Investing in Public Urban Greenspace Is Now More Essential Than Ever in the US and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiac Rehabilitation in German Speaking Countries of Europe—Evidence-Based Guidelines from Germany, Austria and Switzerland Llkardreha-DACH—Part 2

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Cardiac Rehabilitation in German Speaking Countries of Europe—Evidence-Based Guidelines from Germany, Austria and Switzerland LLKardReha-DACH—Part 2 Bernhard Schwaab 1,2,* , Birna Bjarnason-Wehrens 3, Karin Meng 4, Christian Albus 5, Annett Salzwedel 6 , Jean-Paul Schmid 7 , Werner Benzer 8, Matthes Metz 9, Katrin Jensen 9,†, Bernhard Rauch 10,11, Gerd Bönner 12,‡, Patrick Brzoska 13,‡, Heike Buhr-Schinner 14,‡, Albrecht Charrier 15,‡, Carsten Cordes 16,‡, Gesine Dörr 17,‡, Sarah Eichler 6,‡, Anne-Kathrin Exner 18,‡, Bernd Fromm 19,‡, Stephan Gielen 18,‡, Johannes Glatz 20,‡, Helmut Gohlke 21,‡, Maurizio Grilli 22,‡ , Detlef Gysan 23,‡, Ursula Härtel 24,‡, Harry Hahmann 25,‡, Christoph Herrmann-Lingen 26,‡, Gabriele Karger 27,‡, Marthin Karoff 28,‡, Ulrich Kiwus 29,‡, Ernst Knoglinger 30,‡, Christian-Wolfgang Krusch 31,‡, Eike Langheim 20,‡, Johannes Mann 32,‡, Regina Max 33,‡, Maria-Inti Metzendorf 34,‡ , Roland Nebel 35,‡ , Josef Niebauer 36,‡ , Hans-Georg Predel 3,‡, Axel Preßler 37,‡, Oliver Razum 38,‡ , Nils Reiss 39,‡, Daniel Saure 9,‡, Clemens von Schacky 40,‡, Morten Schütt 41,‡, Konrad Schultz 42,‡ , Eva-Maria Skoda 43,‡, Diethard Steube 44,‡, Marco Streibelt 45,‡, Martin Stüttgen 46,‡, Michaela Stüttgen 47,‡, Martin Teufel 43,‡, Hansueli Tschanz 48,‡, Heinz Völler 6,49,‡, Heiner Vogel 50,‡ and Ronja Westphal 51,‡ 1 Curschmann Klinik, D-23669 Timmendorfer Strand, Germany 2 Medizinische Fakultät, Universität zu Lübeck, D-23562 Lübeck, Germany Citation: Schwaab, B.; 3 Institute for Cardiology and Sports Medicine, Department of Preventive and Rehabilitative Sport- and Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; Meng, K.; Exercise Medicine, German Sportuniversity Cologne, D-50933 Köln, Germany; Albus, C.; Salzwedel, A.; Schmid, J.-P.; [email protected] (B.B.-W.); [email protected] (H.-G.P.) Benzer, W.; Metz, M.; Jensen, K.; 4 Institute for Clinical Epidemiology and Biometry (ICE-B), University of Würzburg, D-97080 Würzburg, Rauch, B.; et al. -

KOOKABURRA 1992 PRESBYTERIAN LADIES' COLLEGE 1992 COUNCIL the Moderator of the Uniting Church in WA Rev

) KOOKABURRA 1992 PRESBYTERIAN LADIES' COLLEGE 1992 COUNCIL The Moderator of the Uniting Church in WA Rev. P Sindle, B.A. Hon. MJ Craig, Chairman Mrs J Thompson, LL.B., B.A. (nom. by the OCA) Mrs S Andrew Prof. N Tuckwell, B.A.. B.Ed.(Hons)., M.Ed .. MrR EArgyle Grad.Dip.Admin., M.Ed.Admin .. Ph.D Mr F Crawley, F.C.A. (nom. by the Parents' Assoc.) Mr J Farrell, B.Sc., T.Cen., MAC.S. Life Members Mr RI Fitzpatrick, M.B.B.S. (Melb)., F.R.C.S. (England).. Mr FG Barr. J.P., BA. Dip.Ed. F.R.A.C.S. (nom. by the Parents' Assoc.) Mrs V Hill Mrs H Grzyb, A.I.M.M. (nom. by the OCA) Mr J Livingston Mr T Humphry, B.Eng. (Hons). Mr C Snowden, F.C.I.V. Dr P. Kailis, O.B.E., M.B.B.S. Mrs F Stimson Rev. B May Mr M Murray, B.Comm. Secretary to the College Mr H Plaistowe, F.A.S.A. Mr TM Gorey. F.C.A. Principal: MIs HJ Day B.A., Dip.Ed., L.Mus., L.Te.L., Visiting Specialists: AAS.A., MAe.E., F.I.E.A., A.FAI.M. STAFF Mr ABridge - Music - Percussion Mr 0 Coughlan - Music - Viola Director of Pastoral Care and Discipline, Senior Other Academic StafT: Mr SFairbairn A.R.e.M .. L.Te.L. -Music -Clarinet Resident-in-Charge Boarding House and Deputy Miss TFiebig - Music -Cello Principal: MIs GBull Dip.Home Sc., Teach.Cel1., MAe.E. Ms TAndrews DipTeach. -

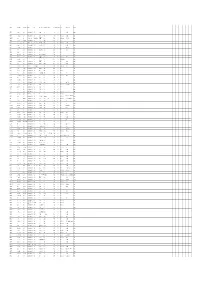

Wfdwa-Rsl-181112

SURNAME FIRST NAMES RANK at Death REGIMENT UNIT WHERE BORN BORN STATE HONOURS DOD (DD MMM) YOD (YYYY) COD PLACE OF DEATH COUNTRY A'HEARN Edward John Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Wilcannia NSW 4 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium AARONS John Fullarton Private Australian Infantry, AIF 16th Bn Hillston NSW 11 Jul 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France Manchester, ABBERTON Edmund Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Div Signal Coy England 6 Nov 1918 DOI (Illness, acute) 1 AAH, Harefield England Lancashire ABBOTT Charles Edgar Lance Corporal Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Avoca Victoria 30 May 1916 KIA - France ABBOTT Charles Henry Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Tunnelling Coy Maryborough Victoria 26 May 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France ABBOTT Henry Edgar Private Australian Army Medical Corp10th AFA Burra or Hoylton SA 12 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium ABBOTT Oliver Oswald Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Hoyleton SA 22 Aug 1916 KIA Mouquet Farm France ABBOTT Robert Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Malton, Yorkshire England 25 Jul 1916 KIA France France ABOLIN Martin Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Riga Russia 10 Jun 1917 KIA - Belgium ABRAHAM William Strong Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Mepunga, WarnnamboVictoria 25 Jul 1916 KIA - France Southport, ABRAM Richard Private Australian Infantry, AIF 28th Bn England 29 Jul 1916 Declared KIA Pozieres France Lancashire ACKLAND George Henry Private Royal Warwickshireshire Reg14th Bn N/A N/A 8 Feb 1919 DOI (Illness, acute) - England Manchester, ACKROYD -

Acknowledgments

206 DOING BUSINESS IN THE ARAB WORLD 2010 Acknowledgments Doing Business 2011 was prepared by a The Doing Business team is grateful for team led by Sylvia Solf, Penelope Brook valuable comments provided by col- (through May 2010) and Neil Gregory (from leagues across the World Bank Group June 2010) under the general direction and for the guidance of World Bank of Janamitra Devan. The team comprised Group Executive Directors. Svetlana Bagaudinova, Jose Becerra Marta, Karim O. Belayachi, Frederic Bustelo, César Oliver Hart and Andrei Shleifer provided Chaparro Yedro, Maya Choueiri, Santiago academic advice on the project. The pay- Croci Downes, Karen Sarah Cuttaree, Marie ing taxes project was conducted in collab- Contact details for local partners Delion, Allen Dennis, Jacqueline den Otter, oration with PricewaterhouseCoopers, led are available on the Doing Raian Divanbeigi, Alejandro Espinosa- by Robert Morris. The development of the Business website at Wang, Antonio Garcia Cueto, Carolin getting electricity indicators was financed Geginat, Cemile Hacibeyoglu, Betina by the Norwegian Trust Fund. http://www.doingbusiness.org Hennig, Sabine Hertveldt, Mikiko Imai Ollison, Ludmila Januan, Nan Jiang, Palarp Alison Strong copyedited the manuscript. Jumpasut, Dahlia Khalifa, Eugenia Levine, Gerry Quinn designed the report and Jean Michel Lobet, Valerie Marechal, the graphs. Alexandra Quinn and Karen Andres Martinez, Frederic Meunier, Jackson provided desktopping services. Alexandra Mincu, Robert Murillo, Joanna Nasr, Titilayo Oke, Oleksandr Olshanskyy, The report was made possible by the gen- Dana Omran, Caroline Otonglo, Yara Salem, erous contributions of more than 8,200 Pilar Salgado-Otónel, Jayashree Srinivasan, lawyers, accountants, judges, business- Susanne Szymanski, Tea Trumbic, Marina people and public officials in 183 econo- Turlakova and Lior Ziv. -

2012 Publications by Department Anesthesiology 2012 Publications 1. Bamberger D, Goers

2012 Publications by Department Anesthesiology 2012 Publications 1. Bamberger D, Goers M, Quinn T, Herndon B. Reduction of beta-lactam antimicrobial activity in Staphylococcus aureus abscesses by neutrophil alteration of penicillin-binding protein 2. Advances in Infectious Diseases , doi:10.4236/aid.2012, in press May 2012. 2. Buch S, Yao H, Guo M, Mori T, Seth P, Wang J, Su TP (2012) Cocaine and HIV-1 interplay in CNS: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Curr HIV Res in press. 3. Carino C, Fibuch EE, Mao LM and Wang JQ. (2012) Dynamic loss of surface-expressed AMPA receptors in mouse cortical and striatal neurons during anesthesia. J Neurosci-Res 90:315-323. 4. Chu XP, Jing L, Jiang YQ, Collier DM, Wang B, Jiang Q, Synder PM, Zha XM. N-glycosylation of ASICIa regulates its trafficking and acidosis-induced spine remodeling. (2012) J Neurosci 32:4080-4091. 5. Elliott J, Opper S, Agarwal S, Fibuch EE. Non-analgesic effects of opioids: Opioids and the endocrine system. (An Invited Review). 2012. Current Pharmaceutical Design. Accepted for publication March 2012. 6. Ferns J, Theisen CS, Fibuch EE, Seidler NW. Protection against protein aggregation by alpha- crystallin as a mechanism of preconditioning. 2012. Neurochem Res. 37:244-252. 7. Fibuch EE, VanWay, C. Succession Planning – PEJ (accepted for publication Jan 2012) 8. Fibuch EE. The opioid conundrum. 2012. Accepted for publication. Metropolitan Medical Journal. 9. Fibuch EE. Van Way C. Sustainability: A fiduciary responsibility of senior leaders. 2012. PEJ. March-April. Pp 36-43. 10. Guo ML, Xue B, Jin DZ, Liu ZG, Fibuch EE, Mao LM, Wang JQ. -

Hamilton County (Ohio) Naturalization Records – Surname P Through R

Hamilton County Naturalization Records – Surname P through R Applicant Age Country of Origin Departure Date Departure Port Arrive Date Entry Port Declaration Dec Date Naturalization Naturalization Date Restored Date Vol Page Folder Pabst, Konrad 41 Germany 4/3/1883 Bremen 4/14/1883 New York T 02/21/1882 F T Pace, Agostina 26 Italy 6/7/1892 Naples 7/7/1892 New York T 10/18/1899 F T Pace, Biaggio 56 Italy 3/25/1879 Naples 4/15/1879 New York T 10/22/1900 F T Pace, Giacomo 32 Italy 7/10/1888 Palermo 8/1/1888 New York T 10/17/1893 F 21 16 F Pace, Giacomo 32 Italy 7/10/1888 Palermo 8/1/1888 New York T 10/17/1893 F T Pachet, Francis 17 France New York F T 10/22/1888 T Pade, William 27 Switzerland 6/14/1885 Havre 6/23/1885 New York T 10/31/1893 F T Padley, Herbert 42 England 6/6/1872 Liverpool 10/26/1878 Cincinnati? T 02/20/1886 F 10/20/1886 T Padmore, Albert Edward 19 England ? T 07/20/1886 F T Paetow, Otto 34 Germany 7/28/1881 Hamburg 8/11/1881 New York T 11/25/1889 F T Paffryman, James 33 England 8/10/1853 Liverpool 9/17/1853 New York T 09/08/1857 F 15 244 F Pagani, Gaetano 46 Italy 4/22/1885 Genova 5/22/1885 New York T 10/25/1900 F T Page, Noah 42 England 8/28/1868 Liverpool 9/12/1868 New York T 11/04/1889 F T Pagel, Otto 21 Germany 4/22/1893 Bremen 4/29/1893 New York T 06/15/1896 F T Pagenhardt, Julius Germany ? T 12/24/1888 F T Pahl, Anthony 29 Germany 1/12/1870 Winterberg 2/7/1870 New York T 11/05/1880 F T Pahls, Heinrich 33 Oldenburg 5/15/1860 Bremen 7/29/1860 Baltimore T 11/01/1860 F 27 44 F Pahls, Henry 23 Germany 9/28/1882 Rotterdam -

Geochemical Database of Feed Coal and Coal Combustion Products (Ccps) from Five Power Plants in the United States

Geochemical Database of Feed Coal and Coal Combustion Products (CCPs) from Five Power Plants in the United States Selected Coal Utilization References By Kelly L. Conrad and Ronald H. Affolter Pamphlet to accompany Data Series 635 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 About USGS Products For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS About this Product Publishing support provided by Denver Science Publishing Network For more information concerning this publication, contact: Center Director, USGS Central Energy Resources Science Center Box 25046, Mail stop 939 Denver, CO 80225 (303) 236-7775 or visit the Central Energy Resources Science Center Web site at: http://energy.cr.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Affolter, R.H., Groves, Steve, Betterton, W.J., Benzel, William, Conrad, K.L., Swanson, S.M., Ruppert L.F., Clough J.G., Belkin, H.E., Kolker, Allan, and Hower, J.C., 2011, Geochemical database of feed coal and coal combustion products (CCPs) from five power plants in the United States: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 635, pamphlet, 19 p. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Attachment A'

'ATTACHMENT A' WARRANT OF PAYMENTS - BY VENDOR FOR MONTH OF OCTOBER 2004 Payment Payment No Payment Date Payment Amount Vendor Method 956 27-Oct-04 EFT 180.00 4 D INTERIORS 67603 14-Oct-04 CHEQUE 320.00 A1 PHOTOGRAPHY 67531 07-Oct-04 CHEQUE 341.88 AAA PRODUCTION SERVICES 969 27-Oct-04 EFT 2,628.66 AAPT LIMITED 67642 14-Oct-04 CHEQUE 88.00 ABA 67672 19-Oct-04 CHEQUE 481.25 ABIBU IN HOME COMPUTING 934 13-Oct-04 EFT 200.00 ABOUT BIKE HIRE 970 27-Oct-04 EFT 275.00 ACCONCI CONCEPTS PTY LTD 67762 25-Oct-04 CHEQUE 1,265.00 ACE VERMIN & PEST CONTROL 67761 25-Oct-04 CHEQUE 154.00 A CLASS LINEMARKING SERVICE 964 27-Oct-04 EFT 1,492.70 ACTION GLASS & ALUMINIUM 67557 07-Oct-04 CHEQUE 277.50 ADRIAN COCKS REAL ESTATE 67753 21-Oct-04 CHEQUE 600.00 ADRIAN KINSEY 963 27-Oct-04 EFT 34.94 AIR LIQUIDE WA PTY LTD 967 27-Oct-04 EFT 430.16 AIRLITE CLEANING PTY LTD 67747 21-Oct-04 CHEQUE 1,100.00 A K & J D OTTER 931 13-Oct-04 EFT 1,320.00 ALEX MANFRIN 961 27-Oct-04 EFT 1,110.48 ALGAR BURNS PTY LTD 67530 07-Oct-04 CHEQUE 711.90 ALINTA 67583 08-Oct-04 CHEQUE 351.85 ALINTA 67600 14-Oct-04 CHEQUE 100.00 ALINTA 67680 20-Oct-04 CHEQUE 68.30 ALINTA 67681 20-Oct-04 CHEQUE 832.00 ALINTA 67952 29-Oct-04 CHEQUE 422.95 ALINTA 958 27-Oct-04 EFT 101.09 ALLMARK & ASSOCIATES 962 27-Oct-04 EFT 54,792.11 ALPHAWEST SERVICES PTY LTD 67726 21-Oct-04 CHEQUE 500.00 AMAD MHER 67737 21-Oct-04 CHEQUE 500.00 AMANDA SPEED 938 13-Oct-04 EFT 1,077.00 AMCOM PTY LTD 67586 13-Oct-04 CHEQUE 8.00 AMERICAN HOME ASSURANCE COMPANY 67871 26-Oct-04 CHEQUE 8.00 AMERICAN HOME ASSURANCE COMPANY 67688 -

Dean's List | Illinois Students

Univeristy of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign | Fall 2011 | Dean's List | Illinois Students Middle Student City ZIP Last Name First Name College Major Name Class Addison Adams Sarah Elizabeth 3 Agricultural, Consumer & Environmental Sciences Animal Sciences Addison Cruce Justin T 1 Engineering Civil Engineering Addison Foster Kayla E 1 Liberal Arts & Sciences Biology Addison Gerth Christopher M 2 Engineering Electrical Engineering Addison Kelly Rebecca R 1 Agricultural, Consumer & Environmental Sciences Food Science & Human Nutrition Addison Kwee Dustin J 1 Business Curric Unassigned Addison Patel Megh J 1 Liberal Arts & Sciences Molecular and Cellular Biology Addison Ramir Tyler J 2 Division of General Studies Undeclared Addison Ramirez Amanda Marie 4 Liberal Arts & Sciences Psychology Addison Rowley Jennifer Marie 2 Liberal Arts & Sciences English Addison Saporito Daniela Clara 4 Liberal Arts & Sciences Communication Algonquin Badmus Oyindamola Hanna Y2 Law Law Algonquin Blunk Melissa Kelly 3 Applied Health Sciences Recreation, Sport & Tourism Algonquin Demetriou Nicholas P 1 Engineering Materials Science & Engineering Algonquin Dobbelaere Andie V 2 Business Marketing Algonquin Dombrowski Anthony J 3 Fine & Applied Arts Architectural Studies Algonquin Gardeck Matthew John 4 Business Accountancy Algonquin Kaczar Brian C 1 Business Curric Unassigned Algonquin Kale Brett W 1 Business Curric Unassigned Algonquin Koniewicz Kristen L 2 Liberal Arts & Sciences Biology Algonquin Kunzweiler Christopher K 4 Business Accountancy Algonquin Lindgren -

June 2, 2017 Contact: UM Registrar's Office, 406-243-2995. Montana

June 2, 2017 Contact: UM Registrar’s Office, 406-243-2995. Montana Students Make UM Dean’s List MISSOULA – At the University of Montana, 2,743 students made the spring semester 2017 Dean’s List and President’s 4.0 List. To qualify for the Dean’s List or President’s 4.0 List, students must be undergraduates, earn a semester GPA of 3.5 or higher and receive grades of A or B in at least nine credits. Students who receive any grade of C+ or below or no credit (NC/NCR) in a course are not eligible. The Montana students listed below made UM’s spring semester 2017 Dean’s List or the President’s 4.0 List. Double asterisks after a name indicate the student earned a 4.0 GPA. A single asterisk indicates a GPA greater than 3.5 but less than 4.0. This information also is available online at: http://bit.ly/2lSUmDd. -

Kookaburra-1991-Smaller.Pdf

PRESBYTERIAN LADIES' COLLEGE A College of the Uniting Church in Australia KOO URRA 1991 Cover photo: by S. Angus Yr 12 14 McNeil Street, Peppermint Grove, Western Australia Tel: (09) 383 3887 Fax: (09) 383 1824 Editorial 3 Ferguson 14 Kindergarten 55 Principal's Report 4 McNeil 16 Junior School 56 Head Prefect's Report 5 Stewart 18 Dances 62 Boarding House Report 6 Summers 20 School Organisation 66 Service '91 8 Arts Report 23 Student Council 9 Music 27 Art and Literature 67 Baird JO Sports 35 Years 8-11 74 Carmichael 12 Special Events 49 Year 12 - 1991 78 Photo by: Z Turner 2 EDllORIAL 1991 has been another lively and exciting year at PLC with continuing growth and achievement in all aspects of School life. The year started on an incredibly high note when PLC finally ended St.Mary·s seven-year reign over the Inter-school Swimming, providing the entire School with a feeling of immense pride. This team success generated a number of outstanding individual achievements in the sporting arena. Michelle Telfer again made us proud with a personal best performance in the World KOOKABURRA COMMITTEE (Year 12) Gymnastics Championships held in the Back (L-R): E Rigg, S Pye, L Price, SKelly, N. Giblett, Z Turner, S Angus. United States, while here at home Centre (L-R): N Low, A Hutchison, T Johns, A Lim. Michelle's sister, Nicola, was selected for Front (L-R): SHeng, K Webb, E Keen, E ewland, A Reddin. the National Championships in the Eastern States. Other outstanding indi 1991 also saw the introduction of rowing We cannot begin to express our apprecia vidual performances came from Elizabeth at PLC. -

14Th FINA WORLD MASTERS CHAMPIONSHIPS

14th FINA WORLD MASTERS CHAMPIONSHIPS 50 m Freestyle Women Results RANK SURNAME & NAME NAT BORN CAT TEAM FINAL AGE GROUP 95-99 CR : -- WR : 1:14.38 1 JOHNSTONE Kath NZL 1917 95-99 North Shore Masters 1:44.61 NOT CLASSIFIED NAGAOKA Mieko JPN 1914 95-99 Ksg Kirara Yanai Sc DNS AGE GROUP 90-94 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 1:41.97 CR : 1:02.28 WR : 54.97 1 KORNFELD Maurine USA 1921 90-94 Mission Viejo Nadadores 58.68 CR 2 FRITZE Ingeborg GER 1921 90-94 Duesseldorf Sc 1898 1:18.25 3 BOHM Barbara GER 1920 90-94 Tsv Siegsdorf 1:37.13 NOT CLASSIFIED GUILLAIS Michele FRA 1921 90-94 Entente Nautique Caennaise DNS AGE GROUP 85-89 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 1:24.15 CR : 48.25 WR : 44.70 1 KOKORINA Olga RUS 1923 85-89 Neva Stars 51.05 2 KAPCAROVA Magdalena SVK 1927 85-89 Pvk Bratislava 52.04 3 GJORES Kerstin SWE 1927 85-89 Simklubben Nautilus 52.22 4 WIDAHL Eva-Britt SWE 1926 85-89 Simklubben Nautilus 54.44 5 GENOULAZ Louisette FRA 1925 85-89 Ems Bron 1:14.23 6 KLOOS Kascha RSA 1925 85-89 Cape Town Masters Sc 1:18.42 NOT CLASSIFIED HALTER Susan GBR 1927 85-89 Camden Swiss Cottage Sc DNS AGE GROUP 80-84 QUALIFYING STANDARD: 1:04.35 CR : 41.96 WR : 38.64 1 ASHER Jane GBR 1931 80-84 Kings Cormorants 38.60 WR 2 SCOTT Nancy GBR 1931 80-84 Caledonia Masters 49.49 3 GRILLI Britt SWE 1928 80-84 Simklubben Nautilus 49.93 4 FEITOSA Sonia BRA 1931 80-84 Clube De Regatas Icarai 52.60 5 GRANE Marianne SWE 1931 80-84 Simklubben Nautilus 55.02 6 GOGGIN Georgia USA 1929 80-84 Masters Of South Texas 56.52 7 MURAYAMA Chieko JPN 1930 80-84 Csc Chiba 1:00.66 8 PARODI Marlene ARG 1932