traditionally, literary criticism is also known as source criticism. It should be noted that we are using literary analysis and literary criticism synonymously, putting textual, form, source, rhetorical, and canonical criticism under literary analysis. See T. K. Beal, K. A. Keefer, and T. Linafelt, ‟Literary Theory, Literary Criticism, and the Bible,” in DBI 2: 79. Richard Coggins, ‟Keeping Up with Recent Studies X: The Literary Approach to the Bible,” ExpTim 96 (1984): 9-14. -

The Book of Joel

Charles Savelle Center Point Bible Institute 1 THE BOOK OF JOEL Message: The message to Joel is fairly straightforward. Basically, it is that, “The Day of the Lord is coming to bring judgment for God’s enemies and restoration for God’s people.” Joel sets his message up by pointing to a literal locust plague which he poetically morphs into a eschatological Day of the Lord. Or as Finley puts it, “The prophecy of Joel can be compared to two wheels turning on an axle. The wheels are history and eschatology, while the axle is the day of the Lord.”1 Author: According to 1:1, the human author of the prophecy was Joel son of Pethuel. Joel means “Yahweh is God.” The name was fairly popular and there are eleven to fourteen men who bear this designation in the Old Testament depending on how you count them. The references to “Zion” and “the house of the Lord” (1:9, 13–14; 2:15–17, 23, 32; 3:1, 5–6, 16–17, 20–21) might indicate that the prophet was a resident of Jerusalem. References to the priesthood (1:13–14; 2:17) might indicate that Joel was a priest. Nothing is known about his father Pethual. Recipients: The identification of the original recipients is tied closely to the issue of dating. While most would hold that the oracle was written to Judah, dating affects whether we are referring to pre-exilic or exilic Judah. Since an early date seems more likely, the original recipients are likely pre-exilic Israel. -

HERMENEUTICAL CRITICISMS: by Mark E

Issues of Interpretation Ozark Christian College, GB 216-2 Professor Mark E. Moore, Ph.D. Table of Contents: 1. Hermeneutical Constructs .......................................................................................................2 2. A Chart of the History of Hermeneutics .................................................................................5 3. History of Interpretation .........................................................................................................7 4. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 1.1.10.......................................................................29 5. Allegory of 153 Fish, Jn 21:11 .............................................................................................30 6. How the Holy Spirit Helps in Interpretation .........................................................................31 7. Problem Passages ..................................................................................................................32 8. Principles for Dealing with Problem Passages .....................................................................33 9. Cultural vs. Universal ...........................................................................................................34 10. Hermeneutical Constructs .....................................................................................................36 11. Hermeneutical Shifts .............................................................................................................38 12. Hermeneutical Constructs: -

The Modern History of the Qumran Psalms Scroll and Canonical Criticism

THE MODERN HISTORY OF THE QUMRAN PSALMS SCROLL AND CANONICAL CRITICISM JAMES A. SANDERS At its 2001 annual meeting the international Society of Biblical Literature celebrated the completion of the publication of the Dead Sea Serolls. It was a gala occasion with a sense of the miraculous hovering over the some three hundred who attended. In the previ ous five decades eight volumes of the Discovenes in the Judaean Desert scries had been published, but during the last decade twenty-eight more have appeared. Emanuel Tov, Magnes Professor of Hebrew Bible at the Hebrew University, made the difference. In 1990 Tov became the fourth chief editor of the international team charged with thc pub1ications, following Roland de Vaux, Pierre Benoit, and John Strugnell. Tov increased the team from twenty scholars to over sixty. Five further volumes are in the pipeline at the present, which will complete publication of thirty-nine volumes of the scrolls in thc DJD series, over nine-hundred ancient texts all told. Reference vol umes will follow. Tov's address on the occasion was stunning. It was a tell-all, detailed history of publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls from his stand point, and as only he with his intimate knowledge of the last phases of the enterprise could tell it. I It was a kind of oral history of thc sort Sterling Van Wagner and Weston Fields, an editor of the present volume, and others have recently been collecting from the earlier generation of Dead Sea Scrolls scholars. One weeps over the lost, unpublished records that have languished in widows' and heirs' attics, when the source of the most intimatc kind of knowledge has been totally lost in the deaths of those who failed to complete their work, or who were too modest to publish their memories of what really happened. -

God, Abraham, and the Abuse of Isaac

Word & World Volume XV, Number 1 Winter 1995 God, Abraham, and the Abuse of Isaac TERENCE E. FRETHEIM Luther Seminary St. Paul, Minnesota HIS IS A CLASSIC TEXT.1 IT HAS CAPTIVATED THE IMAGINATION OF MANY INTER- Tpreters, drawn both by its literary artistry and its religious depths. This is also a problem text. It has occasioned deep concern in this time when the abuse of chil- dren has screamed its way into the modern consciousness: Is God (and by virtue of his response, Abraham) guilty of child abuse in this text? There is no escaping the question, and it raises the issue as to the continuing value of this text. I. MODERN READINGS Psychoanalyst Alice Miller claims2 that Genesis 22 may have contributed to an atmosphere that makes it possible to justify the abuse of children. She grounds her reflections on some thirty artistic representations of this story. In two of Rem- brandt’s paintings, for example, Abraham faces the heavens rather than Isaac, as if in blind obedience to God and oblivious to what he is about to do to his son. His hands cover Isaac’s face, preventing him from seeing or crying out. Not only is Isaac silenced, she says (not actually true), one sees only his torso; his personal fea- tures are obscured. Isaac “has been turned into an object. He has been dehuman- ized by being made a sacrifice; he no longer has a right to ask questions and will 1This article is a reworking of sections of my commentary on Genesis 22 in the New Interpreters Bi- ble (Nashville: Abingdon, 1994) 494-501. -

Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11

God's Master Plan In Prophecy Lesson 13 – The Battle of Armageddon & 2nd Coming of Jesus Christ Key Scriptures: Revelation 19:1-21 Ezekiel 38 & 39 Joel 2:1-11 Zechariah 12-14 Introduction Rev 19:1 After these things I heard something like a loud voice of a great multitude in heaven, saying, "Hallelujah! Salvation and glory and power belong to our God; While the Wrath of God is being poured out, there was the voice of "a great multitude in heaven" praising God! This is the redeemed church which has missed the Wrath of God and was taken out of Great Tribulation. While the earth is experiencing the judgment of God without mercy, we are experiencing His goodness without judgment! Rev 19:2-3 BECAUSE HIS JUDGMENTS ARE TRUE AND RIGHTEOUS; for He has judged the great harlot who was corrupting the earth with her immorality, and HE HAS AVENGED THE BLOOD OF HIS BOND-SERVANTS ON HER." 3 And a second time they said, "Hallelujah! HER SMOKE RISES UP FOREVER AND EVER." From what is being said in these verse, it is obvious that the church will be fully aware of what is happening upon the earth during this time, yet because we are no longer viewing earth's events through the eyes of mortal flesh, we will understand that God is righteous and true in His judgments. To modern minds it may seem strange to worship and say, “hallelujah” over the fact that God is pouring out judgment, but that is because we see imperfectly now. -

The Minor Prophets Michael B

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 6-26-2018 A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets Michael B. Shepherd Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Michael B., "A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets" (2018). Faculty Books. 201. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets Keywords Old Testament, prophets, preaching Disciplines Biblical Studies | Religion Publisher Kregel Publications Publisher's Note Taken from A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © Copyright 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd. Published by Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ISBN 9780825444593 This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE KREGEL EXEGETICAL LIBRARY A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE The Minor Prophets MICHAEL B. SHEPHERD Kregel Academic A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-6020. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in printed reviews. -

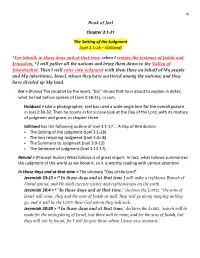

Book of Joel Chapter 3:1-21 the Setting of the Judgment (Joel 3:1

(1) Book of Joel Chapter 3:1-21 The Setting of the Judgment (Joel 3:1-2b – Gilliland) 1 For behold, in those days and at that time, when I restore the fortunes of Judah and Jerusalem, 2 I will gather all the nations and bring them down to the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Then I will enter into judgment with them there on behalf of My people and My inheritance, Israel, whom they have scattered among the nations; and they have divided up My land. For > (Pusey) The prophet by the word, "for," shows that he is about to explain in detail, what he had before spoken of (Joel 2:18-31), in sum. Hubbard > Like a photographer, Joel has used a wide-angle lens for the overall picture in Joel 2:30-32. Then he zooms in for a close look at the Day of the Lord, with its mixture of judgment and grace, in chapter three Gilliland has the following outline of Joel 3:1-17 … A Day of Retribution . The Setting of the Judgment (Joel 3:1-2b) . The Sins requiring Judgment (Joel 3:2c-8) . The Summons to Judgment (Joel 3:9-12) . The Sentence of Judgment (Joel 3:13-17). Behold > (Precept Austin) What follows is of great import. In fact, what follows summarizes the judgment of the world as we know it, so it is worthy reading with utmost attention. In those days and at that time > The ultimate “Day of the Lord” Jeremiah 33:15 > 15 In those days and at that time I will make a righteous Branch of David sprout; and He shall execute justice and righteousness on the earth. -

The Book of Joel: Anticipating a Post-Prophetic Age

HAYYIM ANGEL The Book of Joel: Anticipating a Post-Prophetic Age Introduction OF THE FIFTEEN “Latter Prophets”, Joel’s chronological setting is the most difficult to identify. Yet, the dating of the book potentially has significant implications for determining the overall purposes of Joel’s prophecies. The book’s outline is simple enough. Chapters one and two are a description of and response to a devastating locust plague that occurred in Joel’s time. Chapters three and four are a prophecy of consolation predict- ing widespread prophecy, a major battle, and then ultimate peace and pros- perity.1 In this essay, we will consider the dating of the book of Joel, the book’s overall themes, and how Joel’s unique message fits into his likely chronological setting.2 Dating Midrashim and later commentators often attempt to identify obscure figures by associating them with known figures or events. One Midrash quoted by Rashi identifies the prophet Joel with the son of Samuel (c. 1000 B.C.E.): When Samuel grew old, he appointed his sons judges over Israel. The name of his first-born son was Joel, and his second son’s name was Abijah; they sat as judges in Beer-sheba. But his sons did not follow in his ways; they were bent on gain, they accepted bribes, and they subvert- ed justice. (I Sam. 8:1-3)3 RABBI HAYYIM ANGEL is the Rabbi of Congregation Shearith Israel. He is the author of several books including Creating Space Between Peshat & Derash: A Collection of Studies on Tanakh. 21 22 Milin Havivin Since Samuel’s son was wicked, the Midrash explains that he must have repented in order to attain prophecy.